SGU Episode 840

| This episode needs: proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 840 |

|---|

| August 13th 2021 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

The earth will not continue to offer its harvest, except with faithful stewardship. We cannot say we love the land and then take steps to destroy it for use by future generations. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, August 11th, 2021, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Happy birthday, Jay.

J: Thanks. Thank you.

C: What?

B: Yeah, happy birthday, Jay.

S: Today's the actual day and Jay agreed to do a show on his birthday.

C: Aww.

E: Isn't that nice?

J: I would rather be with my family my kids and everything, but the show, like, Steve, 16 years, we haven't missed a week, right?

S: Definitely we could say now we haven't missed a week in 16 years.

E: Yeah.

J: You know, and at my age, what am I doing on a Wednesday night in the middle of the week like-

S: Yeah, we celebrated already. What do you want, two birthdays?

J: Yeah, we had a party.

E: It's your birth month.

B: It's not like it's your 50th birthday when you had two huge parties in a row.

J: Well, the first party was the decoy party.

E: Oh, yes.

B: What's the best way to surprise somebody? Throw them a fake surprise party. He was so not expecting that second one. He was, like, negatively expecting it. Like, no way we could even imagine that, oh, he's going to have another one that's even better. So let's talk about a surprise.

E: Misdirection.

C: It seems like a lot of work.

B: It was. It was.

J: For just Jay, for me, I could see.

C: I just think I've never had a surprise party. I don't know. It's just it's not, like, part of my culture, I guess. Or, like, big parties on, like, at 20, 30. Well, I guess those are the only ones I've had.

B: I hate you right now.

C: 40's coming. It's coming pretty soon.

E: Yeah, a couple years, right?

B: It's a bad one.

J: I thought the surprise was going to be that she was taking me to play laser tag or something. You know, like, I was like.

C: Ooh, I want to play laser tag. When's the last time you guys played laser tag?

S: I played laser tag.

J: Yeah, we did it a few years ago. It's always fun.

B: It's fun. That's fun.

C: I haven't done it since I was a teenager.

J: Oh, it's a blast.

C: No pun intended. Did you do it out? Was it like an indoor?

S: Indoor. Yeah, the next thing like that I want to do, though, is a VR suite. You know?

J: Yes.

E: Yes.

J: Do you know what that is, Cara?

B: Where is that?

J: You go to a it's a VR studio where you are wearing the VR stuff. You're wireless, right? And what they do is they marry. No, no, it's VR. But they absolutely marry a VR environment to a real environment. So when you reach out and you see a door in front of you, there's actually a door in front of you that you're opening that matches the door in the VR environment.

C: And there's like there's like gravel under your feet. If it looks like there's gravel under your feet, like that kind of stuff. Yeah, that's cool.

J: Yeah. So there's like a Ghostbusters one. And they give you a Ghostbusters type unit that you hold in your hand.

C: That's awesome.

J: So it feels like you're holding the what were those called?

E: Proton accelerators?

B: Unlicensed accelerators. They actually loan you them. That's cool. I'm so going there.

C: Yeah, that sounds really cool, actually. I'd be down.

S: All right. So did you guys see that they announced the two hosts, a new host of Jeopardy?

C: Is it a 10 host or a full time host?

S: Oh, there's a full time host is Michael Richards, who is just a game show host. You know what I mean? That's a good job. And then there's a second host who's going to do specials and other Jeopardy events. And that is, who do you think?

J: LeVar Burton.

S: Nope, no. He was the fan favorite, but they didn't pick him.

C: She is a woman. Yeah. It's a Mayim Bialik.

S: Yep.

E: Yes.

S: Which I thought was an odd choice.

C: It is an odd choice.

S: Yeah.

E: Yeah. It's not well researched, right? I don;t know how else to put it.

C: Was she one of the rotating guest hosts that they tried out? Oh, yeah, she was. And so she must have tested well. I mean, it may seem to us like it's an odd choice, but they have lots of statistics. They have lots of focus groups that they look at.

E: Big Bang Theory was very popular.

C: Yeah.

E: No doubt about it.

C: You know, they put so many people up, so.

S: There's two problems I have. One is she's not an anti-vaxxer, but there were some questionable things in her history, like her kids are not fully vaccinated. And she basically said it's none of your business why that is.

C: Yeah. She's definitely promoted some like supplements.

S: And then that's the second thing. She's basically shilling for Noriva, which is a a brain supplement snake oil. So she's a snake oil salesman. You know, and she's a neuroscientist.

E: Yeah, totally. Degree to that.

S: So, yeah, I'm unhappy with that. I think LaVar would have been a better choice.

B: Yeah.

E: Yes.

S: So but maybe she'll reform her snake oil ways. She did say she did come out and say that she did get the she and her kids are COVID vaccinated.

B: All right.

C: That's good.

S: But then she says stupid things like, but no vaccines, 100%. Yeah, no, no shit. No one came to their 100%. Why do you bother saying that?

B: That's a straw man. That's such a straw man.

S: Is that news to anybody?

E: Tell me what is 100%.

B: Yeah. So what's the implication there? What does that actually mean?

S: I know. Why? Why are you saying that? That's like you could say something that's true. But the fact that you feel like you have to say it is really the thing.

B: It's revealing. It's revealing.

C: Yeah, that's what's telling you. Yeah, exactly. That's like a weird dog whistle. I don't know. There's just something.

S: It's a dog whistle. That's exactly what it is. It's like, I'm not anti-vaxxer. I'm just going to throw a little dog whistle to the anti-vaxxers just to know that a little wink and a nod. Don't worry about it. Yeah, I didn't like it.

B: I think they should have just CG'd me.

S: Alex Trebek, just CG Alex Trebek.

B: Yeah, they got the deep fake audios.

E: Oh, yeah, the deep fake.

C: Yeah, you'd think. I mean, if you think about all the footage they have of Alex Trebek. And the number of words he's spoken over the years, hundreds of thousands, if not millions. All the guests and their names. You guys remember that episode of Black Mirror where they made a boyfriend just out of all of the texts and social media posts and voicemails. They could easily do that with Alex Trebek.

B: I mean, the training they could have done on all that video content would have been realer than real Alex.

J: I think today they only need like three hours. Three hours of video.

S: Here's 30,000 hours of Alex Trebek.

B: Well, I mean, yeah, Jay, I could see a few hours to do a good deep fake, audio deep fake. But with a lot of deep learning training, the more the better.

C: Oh, it'd be flawless. And this is a perfect set up for it.

B: Within reason, of course.

C: You never need him to be next to the guests. He's always in a different frame, too. So it's like even easier.

S: That's true. He's never next to the guests.

B: The thing is, though, here's one weakness. It'd have to be on the fly. That's what would make it maybe extra tough, right?

E: No, it's edited.

C: Well, not really, though. It's they don't they don't retake questions. It's really important that they do everything as live as possible for the guests so that it's fair. Like they have a whole audience production team that keeps it very, very fair for the competitors.

E: I don't see why that'd be a challenge, though, for the computers to deal with that.

B: Well, it's just real time interaction with humans in a way that's I mean, that's a little bit of that's some advanced AI to have to have. It's basically the Turing test, right?

C: Right. But early on, all he'd really have to do is go, that's incorrect. Or you've got it. That's the double.

B: I'll give you that because 90 like 98 percent of the interaction is pretty standard interaction that you could just pull from a database of of things that he could say. That's true. Like someone's like when they tell you their life stories in the beginning, you're like, that's interesting. Next contestant. You know, that's pretty easy.

S: It would be like a video game with bad AI like the same things over and over again that are increasingly out of context to the things that your characters actually do.

B: Right. I wonder if the Alex Trebek estate would agree as much as I love Alex Trebek.

J: As much as I love Alex Trebek, I don't know. I mean, I think I'd rather have a live person there. Give someone else a go. I think LeVar Burton would have been amazing.

