SGU Episode 972

| This episode needs: proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 972 |

|---|

| February 24th 2024 |

"The subsurface ocean of Titan is most likely a non-habitable environment, meaning any hope of finding life in the icy world is dead in the water." [1] |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

CS: Chris Smith, British virologist, |

| Quote of the Week |

The spirit of Plato dies hard. We have been unable to escape the philosophical tradition that what we can see and measure in the real world is merely the superficial and imperfect representation of an underlying reality. |

Stephen Jay Gould, |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Eclipse 2024 reminders[edit]

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, February 21st, 2024, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening folks.

S: How's everyone doing this fine day?

B: Doing good.

C: Doing all right.

E: Not too shabby.

J: All right then.

C: Did the rain finally stop?

S: Yeah, we're finally in the middle of an actual winter with cold weather and snow and everything.

C: Really?

E: Yeah.

B: Fifteen degrees Fahrenheit this morning.

C: Ooh, yikes. We had like three days of nonstop rain after we already had those two intense storms. So more mudslides, more flooding.

E: I heard a lake formed in Death Valley.

C: I heard that too.

E: That's how much rain.

B: What?

E: Yeah.

C: And it's gone already.

E: Outstanding water for several days. Yes.

C: But it's crazy how like powerful the sun is here. I went outside this morning and everything was still really wet and I just let my dog out before recording and it's like almost bone dry outside already.

S: So last, two episodes ago, we were chatting about the eclipse coming up in April. And I wanted to clarify a few things that we said during the discussion. So Evan, you said that the old eclipse glasses or solar glasses may not work, right? That they may expire after a certain amount of time.

E: Yeah. The cheapo ones.

S: So we were questioned about that. So we looked it up to get all the details. And it turns out that what you're saying is true, but it's a little outdated in that in 2015, there was a requirement in the US at least to adhere to international standards in terms of making solar glasses or eclipse glasses. And those do not automatically expire, right? So you could use them theoretically forever. However, there's a big caveat to that. And a lot of sites point this out, is that that assumes they're in good condition, right? So if you packed them away and put them away somewhere safe, yes, you can take them out again four years later or whatever and they're still good. But if you threw them in a drawer somewhere and they're like scratched or damaged in any way, do not use them. So old glasses comes with a lot of caveats. It's only if you've kept them in good condition. Because even a little scratch, that could be-

E: A pinhole could do damage.

S: Yeah. It could do significant damage.

J: Oh, wow. I mean, they're cheap. Just get new ones at this point.

S: Yeah. Why risk it? Just get new ones.

E: Better safe than sorry.

C: And you'll also know if you go outside and put them on and look up, you'll see. That's the thing about eclipse. They're so obvious.

S: Oh, yeah.

C: The sky will be black if you're wearing eclipse glasses in the middle of the day. And the only way that you'll be able to see the sun is if you know where it is and you look straight at it in the glasses.

S: Anything other than looking directly at the sun is pure blackness.

C: Yeah.

S: Right. The other thing is we were talking about when you should use the eclipse glasses and we just made a couple of general comments. But there's a lot of details there too that I was finding out. So one is that, well, of course, I don't think this needs to be said, but we're going to say it anyway. You can never, ever look directly at the sun at any time, at any part of the eclipse. The only time is during total totality. That's the only time you can look directly at the sun is during totality. However, there's one nuance to that that's interesting. At the beginning and at the end of totality, there's the so-called diamond ring effect, right? Where you get a bright rim around the sun.

C: Almost like a little lens flare.

S: Yeah. And it lasts for one to two seconds. So the question is, is it safe to look at that without your solar eclipse glasses on? And like when you say, so here I've read multiple recommendations, but most of the like official recommendations from NASA or astronomy or whatever, they say you have the eclipse glasses on when the diamond ring thing happens. When that is done, then you can take the eclipse glasses off. And then at the end of the eclipse, as soon as you see the diamond ring effect, you have to put your solar glasses back on again.

C: But that part is really, like it takes the amount of time it takes to put glasses on or take them off for that to happen. I think the thing that we have to remember is we're talking about this as if people aren't going to know the difference. It's like, have you ever looked up when the sun was in the sky? Don't look at it. It hurts.

S: Oh, yeah.

E: And that's the reason why...

S: Here's the thing Cara, so this is why there's so much discussion about like, is it safe to look at an eclipse? So you're right. If you look at the sun, it's extremely bright and it's painful. And you know, are your pupils clamped on? You squint, you look away. You can't, you'd have to really try to stare into the sun long enough to burn your retinas. But when enough of the sun is covered, it's the total brightness isn't enough to cause pain or discomfort or to close down your pupils. But that little sliver of light is still bright enough to burn your retina. So that's the most dangerous time is when your protective reflexes aren't in place, but that rim of that crescent of sun is still bright enough to burn your retina. So you're just basically burning up little crescents in your retina while you're looking at the eclipse without that protective effect.

