SGU Episode 799

| This episode needs: proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 799 |

|---|

| October 31st 2020 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

Science is not perfect. It can be misused. It is only a tool. But it is by far the best tool we have, self-correcting, ongoing, applicable to everything. It has two rules. First: there are no sacred truths. All assumptions must be critically examined; arguments from authority are worthless. Second: whatever is inconsistent with the facts must be discarded or revised. ... The obvious is sometimes false; the unexpected is sometimes true. |

Carl Sagan, American luminary |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, October 28th, 2020, and this is your host, Stephen Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey everybody.

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening, everyone.

B: First thing I want to say is happy Halloween to those that have downloaded this podcast the day it was uploaded.

C: Ooh, Halloween.

E: Scary.

J: You know what's funny? I hate that whole thing that you guys just do.

C: You don't like spooky sounds on Halloween?

J: It's like the most not spooky thing in the world.

S: It's not spooky, yeah.

C: This is what a ghost sounds like according to the movies.

E: Sound like Bela Lugosi.

J: That had to come out of the 50s, right?

E: It is. It is a paper cut out from the 50s, no doubt about it.

C: I have the cutest Ruth Bader Ginsburg costume and I have nowhere to wear it to. I got like the great like pearl, lacy necklace thing and these wonderful earrings. And of course I am already a brunette and wear glasses.

E: That's right. That's right.

B: It's not hard to do her, is it?

C: It's a very easy costume.

E: Zoom or treat just call people around.

C: Just call people randomly?

E: FaceTime this person. Trick or treat.

C: I go, look at my costume. Okay, bye.

J: So did you guys hear that Alex Jones was on the Joe Rogan podcast?

B: So we're done with Halloween now?

C: There's some kerfuffle.

E: Oh, right Bob, poor Bob.

J: Yeah, so we're going to talk about it more on the live stream on Friday. But oh, my God, Joe Rogan formally fully jumped the shark about 10 times in a row on this one.

C: But he's had it. This isn't new. He's had Alex Jones on before. This is like a new thing. It's just the new. It's the first time since he did it on Spotify after his hundred million dollar contract, after Spotify said, Alex Jones, you can't have a show here. So that's a thing. But at the same time, I don't know, what do you guys? Well, I guess we're going to talk about it. But what do you guys think of the internal emails of the guys being like, listen, we can't start dictating who he does and doesn't have as a guest on his show?

J: Yeah, that's them just walking it back.

C: You think?

J: Well, I mean, look, if you're going to say that the information that Alex Jones conveys is not proper and they don't want to support it's really just a ridiculous technicality to say, but it's okay if he's a guest on anybody that has a podcast on our platform..

E: Not just any podcast, but the podcast.

C: But there I will say you're right, because it's a huge platform. But there is a big difference between just spouting whatever drivel you want to spout, unfiltered on your own show and somebody interviewing you.

E: It's not an infomercial, right?

C: No, you're getting pushback. You're getting people somebody saying, wait, wait, wait, wait, but I thought it was this way. And you're right. It is giving him a massive platform. But at a certain point, when does it become I understand saying we don't want your show because your show is full of misinformation on our platform. We're not going to condone that because that makes us look bad. But at a certain point, when does it become like censored, like really bad censorship? I don't know.

J: I don't think it's, I really don't look at look at it as censorship when someone has been classified as completely full of bullshit, completely full of lies and manipulation. I mean, this is a person that talked about the shooting that happened literally in the town that I was living in. And he said it didn't happen. He said that the parents were hired actors. He said the kids don't exist. All these ridiculous statements, this isn't this is way beyond like, hey, let's have have this semi-controversial person on and dig into the weeds with them. That's one thing. This is someone whose thoughts are dangerous.

C: Oh, yeah. And he has a direct line, not a direct line, but his thoughts have directly made it into the mouth of the president of the United States.

S: Well, it's not worse than that.

C: It was a massive audience for him.

S: We don't know if he believes anything that he's saying. I mean, worst case scenario. And I think this is a reasonable interpretation.

B: Sure.

S: Is that he's a con artist who's making it up to to con people and to sell crap.

C: Of course.

E: To sell his junk.

C: Well, yeah, he sells so much doomsday-

S: So, yeah, let's have a con artist on the show to sell their con, you know.

C: But he does that all the but Joe does that all the time. I mean, this is not that's the thing. This isn't new. Nobody should have been surprised if they really wanted to say, Joe, you can't have this guy on. That should have been part of the crazy contract they signed with him. They should have looked through his guest list and said, OK, but we're going to have some stipulations, my friend. I don't know. I don't agree with it. But it is censorship, Jay. It's not a First Amendment issue. This is a private company, but it is censorship.

J: I wouldn't call it censorship, but that's the definition of censorship. But it's their platform. They can just like just like us, we choose to not interview a lot of people on this show. We get we reject way more requests than we ever let through the gate. Is that really censorship or is that editorial policy?

C: That's different.

S: It's not really, it's an editorial.

C: No, it is different because you're saying we choose to. But Joe chose to interview him.

S: Yeah, we're criticizing that choice.

C: Spotify would be censoring that.

J: The actual news story here is that Joe Rogan is credulous and he's guilty of spreading horrible information. He is a very, very low research kind of guy like he'll do it on the spot research. Literally look things up as it's happening on his show. I mean, we do that to fact check certain things here and there. He's like, look doing this for an entire premise.

C: And we would never give, like you just said, an interview to somebody who we know is going to spout not just pseudoscience, but very dangerous misinformation during a very delicate political period where sowing distrust within the public actually has legitimate ramifications of harm.

S: I also think it's different if they're not acting in good faith.

C: In good faith, yeah.

S: If you suspect that they're not in good faith, then it doesn't matter what they believe. That's disqualifying. And I think there's a fuzzy line there. I see what you're saying about Spotify censoring Rogan versus Rogan's own editorial policy, unless they have an editorial policy that they impose upon their people. But if they don't, then-

C: Then that's a weird thing.

B: They've got to suck it up.

S: In fact, censorship.

C: Yeah. And that's the weird thing, too, because they're like, he can't have a show on Spotify. But Joe, go ahead and interview him.

S: Yeah.

C: So that's where I think it gets complicated legally. And I think that's why people are talking about this, honestly, because they're like, what just happened?

S: Well, listen, outlets are allowed to have quality control and an editorial policy. If a university doesn't have a professor who spouts conspiracy theories. Is that censorship? That's that's quality control.

C: No, I know.

S: That's having standards. That's academic standards.

C: But just the definition of censorship is just silencing something. Well, that's all it is. I'm not talking about First Amendment issues.

S: Are you silencing it because you are not giving it space on your own platform? No, I think it's censorship when an outside body tells you what you can have on your platform. If you're making decisions for your own platform, it's not censorship. It's quality control.

J: Like, I don't care if he if Joe Rogan has an editorial policy. I don't care if Spotify has an editorial policy. They both failed. Joe Rogan should never have had that guy on his show unless he was going to go mano a mano with him and try to and really tear him down and make him stick to certain points and actually try to get somewhere. But he didn't. He gave him a pass. He let him spout his bullshit. He did really a really lame ass attempt.

C: Yeah, it wasn't a debate. He platformed him.

J: He platformed him.

C: He absolutely platformed him. He said, welcome to my show. I will give you a cushy throne and you can say all the nonsense you need to say because nobody's been listening to you lately.

J: Right.

C: And that's not OK.

COVID-19 Update (8:25)

S: Let's pivot to the pandemic a little bit since we didn't even talk about it.

C: Oh, fun. Just throw some more on the dumpster fire.