C: A lot of people agree. A lot of people agree. But clearly, again, like probably in the grand scheme of things, they chose who they chose based on data. This is a very common way to make decisions in television.

B: Oh, sure.

C: So we may not be representative of the core Jeopardy audience and the core Jeopardy audience may have been like, these are the people we want to see hosting the show. We like them the best.

B: Yeah, that's fine. I'm sure they're going to they didn't just flip a coin. But I think we're going to be seeing digital resurrections of famous actors. That's I mean, they're doing it. They're already done. But it's going to become more and more prevalent. I would like to see them go full hog on Alex Trebek CG totally just like I mean, because he is the iconic Jeopardy guy. I mean, he's this would have been a cool place to do it.

C: Yeah, he is Jeopardy. And really, that's up to their estate. Like, there's a lot of legal implications.

B: Oh, sure. They would have to agree. There's no way they would their his estate. They could do it without his estate. But I think it'd be cool. Just I just want to see it.

S: Bob, is it full hog or whole hog?

B: Oh, what did I say full?

S: Yeah, you did.

B: All right, you know.

C: Get the nail on the button.

S: It kind of loses the alliteration there when you go full hog.

C: At least it means the same.

S: It's full Monty, but it's whole hog.

B: Whole hog. Yeah, absolutely correct. But you know, the hog is the operative word there. You know, the alliteration is great. But hog is such an awesome word. But yeah, you got me.

S: All right. That was my pedantic quote of the day.

B: Yes, that's quite all right. Because I'll do the same to you soon.

S: Sure, go for it.

News Items

IPCC Sixth Report (9:49)

S: Cara, the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, just released their sixth report. So what is the state of climate change in the world today?

C: Yes, not good. And scene. So we know about the IPCC because we cover it each, probably about every seven years. They put out a new report. Of course, this is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And for those of you who don't know who the IPCC is or what the IPCC does, it was actually founded in 1988 by the World Meteorological Organization and also, of course, the United Nations Environmental Program. So it is a United Nations working group. It currently has 195 members. And when I say 195 members, I mean 195 countries.

E: Well, that's most of the planet.

C: Yeah, are part of the IPCC. It's made up of scientists. The scientists get nominated by these countries to be involved in these different reports. This go around, it was 234 scientists. They read over 14,000 research papers to put together this sixth report. And I'm going to cover some of the top line kind of takeaways of the report, but I'll tell you what, none of them are good. So we're just starting off this episode with a big bummer. And hopefully, did any of you do a news item that's happy? Because we're going to need a palate cleanser.

J: Mine's happy.

E: Mine's about scams.

B: Mine's a little disappointing, but fascinating as hell.

S: Yeah, that's mine. Mine fits in the disappointing, but fascinating.

J: Mine will remove fear and tension from your life.

C: Okay, because this is not just a little disappointing. This is horrible.

B: And surprising? So how much of a surprise is it really?

S: I mean, not at all.

C: It's not a surprise at all. And anybody who's been following any of this research knows that this is exactly what was expected.

S: Cara, I will give you a ray of hope at the end there.

B: Oh, yeah.

C: Okay.

B: Awesome.

C: All right, that's good.

S: It's not 100% doom and gloom. Go ahead.

B: Yeah, because we could all just go into VR 100% of the time and ignore the environment.

C: Yeah, this is that, what was it called? The metaverse? This is really going to come in handy.

E: Yeah, metaverse, where are you?

C: So yeah, this isn't a surprise to pretty much anybody who hasn't had their head in the sand. But it might feel and does feel like a gut punch, because it makes it real when it's all laid out on paper.

S: Yeah, it's like 100 climate science news items all at once.

C: Yeah, exactly.

S: But we've been reporting them all along.

C: Absolutely. So let's talk about some of the big takeaways here. The deck this last decade, the last 10 years was hotter than any period in the last 125,000 years. Okay, so this is a big kind of major point to take.

B: Coincidence, you know.

C: Yeah, there's absolutely no way it's a coincidence. We know now that specifically due to human activity, and this is in no uncertain terms, this is unequivocal in the report, specifically due to human activity, greenhouse gases, and we're talking at the top, carbon dioxide and methane, they have elevated the global average temperature by 1.1 degrees Celsius above the 19th century average. Now, we have already done enough that it will hit 1.5 degrees Celsius, no matter what we do.

E: You can slam on the brakes, it will not change.

B: If it disappeared today, basically, this...

C: Yeah, we're gonna hit 1.5, and it could be as early as 2030. Yeah, somewhere between 2030 and 2052, I think. It was kind of a random number in there. And 1.5 was sort of the goal that was hit by the Paris Climate Agreement. So we know we're going to hit that. We know we're going to go over it. We know we are. But we're guaranteed to hit 1.5 degrees Celsius. As I mentioned before, we can unequivocally say this is due to human activity. And when we say this, we mean all of it. We mean the increase in global temperatures. We also mean the extreme weather events. And I think historically, when we've talked about things like hurricanes, when we've talked about things like kind of focal flooding, we've had to hedge a little bit and say, we can't completely link this together. We might say that there aren't more necessarily, but maybe they're getting worse. Or maybe they're not necessarily getting worse, but this one might not have been as likely. But now we can kind of unequivocally say, based on all of the available evidence, that these terrible weather events are directly linked to anthropogenic climate change. Two of the major things that changed is, number one, our computer models have gotten way better, like way better. And most of this is done based on really, really intricate computer modeling. But number two, this report utilized so much more local data than ever before. So we weren't just talking about global averages, or historically, we've often been talking about global averages. But what this report did, which is really, really brilliant, is they looked at individual recordings from buoys in the ocean all over the world, from sensors in different countries that are rich versus poor, places where there are different socioeconomic demographics. And this becomes very important in the modeling, because historically, modeling was based on what we might want to call like physical science metrics, like it was based on things like temperature, humidity, sea level rise, acidification. And now the models are taking things into account, like socioeconomic status, poverty, food insecurity, and they're adding those models together. So it's not just about this is what it's going to look like on the planet, but this is how that's then going to affect people, especially in vulnerable places. And I think that's a really important outcome of this study.

S: Cara, but just to clarify one thing, though, for every specific claim they make in the report, they give a confidence interval, or they—

B: Oh, sweet.

C: They do. I love that.

S: Yeah, so, I mean, you're saying that this is unequivocal or whatever, but that's only for certain aspects of the claim, and that is for like the big ones, like it's happening and we're causing it, right?

B: And we're doomed and all that.

S: Yeah, that's in the virtually certain region.

C: Yeah, and when I say it's happening and we're causing it, what I mean is the temperature is increasing, weather patterns are changing. You know, those are the big ones.

S: Yeah, but for a lot of the effects, so they have—

C: Like a hurricane, specifically.

S: —virtually certain is 99 to 100 percent. Very likely is 90 to 100 percent. Likely is 66 to 100 percent. They also talk about medium confidence or high confidence. So not every subclaim is—

C: No, no, no.

S: -is certain, but they say next to every one, like sea level rise, this is in the high confidence range, and this specific effect is in the medium confidence range. The hurricane thing is actually towards the medium end.

C: But also, are you looking at the modeling claims that say in the future this is what it will look like?

S: Yeah, so there's two things. That's right. So there are claims about today, like this has already happened, and then there's this is what the models say are going to happen.

C: And that's what I was saying is unequivocal. We can now link these severe weather events that have been happening to anthropogenic climate change, when we couldn't really do that before, at least not at the level of confidence that we can. Yes, a lot of the modeling, we have to speak in terms of those confidence intervals.

S: Yeah, but even there, because I read through the whole, not the whole report, it's 1,300 pages, but the whole—

C: Yeah, no, the summary, yeah, yeah, yeah.