C: I get that. But I also like, I don't know, in my experience, it's not easy to look at the sun until it's in totality. It's a concerted effort. You are still squinting into the sun if you're trying to look at it with your naked eyes, which you should never do. There's a huge difference between a partial eclipse and a total eclipse. It's massive. And so I more say that not because it's like, of course, I think that that's all really, really good advice. I also think, gosh, I hope people already know not to look at the sun with their naked eyes. I say it mostly because a lot of people are really scared of like, when will I know when it's okay? And it's like, you'll know.

S: Yeah, you'll know. It's not subtle.

C: There's a massive difference. It's not something that you have to calculate. It's not something that you have to work out on paper. It's really clear and obvious when you're in partial and when you go into totality.

S: Right. But don't take the lack of pain during partial eclipses thinking it's okay. I can look at, oh, it's not hurting. I can look at that crescent of sun. No, you can't.

C: Right. Yeah. Never look at the sun.

C: Yeah, it will still burn your eyes. It will still burn your retina.

E: Oh, my gosh. Not a good idea. Nope.

S: Yeah. And if you want to risk the one or two seconds of watching the diamond ring, that's fine. Just be careful. Just know that it's very quick. And as soon as that crescent appears, you've got to look away and put your glasses back on or whatever. If you blow the timing, as somebody pointed out, it's like if you try to, at the beginning, if you try to take your glasses off before the diamond ring effect so you see it and you get a glare from the crescent sun, that could also spoil your viewing for a while.

C: It does. Yeah. It bleaches you a little bit. That's true.

S: Yeah. You're not going to be dark adapted.

C: Yeah. Just wear your glasses the whole time. You'll know when-

S: Except in full totality.

C: Yeah. You'll know when totality happens. It will get dark. The minute it gets dark, you can take them off.

E: You will see the stars. That's how dark it will get.

C: Maybe. Depending on where you live. Probably not in LA.

E: You will see the stars.

C: Oh, wait. There is no eclipse in LA.

E: No.

C: You might not in Dallas proper see the stars. You might.

E: No. You will. I think you will. Why wouldn't you?

C: Because of the light pollution.

S: Well, the lights won't be on.

E: But will it illuminate during the day? The streetlights, they're not going to turn the streetlights on all of a sudden.

C: No, but there's a shitload of light pollution all the time. Trust me. If you can't see the stars in a nice clear night in Dallas, you're probably not going to see them in the middle of the day during an eclipse. here's a ton of light pollution.

S: That's interesting. Yeah.

B: There's one star I'm going to see, and I'll be looking at it.

C: Yeah. Well, and you are going to see stars. I mean, I'm just saying it's not going to be like the Milky Way. Don't expect during a total solar eclipse for the sky to suddenly look like Death Valley.

S: It's not going to be a dark sky viewing event.

C: Yeah. And also, there's still light all around the horizon. So like you might see a couple stars if you're in a place where it's relatively easy to see stars.

B: Oh, interesting. Yeah.

C: But it's not like the sky's-

E: Saw stars in Oregon. That's for sure.

C: Yeah. But Oregon is a pretty dark sky. Like there are parts of Oregon that are really dark. I was at least kind of out in the middle of nowhere. Were you also?

E: Yes. Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

C: Most people probably won't be for this. Some people will be along the path, but people who are going to like major metropolitan areas for it.

E: We're in a metropolitan area, I suppose. Yeah. Interesting. I don't know. I've never been in this environment, a metropolitan area during an eclipse. This will be a first.

C: I hear people cheering and stuff. It's really cool.

E: Oh, it's going to be amazing. It's going to be so good. Indescribable.

S: All right, guys. Let's go on with our news items.

News Items[edit]

Pesticides in Oats (9:07)[edit]

S: Have you guys heard all the hubbub about the pesticides in like oatmeal and oat products and Cheerios?

J: Yes.

E: Oh, I read something about that recently.

C: I thought I read something about like-

E: Yeah, terrible chemicals.

C: -lead or iron, not pesticides. Am I wrong?

B: The study doesn't bear that out, does it?