S: Although I was up. I want to start by saying that I was on a radio. I was interviewed for a radio show this morning. This was Morning Answer Chicago for local Chicago radio station. So I'm getting a lot of requests for radio interviews. And most of them are because I wrote a blog about it. It comes up on the search. And so they all this guy wrote about X. Let's interview him. So this was about the article I wrote recently, which I talked about last week on the show about the declining case fatality rate of the pandemic. Like, why are not as many people dying? And so I don't bother researching local radio stations before I go on them, because it's not a radio station. I call in five minutes before I'm supposed to go on. I'm on hold. So I'm listening to the live broadcast for five minutes. While I'm waiting to go on. And it's immediately obvious that this is a right wing outlet in full pandemic denial.

B: That's interesting, though.

C: Weird. Wait, was it an AM station or an FM station?

B: Now I really want to listen to it. Or your interview anyway.

S: Yeah. Well, I tweeted a link to the interview itself.

C: Steve, was this AM or FM?

S: FM. It was fine. I mean, the interview itself went fine. You could tell that they're like trying to shoehorn all the information into their narrative. And I just was like just the facts. I didn't editorialize much. I just tried to be as factual as I could. So I think it came off well in the end. But it is amazing. It's a good just listening to them even before the interview and during the interview. It's a great example of motivated reasoning. They have a narrative. Their narrative is this pandemic is no big deal and they will endorse any point of view and take anything out of context in order to to make the point that it's no big deal. And that's the narrative. There's no balance. There's no exploration of things. It's just this. There's just hysteria and this pandemic is nothing. Really amazing. So that is so it's always it's interesting to get these little windows into the alternate information ecosystem that is out there. And you realize again, this is part of why half of America cannot even imagine how the other half of America is voting the way they are.

C: I don't think it's half and half. But I agree.

S: I'm just saying whatever, whatever it just represents, I'm not delving into it. But it's close. You know, it may not be half and half, but it's damn close. And because it's not that we have different opinions or that we have it's not just that we have different opinions or different ideology. It's tribal and it's because we're living in different universes of information. Every time I find myself saying, how can somebody possibly believe that I have to remind myself, it's because they are full of a completely different set of facts than I am. That's why. Because they don't have the information that I have, or if they've encountered it, it was from a hostile secondary source. As we say, it was from a source that was just portraying that was belittling that information.

J: Steve, what did they ask you and what did they what did they like or dislike about what you were saying?

S: So, I mean, again, I think you should listen to it, but it was like why so the death rate is dropping significantly from like March until August. We talked about this on the show and like, see, the virus isn't such a big deal. Like, well, it's still high. There was one study out of the UK that came out since we talked about it showed that the death rate of people who get admitted to the ICU with COVID dropped from 41 percent to 21 percent. That's a significant drop, but it's still 21 percent. That's a high death rate for any diagnosis that you get you get into the ICU with.

B: One in five.

S: Yeah. And then and it's still high for any for hospitalizations. It's like three percent, three, four percent. For anyone who goes into the hospital with a diagnosis, that's really high. And then I went through the various reasons why it's decreasing and they want that. It's just a matter of focus. Like that's because of all the great therapeutics we have now. It's like, well, it's only partly due to that. I did I acknowledged it was accurate regardless of the implications politically. Yes, that's accurate. But it's also due to all these other reasons like wearing masks reduces the severity of infections, not just the probability of getting it. And we've already killed off all the old sick people, the pandemic is moving on to healthier people at baseline. So, of course the the death rates going. I think that surprised me, though, because, again, it shows you like how motivated they are to make the case the way they want it to be. They came to schools. We're talking about kids going back to school. And again, I was like, yeah, kids should go back to school. The American Pediatrics Association said it's really important for young kids to be back in school and that we just need to give schools the resources to do it safely. And they were like, kids are great at wearing masks and social distancing.

E: I don't think so.

S: Have you like have you met kids?

C: Yeah, like, have you been around a child?

S: So that was that they were they were going to die on that hill. But I'm like, yes, kids are great at wearing masks.

E: Oh, my gosh.

C: It's weird to me, too, that it's like literally are. So they're not COVID deniers, per se.

S: It's like a flu.

C: They want to talk about the minutiae.

S: It's a bad flu. We didn't go crazy. We didn't have all this. They kept using the word hysteria when the swine flu came out or when this flu happened, it's just the flu. It's like, no, we have two hundred and thirty six thousand deaths in the United States with everything that we're doing, with everything that we're doing.

C: It's also not a flu. I hate it when people argue like this.

E: Right. But they don't know how else to equate it.

S: And again, they were taking the point of it's not going away, right? We're not going to eradicate it. So we have to learn to live with it. I'm like, yeah, you're right. We're not going to eradicate it. But we can minimize it until we get a vaccine. That's really the goal. The goal is to minimize death and spread of this virus until we can get a vaccine. And that as long as that takes. So let me just go over the numbers a little bit, because it's really amazing. Again, it's like we've been saying all along, we won't know where we are in this pandemic until we can look back. And so like we had that first spring surge. And again, it's like the graphs keep changing scale, to accommodate the new case. So it's like if you looked at the graph back in April, like there was this big hump of new cases happening in March and April. And then it kind of decreased a little bit in June in the US and the world it was pretty much still going up. But now that is that's a teeny tiny bump, because then we had this huge summer surge again in the US and around the world. And now we're having an even bigger surge. So this fall surge that we are now in the midst of worldwide and in the United States is bigger than the previous two surges. And that spring surge that was overwhelming at the time is now a little blip on the graphs that have to accommodate the current numbers. The worldwide bigger we're getting up to like five hundred thousand cases per day. In the US, we just had like last Friday, less than a week ago, we just had the greatest one day total of new cases-

E: About 90,00?

S: -in the whole. Over 80,000 so far for the pandemic. We were breaking new ground even even today. We're over 80,000 today. And today is not over yet. We may even break more ground before this day is out or this week is out before this podcast goes up. At least two hundred and twenty seven thousand deaths in the US. And now hospitalizations are starting to pick up because there's always a delay. You know, cases are going up now, hospitalizations. And now even the death toll is in terms of new new deaths per day, it's going up. Until we can look back with hindsight at the whole thing we won't really know like where we are in this whole thing. The worst is probably yet to come. And a lot of health professionals, health professionals. I happen to know a couple of professionals, but publicly are saying that this is going to be a rough winter. If this is where we are now at the end of October, this is, we have to really prepare ourselves for a rough winter.

C: It's so odd to me that people who think this is just a bad flu and that we just have to learn to live with it aren't willing to do the things that you have to do when you're living with a disease.

S: Yeah, but they think we don't do anything every year for the flu, which is wrong. First of all, we have a vaccine program. You get vaccinated. And also, it's already baked into the health care system, for example, that if you have flu like symptoms, you stay home. You do not go to work. So there already are things that we do to minimize the flu, but not as much as we probably should do. And now we have a more virulent, more deadly virus without a vaccine. Of course, we we have to do things again. Two hundred and twenty seven thousand dead in the U.S. If we did nothing, if we treated this like a flu, we would have two million dead rather than two hundred thousand dead. And if we want to keep it from getting to four hundred thousand half a million by the time we get a vaccine, it probably will get there. But if you want to keep that number down as much as possible, we got to do these things. Mask wearing, social distancing, that's a no brainer. We just have to do that until we have a vaccine. Everyone needs to be prepared. You're going to be wearing a mask in public for the next year. Just just accept it. That's it.

C: And we're used to it. It's not that hard.

S: It's not that big a deal.

B: Plus I love my Jack O'Lantern mask.