S: So for heat waves, it's in the high confidence range. For tropical storms and stuff, it's still in the medium confidence. And the reason there is that the models predict that the intensity will increase, but not necessarily the frequency. So if you look at the number of very intense hurricanes increases, but not the total number of hurricanes. But there's also—

C: Oh, I see what you mean. I see what you mean. Yeah, yeah, yeah. The intensity of the high frequencies. Sorry, the frequencies of the high intensity.

S: But really, just overall intensity is increasing, not necessarily the overall frequency of all hurricanes. This creates a lot of confusion in the discussion about it, I have found. But there's also- And then some reports combine frequency, intensity, and duration into one overall measure. So that is another level of complexity in there. But in any case, there are areas where the confidence is very high, like the fact that the sea levels have risen. The fact that heat waves are happening is a very high level of confidence. The fact that droughts are increasing is a pretty high level of confidence. But yeah, you have to look through the report, and next to each specific claim, it'll tell you.

C: Yeah, they put it in parentheses right after, which is really nice. I mean, I think it's transparent, and it actually really helps those who already understand or have an appreciation for the scientific method. It really helps them make sense of the data. I don't want to say I worry, because I know for a fact. It also gives fuel to deniers, but deniers are going to deny.

S: Totally.

C: And yeah, and the truth is we can't kowtow to that. And I think that's what a lot of the reporting around this that I'm seeing that I'm really excited by is basically saying deniers are going to deny. We don't have time for that anymore. This is undeniable. We've got to just move past it. So, Bob, what I was going to mention is that there's a science news article that kind of summarizes some of the data in a way that's really interesting. And obviously IPCC does this as well, where they basically say, OK, today's temperature is at 1.1 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. We know we're going to hit 1.5, even if we make no changes, based on everything we've already done to this date, because there's a delay effect, right? And then there's modeling at 2 degrees Celsius, which is a very likely outcome. And 4 degrees Celsius, which is still pretty likely if we don't make any changes. 2 degrees Celsius, we hope we can get to that point or lower, and we'll talk about what that would take. 4 degrees could happen, really could happen, especially if we dry our heels. In this little summary, they show really cool things. So, like, right now, droughts. We are twice as likely to have a once-in-a-decade drought right now. But if we go up to 4 degrees Celsius, we are 5.1 times more likely to have a once-in-a-decade drought occurring.

B: Yeah, they got to rename those things, right?

C: Mm-hmm, exactly.

B: No longer once-in-a-decade.

C: Exactly.

B: Once-in-a-century, even.

C: Yeah. So that's when we're talking about, like, frequencies and likelihoods. The idea is that there's sort of a baseline likelihood, and as we increase, those likelihoods also increase, and they're not lockstep. Sometimes they're significantly higher, like snow. We're talking about, right now, there's a 1% less — we have 1% less snow cover than we did in pre-industrial levels. If we get up to 1.5, which we will, we're talking 5% less. If we get up to 2, 9% less. If we get up to 4, 25% less.

E: Oh, boy. We've talked about how that has a terrible impact on the world.

C: Yeah, and they have this knock-on effect that continues and continues, and then it just kind of has this runaway train problem. And some outlets have taken that information and turned it into real numbers, like saying, we can expect a terrible hurricane if it happened once in a decade. Now that means that it might happen once every five years, and now that means it's going to happen once a year and so we can sort of model in that way as well.

B: Yeah, one point I wanted to make is that I remember telling my mom about all of this, and she's like, one degree, two degrees, so what? And I'm like, you know —

C: 'Cause we're used to changing the temperature in our house by one degree and being like, what does that matter?

B: Yeah, so I was trying to tell her that. It's not like, oh, my town is one degree hotter than it was last year. And the point is to recognize that a one degree, one and a half degree uptick for a global average represents so much heat that it's just hard to appreciate how much heat we're talking about to increase the worldwide average by one and a half.

S: It's a lot of energy in the system.

B: So much energy is required to go up 1.5 degrees that it just, it seems like it's hard to think of because it doesn't seem like a lot.

C: Absolutely. Think about how big the world is. How big the world is in all of the buffers that are in effect, all of the ways that nature has been desperately trying to prevent this from happening. And it's still happening past all of those locksteps, past all those natural buffers.

B: Think of your pool. To go up one degree for that, your entire Olympic-sized pool, that's a lot of heat. Now extrapolate that to the planet, to the water.

C: Right, yeah. And so I mentioned, number one, the last decade was hotter than any period in the last 125,000 years. One thing I didn't mention, atmospheric CO2 is higher than it's been in two million years. And combining all of the greenhouse gases, we're talking methane, nitrous oxide, these different gases, at least the last 800,000 years, we're at an all-time high. We now understand better what the range is going to be for how temperatures actually respond to greenhouse gas emissions. We didn't understand it quite to the level that we do now. Basically, what that's saying is that our models have gotten much cleaner and we can make stronger predictions based on outcomes.

S: So that's climate sensitivity, which is essentially, if you double the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere from pre-industrial levels, and where would the climate reach its new homeostasis, right? And how much increase. And so the range used to be between 1.5 and 4.5, and now they narrowed it to 2.5 to 4. But then they're saying it's basically 3. Yeah, it's a pretty sharp bell curve around 3, but the 95% goes from 2.5 to 4. So they essentially cut off the two extremes. But what that means is the best-case scenario is a lot worse now than it was when... Because the climate change minimalists or deniers could say, well, it's possible that the climate sensitivity is only 1.5, and then that's not going to be that bad. But now, even in the best-case scenario, it's 2.5 degrees C, and that is still very, very bad.

C: Right. And let's talk about that best-case scenario, because one thing that's important to remember here, and maybe will give us a little bit of hope, is that the minute we stop with global emissions, if we halted them, or even if we decrease them below a threshold, heating will stop. Temperatures will stabilize. Some things aren't going to change. Sea level rise, it's going to continue. But because there is that knockoff runaway effect, right, of especially the ice, the large ice sheets breaking up, and a lot of the changes that come from that. But if we were to completely stop overnight all global emissions, we would halt this rise in temperatures. And so it's really, really about our behavior. And we have the power to make changes, but governments have to act.

S: So, yeah, I mean, I think those are the main takeaways, Cara, but just my slight ray of sunshine gets to the, they basically said, here are five scenarios for how, what could happen between now and 2100, from we are fantastic, and we do everything we're supposed to, and we're net zero by 2050, basically, and versus we do nothing, and there's just a continued linear increase in CO2 release, and then everything in between. The good news is it's not technically too late to stop warming at 1.5 C, if in the best case of those five scenarios. But unfortunately, I think it's extremely unlikely that we're going to achieve that, personally. I don't think we have the political will.

C: Yeah, I think the 1.5 is impossible.

S: Yeah, we have to hope for somewhere in the middle, which is where I think it's going to happen, and hope that we don't get the worst case scenario. I mean, I think it would require a massive policy shift for China and India, first of all, let alone the United States.

C: Yeah, I mean, right there. Yeah, let alone the United States.

S: The three big emitters. We all would need to do that, and that's just not on the cards. I mean, China just has no plans on doing that right now. It would require a massive policy shift.

C: And even all of our policy that we have spoken, you know, it's crazy, because what you do is you hear our own politician saying, the world must act, we must act, and then when you look at our own policy, it's not enough.

S: Yeah, that's the thing. Even with like Democrat in the White House, and basically the, let's do everything we can about global warming party in power, their plans are not going to do it. They're not going to do it. They're not going to hold the warming to 1.5 C, or even are part of it, even the United States piece of that puzzle.

C: Yeah, it's not fast enough.

S: It's just not fast enough. It's just not fast enough. So I think it's going to be two. It's going to be two degrees Celsius. We just better hope that that's it because it could be worse than that.