S: So there was a study published by the Environmental Working Group, right? Who is, in my opinion, kind of a... They're an advocacy group, not an objective scientific group. And they tend to always sort of over call the risk of toxicity, you know? So I always like it's... That's a red flag for me if the EWG is involved. So they did a study looking at the levels of a specific pesticide called chlormequat in oat-based products in the United States and in urine samples collected from people in the United States from 2017, 2018 to 2022, and then 2023, those three time periods. Why did they do this? So chlormequat is technically a pesticide because it's an herbicide. And what it does is it reduces the growth of the long stem of certain crops, right? So they don't grow as tall. And that helps in a couple of ways. It reduces the risk that the stalk will bend over or break, and it makes it easier to harvest as well, right? Without affecting, adversely affecting the thing you're trying to harvest, right? The rest of the crop. In the United States presently, it's approved for use in ornamental plants, but not food crops. In the European Union, it's approved for use in food crops like oats. In 2018, the U.S. changed their regulations allowing for the import of grains from the EU that were grown with chlormequat. So we still don't use it in the U.S., but now we are allowing the import of food from the EU that did use it. I was interested in that out of the gate because generally speaking, the EU has stricter regulations and restrictions than the U.S. does. So this was odd that it was flipped. But anyway, so they were measuring, okay, well, is it being found in U.S. food and is it being found in the urine of people in the U.S.? So even before you do the study, the answer is, of course it is because we went from not having it in the food stream to having it in the food stream. So the result seems pretty obvious. But okay, fine. They wanted to see confirm that and see how much. And they found pretty much exactly what they were looking for. Yes, many of the products that they tested, they said all but two of 25 conventional oat-based products had detectable levels of chlormequat in it and with a range of non-detectable to 291 micrograms per kilogram. And they found concentrations in the urine of subjects as well. And that concentration increased from 2018 to 2023 because, of course, it did. And now we're importing oats from Europe that were grown using it. So they basically used this as an opportunity to advocate against the U.S. loosening up the restrictions on chlormequat, which they're considering doing, and saying if you want to avoid it, you can eat organic. You could buy organic stuff, right? So they're shilling for the organic industry and they're always about like more restrictions on anything chemical used in agriculture. So the reporting on this has been horrible because they're basically buying the Environmental Working Groups' framing of this hook, line, and sinker. For example, a headline from a CBS News report, Pesticides Linked to Reproductive Issues Found in Cheerios, Quaker Oats, and Other Oat-Based Food. And then you read the article and it's all just quoting from the Environmental Working Group and without any real context. My first question was, what? What do you guys think? When you hear this story, what's your first question?

E: There are trace amounts of all kinds of things in our food. How dangerous is the amount of this?

S: What's the amount? What's the dose?

C: Yeah. What's the dose.

B: What did they find?

C: And what's the outcome of that dose? Like what should we expect from that dose?

S: Exactly. So there are established safety limits. You know, the U.S. has its safety limit. The European Union has its safety limit. In the U.S., the safety limit is 0.05 milligrams per kilogram body weight per day. And in the European Food Safety Authority, it's 0.4 milligrams per kilogram per body weight per day. So you notice anything about the units so far that I've thrown out there?

J: Or their kilograms, they're not-

E: Grams. We're talking metric.

S: So the amount they're detecting in the oats is in the micrograms per kilogram (µg/kg).

B: Yeah. That's a millionth of a gram, right?

S: And the safety limits are in the milligrams per kilogram.

B: Thousandth of a gram.

C: So that's three. Yeah. That's three decimals away.

S: That's three orders of magnitude. And they say in the study that the amounts that we're detecting are several orders of magnitude below the established safety limits. Yeah. Because they are. And, of course, none of the reporting mentions this, right? I actually did a fun calculation. I calculated how many kilograms of oats you would have to eat every day in order to get up to the lower end of the limit of the safety levels the safety regulation.

J: Can I guess?

S: Yeah. What do you think?

J: What measurement are you using?

S: How many kilograms of oats would you need to eat to get enough chloroquine to exceed the lower limit of the safety levels?

E: And a kilogram is, what, 2.2 pounds?

S: Yeah.

J: Okay.

B: A centillion tons.

J: I'd say 10 pounds a day.

S: Ten pounds a day.

E: Ten pounds. That's about, what, four kilos?

S: Four kilos a day.

E: 4.3 kilos.

C: And you said this is for – you calculated it for what, like rolled oats? Did you also calculate it for something like oatmeal? Is it somehow concentrated?

S: I used the highest level that they reported.

C: No, I know what I'm saying in terms – I mean the delivery method because some people drink oat milk. I don't know if it's like – is the concentration higher or lower in something like –

S: Well, let's say dry oats because I'm just giving you the levels that they detected like in Cheerios or in Quaker Oats or whatever.

C: All right. So you're saying how many like – how many oats, like actual like bowls of oatmeal?

S: Yeah. In kilograms.

E: But in kilograms.

C: In kilograms.

E: 2.2 pounds.

S: Because that's what they needed.

E: It's at least one kilogram. Let's say 12 kilograms. 12 kilos.

C: Yeah. 10 or 12. I don't know.

S: 85,000 kilograms.

E: Oh my gosh. It's even worse.

C: OK. So it doesn't matter.

S: All your questions are –

E: We're in homeopathy territory for all intents and purposes.

S: Exactly.

E: Yeah.

S: We're at homeopathic doses of chlormequat.

E: Yeah, right. Avogadro here.

S: Now, here's the thing.

J: You have to eat that every day?

S: Every day. In the study –

E: Every day.

S: In the study –

E: For what, like three months, right?

S: They say – no, it's every day. They say, now, we know that these urine levels that we're detecting probably represent ongoing exposure because chloroquine is rapidly eliminated from the body through the urine.

E: There you go. Kidneys. Thank you.