S: And then in terms of the "shutdown", that's the other thing they were like ranting about the shutdowns like, well, first of all, there's a lot of things that happen under that one label. It's not just you either completely shut down the economy or nothing. You could just ban large events that could otherwise be super spreader events. Or you could say restaurants have to have limit people or happy only be outdoors or whatever. There are things that there were different phases of the rules, different and that has to be married to what's happening in the community. What's happening in in the state, in the in the area it's not just like all or nothing. But again, their goal was to portray as this is nothing. It's just a bad flu. Don't worry about it. And anything else is hysteria.

E: I've already informed my clients this coming tax season and will not be seeing them in person. It will all be telephone and zoom. Yeah, that's it. So we already shut down. I mean, that's the spring. And we've already closed our office effectively. Yeah, because that's it. We're just not going to take any chances whatsoever there.

S: This is a bad virus. And we are not clearly we are not even seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. We are still in the midst of this. Now we're heading into a third surge bigger than the previous two. It is really just ravaging certain states in the US. And it does correlate with states that have less restrictive laws, states that don't require mask wearing, for example, or social distancing. They're the ones that are being devastated now by this. It's not a mystery what's happening. All right, guys. Well, let's go on to some news items.

News Items

Holiday Gatherings (20:30)

S: All right. And, Jay, the first news item is actually a COVID related one as well. We're coming up on the holidays. We've got Halloween the day the show comes out, which is the most important holiday. Right, Bob?

B: Of course.

S: Thanksgiving, our Thanksgiving plans are in flux right now. We honestly don't know what we're doing because of the of the pandemic. And then Christmas, Festivus, Hanukkah, all of those holidays, the seasonal holidays. What are people supposed to do during these holidays during the pandemic?

J: Yeah, the question is should we stay in your current bubble or whatever you use to refer to the people who you are co mingling with? Should you mix with other friends and family that you haven't before? And if you are going to do it, what does that mean? So the answer is there isn't really a crystal clear answer. There's going to be I'm going to tell you some things that are obvious. And then hopefully I'll tell you some things that maybe you haven't thought of that might help navigate the holidays. Really, it could be any reason that you have to get together with people. But we have two or three major holidays coming up in a very short amount of time. And it's good to think about it now before they happen. So right out of the gate, the best thing you can do is do nothing. Stay home, celebrate remotely and with just the people who are already in your current bubble. But if you have to do something else outside of that, what do you do? I think a lot of us are going to end up doing it to some degree over the holidays. So if you think there's a chance you're going to be seeing more people, then you got to start talking to them now, start talking to your friends and family who you're going to visit and be around right now about the whole thing. It was easier to make a decision about who you were going to feel safe with being around if you know what everyone thinks, right? If you really understand and know all the people in your in your extended family and all your friends and you're all on the same page and I'm saying like following the rules and doing what you need to do to be safe, then that's one thing. But if you're going to visit family, family and friends and you don't really know where everyone is, do you have a crazy uncle who refuses to wear a mask or do it, whatever it is you get what I'm saying. To avoid the huge fight at the event at whatever the holiday is, make the phone calls now. I recommend that you start a very friendly conversation with your friends and family, send out a mass email and avoid the confrontation and just say, hey you know, really thinking maybe it's a really good idea if we just follow what the CDC says or whatever, whatever the health organization is in your country. Kind of put the heat on them, take the heat off of yourself and say, just to be safe because of maybe it's because of young kids in the family, maybe it's because of people who have preexisting conditions that this type of disease would hurt, or maybe it's because of the older people in your life, make sure that you give them that information so they're thinking about those other people as well. I also recommend you bring extra masks if you're going to see people and you're at a holiday, people like Bob said earlier, people forget their masks. But just spend 30 bucks, buy a bunch of a handful of masks and hand them out to anyone that needs them. Just just to ease people's anxiety and make it easy on the person who doesn't have the mask, here you go. So if you can have the gathering outdoors, that's also highly recommended. So if you're not in a really cold climate, just do it outside, make it work. Or you could pick a meeting location that simply has more space. Get out of the kitchen and go into the living room in your house. Or figure out of all the people who are involved in that holiday, just who's got the biggest house, who's got the biggest room that you could do this party in and ask them if they'd be willing to do it there. That right there. That could save a life just by moving the event to a bigger space. Now, in the United States, different states and also countries, if you want to just add that in there they have different rules and different suggestions as to how many people can or should come together. So as an example, California health officials are suggesting that you limit gathering to three households, right? That means that three separate families in the groups that are contained in those families should get together. Other states have a lower number saying two. And even though your friends and family, if they aren't already inside your current bubble or your current immediate family, then you should treat them the same way that you would treat a stranger at the supermarket. Think about that. It doesn't matter that you know them. They should still be that guy at the supermarket that you're like, I'm going to stay six feet or more away from that person. That's the way you got to think about it. And it's hard to do because we love these people. We want to be around them. We want to talk to most of them.

S: Now we've done a lot of Zoom gatherings, and of course, they're not as good, but they're not bad. You know, they're it's you still get to talk with people and you'd have a bunch of people on at the same time.

J: That's one of the things I recommend. You should definitely if you can, or if you opt out of the holiday, you could say, hey, but maybe we can get together with a Zoom meeting. You could have some fun events over Zoom. You can have parties. We just had my mother-in-law's 70th birthday party over Zoom, and we invited everybody and a ton of people showed up. And it was actually a really beautiful and wonderful event that we did. So here's another thing that I recommend that you do. The the COVID tests now are available. A lot of people are getting them. You could call your doctor up and say, I'd like to get a test at the latest possible date that I can before the holiday. Schedule it now. Talk to your doctor about that now.

B: I'm getting one tomorrow.

J: Bob, that's great. And you should you should encourage people to do it. Even if you test negative, that doesn't mean that you're not infected. It could take between five and seven days to be able to actually test positive for COVID after you are infected. So that's a really big amount of time that you could be walking around infecting people and you don't even know it. So, like I said, get tested as close to the event as you can. One of the best things about the holidays is the food. You're going to want to continue talking to people while you're eating. Now, it's possible that while you're eating and talking to someone, that something comes out of your mouth and it travels up to six feet away from you. A little piece of food or spit could easily travel six feet when you're talking. If you see in the right lighting, when you see people talk, they are spitting the entire time. You'd laugh, Cara, because I know you know.

C: Yeah, it's gross.

J: It's constant spit.

C: A cloud.

J: Try not to be over overly judgemental of your friends and family either way. If they're mask wearers or not. Just keep it cool. It's a holiday. Just keep your distance. That's what you got to keep in mind.

S: Well, let me push back a little bit on that, Jay. I think that one of the biggest mistakes that people make is they think, well, because I'm distancing, I don't need to wear a mask. Well, we have good ventilation, so we don't need to distance. These are not one, you don't have to do one of the above. You have to do all of the above. If you're going to be inside, you need to keep your distance, wear a mask and have good ventilation and have good surface hygiene. I think don't think that because you're six feet apart that you then can take the mask off. Six feet is with a mask. It's really 12 feet without a mask. If you really want to be safe. So just don't fall into that fallacy of thinking that if you're doing one thing, you don't have to do the others. You really should be doing everything.

C: Right. And just because you've gone outside doesn't mean rip the masks off and stand close to each other. I see this all the time. The second people leave the store, they don't wash their hands. They're just ripping the mask off their face and still walking through a crowded parking lot. And this is not safe. But I mean, Jay, I'm my concern would be if you do have the crazy uncle who thinks it's a hoax and isn't following any of the guidance. This might be the year that you don't see the crazy uncle.

J: Yeah.