C: It could be worse. And I think the thing that we have to kind of, one of the takeaways that I've seen a lot of really good, like the New York Times did a really good right around all about the IPCC report. They talk about what the report says. They talk about the global reaction to the report, and then they do like a deep dive into what's going on in the ocean. And I really appreciated their reporting on the global reaction, kind of because we tend to get stuck in our Western bubble. We especially get stuck in our American bubble. And one of the things that I think we have to come to terms with is the fact that here in America, and you're right, Steve, along with China, India is in the top, but it's more that it's on deck to be one of the bigger producers.

S: It's because of their population.

C: Yeah, I have a list of the top 10 kind of worst offenders, but it's definitely America. China's number one. America comes soon after. The European Union is up there. Canada's like number 10. So in between there, you've got, I think, Indonesia. You've got Brazil is in there somewhere. And so, but really, China and America are like right there at the top. And yes, we have set targets and goals, and yes, we are working to accomplish them, but they're not, A, they're not good enough, and B, what they don't take into account is the fact that what many poorer nations are basically angry about is that we have used up our portion of the climate budget.

S: Yeah, we've used up the carbon, it's done. We've basically used up the carbon budget.

C: The carbon budget, thank you. And the sad thing is, this is like the really unjust part of the global climate system, is that the worst offenders don't feel the effects as much. So we see that the poorest countries, and especially the island countries that are only, however many feet above sea level, are dealing with the worst effects. And when we talk about not just the global climate budget, or sorry, carbon budget, meaning how much carbon we're putting in the atmosphere, but if we actually kind of translate this into dollars and cents, unfortunately, the rich countries aren't doing enough to help the poor countries. We're very often saying you're on your own.

S: So here's another, if you look at it a certain way, it's a positive thing, it's a ray of hope.

C: Ha! Yes, please enlighten me.

S: And that is that all of the things that we should be doing are actually worthwhile investments that will pay off in the long run. It's actually in our best economic interest. Like, even if you say, like, if we invest money in developing nations, developing renewable green energy, we will benefit financially from that, if you're looking at across a 50 to 100 year time span. But that's the problem. It's really hard to look at that. But we really need to. If any dollar we invest in mitigating climate change, we will get back 10 or 100-fold in savings.

C: Absolutely.

E: The problem is there's no immediate political capital to do so, so there's no will.

C: Well, when it becomes an existential threat, where at what point do we stop being so glib and cynical, right? So when it becomes an — well, it already is to some extent, that's really the problem. People love to talk about tipping points. I think it's a vague term, and it's a little bit unfortunate a term, because I think it can be misused and misunderstood. But we are at a crossroads, at the very least, where some stuff isn't going to get better. Other things could get way better, but we don't have policies in place to allow that yet. So it's like we already missed the final exam, and now we're begging the teacher to let us do a retest, right? But we didn't study. Yeah, we didn't study. And so we're making up lost time here. And it's really unfortunate because who ends up suffering are the inhabitants of the Marshall Islands, the inhabitants of Bangladesh, the inhabitants of Pakistan, the inhabitants of places in the world where the temperature is unbearably high. In Pakistan, I think that the high temperature was — or the average high, something like that, was like 122 over the summer, something insane. And we're talking people being flooded out of their homes. And what is going to be a direct effect of that?

S: Climate refugees.

E: Oh, refugees.

B: Millions of them.

C: Millions of displaced people.

B: It's too hot to live back home.

C: And it's one of these problems that we see over and over, and the conventional wisdom is so incredibly beneficial. We know that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. We know this. And unfortunately, we're talking about the worst possible cancer, where at a certain point, if we don't prevent it, there is no cure. And I think that's how we have to look at this problem.

S: Yeah, I think just politically, just overall, we need to make a clear distinction between spending money and investing money. And you can't look at an investment as if you're throwing that money away or you're spending it. And it should not be thought of. And even economists will tell you, like even going into debt, debt is not a problem if you're spending the money on investments that will pay off in the future. Like I say, even like buying electric vehicles as an investment, a little bit more money up front, but you actually save money on the life of the car. So there's a lot of things like that where, yeah, we need to, yeah, I think we should invest in Gen 4 nuclear. I think we need to upgrade the grid and we need to push renewables and we need to incentivize EVs and we need to do all of these things, everything, and then maybe we can squeak under the wire. But we're not, we're near close to doing everything. But all of these things are actually cost effective if you count the long term.

C: And here's the thing. They're possible.

S: They're possible, yeah.

C: Yes, this is a zero sum game. There is only so much money, but we have enough. It's all about where our priorities lie.

S: And we have, the science is already here. We don't need any breakthrough. It's only going to get better. The science is only going to get better. But even if it stood still, we still, it would still be fine.

C: No, we're like, we're like those people who are, show up to the doctor and they say, we're dealing with this thing. It's definitely something that we can beat. We have the medicine available. We've just got to go step one, step two, step three. Are you in? And then we're going, I don't know. Yeah, I think I want a 19th opinion.

B: Yeah, I predict that the globe won't act as they should be acting with urgency and commitment until we decide that four degrees or higher is already inevitable. Then we might say globally, oh boy, we really got to take this seriously. That's what it's going to take.

C: Yeah. I hope that that's not the case because I think that, I think that we are feeling the effects more and more. And I think that we are at least in this country, like you said before, Steve, we at least are dealing with a government right now that's attempting to prioritize these things. And I'm really hoping that this IPCC report, this number six report is a massive wake up call. Remember, this just came out as of this recording two days ago. My hope is that it really does light a fire.

S: Yes. A metaphorical fire is inferiority.

C: Yeah, exactly.

S: All right.

Yellowstone Myths (34:25)

S: Jay, tell us about Yellowstone myths.

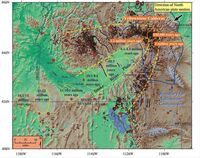

J: All right. So I'm sure many of you have heard that Yellowstone National Park, which is located mostly in the state of Wyoming, is sitting on top of one of the world's largest volcanoes.

E: Oh, a super volcano out there, right? Yeah.

B: Oh, God damn it.

E: That's what I've heard.

J: Cara, what do you think?

C: Myth?

J: Are you scared? Does this keep you up at night in any way?

C: Not at all.

J: So in fact, the park itself is mostly in something called the caldera. So if you don't know, a caldera is the crater that's left after a volcanic eruption. So this means the park is mostly located in the actual mouth of an old volcano.

S: Jay, isn't there a caldera complex? Like it's multiple calderas?

J: Yeah. Well, in this instance with Yellowstone, yes, I'll get into that. There's been multiple calderas over a very long period of time.

B: And they're huge.

J: The geologic history of the park is really amazing. So about 16.5 million years ago, a plume of magma created a series of volcanoes. This is similar to the way that the Hawaiian Islands were formed, right? So you know that as the tectonic plates move across that magma plume, it just creates another landmass and another landmass. So North America is moving over a magma plume, right? And every once in a while in geologic years, there is some volcanic activity that creates, that changes the landmass and spews lava out onto the crust, right? So if you look at a map of the United States, the plume erupted. Now, this particular plume that we're talking about that is now underneath Yellowstone Park initially erupted 16.5 million years ago in the area that we now call Oregon. And then it moved on to Nevada, Idaho, Utah, and then into Wyoming where it is right now. Now, this series of eruptions occurred over a 750-kilometer spread. And that took 16.5 million years. So about 2.1 million years ago, the magma plume reached where the Yellowstone Park is right now. So that's when the North America tectonic plate moved. And now the magma plume is underneath where the park is. And at that time, the plume was ready to erupt. And it ended up being one of the biggest eruptions in geologic history. Now, that eruption sent ash and debris as far as Mississippi. Now, to get a sense of how far that is, I know everyone doesn't know the United States as well as the next person. To get a sense, Mississippi is almost touching Florida. And that's about half the width of the country. So if you just imagine the panhandle of Florida, Mississippi is just a little bit to the left of that. And now go halfway across the country, and that's where the volcano was. That's a huge distance. Geologists say that compared to Mount St. Helens, it was 6,000 times worse.