S: So this isn't something that built up over time. They must be consuming this every day. It's like, yeah. It's rapidly eliminated from your body through the kidneys. Think about that. That also means that you would have to eat those 85,000 kilograms of oats every single day. Right? And the moment you stop doing that, your body would clear it out of your system. I mean, it's just –

E: It brings it into the implausibility category.

S: That's the several orders. So again, it's several orders of magnitude.

E: Impossible.

C: Yeah, I'd say impossible.

S: It's impossible. Obviously, it's impossible. But not only that, but when the EU and the EPA, whatever, when they establish safety limits, they're already going one or two orders of magnitude below the lowest dose that was shown to cause toxicity. Right?

C: Always?

S: Yeah. They take like – Yeah. They use the data, usually animal data. So at this dose, we start to see adverse health effects. So let's go one or two orders of magnitude below that, and that's where we'll set our safety limit. That's standard procedure. So then you go three orders of magnitude further below that.

C: I always wondered about the politics of that for something like lead back in the day. I would have assumed they would have erred in the other direction, sadly. I'd be wrong.

S: No, that's the standard procedure. Go at least an order of magnitude below where you start to see adverse effects. So no one mentioned this. Then they say – Also, the toxicity that they're talking about, like the reproductive issues, that's only in animals. Never been shown in humans.

C: Yeah.

S: And it's shown in animals at massive doses. Again, at these kinds of ridiculous doses, right? Of course, because that's where you set the – That's how the safety limits were set. So it's ridiculous.

C: Because you can probably feed a farm animal pounds and pounds of oats, but like we don't do that.

S: It's still fine. It's 80,000 kilograms, Cara.

C: That's great.

S: It's ridiculous. The whole thing is silly. It's silly.

E: It's like a silo of oats or something, right? I mean how –

C: Is there an animal that can eat that much?

S: So what's the – The only thing I could see that the purpose of this whole thing is just to create a round of fear mongering in the press to lobby against the U.S. changing regulations to shill for organic food. When I wrote about it on Science Based Medicine in the comments, someone pointed out, it's also – Another thing, whether this is their purpose or not, it also accomplishes the goal of leveling the playing field between traditional or standard agriculture and organic. Because if you basically deprive agriculture of using all of the science and technology that we have available, then it narrows the benefit that the increased productivity and cost effectiveness and land use and all that, that standard agriculture has above organic agriculture. It's like you can't use GMOs. You can't benefit from GMOs because they're trying to ban it because then that narrows the gap of the advantage over organic, right? So it also creates the – Well, just eat organic just to be safe. You know, because then – Just to be safe.

E: Be extra safe.

S: Yeah. It's absolutely ridiculous. This is why I have a massive problem with the Environmental Working Group because they pull this kind of shit all the time.

E: And the media is, of course, willing to go along on the ride.

S: Yeah. They didn't want to spend – Whatever. Because this is being reported probably by people who are not science journalists and they're quoting experts, right? So they think their job is done. They didn't take the 10 minutes it would take to ask the most basic question. It's like, well, they just quote somebody from the EPA that's saying this is below safety limits, right? And then they quote somebody from Quaker Road saying we follow all regulations, which always sounds like – Even though it's true.

C: Yeah, it sounds sketchy as hell.

S: It sounds sketchy as hell because – Yeah, because –

J: We follow all regulations.

E: It's designed to meet legal scrutinies, right? Anything that can be used against them in court.

S: It sounds like boilerplate denial, right? And rather than saying-

E: Yeah, boiler speak.

S: Yeah, we asked an independent scientist to tell us what's going on here and put it into some context for it, and they told us you'd have to eat 80,000 kilograms every day for this to be of any concern. Whatever.

C: Right. Which we don't recommend doing anyway.

S: – Which we don't recommend. Yeah, right. By the way, people-

C: Kill you. For other reasons.

E: You would die of a million other things before you died of this toxicity if you consumed that much.

S: The chlormequat would be the least of your problems, yeah.

C: I think you would explode, like, all of your organs.

J: I'm getting gassy just talking about this.

AI Video (21:36)[edit]

S: All right, Jay, tell us about the AI and video. We've been talking about this.

B: Oh, boy.

J: So you guys have heard of OpenAI, right? Everybody has. Well, they recently introduced the next digital demon called Sora. It's pretty Bob, AI it's good and scary at the same time. So the product is called Sora, S-O-R-A, and this is a sophisticated artificial intelligence system that is designed to convert text, similar to, like, DALL-E or MidJourney. It converts text into photorealistic video, not an image, a video, a 60-second video. This is a massive milestone, and it's another leap in AI technology, and it's a huge step forward for OpenAI's technology suite. Other companies have text-to-video, and many others are working on it, but Sora looks to be way ahead of the rest of them. I was doing some research. There really isn't anything to see from any other companies. There's a lot of chatter about this company's working on this, this company's working on that, but this seems to be the first one to make it to market that has a photorealistic quality. So, of course, there's a mix of excitement for the potential to enhance the creative space, and we can produce educational content there's lots of ways it could be used, but there are also a huge list of legitimate concerns over the implications for misinformation, disinformation, and particularly during this critical election period that's going to be happening over the next year. So, Sora is unique in that it can generate videos, like I said, up to 60 seconds in length from simple text instructions or a combination of text and images. I know you guys were talking about this on the live stream last Friday. Cara, I don't know if you have, but I could send you a link just so you could take a look at what types of video that this can produce. It's remarkable.