C: You know what I mean? Like, at a certain point, there is nothing you can do, and it's only going to cause trouble and heartache. I think one of the biggest concerns that I see, it's like a cognitive bias that a lot of us have, too. And I noticed myself having it with a friend just the other day. One of us said to the other, well, I trust you. And then we realized, oh, that doesn't matter. The virus doesn't care how much you trust each other, how good of friends you are, how much you love each other or how close you are. Because the truth of the matter is you could be doing everything right and still catch it and still put other people at risk. So the important thing here is that it's a numbers game. The higher the number of people in a space together, the higher the likelihood that you're going to contract the virus. If there are only two of you, your likelihood is significantly lower than if there are five of you. And then there are tipping points. Once you get past, I don't know, 10, 20, 50, it becomes almost a 100 percent guarantee, it becomes very likely that somebody within the group would have been exposed and potentially expose others. So we just have to think statistically. Now is the time to think like skeptics, more than anything, which isn't easy when we're like, oh, but it's my cousin. I love him and I trust him. He's not going to get me sick. It doesn't matter. It has nothing to do with that.

J: First off, thanks for clarifying those points, guys, because I was talking more about just don't be a jerk. Try to keep it civil. A lot of us are going to run into people who don't want to wear masks and politically might be in a different place than you.

S: I think the solution there, Jay, rather than saying don't be a dick about wearing the mask is instead have have an understanding beforehand. You don't want to hash this out on Thanksgiving. It's like if you're if you're getting together saying, I want everyone to understand what the agreement is, we're all going to be wearing masks. And if someone says, I don't want to wear a mask, then make other plans. Plan accordingly, I'll say.

C: But you get to sit at the kids table outside.

S: Don't leave it. Don't just sort it out on the day. I would say just pre plan everything.

C: What do you think the sales are going to look like for, like, sad TV dinners of like turkey and potatoes and cranberry sauce? Because I bet you there's going to be a lot of people like me who are like, I live alone. I'm not going to be with people. I'm not going to cook a damn turkey. I want the taste, you know?

J: Well, Cara, I'll tell you something. So when we go to Colorado and visit my sister and brother-in-law, sometimes we we actually cater Thanksgiving because of the amount of people and just the amount of the difficulty of having to cook that much turkey. There's only one oven in anybody's house, and we couldn't possibly cook enough turkey. But I bet you that you could buy a wonderful and complete Thanksgiving meal or special meal.

C: For one, because they just make like, yeah, that's probably true. There are probably a lot of restaurants that are doing like stay at home Thanksgiving dinners.

S: Yeah, Cara, Cara, they have the loser Thanksgiving special. Just ask for that.

C: Yeah, exactly. That's all I need, because I'm telling you, I am not going to slave away in the kitchen for like eight hours to sit alone and eat my and have so many leftovers that I'm just going to throw away.

J: Cara, if you're lonely on Thanksgiving, if you're really alone, I will get an iPad and I will see you at the table with us and we can have dinner together.

C: That's really cute. Thanks.

Water on the Moon (31:40)

S: All right, Bob, this is actually, I think, the big news item of the week, is an update on our knowledge about water on the moon.

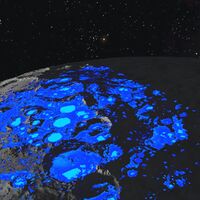

B: Two two studies recently released show not only the best evidence for water on the moon, but evidence for far more than we thought. Not only is it a new shadowy hidey holes, but also out in the sun every lunar day.

E: How's that possible?

B: Don't don't get your hopes up for that last one. OK, so now these two studies were recently published in Nature Astronomy. So check that out if you want to read the details. For the longest time, the moon was synonymous with the expression bone dry, right? I mean, when especially when we went there, actually physically went there in the 60s and confirmed all that nasty regolithic moon dust that was everywhere. That's the you know, that's what dry means. When there's dust everywhere, it's dry. How could water be there or or any other form of water? But that changed the past decade or so when we found evidence of water and permanently shadowed craters. So now it's just like if you're up on this stuff, you're just like, yeah, there's water on the moon. You just you just take it for granted now. But now there's more stuff that you're going to be taking for granted and in some surprisingly new locations. So we know that there's ice in some of the big craters, right? Because they're they're they're permanently shadowed and it gets there from whatever asteroid comets. And if it gets there, it stays there because the sun never hits it. But what about on a smaller scale? So using the NASA robot Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and its temperature observations, plus other mathematical models, they have shown that smaller craters and indentations that they call micro cold traps from basically from the size of, say, a penny to a yard or so could hold ice just as well, but just in smaller amounts, right? So these traps could be consistently frigid at, say, minus 260 Fahrenheit or below. The temperature can keep ice on ice, if you will, and it could remain unchanged for a billion years. So what these micro traps lack in size, you might think, oh, a penny, a yard, big deal. But what these micro traps lack in size, they apparently make up for in their plethora index, which is a term I made up just today, and I kind of like it. So they estimate that 15,000 square miles of the moon surface could be covered with them. Lead author Paul Haynes of the Department of Astrophysics at the University of Colorado said if you were standing on the moon near one of the poles, you would see a whole galaxy of little shadows speckled across the surface. I like that imagery. So now the second study is even more interesting in some ways. The observational instrumentation this time was not an orbiter, but SOFIA, which is an acronym for Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy. Now, it's this is a dish. I think it was a two and a half meter dish that's on this modified Boeing 747 airplane that flies high in Earth's atmosphere, above 99 percent of the atmospheric water, which is critical, depending on what it's actually looking for. And it's looking at the reflected light from the moon. So within that light is an emission line, a specific colour, if you will, that we can't see with our native eyes. It's the far infrared with a wavelength at six microns. And only one thing we know emits it, water. Other studies before that may I think they were looking at, say, three microns, which is good, but it's not as diagnostic as six microns is. That's the one where we just literally if you see that, yep, there's water there and not some other some fake out of other elements or other molecules. Now, this water was found in the Clavius Crater near the Southern Pole and it's exposed to the sun. They were looking at it when it was when it was sunlight. The sun was shining. I was not hidden away from all the photons like some like some of the other water. So the water concentration is about 10 to 400 parts per million, which is really big. I don't think there's anything observable in the solar system that has more of a concentration. Maybe there are a couple of things, but it's close to the most concentrated amount of water outside of Earth that we know of in the solar system. Casey Honable of the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology said in a NASA press conference, that's roughly equivalent to a 12 ounce, 350 milliliter bottle of water within a cubic meter of volume of lunar soil. That's pretty good. That's not too bad for such a dry, dusty place. But and you knew a but was coming. This isn't actually water or ice. It appears to be just scattered molecules. Didn't see that coming, did you? So, yes, just molecules, not water, not ice. So how did this happen? So one theory, one possibility, and we actually covered this on the show not too long ago, was that the solar wind from the sun carries away some of our atmosphere and deposited some of the H2O on on the moon. And actually, that's what devastated the atmosphere on Mars. But more likely than that, probably, but this is probably the reason the water probably came from micrometeorites and tiny, tiny pieces, really tiny, like you need a you need special help to see them. They're so tiny microscope or whatever. They come off of asteroids or comets, which can have a lot of water in them, even the asteroids, not just the comets. And if they impact the moon, if these micrometeorites impact the moon or the or the larger bodies impact the moon, the impact can melt some of the material, right? Forming glass beads with the water molecules inside. So researchers point out that it's also possible, if less interesting, that these watery molecules are distributed in the empty areas around the dust grains of the regolith. But I think the consensus, though, here for at least these scientists is that it's in these glass beads. So that explains why we're seeing this water on the surface when the sun is shining, because the waters in these glass beads probably were hidden between the dust grains. But it also means something else that's not fun. We're probably never going to use this as a water source, picking up molecule at a time, even though even though there's a lot of it, it's just not a good way to do this.