E: Whoa, 6,000 times Mount St. Helens.

J: Yes. So since then, there have been three more eruptions. So 1.3 million years ago, we had an eruption. 630,000 years ago, we had another big eruption. And then 70,000 years ago, we had lava flow. So of course, all of these events changed the landscape into what it is today, which in a weird way have, in a sense, fashioned the park. So Native American people lived in this region going back 11,000 years. And the park was founded in 1872. So of course, Native American people have been there much longer than anybody that came here as a United States citizen. Unfortunately, one of Yellowstone's superintendents spread a myth about how the Native people were afraid of the park's land due to the volcanic thermal areas, right? So you have the hot springs and geysers and all sorts of things like that happening. And this guy is telling people that the Native people are super scared of it. And that was a lie because the Native people considered the area to be sacred. And they highly respected the place. And they did a lot of things there. It was a trading station. It was like so many things to a lot of people going back 11,000 years. And I recommend that you take a look at this. Read more about the Native American history in that area. I guarantee you, you'll find it very interesting. But that's not what this news item is about. These myths may have led to some of the modern fears, however, of the giant volcanic eruption, right? You know, all the stuff that we've heard since we were kids. It's commonly called a super volcano. And you know, it's funny. I'm happy that one of you guys said it. Evan, you said it. I used to say it all the time up until about three hours ago. But that is not a scientific definition. And you know, I didn't know. And calling it a super volcano propagates this unjustified fear. So just an FYI here, geoscientists refer to the area as Yellowstone Caldera System or Yellowstone Caldera Complex. And the fact is Yellowstone... Now, Cara, I want you to be happy because you had a really negative news item.

C: Yes, please.

J: Yellowstone is not due for an eruption.

C: Thank you.

J: Volcanoes simply don't operate on a schedule, right? There is no... It's due. That doesn't happen in geology. In the last 2.2 million years, there have been three catastrophic eruptions. There have also been many small lava flows. Geologists say that Yellowstone is not going to erupt any time in the near future. And when it finally does have activity, it will probably be a localized lava flow and nothing explosive.

B: Really?

J: Yes. The last extreme eruption that took place, like I said before, was 630,000 years ago. Volcano eruption intensity is measured using the Volcanic Explosivity Index, VEI.

C: Oh, I love that.

J: I love it too.

J: Now, using that index... And what that determines is how big of an area is the volcano's effect going to be. Now, when we use that index, it's a 0 to 8. When we're talking about the 630,000-year-ago volcano eruption, that was an 8. That was massive. But it wasn't... I heard things... Bob, I remember talking to you about this. I heard them like, lava will shoot up thousands of feet into the atmosphere, and there'll be a wall of lava going across the country. I mean, I was scared to death as a kid.

B: Well, yeah, I remember talking to you about that, but that wasn't for the so-called supervolcano. That's a flood basalt volcano, which is a completely different beast, and you should be extremely afraid of anything like that. That's not Yellowstone.

J: That's not Yellowstone. But I think, Bob, that as the years go by and people add to the story, more misinformation gets added onto it, it's become very much an American folklore, like this volcano is sitting there, and when it goes, we're all done. That's the basic sentiment with a lot of people, I'm sure, around the world, but definitely in the United States.

B: Okay, my understanding, tell me if this... My understanding is this, of that kind of caldera complex, is that when it goes, if it went bad, if you're nearby, if you're within, if you're in that state, you're really screwed. You're toast. The farther away you get, the less and less of the volcanic ash that will come down on you, which is bad stuff, because that goes on your roof, and then it gets wet. I mean, buildings will collapse, but the farther away you get, you're not going to be breathing in that nasty stuff, if you're on the East Coast, but globally, it's going to cover, blot out the sun. I mean, that's going to be bad.

J: You're right, Bob. It's not like, oh, the volcano erupted, it was bad, and we go back to normal. It could potentially have an effect on climate and everything. So there will be volcanic activity when enough magma and pressure are built up underneath the surface. This goes for every volcano. The good news is that neither of these things are happening right now in Yellowstone. So remember I said, there's got to be enough magma and pressure at the same time in order for a volcano to emerge. The two magma chambers that are under the park right now are largely stagnant, and that means that not much is happening. So experts say that if a large explosive event were percolating below the surface, we would know years in advance. There won't be any surprises, guys. There are two magma reservoirs that are only 5% to 15% filled with molten material. That number would have to get to 50% in order for it to even start moving to the surface. So when the magma chambers start to fill up, a lot of things happen that the experts would easily detect. This isn't like it can happen and we won't know about it. We would be like, hey, we're picking up seismic activity. The ground would change shape. There'd be way more heat and gas emissions. These are some of the early signs that can happen. These early signs can happen for decades or even centuries before an eruption. So none of that's happening. So we know at the very, very, very least that it would take decades once we see all of that crazy activity happening before anything would happen. So look at decades to centuries. That's a very long time. They're not even saying it's going to happen in decades to centuries. I'm just saying that that's how long it would take once you start to see these early signs. So Yellowstone is one of the best monitored areas in the world. So let's formally put any fears that you may have about Yellowstone to bed right now. Anybody out there that has ever thought about it and been a little scared about the stories you hear, it's all BS. Even a profoundly strong earthquake would not affect the volcanic activity there. But there is one thing that could happen. If anything is going to happen in the park, it'll be a hydrothermal explosion. This is very different than anything volcanic. As the groundwater moves around, as the groundwater moves around through the hot springs and the geysers in the park, the minerals in the water can build up and clog one of these underground passageways. So that means that once a clog happens, pressure can build up and cause an explosion. Now, these events happen annually. And if they were to happen in the part of the park where people are, it could be very dangerous. But that's just for people in the park. It's not like-

E: Not cataclysmic on a global scale or anything like that.

J: No, because Evan, they happen every year. It's just not around where the people are, luckily. And I guess, again, that could happen. I have no idea. And I looked it up. And I don't know if they have any way of predicting when that's going to happen, because this is like a much more surface thing that's happening. There's not like- I don't think it has much to do with the indicators of when a volcano is about to form. But even still, even with that happening at the park, there's very low probability and chance of you getting hurt with that. So there is nothing to fear here. It's all smoke and mirrors.

Going to Mars (45:05)

S: So I'm going to talk about something that I learned at NECSS. I had the opportunity to ask questions, Jay and I did, of the two NASA speakers that we had. And one in particular, Julie Robinson, was talking about NASA's plans on sending people to Mars, which is something that we've talked about before. So there was some added information that we haven't mentioned before on the show that we specifically asked her about. Like, so what about this? And the answer was a little disappointing, but very interesting. So yeah, one was about shielding, right? Because we've been talking for years about the fact that this is probably he single most challenging technological hurdle to getting people to Mars, is adequately shielding them from radiation outside of the protective bubble of the Earth's atmosphere and magnetic field. And this is all about time. Like how much time you're going to be in space and how adequate is the shielding? What I didn't realize is that I was really, when I was thinking about and reading about shielding, really it was mostly dealing with the solar radiation and not the far more energetic galactic cosmic rays.

B: Yes.

S: Yeah. So when you're talking about solar, so those are the two types of radiation that we need to deal with. The solar radiation are energetic ionized particles, but they could be blocked by a foot of water. Water is actually a very good shielding against that type of radiation. That's largely what they use on the ISS, for example, or the equivalent, the so-called poop shield. If you want to store human waste in the outer hull, there's lots of ways that you could block out that level of radiation.

B: Avenue 5.