B: Remarkable.

J: The videos that I saw, remarkable. One of the best ones I saw was a woman walking down a city street that looks like a neon-lit Tokyo. Just, I would have no reason to think it wasn't real. There was just not one indication in there to my eyes that it wasn't real. The human faces, the movement, excellent. Like one detail I saw where there was somebody that was carrying a shopping bag, and it was kind of like bouncing off their leg and moving erratically like a shopping bag would if you're hitting it with your leg as you're walking, like that level of quality. So, of course, we really won't know the ins and outs until we can use the product ourselves, but they're showing us, of course, the most impactful videos that they came up with. But there's no reason to think that in a short matter of time they're going to open this up and we're all going to be using it and it's going to be easy to use. I mean, they show you the prompts, the textual prompts.

S: Yeah, they show you the prompt.

J: And a typical prompt would be like what I wrote. A woman walking down a city street in Tokyo with lots of neon lights. You know, that's all it would take to generate this 60-second video. There's a major creative problem that I think we should discuss very briefly. Steve and I have the most experience with this. This problem with current image creation software. I've used DALI. I've used MidJourney. And the thing that they can't do well right now is they can't handle specific instructions. Steve and I were just talking about Steve was making an image. He was making for a tabletop game that he was playing and he was trying to get a gem to appear in the middle of a medieval shield. And he just couldn't get the software to do it. And the thing is, it makes you an image and you can't say, take this image that you just made and add a gem in the center of the shield because it'll just generate a brand new shield. It doesn't like follow. So you're kind of starting from scratch every time you go and you just, you modify the text that you're using to kind of get you in the area where you want it to be. But there is no specific instructions here to change minute details. So if Sora has the same limitation, which I guarantee you it will have, its usefulness in the beginning are going to suffer quite a bit because you can't say, have the woman walk a little faster. You probably won't be able to do things like that. And that's if people are going to be using this to make like, movies and stuff, which eventually they will, that functionality I guarantee you just won't be there in the very beginnings of this because again the technology is young. It doesn't get more young than this.

S: But that seems like an easily fixable problem though.

J: Yeah. I mean, that's just from a creative standpoint. I thought that would be an interesting thing to throw out there because we have a lot of experience working with AI image generators and like that's a massive flaw that they all have. So now let's get into what I think are the big warning signs here and what I'm worried about and what the experts are actually saying. So this technology will suddenly put us into a world where we just can't trust anything that we see and very soon we can't hear anymore. And once they marry the ability to fake voices, which we could do very well right now, when they marry that to the video footage, people are going to be able to generate pretty much anything that they want and we're not going to know what's real and what's not real. Now they're saying at OpenAI they're taking caution and they have a group called the Red Team that's testing the AI models for safeguards against misuse. This sounds great. This testing phase involves experts and misinformation, hateful content, bias and their goal is to identify and mitigate potential avenues for abuse. That's great and I really am glad that they're doing that. But people will find a way and this is just one company. What if a company comes up with this technology a year from now and they're in another country that doesn't have regulations and that will happen. So it's great that OpenAI is doing this and I just don't see the world getting on the legislation aspect of this so quickly that companies are not going to be able to do the thing that we're all afraid of, which is putting stuff out there and we no longer know what reality is. So here's a list that I gathered from a few different people like Oren Etzioni, who is the founding CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. This person has played a significant role in the development of ethical consensus for artificial intelligence technologies. So I borrowed some of his items. I was reading through a lot of different people's list of like these are the potential threats that we're putting up against. So here's the list. Proliferation of deepfakes, right? Sora could significantly enhance the ability to create deepfake videos, making it difficult for the average person to distinguish between what's real and what's not real. That's big. Misinformation and disinformation, right? This tool could be used to generate fake news, misleading content. I mean, I think this is the first thing people are going to do with it, is just use it to make content that's not true, but seemingly real. Security concerns, right? There's high quality video. Deepfakes could be used for malicious purposes like impersonating people, fraud, targeting individuals and institutions. It has threats to creative industries. We've talked about this, but now that people will be able to make video, I would say in a handful of years, people are going to be making movies on these platforms. So that's a big shift. It's going to affect a lot of people with a lot of copyright issues. It's just going to explode. The word explode is not big enough, but it will be an explosion of copyright issues, job losses, a change to culture. Very, very powerful, what this video capability is going to be. It's going to introduce a lot of problems. There's ethical and moral concerns, the ease of creating realistic video content. People are going to be able to make porn and all sorts of stuff like that. It's putting celebrity faces on porn and things like that. It's going to happen.