S: It's like Bob, can we find some way of extracting it, like heating it and just evaporating all the water molecules?

B: I think the effort is just all right, I'll give you an analogy. It's picking it up when it's just molecules. It's like downloading porn on an old 14-4 baud modem instead of a cable modem. Sure, you can do it. But why when there's actually ice, there's actual ice ice in craters that are not too far away. So this is not a convenient way to do this. Unfortunately, at the NASA conference, they were talking about how this is motivation for going going back to the moon. And it's not. This discovery is interesting scientifically, but it's not motivation for going back to the moon. And it sounds like a total political spin on which is which is sure, you got to bring in politics for some of this stuff. But science is science. And it's in a lot of ways it should be inviolate. And and that kind of stepped over a line there, I think. So now what's the benefit? Oh, big deal. We found there's a lot more water on on the moon. Well, yeah, this is this is this is huge because think about it. I mean, it's still in 2020 costs us thousands of dollars for every pound that that we launch out of our nasty little gravity well to the moon or anywhere else outside out of the earth. So that's a lot of money. And if our moon base alpha people, they're going to need they're going to need water not only to drink, but you could also make it into rocket fuel. How convenient is that? So if the water is already there and a lot of it, it seems, a tremendous amount. It's really a no brainer to save the countless millions that we'd otherwise spend having to launch water when it's already there. And now there's even more than we thought, even if some of it is kind of inaccessible. There's still you've got those little those little micro crater things could be all over, not just they they found it by this one crater near the southern pole. But this could be in far bigger areas around the surface of the moon. So, yeah, very interesting stuff. I can't wait to see step two of this research and see how ubiquitous is it? You know, what's the plethora index for the rest of the moon surface, not just this one crater?

S: You're right. It may not be the lowest hanging fruit for water on the moon. But the more we try to have a sustainable colony on the moon, I think at some point they'll probably be extracting every molecule of water they can get would be my guess. But it's hard to predict.

B: I mean, a low hanging fruit is pretty big and heavy now. So, yeah, at some point they may start dipping into that.

C: Yeah, but some city on the moon, how much water do you need?

B: Yeah, but yeah, there is a lot. There's there's a lot there. But yeah, I don't I don't know if it'll ever be feasible to to make it really efficient. Who knows?

S: Yeah.

Murder Hornets Murdered (40:35)

S: So, guys, quick update on the murder hornets. You guys remember those guys, right?

C: Murder.

S: So if you recall, they found-

B: Pandemic stole their thunder.

S: -giant Asian hornets on the west coast of the United States. But no nests. They had not discovered any any actual established nests. And the question was, were these just individual interlopers, that hitched a ride on produce or whatever.

E: Clearly, that's the case.

C: Clearly, that's not the case.

E: We don't have to worry about nests.

S: Although it is true that some people did discover a giant Asian hornet or a murder hornet nest in British Columbia in Canada, which they destroyed. But there but there haven't been any in the United States. Entomologists were on the job. They wanted to know for sure whether or not there were any of these nests established. So they kept their eye out for any sightings of any individual hornets. They're pretty distinctive because they're so huge. They have a wingspan that can be up to three, three and a half inches. And they have a stinger that is six millimeters long. You don't want that. They could they could sting you through a beekeeper suit. And you said the pain is like getting hit with a sledgehammer.

C: Fun.

S: Yeah, the venom that they inject you with is extremely venomous. It's very painful. And it's a lot of it, right. They just inject you with a lot of very caustic venom that hurts a lot.

C: Yeah, and there are deaths reported. It's probably not the biggest concern is that people are going to get stung and die. That's actually very, very low risk. But they wipe out apiaries. That's the problem.

S: The concern is that just a few, a few of these hornets can wipe out an entire honeybee nest in a few hours. Each individual one killing hundreds, they have these giant mandibles and they just go around just decapitating every bee in their in their wake. And then not only bees, they also kill mantises and they kill lots of other insects as well. They are like really the apex predators of the insect world. The scientists recently found a living murder hornet in Washington State. As you know, they did.

C: They followed it?

S: They didn't follow it directly, but what they did was they tied a teeny tiny little radio transmitter.

E: They tagged it.

S: Oh, and then they let it fly back to its nest nest.

E: Nest?

S: And then they followed. They followed the signal back to the nest. Then they took a vacuum and they sucked all the hornets out of the nest. They killed most of them. They did keep a few living specimens for genetic analysis or whatever. And then for a good measure, they cut down the tree in case there were any other nests in that tree.

C: Geez.

J: Wow.

E: And then they brought in a back out.

J: Bomb.

E: Yeah, right. Dug a 30 foot crater.

S: I mean, eradication was the goal. If we miss one nest for any significant period of time, it's going to spawn other nests.

E: Oh, boy. It's like cancer.

S: Once it gets beyond a certain point, it's going to be impossible to eradicate it. They'll propagate faster than we could locate and destroy them. This is really the kind of thing you have to nip in the bud. The thing is, we don't know if we've done it. Yeah, they found and destroyed one nest. We don't know if it's the only one. If there are more, it may already be too late. And this could be devastating, devastating to the pollinators in North America because it's an invasive species. And that means that it doesn't have any natural predators to keep its population at bay. And also the native pollinators have real no defenses against it. Honeybees are basically defenseless against it.

C: Except for the bee ball that they make.

E: Oh, yeah, they do have a defense, right?

C: Yeah, it's just not, it helps. But at scale, I think they still are facing like a pretty big predator.

S: Yeah, I mean, it's just a just a pressure. Another pressure against a nest that added to everything else. Colony collapse disorder is going to just could be devastating. And as we've discussed previously pollinators are kind of important to our food supply.

C: Just kind of.

S: Yeah.

E: So do we have a responsibility to eradicate this species? I mean, is there justification in that if we could?

C: In the U.S.? Yeah, absolutely.

S: In North America. Yeah, because they're not native to North America. In Asia, I mean, they're native to Asia. They've kind of already reached their equilibrium there. So not that they're not an issue. Obviously, it wouldn't be the same kind of problem that it would be by introducing this kind of aggressive species to an environment that's not adapted to it. It was like the European starling, which I know I've said on the show before. I totally despise because there's are very aggressive birds that displace a lot of native birds and they were introduced. And then still almost a century later, the local populations have not really adapted to this invasive species, and they're taking over. They're really devastating local bird populations.

E: They're here in Connecticut, right?

C: They're everywhere. They're all over the U.S. That's the bird, Steve, that I have on my shelf because I taxidermied it. Because it's really easy to get specimens since they're abatement animals to taxidermy.

E: One down a billion to go.

C: But yeah, Evan, like it's very common to have national eradication efforts for invasive species that are, throwing the ecological balance off. So we do I think it is a moral imperative and you see it as a function of conservation quite often to have to go in and actually kill or cull is the word usually used species that are detrimental to native populations.

S: Yeah, absolutely. Just ask Australia.

E: Where those frogs go, I brought in.

S: The cane toad, right? They love the cane toad. So, yeah just flying in and out of New Zealand. They are obsessive about protecting themselves from any kind of invasive organisms. You can't have dirt on your shoe when you go into New Zealand.

C: But they have I have lots of things made out of possum from New Zealand because they're invasive there.

E: That's right. And you're expected to if you see one while driving your car, you're expected to kill it with your car.

C: Right. So it's it's very easy to get your hands on like nice possum gloves and hats and things. And they're very warm.