S: And yeah, from Avenue 5, and you're fine. But what I didn't realize is that we really have no idea how to deal with cosmic rays. So while solar radiation, the risk there is that it's very variable and it could come in a storm, right? You can get like a massive downpouring. But then hopefully you'd have enough warning to get into some highly shielded part of your moon base alpha or your orbiting station, or even your spaceship. You just get into your little lead blind cocoon or whatever and you're good. But cosmic rays are like a constant steady rain. There's no storm where you're gonna get overwhelmed with it. But these are much more energetic particles. They are powerful enough to cause their so-called ionizing radiation. They can break DNA bonds. They can cause cell damage. And if you get exposed to enough of them over months and years, it can cause permanent damage to your health. Increase your risk of cancer, cause tissue damage, et cetera. So how do you shield against them? So the disappointing part-

E: Just bring a magnetic field with you along the shield.

S: No, the answer was we can't. That was the bottom line. There really isn't anything on the drawing board. There's no defense. So you think, oh, what about just a couple inches of lead? Let's say, for example, would that do it? So she told an interesting story about the Apollo missions where they did that. They actually sealed their film in a lead canister thinking, this will do it. This will block the cosmic radiation from exposing the film. And when they looked at the film back on Earth, it was completely exposed.

E: Oops, that ain't gonna do it.

S: Even worse than you would think if it were unshielded.

B: Right, it made it worse.

S: The shielding made it worse.

C: Did it really make it worse? Or was just the radiation worse than they expected?

S: No, it made it worse.

C: How is that possible?

S: I'll tell you how it's possible.

E: It captured inside and it bounced all around?

S: Exactly. Imagine if I shoot you in the head with a calibre of bullet that will go through the skull and then be slowed down so it can't exit the skull. And it just bounces around inside your skull and makes mush out of your brain, right? That's worse than if it went straight through.

B: That's a great zombie bullet. Awesome zombie bullet.

S: That's basically what the lead did. It was cosmic particles would be able to occasionally get inside and they would lose just enough energy that they couldn't get outside. But they were still really energetic and they would go bouncing around inside the container, completely overexposing the film, right? So yeah, so the shielding that we have the capability of having would only make it worse. You're better off just letting it go straight through rather than risking bouncing it around. And the amount of shielding that we would need to stop it would be way more massive than we could put on a ship. On a base station, sure, you go underground, right? And you're good. You know, you go into one of those lava tubes or whatever, or you build a few feet of regocrete, out of the moon surface. And that's the outside of your moon base. There you go. And even in a station you could just keep putting on shielding and shielding because you don't have to go anywhere, right? But on a ship, like a Mars transit vehicle, there's a strict weight limit that you're going to end up with. And so we just basically could not put enough shielding. So I asked, well, then what's the solution? The solution is you get there faster and we need to research medical treatments that mitigate the biological harm of radiation.

B: Nice solution, nice solution.

C: What can we do to protect our biology?

B: So disappointed.

E: Absorb the hits and take and repair.

C: But what about also like, we're not only concerned about our health and our wellness, we're also concerned about like electronics. We're concerned about other things that are affected by radiation.

S: Yeah, yep.

C: Yeah.

E: Is it our magnetic field on Earth that mostly protects us from these things otherwise?

S: No, it's actually the atmosphere. So the magnetic field protects us from the solar rays because it's ionized.

E: Only the solar.

S: The cosmic rays will, on their way in, they're just likely to hit an air molecule. And then here's the other thing. Here's the other thing. You get daughter particle radiation. So if you use the wrong kind of shielding, you're actually going to magnify the radiation by generating a bunch of daughter particles. Yeah, so you don't want that either. But the problem is if a three-year mission to Mars, we'd be pushing the limits of radiation exposure for the crew. And I think for me, what this means is, even though NASA's like, yeah, we hope to get people to Mars in the 2030s. And I was thinking, no, that's just not going to happen. Honestly, if that's the case with the shielding-

'E: Robots.

S: -well, that's a side point. But assuming our goal is to get people boots on Mars, I think we're going to need nuclear thermal propulsion before we can do it. We need to cut the journey time to Mars in half.

E: And that right now will offer the fastest possible technological...

S: Well, that's the next step.

B: Yeah, that's the next step. And we're heading there. There's been a lot of money being poured into that research. And we're definitely heading there. Finally, I could see the light at the end of the tunnel. But will that even be fast enough, Steve? There's still going to be some good exposure.

S: But here's the other thing very, very quickly was I asked about. So she said, yeah, so on the mission to Mars and back, it would be all in microgravity. Once the ship accelerates up to speed, and then for essentially the entire journey, you're going to be in microgravity. And so I thought, okay, I understand that that's the easiest way to do it. But how hard would it be to throw in a little bit of rotation there and get some artificial gravity going? And her answer was, yeah, no, that's not going to happen.

B: Yeah, you watch too many movies.

S: Yeah, exactly. She literally said that, you watch too many movies.

B: Oh, really?

S: Yeah, she said, I know people think with movies that all you got to do is spin the thing. But she said, but in reality, she did. It would have to be so big, like kilometers in diameter, that we can't build a ship that big. And anything smaller, like ship size, if you tried to spin any part of a ship, it would cause way too much vertigo. And also, you couldn't turn around. You couldn't change your orientation with respect-

C: You're just always going in one direction.

S: Yeah, literally.

B: Because your head would be moving too fast compared to your feet, right? Because the diameter wasn't big enough. So yeah, very uncomfortable.

S: But also, changing your head's orientation with respect to the axis of spin would cause massive vertigo.

C: Everybody's just like passing out and barfing.

S: Hey, I went on that Disney ride, the flight to Mars Disney ride, where they used rotation.

C: Me too.

S: I got vertigo.

C: I felt like I was going to lose consciousness.

J: Steve couldn't even handle the ride.

S: I couldn't handle the ride. For what was it? 20 seconds, I was done, let alone a trip to Mars.

C: Some people died on that ride.

B: Steve, you were puking. You were puking on a big cruise ship when you were six years old. You were clearly not designed to be an astronaut, just saying.

S: Not if rotation's going to be like that. All right, but the other thing is, she said that also, it's a massive engineering challenge. And further, you would have to basically rig the ship so that every piece of equipment operates perfectly well in zero G and under rotation, as opposed to just under zero G. And so the probability of failure goes way up. So bottom line is, it's not going to happen anytime soon for transit vehicles because the engineering risks are way too high and the ships are just not at the right scale. And so we're zero G, microgravity, to Mars and back for the foreseeable future.

C: I think our best bet is just older people who don't mind getting pummeled by radiation. Honestly, I mean, I hate to say that, but people are willing to take the risk.

S: Don't send kids.

B: Yeah, like older astronauts. Like, all right, I live my life.

S: Yeah, but you're right, babe. It's like, this will increase your cancer risk over the next 30 to 50 years. If you're 60, it's like, eh.

C: Exactly.

S: As opposed to 20 or 30, but right.

E: So do these problems also translate to the moon? I guess not. I understand that the distance is not nearly as far, but if you're going to have a base on the moon, there's no atmosphere there. So how are you going to contend with the cosmic radiation?

C: Lava tube.

S: Yeah, you got to be underground. Although she was harshing on lava tubes as well. It's like, it's really sharp down there.

B: She was wrong. She was just wrong. Sorry.

S: You would need to do major construction. But yeah, I think that's...

C: Of course.

S: You're going to have to be underground, whether it's lava tubes or some other thing. You're going to need feet of ground between you and cosmic rays. That's the bottom line.