S: Unless they build in protections.

J: Sure. But like I said, Steve, OpenAI will probably not be a company that will let that happen with their stuff. But what about the 30 other companies that are going to be able to do this? So there's going to be regulatory challenges. Like I was saying, right now the framework to do this framework to deal with AI is loose. It's not good. And the government is not moving. U.S. government, I'm talking about, not moving fast enough. And to be quite honest with you, the people that are making decisions don't really grasp this technology. They're not the right people to make the decision. We need professionals who really understand this stuff to help form the regulation. I mean, this list just keeps going on. I have a lot more. I can't even get to all of it here. There's just a lot of reasons why we have to be very, very careful with this. And no matter what, it's going to change our culture. And it's going to change a lot of things. Unpredictable things, as we always say. Like every time we can get an idea of what something can do, there's a hundred things that we can't predict. So that said, I do think that there could be an incredible benefit for creativity. It's going to allow people who don't have the ability to make video, to make lifelike video and a lot of creation can happen. That's all wonderful. And I think if it was limited to that use, there could be a lot of really cool stuff that comes out of it. But the potential here for danger is extraordinary. So I am like, I don't even know if I'm enthusiastic about this. I think it's too early for me to just say, I think this is great. Let's lean into it. I think this is scary and we need to be very cautious. And I think we all have to be prepared for what's going to happen in the next couple of years.

S: Yeah. I'm excited about it and cautious. I think those two things are not usually exclusive. I mean, I'd love to get my hands on it. And again, I'd love to see where it's going to be in four or five years. I mean, I think the big thing is the ability to iterate, like the ability to say, I want this exact video that you're showing me but make this one change and have that happen, you know. But it's interesting also looking at all, I looked at every video that they put up on Sora and having a lot of experience with, say, MidJourney, they're all in the same ways. When they're constructing the images or the video, it's like they don't quite get the physics right all the time or, like, things don't relate to each other in a realistic way all the time. You know, that's something they definitely have to work on. Often there's a tell in the video that this is AI.

J: That's temporary, Steve. You know?

S: Yeah, I know. I know. But I'm interested to see how long it's going to take before somebody makes a movie with this. But here's the one thing that we have to mention, though, Jay, that these videos don't have sound. So the people in the videos are not talking. And that is often the giveaway for an AI. Like, that's where you get into the uncanny valley as soon as they move their mouth.

E: Even if, yeah, if you were to put voice over it, you would, it's not the same.

J: Yeah, I know. And again, like, that's the first couple of years, that will be the thing that we notice. But then it's just not going to be a problem eventually. They'll solve that.

E: Will it ever achieve that?

S: Absolutely.

E: In our lifetime?

S: I think so. Oh, yeah.

B: Oh, yeah.

J: Oh, absolutely. I mean, I...

B: My God, in 20 years, can you imagine this technology?

J: I would imagine in five years, we're going to be shocked at how far it's come. These companies are spending more and more money investing in AI. Like, it's ramping up big time. You know, more and more companies are doing it.

S: Let me play devil's advocate on that prediction for a little bit because the other thing that we've run into, guys, and we've personally been there many times with similar...

B: The last 5%.

S: That last 5% sometimes takes as long as the first 95%.

B: Yeah.

S: And that's what we're seeing now. Like, this is really impressive and we're just assuming that that last 5% will be quick, but it may not be. Like, with speech recognition, like, they got to the 95% level and it was very impressive. And like, oh, man, just in a couple of years we're going to... You know, this will be off the hook. And it took 20 years, basically, to get that last 5%. Now it's fine, but it took a lot longer than we initially thought. Same thing with self-driving cars. They got 95% there.

B: Same thing.

S: And that last few percent, which is all... makes all the difference, right?

C: But there's also something interesting here because I think that there's... You know, when you talk about, like, self-driving cars or the speech recognition, which is maybe a better example, we're talking about something being made that then has to be adaptive into a structured and regulated system. Whereas, when we're talking about using AI to, like, make films, for example, yes, that last 5% to make a Hollywood blockbuster might not be there. But because of the Internet and social media, I wonder how good is good enough for certain applications.

S: You're right.

E: Yeah, if you're just trying to trick people, you don't need 30 minutes. You need 30 seconds.

C: Right. Like, we need a self-driving car on the road. But we don't need an Internet film to be perfect for, like, to trick somebody on, like, Instagram.

S: Yeah, that's a good point, Cara, but I was responding specifically to what Jay was saying about where it's gonna be.

C: Right.

S: But, like, Midjourney right now is great for personal use for things. Like, I use it, Jay and I are using it for our gaming because it doesn't matter if it's effed up. You know, it doesn't matter if it's not quite right. It's cool. It's conveying what we want it to convey. You know, and it's like, don't worry about that little ditzel. Who cares? But, yeah, if you're trying to put out a film, or if you're trying to be photorealistic, like, to fool people, then that's a, you're setting a specific bar.