E: Possum jerky.

S: I'm wearing possum socks right now.

C: Nice. How random.

S: Because they're it's getting chilly up here.

E: Yes, it is. Might be snow on Friday.

S: By the way, possums in New Zealand are very different from what we call opossum. We call them possums, but it's spelled opossum here. Different species, totally different animal.

High Value Plastic (47:31)

- Most plastic recycling produces low-value materials – but we’ve found a way to turn a common plastic into high-value molecules[4]

S: All right, Cara. This is a follow up news item on our war on plastic. Not really a war on plastic is plastic is fine. But we've got to do something with all this plastic. And maybe there's some light at the end of the tunnel here.

C: So we all know that plastic is a massive problem. And maybe we can visualize how massive that problem is a little bit. I've found a couple of sources that have, I think, done a good job of helping put this into context. So plastics came on the scene about six decades ago. Since then, we have produced globally about 8.3 billion metric tons. That might not be a meaningful number because it's just massive and hard to hard to visualize. One way to visualize it is that each year we throw away, just throw away enough plastic to rebuild the Great Wall of China, just rebuild it in plastic. It's estimated that that number is going to be high by 2050 it'll be 12 billion. I actually think it's going to be higher than that.

B: [sing Barbir Girl tune] Life in plastic. It's fantastic. I'm a Barbie girl.

C: So by 2050, estimate 12 billion metric tons. So we're talking, oh, and that's just in landfills. 35000 times as heavy as the Empire State Building. There's a lot of plastic, a shitload of it ends up in the ocean. A big study came out in 2018, one of the first of its kind that kind of analysed how much plastic we're throwing away and what's happening to it. And they found that of the just over 8 billion metric tons that have been produced so far, about 6.3 billion metric tons went into the waste stream. So that's a big percentage. It's well over half of the plastic that had been produced was already being thrown away. And only 9% of that total had been recycled and not the gross total, the net total, just the plastic that had been thrown away of the 6.3 billion metric tons, only 9% had been recycled. Close to 80% was in landfills or in the environment. So litter, ocean, plastic breaking down to form those small plastic particles that fish and other marine life see as plankton and eat. You've heard conversations about the Anthropocene actually being demarcated in the future by plastic conglomerate, which is a word that some people have coined for the fact that there will be plastic in the rock. That is how they will know the plastic age. I mean, it's horrible.

E: Oh, there's plastic in us, right? I mean?

C: Oh, yeah, there's plastic in us. There's tons of plastic in us. I pitch Steve a plastic story like every other week. I think there was one last week about like baby bottles and microplastics and just it's horrible. So the problem, one of the biggest problems with plastic, as we know, is that it doesn't break down. It's an amazing material. And so I do think sometimes when we're like plastic is evil, we should take the time to talk about why plastic is so ubiquitous. It's solved so many problems. Plastic allows for sterile packaging. It's lightweight, so it's more energy efficient to ship plastic, products in plastic than in glass and sometimes in metal. Plastic is obviously really important for biomedical sciences. It's really important for patient care because you can sterilize it again and you can make things disposable cheaply.

E: It's not like we can have our modern society without it. We cannot just be done with it.

C: Yeah, not to this extent. But obviously, there are many places where it's absolutely unnecessary, like in single use plastics for like consumption, not for medical purposes. I personally believe there's no reason that water or soda or anything of that nature should ever be packaged in plastic. But this is a regulatory issue. It's not on the shoulders of consumers wholly, even though the plastics industries have done a brilliant job of putting the onus on us. But that's beside the point. The point of this news article that I'm interested in diving into is how are we solving the problem, right? And there are multi-pronged approaches. Some of them are working, some aren't. It's not the brightest of futures right now, which is why we need really brilliant people who are doing brilliant things in the laboratory. In enters Susanna Scott from the University of California, Santa Barbara, along with her colleagues at Illinois, Urbana-Champaign and Cornell, who are chemists. And they are like, OK, usually when we reuse plastic, reduce, reuse, recycle, right? When we talk about reuse and recycle, what we're really talking about is taking plastics that have a particular quality and melting them down and then reforming them to make something else out of the plastic. The problem is every time we do that, it degrades. So unlike glass and metal, which tends to be, to a large extent, indefinitely recyclable because you can break it down and put it back together and break it down and put it back together, the quality of plastic gets worse and worse and worse every time you do it. And eventually it becomes useless. And it definitely is not useful for the high quality utilization that it came with before. And part of that is because when you melt plastic, a whole bunch of nasty stuff happens. You guys have seen before you've thrown plastic on a campfire, right?

E: Not deliberately.

C: You've seen what happens. Sure. Yeah, because it smells horrible. Or you've seen in developing countries where they actually burn plastic for cooking fuel and it's really, oh, it's very dangerous.

B: I love the smell of carcinogens in the morning.

E: No kidding.

C: But I mean, it's horrible, but it's also in some ways the only option that they have because it's a cheap and to them, renewable, sadly, resource because it's washing up on their shores.

E: Right, right. Oh, gosh, some of those shore pictures are just nightmarish.

C: And so so you guys hit the nail on the head, right? I love the smell of carcinogens. It smells really bad. There's a lot of toxic stuff that's coming off of that. And of course, it's breaking it down in sort of a willy nilly way. But what these chemists realized is that what if we actually, instead of grossly breaking down the plastic, broke it down at the molecular level with intention so we could take these polymers, these big, long chains which actually make up the plastic composition. And of course, there are lots of different kinds of plastics. They specifically are working with polyethylene. And they said, what if we develop a process by which we actually like knock out some of the carbon molecules or at least release their bonds that hold the thing together and break it into teeny tiny pieces that way, then when we can recombine them, they still maintain their shape and their structure. So they'll be able to maintain some amount of integrity for use. And one of the biggest problems with this catalytic reaction is that usually it takes more energy to do it than it's kind of worth in the end. But they sort of developed a process that actually utilizes hydrogen to then remove the hydrogen from the polymer chain. So it's like the hydrogen itself is what's cutting the bond and then it's released and then it cuts more bonds and then more is released and it cuts more bonds. But it's self-limiting because once it gets to be too small, it no longer functions. So it replicates multiple times, but then it actually finds sort of an equilibrium point where it can't do it anymore because the molecules are too small, which is great. It just breaks down or slows down naturally. And what ends up happening is that the solid plastic that you're used to seeing turns into a liquid, but it doesn't escape a lot of gases. And that's really the problem with a lot of breakdown processes for recycling plastic, is you melt them at high heat, a ton of gases come out, they're aerosolized, there's all these benzines and as you mentioned, carcinogens that come out into the air. And the polymer chains themselves are all like warped and they lose their integrity. But if they use just the right amount of low heat in this very specific plastic where hydrogen is an important part of the catalyst, they're actually able to recover the liquid and the liquid that's recovered is mostly what are called alkylbenzines, which alkylbenzines are benzene derivatives. And they're like a big subset of aromatic hydrocarbons, like you might have heard of toluene, and that's a really like a kind of common one that most people have heard of. But the cool thing about it is that they have a commercial use. They can be used as detergents and those detergents have a pretty big market value. I think it's something like nine billion dollars annually. And so a large these researchers think, of course, they haven't done this yet at scale, but at least in terms of proof of concept, which they are able to physically do this process, they think that they're going to be able to recapture a lot of this polyethylene or what was originally polyethylene and aromatize it into these long chain, what they call alkyl aromatics. So alkylbenzene groups and actually be able to sell those things commercially. They call this upcycling. It's not a new concept. Upcycling has been around, but they think that they've developed a really useful way to do it that actually provides a good marketable product that has an economic value and will hopefully clear some of this waste plastic that really is useless. It really is doing nothing except gunking up our rivers and streams and roads and taking hundreds, sometimes thousands of years to break down and pollute the environment. So it's one of many tools that I think scientists are slowly but surely working on developing. And hopefully, like we mentioned in the past, when we talk about space junk and satellites and when we talk about a lot of other changes to regulatory changes to industry, hopefully these kinds of mitigation efforts can be worked into the planning at the forefront for plastics manufacturers. I think that's a long way down the line. I do think that's a little bit of wishful thinking since we don't even yet have the political will to push back and say, no, like, don't put coke and Sprite and bottled water in plastic. Like, we just need to ban that out. But we haven't been able to do it.