B: It's so much better, Steve. Let me geek out on that a little bit. It's so much better in the lava tube. I mean, first off, you don't have the what? 400 degree temperature swings, from 200 above to 200 below, right? And there's no micro meteoroids that are going to devastate your environment. And the radiation is horrific. All of this is alleviated by being underground. And also, how about this? Something I read today. I never even heard of this. Do you know when a lander lands on the moon, there's no wind, there's very little gravity. The propulsion, the exhaust from the lander spews out the regolith that can go for miles and even around the moon. So not only are you dealing with everything I just mentioned, but you're also dealing with this high-speed, particulate regolith that could damage equipment and spacesuits. So even that's going to be a problem. You got to go underground. Or if you're on the surface, you're going to have to be buried to a certain extent. I mean, sure, it might be more expensive, but I'm surprised, very disappointed and surprised that she said, yeah, it's kind of craggy down there. Really? That's the big problem? I mean-

J: Bob, why don't we build a space elevator on the moon?

B: That is actually much more feasible than one on the earth. We could much more reasonably do that on the moon than on the earth, for sure.

E: You got to admit it's less romantic thinking about having to live in the tunnels or the holes of the moon rather than the surface.

S: Got to be underground, no question.

Spacesuit Delay (57:27)

S: All right, Bob, we have another disappointing space news item.

C: Oh, gosh.

B: Yeah, it was recently revealed that as unrealistic as the 2024 Artemis moon mission date is, it just got even more unrealistic as it's announced that the Artemis spacesuits cannot be ready for 2024. Just flat out can't be ready. Won't be ready. So yeah, we're all aware now of the Artemis moon mission. I found a great overview of what it is on the nasa.gov website. They say during the Artemis program, NASA will land the first woman and first person of colour on the moon. Yay, that's awesome. Using innovative technologies to explore more of the lunar surface than ever before, we will collaborate with our commercial and international partners and establish sustainable exploration for the first time. Then we will use what we learn on and around the moon to take the next giant leap, sending astronauts to Mars. Okay, sounds good. Sounds exciting. But the biggest problem with the Artemis moon mission, for me anyway, has always been the date for boots on the ground, right? 2024 just was like unrealistically silly. Right from the first time you even heard the date, you're like, whoa, 2024, not gonna happen. You know, it's like a punchline almost.

C: Yeah, but kind of why we've done it before and we did it with like way less time up front on like crappier computers.

E: We had a nuclear race to sort of help propel it.

C: But still, I mean, we had more motivation, but the outcome was that we could do it and we did it fast. It wasn't safe.

B: For what they were planning for Artemis, 2024 just never seemed realistic to me.

C: Okay, so what were they planning? Not just boots on the ground?

B: No, no, no, they said it's not like, yeah, step on the ground. Okay, we're going back home now. No, there's a lot of stuff, a lot of stuff that they wanted to do.

C: Camping?

B: There's camping lava tubes, spelunking, all that awesome stuff. So, but regarding the spacesuit angle though, specifically about the development of the spacesuit, that's what I'm going to focus on obviously. So the NASA Office of Inspector General audited and wrote a report about the status of these new spacesuits. And in the audit, they say, giving these anticipated delays in spacesuit development, a lunar landing in late 2024 as NASA currently plans is not feasible. They also say that NASA's on track to spend more than $1 billion on spacesuit development, just spacesuit development, $1 billion. And by the time the first two suits are ready, which would be April 2025 at the earliest. And I think, my guess is that even that's optimistic. So, all right, so why the delay in the spacesuits? You know, if you think about it, and I'm going to mention the top reasons for these delays, they're really not that hard to predict. And one is the funding shortfalls. That happens all the time. NASA dropped what they planned $209 million budget. They dropped it by $59 million. And they did that because Congress only doled out to NASA 77% of what they requested for the spacesuit program. So that set them back three months right there. And then of course, is the closures due to COVID-19 pandemic. Hello, of course, they had intermittent closures all throughout. That added three months of delay as well. And then of course, there were technical challenges. This is not easy. You know, lots of things could go wrong. They have production issues with their display and control unit, which is what the astronauts are going to use to control the suits critical functions. Circuit boards had to be had to be reworked on. So all that added even more delays. So now despite that, they had a 12 month buffer already added in to the 2024 bud line that they threw in. Let's throw in 12 months buffer just in case. And so even that wasn't enough. They should have made it a bigger buffer apparently. Now, a lot of people have a similar reaction when they say that we have spent or NASA has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on new spacesuits. And they've been working on new spacesuits, I think since 2007 is when they really started working on it. And people will say something along the lines of, I don't get it. We had spacesuits in the frigging 60s and 70s. Let's just make them again. We still have all the designs and schematics. It worked on the moon. Let's just do it again. And that might seem kind of reasonable. Like, yeah, why not? But consider the following. The Apollo spacesuits were not meant for long duration missions. Now you read stories about these spacesuits. They come back to earth. The spacesuits are torn. They're filled with grit. And this is just after three days of moonwalks and like something like on the order of 21 hours and that's it, they're done. And that's mainly because the regolith is brutal. It's essentially powdered glass that clings to everything. And so if you imagine, you've got all these shards of rocks all over the place, making up the regolith and there's no water and there's no air to erode all those little knives that are all over the place.

S: You know what, Bob?

B: They keep an edge forever. What?

S: I hate regolith. It gets everywhere. It's really annoying. It's irritating.

B: Yes, very good. Very good throw out there to that punk from Star Wars. So if you didn't do it, Steve, I would have done it later. So bravo to you. So all those little micro cuts on spacesuits, they add up and they take their toll on those old suits. Most of them or many of them literally would not have survived one more moonwalk. That was it. They were done. But that's okay because they did their job. It was a three-day mission. But Artemis spacesuits, they need to work for not three days missions. They need to work for weeks or months or longer. So clearly the Apollo spacesuits are not, are not anything that you want to design them after. Secondly, we may have the designs for the old Apollo spacesuits, but so what? We don't have the materials. We don't have the technology. We don't have the expertise. We don't have the companies that, because they've gone belly up. You know, they don't last forever. Some of those companies are gone. So we don't have any of that for a lot of these critical Apollo spacesuit components. And that's something that you can generalize to almost any technology. You could ask the question, why don't we just rebuild the Saturn V rocket? Same thing. We just don't have, we don't have all the critical things that we would need to make Saturn V. We could not make the Saturn V today because all those supply lines and materials and technology, the expertise, it's just not there. You'd have to recreate them and rebuild them. So it's just not going to happen. It's not easy that that's why the army, the United States army will have, they'll keep a tank construction company in business. We have plenty of tanks. We've got plenty of spare parts, but the army will continue to make orders so that the technology and the expertise stays fresh in case they really do, really do need them. So they'll kind of like support these companies that we don't really need right now, but we may need. And you don't want that technology to disappear. Otherwise you'll never be able to make the stuff that you want to make. Okay.

S: There's an important generalized point there, Bob.

B: Yes, I just made it.

S: There is- I just wanted to generalize it. There is institutional memory. There's institutional memory. And that goes away if the institution goes away. And it's not easily recreated. It's not like, oh, but it's written down somewhere. It's like, no, no, it's not good enough.

E: You're trying to build a space shuttle.

S: You need the people with the actual experience.

B: Right.

S: And yeah, when that goes away, you have to recreate it. It's gone.

B: Yeah, it really is. And then the last reason, the final reason I have for why we just don't want those Apollo spacesuits is because, of course, the technology. We have better communications, computers, life support. Nobody wants to recreate that old Apollo tech for any of the new spacesuits. We've got to use the new technology.

C: Can you imagine like the headsets are coming in on like old kind of like, what are they like nine pin connectors?

B: Oh, yeah. Right.

C: There's like a tape deck in there.

B: So you might say now that, okay, what about the astronauts in the International Space Station, they've got spacesuits. Right. And that's true. They have more modern spacesuits, but not that much more modern. I mean, they're still they're still pretty old. Some one source said they were decades old. So they're not they're not new either. And also they're designed. Think about this. They're designed for zero gravity near a space station. They're not designed for a zero gravity. Well, they're not designed for the moon. So you really can't even walk in those spacesuits. They're not designed for walking on the moon. You would not want to walk in those. They're way too restricting. You know, they're meant for like floating outside and not walking for sure.