C: And also, where's the bar for, like, who you're trying to fool? Because there's always gonna be, like, some people you'll be able to fool even if it's, even if the bar is relatively low. And then there's certain critical people who you won't be able to fool.

S: I think, I think, like, right now, if you wanted to put out one of these fake videos of a celebrity, a known person, talking and saying something that they didn't say and you paired it with the speech, simulator as well, I don't think we're at the point where you wouldn't be able to tell the difference. I think it would be pretty obvious.

C: Yeah, we're probably not. But I would also say we might be at a point right now where even a slap, a hap-hazard job of some sort of political disinformation video still convinces enough people to move the needle.

S: It moves the needle, right?

C: Yeah.

E: That's all you gotta do. You just gotta put your thumb on the scale. That's all you gotta do.

B: How about this?

C: Because there's always gonna be some credulous people.

B: Yeah, for sure. Or how about this? Somebody's video is recorded and it's legit. It's reality. And they say, oh no, that never happened.

C: Plausible deniability.

B: Well no, it's not a fake. it's absolutely real. A lot of people will believe that, oh yeah, you didn't really do that.

C: Right, to get out of like a sex scandal or some racist thing they said in the past and say, oh, somebody just made that up. Oh, fascinating.

B: That's another angle, yep.

C: Oof.

University Rankings Flawed (36:56)[edit]

S: All right, Cara, tell us about university rankings.

C: Yeah, so this is an interesting article that I came across in both The Conversation and also, interestingly, in FizOrg. Which is about are university rankings scientific? Are they helpful? Are they harmful? And, I didn't realize, but an entire panel was actually convened. It's called the United Nations University's International Institute for Global Health. They have something called the Independent Expert Group, which convened to actually look in independently to the claims made by these global university ranking systems to see, A, are they valid? B, are they helpful or harmful? And I think I went in a little bit skeptical, like, eh, I don't really buy it. There's probably too many variables and it's probably a little bit biased, but I didn't realize that there's kind of a lot wrong here. So, they, in their big kind of position paper, make multiple claims. The first one being that university rankings are just conceptually invalid, just like as a concept it's not going to make sense to rank universities because there are too many factors and each different ranking organization looks at those factors differently and they're not transparent about how they rate them. And so, they looked at the four main ranking companies and I use the word company intentionally because these are all for profit systems and they are, I can't say this one, so I'm going to call it QS, it's a British one, Quacquarelli Symonds, I'm not sure how you pronounce it, so I'm going to call that QS, the Times Higher Education, which is shortened to THE, T-H-E, the Shanghai Ranking System. That one is in China. And then the US News and World Report which most of our American listeners would be more used to hearing. The first two are British. And so they looked across those four ranking systems and said, first of all, there's a conceptual problem with rankings, it just doesn't make sense to put all these different institutions of higher education into one big bucket and then put them in some sort of rank order. They also concluded that the methods that they used by these different systems are usually really opaque. And some of them are actually blatantly invalid. So they're saying, hey, listen, if we were peer-reviewing this, if this was something that was up to peer review muster, so why are we able to kind of societally use these rankings to try and guide behaviour? A few more big takeaways. They tend to be biased towards research institutions, towards STEM subjects, so science, technology, engineering, and mathematics and away from things like political science or liberal arts. And they tend to be biased towards English speaking universities and scholars. They also make an important point, and they've had some spin-off papers about this, about how they tend to be colonial in nature. So what ends up happening is you have these national, global, and regional, I said those in a weird order, let's try that again, regional, national, and global inequities that have existed because of things like structural racism, and then you consistently rank as the highest the only the institutions that have the most financial backing and so what you do is you just like deepen those inequities, right? Because now all of a sudden you're saying, okay, this is the best school, this is where all the funding should go, and it just gets driven more and more up. And then just a couple of more things, they also said that they believe that these rankings undermine the development of higher education as a sector because instead of sort of fostering shared responsibility, they're incentivizing these sort of like self-serving short-term stances for universities to take, like what can do to go up on the rank this year instead of saying what can I do for education globally as a part of that also just that short-term ranking cycle is a really big problem. They're thinking more short-sightedly. There's a few more other issues that they talked about. Oh, this one really gets to me. Apparently, there's this massive conflict of interest that takes place because these ranking systems are developed and utilized by for-profit companies and they claim to be impartial about their judgements but then they sell advertising and performance-related products like consulting services to the very universities that they're ranking. So they'll be like you want to get higher on the list we can teach you how to do that. And that's a blatant conflict of interest. There are a lot of problems here and their big takeaway is probably we shouldn't be doing this. Probably university should not be engaging in the ranking system. Consumers, individuals who are looking to where am going to put research money or where am going to apply to university or all these different considerations that you're going to have about higher education should not be looking at these different ranking systems to make a decision. Also it doesn't make sense because it's like, okay, how can you say that so and so is the best school at all things for all people at all times? Like there are just different strengths and each individual choice should be tailored to your interests and to what your needs are. They also encourage trying to come up with alternative versions. Apparently there are some ranking systems out there that are less flawed and then they recommend just disengaging from these practices that they deem to be "extractive, exploitative and non-transparent". So yeah, apparently it's not good. University rankings not good.