E: Do we really need those?

C: Right. Exactly. We've banned plastic bags in L.A. We polystyrene containers like foam takeout containers you can't really have in most places. So there are certain places that are a little more out in front of this than others, but at least this is a problem that's being worked on. And at least it does seem like there are some small scale, maybe eventually they'll be scalable solutions that are actually friendly to the market too, which I think is really important to have that economic piece as part of the puzzle.

S: Yeah, I agree that at the end of the day, there's got to be an economic stream that works, otherwise it's not going to happen.

C: Otherwise, yeah, the plastics manufacturers, they're just going to keep lobbying and they're just going to keep I mean, they're going to do it anyway. But their lobbying efforts are going to work because they're going to be able to say, look, I'm adding to the economy because I'm making these products and what else is there? So, yeah, it's a multi-pronged effort, I think, of prevention. And that's one of the things that we're not doing enough of, but also mitigation after the fact. And at least I'm seeing some hopeful news on that front.

S: All right. Thanks, Cara.

Exoplanet View of Earth (59:31)

S: All right, Evan, finish up with this item. This is something we've mentioned before, but it's another sort of take on exoplanets, can their view, their ability to view the Earth.

E: Yeah. Yep. And how can you not love a report that starts like this? Three decades after Cornell astronomer Carl Sagan suggested that Voyager 1 snap Earth's picture from billions of miles away, resulting in the iconic Pale Blue Dot photograph, two astronomers now offer another unique cosmic perspective that some exoplanets have a direct line of sight to observe Earth's biological qualities from far, far away. I love that. That is a romantic thought. I mean we talk about exoplanets regularly on this show, but almost always from the perspective of Earth. To just wonder what other potential people or whatever out there are capable of detecting the Earth and what they might see. I mean, that's just that's really an incredible thought. But there are also practical questions that arise from the thought of Earth being an exoplanet. And we've talked on the show before about how an exoplanet's orbit must be aligned with our line of sight in order to observe these transits. But reverse that, you ask the question, from which stellar vantage points would a distant observer be able to search for life on Earth in the same way? Well, Lisa Kaltenegger, who's the associate professor of astronomy at the College of Arts and Sciences and director of Cornell's Carl Sagan Institute. I didn't know there was a Carl Sagan Institute. That's wonderful. And Joshua Pepper, associate professor of physics at Lehigh University, have thought about this question and they've endeavoured to answer it. They put out a paper and it has identified over a thousand main sequence stars, which are in some ways similar to our sun, that may contain Earth-like planets in their own habitable zones, all within 300 light years of Earth, which should be able to detect Earth's chemical traces of life. And their paper is called Which Stars Can See Earth as a Transiting Exoplanet. It was published October 21st in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. So, yeah, signs of a biosphere in the atmosphere of a transiting Earth, such as the oxygen we have, our ozone, methane, could have been detected, get this, for about two billion years of Earth's history. That's a nice chunk of time. That's a nice chunk of time for other potential civilizations out there to have had a chance to detect the chemical qualities of Earth.

B: Wow. Yeah, that's a good chunk of time.

E: Yeah, big chunk of time. By the same right, we should also, those also become prime candidates for us as well, knowing that it takes, well, we have one set of information to work off of our own Earth. We know that it took billions of years sort of to get to a technological state. So you can eliminate certain stars based on their short lifespan. You can probably, in some ways, make some eliminations there. They created this list of these thousand closest stars using NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, and we've talked about the amazing work that TESS has done on the show before, but they have more precise measurements and they've been using latest data analysis. It's called the Gaia Mission Data Release 2, or the DR2 Gaia Collaboration from 2018. And basically what they've done is they've been able to exclude certain stars that have evolved in a certain way or those that have poorly measured stellar parameters. They've been able to basically refine and focus in on more of these candidates. And as the lead author says, if we're looking for intelligent life in the universe, that could find us and might want to get in touch. We've just created the star map where we should look first. So I think that's maybe the takeaway here is that we've come up, is that they've come up with a way to focus our searches a little more carefully and with a little more enthusiasm to these places that are able to see us and aren't thousands or millions of light years away, but simply hundreds. In fact, the closest one that they identified is only 28 light years away from our sun. Twenty eight years, hardly anything.

J: Yeah, that's not far at all.

B: Twenty eight times, was it six trillion miles? Not too bad.

E: Well, in a cosmic sense, not bad at all. It's just a real cool and different way of thinking about exoplanets and that we are an exoplanet to a lot of other to a lot of other planets out there.

S: To every other one.

E: Well, the ones in our plane.

B: Well, not just that, assuming their life is similar to ours, they could be so foreign that they look at us and be like, oh, look at those waste chemicals in the atmosphere. Who the hell wants that stuff? No, no, that's that's our type of life.

E: They've categorized it by the types of stars such as cool red M stars and K stars and G stars. Our star is a G star, by the way. So they've been able to identify some of those candidates as well. But that's cool. You know, what would they say? Three hundred years ago. Where were we three hundred years ago? Think about every how different the world was then. We're like all our modern technology has happened since then.

S: All right. Thanks, Evan. Jay. It's Who's That Noisy time.

Who's That Noisy? (1:04:05)

- Answer to last week’s Noisy: Preemie

J: All right, guys. Last week, I played this Noisy.

[_short_vague_description_of_Noisy]

So any guesses?

C: I love it.

J: Anybody?

S: I mean, I think I know what it is.

B: Some A.I. that's been designed to mimic a baby bird.

J: So a listener named Rachel-

B: No?

J: Benasia, Benasia, Benasia.

C: Ignored.

J: I watched this is what she wrote. I watched The Lion King too many times as a kid. So I'm going to guess these are baby hyenas. It's kind of funny. They're not baby hyenas, but I got to laugh out of that. A listener named Kate wrote in, "Hey, Jay, I think this week's Noisy involves pandas. The vocalizations sounded very similar to me, perhaps two individuals involved in courtship or one responding to the advances of another."

E: I know pandas only sneeze. I saw a video on YouTube about that.

J: Not correct, but that is an interesting guess. Richard Owen wrote in and said, "Hi, Jay, love the show. Keep up the good work. I think this week's Noisy is a Kea that's spelled K-E-A. It's a cheeky New Zealand mountain parrot", not a parrot. So what do we got now? We got a we got a hyena. We got a panda and we have a parrot as guesses. And then this guess is the first one that sent in this guess. And this guess was sent in by dozens of people and little variations, but all revolving around the same idea. This is Ed Beals. And Ed wrote, "Hello, I hope this message message finds you well. We are doing remarkably remarkably well here in Nova Scotia." And then he goes on to tell me about COVID. But I will go fast forward to where he talks about the Noisy. He says "near the end of this week's Noisy, I started to imagine I was hearing a loon call trying to emerge. Could it be a young loon learning to call?" So I did a little research because I was curious as to why so many people were writing in this particular bird. And I did find some examples of a baby loon and an adult loon. And I think you're going to recognize the adult loon sound.So take a listen, you're going to hear the baby first and then some adult variations on the adult call. [plays Noisy] That's the one you might recognize.