C: Oh you can't walk in them. I wear a spacesuit once for a TV show. It was a mock up. It was like a model of a new one, but it was meant for the space station. And I could take a few steps in it, but they had me get down and like try to do push ups. And then I couldn't stand back up in it because it's basically an inflated bag around your body. Like you've got physical, like I was trying to do stuff with my hands, but the gloves are inflated. And so you have such limited range of motion.

B: Oh, yeah. Yeah, the range of motion is horrible. There's also this problem. How about this one? If you want a spacesuit to fit different size people, then you're just not going to get it because they are not meant to fit a broad range of people. Basically they have very limited options when it comes to that. So do you guys remember how long ago was it? Not too long ago when they tried to have an all woman spacewalk on the ISS, they postponed it. Why? Because the spacesuit sizes, as well as the availability was just not there. And that's just so embarrassing. So how about what is this new suit then? What are they going to do to solve all of these problems? The new suit is called the Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit, or XEMU, X-E-M-U. think that's how it's pronounced, but I like it. I'm going to stick with XEMU. So recently NASA showed it off. They showed off a prototype to show how flexible it was. And you could twist and you could bend at the waist, which suits in the past could not do. It's like bending at the waist? No, you can't really do that. The legs, the suit's legs are pliable. They're meant to be comfortably worn and walked in on the moon. So they're definitely far better than anything on the ISS. And it's all about mobility. I think one of the key things about this new suit, the XEMU, is the mobility. It's got full rotation of the arm from the shoulder to the wrist. They've got special joint bearings so that you can bend and rotate at the hips. Let's see, there's increased bending at the knees. I mean, it's really all about giving you as much mobility as possible. And when you get a suit, they 3D map your body so that they can design, so that they can give you the best pieces to put together for a suit that's maximally comfortable for you and gives you maximal mobility. And yes, it will fit most humans. Amy Ross, a spacesuit designer at NASA, said that we can fit anywhere from the first percentile female to the 99th percentile male. So they can fit pretty much anybody into this new design. And about the regolith. What about the regolith? Because that was getting everywhere, destroying the old Apollo suits. XEMU won't have any zippers or cables. And all of its main components will be sealed within the suit. So the dust knives on the moon can't get in and wreak havoc. So they took that. And of course, it's going to protect you from extreme temperatures from 250 plus and 250 minus Fahrenheit. Huge, huge range of temperature. My God, 500 degrees. And this one was really cool. It's going to be modular. So it's going to have basically a common core system that will be for any environment. But depending on where you are, are you on the space station? Are you on the moon? Or are you on, how about Mars? It will give you different outer systems, outer components to be optimized for wherever you are, whether it has a gravity or no gravity, or even a different atmosphere like the Mars. It will be able to handle the different atmosphere that you find on Mars and the no atmosphere on the moon, obviously. And here's the last one that really surprised me. It's going to have a rear hatch. A rear hatch so you can climb in from the back of the suit.

C: I thought you were going to say so you can poop.

B: No, oh no. I didn't research pooping. I'm sure it's pretty advanced. But you can actually get in from the back. And that actually makes it better. The shoulder assemblage can be a lot smaller if you can get in from the back. It's better.

C: So wait, before you summarize, what do the helmets look like?

B: I do know that the helmets do not have this. Remember the Snoopy cap? They called it the Snoopy cap. It was that white cloth thing. And the headset was in there. And they called it the Snoopy cap. But it got sweaty and nasty. That's gone. So now they're going to have the audio system. It's going to have this multiple voice-activated microphones inside the upper torso. So you can more easily and very efficiently communicate with the suit itself or with other astronauts.

C: Did I tell you my favorite part of wearing a spacesuit?

B: You could pee in it?

C: The little two-bump spongy assemblage that's inside the helmet. Because, of course, you have all these pressure changes. And you have to pop your ears. But you can't touch your face because you're in an inflated suit. Yeah. There's a little spongy bit that's mounted inside the helmet. And you lean forward. And it fits your two nostrils perfectly so that you can blow down.

B: That's awesome.

C: And pop your ears.

E: Talk about ergonomics.

B: What a cool idea. What a cool idea.

C: Yeah, that's my favorite part.

E: I want that in my car while I'm driving.

B: So the XEMU spacesuit sounds pretty wicked. And we will see it, just not in 2024. Maybe 2025. But I doubt that.

Scamming Teens (1:11:19)

S: All right, Evan, finish up the news items telling us about tech-savvy teens still getting conned online.

E: Yeah. Well, CNBC put out an article just yesterday titled Tech-Savvy Teens Falling Prey to Online Scams Faster Than Their Grandparents. Hmm.

C: Oh, no.

E: OK. So the article links to a report presented by a website called Social Catfish. Has anyone heard of that website before?

J: No.

E: I hadn't. Apparently, it's a service for finding people, a person search, put in this data and they'll tell you apparently where they are. But they do other things as well. And from their website, they say that this mission of Social Catfish is to help eradicate internet scams, which is a tall mission, eradicating internet scams. I mean decrease, minimize, OK. But I don't know how they're going to stop it entirely. But that's that's another story. Anyways, their report is titled Methodology of the State of Internet Scams 2021. And they said the purpose of the study is to equip people with the knowledge required to avoid becoming a victim. They give some statistics. A record $4.2 billion was lost by Americans to online scams in 2020. Victims losing their life savings and as a result, doing damage themselves, taking their own lives. So it's very, very sad. It accounts for well, basically, if you add up the three prior years, 2017 to 2019, online scams, $7.6 billion. So in one year, you've had this significant jump 2020 over the prior, compared to the prior three years. They analysed data that they compiled from the Internet Crime Complaint Center, also known as the IC3, which is a division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI. And they also examined data available from the Federal Trade Commission. And they brought in a professional detective as well. And they put together a whole bunch of data for us. So total money reported lost in 2020, $4.2 billion, as we said. And of the 722 people that they polled, 73% of those victims were too ashamed to file a report for the online scams. So what that means is that the $4.2 billion is the amount of reported money that people were scammed out of. But almost three quarters of the people who were victims of scams never reported it. So they think that $4.2 billion number is way low, but that's all the data they have to go with. They can't really know what the actual number is. 20-year-olds and younger had the fastest growth rate of victims. So in 2017, there were just over 9,000 victims who made reports. But in 2020, 23,000, over 23,000 people in that age group reported being victims. So that's a pretty good jump there.

S: But we don't know if that's an increase in scams or an increase in reporting.

E: Right. Yes, exactly.

S: Or what the relative contribution of each is.

E: So what's happening? What are the scams that are happening? Well, there's something called spoofing. $216 million lost in 2020 compared to 2017, in which they said $0 was lost in spoofing.

B: Wait, really? It's not that new.

C: Yeah, it's not that new.

E: That's what they're saying. Or at least these are the reports. Maybe nobody in 2017 reported it. And they put it into the classification of spoofing. And spoofing allows scammers to make their phone number appear as if it belongs to, say, your bank or credit card company or any other company with whom you do business.

C: It is true. I've noticed it. I mean, tell me if I'm wrong. This is totally anecdotal. But within the last two, three years, the number of spam telephone calls I get...

B: Don't even get me started.

E: Well, yeah, I mean, we all have anecdotes about that. That's definitely how it seems.

B: It's disgusting. The 80% of my calls, I just ignore them because it's just bullshit.

C: Yeah, and it's true. In 2017, I don't think that was the case. But I think Bob and I were confused because spoofing is also done via email accounts. And that's been happening for ages. But the specific telephone calls, that might be new.