B: Oh, yeah.

J: Very forlorn, almost scary, very good for Halloween. So, yeah, it's you know, I'm not hearing it. A lot of people guess that I'm not hearing it. But I just thought it was interesting that so many people guess the same thing. So nobody won. Nobody got it last week. And I really thought this is funny how I always try to play the game in my head, like how many people are going to be able to guess this. I thought that there would be a certain job that people have where they would guess it. So, Steve, what's your guess?

S: I think it's a preemie.

J: It is a premature human baby. Listen again. 30 week old.

S: Yeah, because I've heard that.

[plays Noisy]

B: The hell?

J: Now that you say that, now that you say that, Steve, I've heard that noise, too. I can't remember where, but I do believe when my wife and I had our our son that there was a premature baby that I heard crying.

S: Yeah.

J: And then once you kind of hear it, you'll attach that sound to a human baby and it'll start to kind of make sense.

S: Yeah. And some of them, some of the the cries sound more human than others, and definitely you get fooled by animals that sound more human than they have any right to.

B: Like two turtles having sex. I kid you not.

J: So the Grace Holland wrote in, and she said that she predicted that people are going to guess it's a baby animal. She said, "I am a neonatal ICU nurse, and this is a recording I made of a one day old baby who was born at 30 weeks gestation, weighing 2.5 pounds. The background noise is the sound of the suction tumming. But she said this was the sound. It was one of those moments that hit her of how incredible her job is. And God, thank you so much. Like, this is a prime example of a wonderful Noisy that you just don't get to you know, I would never stumble on the situation where I'd have the wherewithal to whip out my phone and make a recording. She thought of me, I guess, when she heard that. And I was whatever, either way, it ended up at Who's That Noisy. I think it's wonderful. And it's it's also an interesting sound to me because it represents the fact that that child survived in a situation where 50 years ago, they probably wouldn't have, which makes me happy for science and modern medicine and critical thinking. And Randi and Carl Sagan and so many other people.

New Noisy (1:10:05)

J: So anyway, I have a new Noisy this week. The sound was sent in by-

C: Wait, wait, Jay.

J: Yeah?

C: Before you tell that Noisy, are you going to like what? Do we get to know why a preemie baby sounds like an animal? Why is it so different at 30 weeks versus 34 weeks?

J: Well, I mean, Steve could probably answer better than me. I did think about that. And I'm just assuming it's because the the biology is so much smaller. There's a really big difference between a 30 year old, 30 week old baby.

S: Huge difference.

C: So it's literally that their vocal cords are tiny?

S: It's small and weak. And remember, it's breathing. The lungs haven't fully formed at that point. That's right on the verge of them being able to breathe at all. Their ability to make surfactant is like just coming online at that point in time. And sometimes they have to provide it for the for the preemie, if they're really premature. So, yeah, just a really, really just not fully developed respiratory system.

C: Sweet thing.

J: All right. A listener named Devin sent in this week's Noisy. This one is very cool. Take a listen.

[_short_vague_description_of_Noisy]

I love this Noisy so much. I love this Noisy. And when you find out what it is, it's just a fun sound. And you're and I think you'll really like the way it was created. And that's what I want you to tell me. Don't don't name the style of music, please. Tell me how was it specifically created? Like what is doing this? Right. Just either or you don't. But take a guess. You could email me at WTN@theskepticsguide.org with guesses and any cool noises that you heard.

Questions/Emails/Corrections/Follow-ups

Correction #1: Superconductors and Computers (1:12:16)

S: All right. A couple of quick emails. We have to do a correction from our discussion of the room temperature superconductors. Jay, you mentioned the fact that this would keep computers from heating up. And about 30,000 people emailed us to point out that's not true, right? That computers that the heat generated by computers is coming largely from just to oversimplify the fact that they're using semiconductors. And when they changing the information for flipping the gates or whatever, however they refer to it, generates some heat. And that's sort of unavoidable in the design of the computers themselves. And there's like no part of the computer that you would make a superconductor that would keep that from happening.

J: Yeah, that was definitely just a gap in my knowledge. I have no excuse. And I did beat myself in the bathroom before the show to get his penance for making this mistake. I'm sorry.

S: Yeah, I think we were thinking of electronics in general, which it is true. And we extrapolated to computers without really thinking it through. And then once they said, oh, yeah, yeah, of course, semiconductor, right. You know, but yeah, it's just it was like not. It was just one of those off the cuff comments. That is usually where we get in trouble. Yeah. But it is always a good opportunity to learn. It's always a good opportunity to learn and to point out, in this case, how computers work, or at least a very, very quick point about it.

Question #1: Beef and Climate Change (1:13:50)

You have talked about the destruction of habitats and how biodiversity is going down because of this. Isn't one of the biggest contributors the demand for meat, and especially beef, because many acres of rain forest get burned down to plant soy and corn to feed livestock? Wouldn't phasing out meat consumption be the "low-hanging fruit" regarding biodiversity and climate change? I think grass-fed cattle is carbon neutral, but what percentage of all the beef consumed is that? We can talk a lot about the missing political will to change things or about greedy corporations, but in my opinion it has to start with the consumer.

– Andreas Kleim, Germany

S: All right. And we got this other question. We don't have that much time for the for the Q&A. So I wanted to just do a couple of quick ones. A question comes from Andreas Klein from Germany. And Andreas writes, "You have talked about the destruction of habitats and how biodiversity is going down because of this. Is it one of the biggest contributors, the demand for meat and especially beef, because many acres of rainforests get burned down to plant soy and corn to feed livestock? Wouldn't phasing out meat consumption be the low hanging fruit regarding biodiversity and climate change? I think grass fed cattle is carbon neutral. But what is the percentage of all the beef consumed? Is that we can talk a lot about the missing political will to change things or greedy corporations. But in my opinion, it has to start with the consumer." So I disagree about it having to start with the consumer, because I think that the problem with that's a trap, as Cara was pointing out, the corporations are happy. They're happy to have to focus on the consumer because it takes the onus off of them. And it's really you have to take a political, corporate and consumer approach sort of combined in one system. You can't just shift focus onto the consumer. But it doesn't mean that doesn't absolve consumers of responsibility. t just means it's more complicated than that. I do have a very specific answer to the to the to the question. I'm going to change the question a little bit. It's not just how much is grass fed, how what percentage of the calories that are fed beef or fed cows that we will turn into beef. What percentage of those calories comes from food that people could eat that's edible to people? Or what percentage comes from inedible sources? And the answer is, you guys want to throw out a guess before I give you the answer for one?

C: Probably a lot of it is.

E: Yeah, 90 percent.

S: Eighty six, very close. Eighty six percent of calories is from nonedible sources. And so that's partly grass. It's partly what they call silage or just the nonedible parts of crops. And so most of the calories that cows get are going to be from those sources. And then the grain part comes mostly from the finishing lot right before they're ready to go to market. They want to pack on those last 10 to 15 percent of calories. That's the high grade grain that they'll get. So think about that cows are actually a good way of converting nonedible calories into edible calories. And if we took those calories out of the system, they would have to come from somewhere, right? If you say, let's just get rid of all beef. OK, so that's now a lot of that's 86% of those calories were coming from nonedible sources that they will have to be replaced. You could argue that maybe not all of them need to be replaced because we eat too many calories. All right. Fair enough. But that's not certainly all of them. You could also argue that some parts of the world over consume beef.

C: Our part of the world.