S: I know like in my institution, everyone's always complaining about the ranking, but then also trying to game them as well.

C: Exactly.

S: These are terrible but we got to do this otherwise- and we also, we all recognize their crap. They don't really reflect what we think about, the relative academic value or whatever of different institutions. Obviously we're biased, we're all biased for our own institution but even still it's like really that's how they the rankings like don't even make sense.

C: They don't make sense and also they're apparently not very ob- even the the data that they use is oftentimes not very objective. Like a lot of the data, let me see if can find it. Like 50% of the score of the QS world ranking comes from a survey of subjective opinions by anonymous people. The Times it's 33% and the US News Best Global Universities Ranking, 25% of their entire ranking score just comes from anonymous people being like, I like that one better.

S: Yeah, right.

C: Like what?

S: It's the same with hospitals, again, same kind of complaint. And the thing is, any time you have any kind of ranking system like this, especially if there is any subjectivity to it, or like it requires a lot of knowledge. If you're not a professional, how are you supposed to be evaluating it? It's just an invitation to game the system, right?

C: Absolutely. And then it creates incentive to prioritize gaming the system over improving outcomes. And that's really dangerous. It's the classic conundrum of like the GRE just teaching students how to be good at test taking.

S: Exactly.

C: Or how to be good at taking just that test. It doesn't actually give you any indicator of how well somebody's going to do in higher education and so-

S: Here's a real scary example from medicine. If you rank surgeons by or you just tell that like disclosed to the public this is how many people die within 10 days of getting surgery by this surgeon, or at this hospital. So you would think oh, that's really useful information. We want to know that. Yeah, but different surgeons will specialize in different procedures and whatever. And what you're basically doing is incentivizing surgeons not to operate on risky patients.

C: Yeah and not to do high risk procedures at all.

S: And not to do high risk procedures. They don't want to ruin their numbers, right? Or for hospitals not to do it. It's like, no, we don't, we're not going to, so yeah, so you leave patients out to dry because the surgeons or the hospitals or whoever don't want to ruin their numbers. You know? It must say that I'm not accusing that of happening in a place specific, but that's the concern.

C: No, but that's a great example of a real life outcome that could happen.

Mewing and Looksmaxxing (47:15)[edit]

S: All right, Evan, I don't know what these words are. Mewing?

C: Mewing?

S: Yeah, it looks maxing. I mean I'm assuming you're not talking about cats.

E: No, we're definitely not talking about cats.

C: Evan, please tell me you watch the doc.

E: I watched the documentary. Yes, I did. We'll get to that.

C: Okay.

E: We'll get to that. But let me start with this. You know like to start things, take you back a little bit in time. A long time ago, like the 1980s a man on television once said "you look marvellous". And it's better to look good than to feel good. Well now fast forward to 2024 and you get articles like the one I read in the Guardian with a title "From bone smashing to chin extensions: how ‘looksmaxxing’ is reshaping young men’s faces. Looksmaxxing, what is it? An online community of people seeking to enhance their faces. Mostly men, but it's not restricted to men. There are women who participate in this as well. It includes things that people can, well, they can make some easy changes and with little effort and risk. And those types of changes are referred to as soft maxing. Those are tweaks, like changing the style of your hair, using skin care remedies, certain diets or exercise regimes.

B: Botox soft?

E: Not that one doesn't fall into the soft maxing category. You know again soft maxing you know kind of the easy reasonable stuff that almost anyone can do without, again, much if at all risk. But you get to the more aggressive approaches to looksmaxxing and that's known as hard maxing here's where the Botox injections come in Bob. But it's not just that. And something else called mewing. Mewing. Yeah. That's not something, Steve. I've never... Did you hear of mewing before brought it up this week. No hadn't either. Cara had you, you saw the documentary.

C: Yeah, I heard about it in the doc though.

E: Okay in the doc. What the hell is mewing? All right, mewing, here it is, named after John Mew, M.E.W. An orthodontist from Kent in the United Kingdom. He's still alive today. He's in his 90s. He and his son are the subject of a one episode documentary on Netflix running right now called Open Wide. So you can go watch it there. John Mew is the founder of a technique he calls orthotropics. Orthotropics is a branch of dentistry that specializes in treating malocclusion by guiding the growth of the facial bones and correcting the oral environment. I'm taking this from one of their websites. This treatment creates more space for the teeth and tongue. The main focus of this approach is to correct a patient's oral and head posture. They use a variety of different removable appliances that can help with expansion and also correct posture. A malocclusion is a misalignment between the upper and lower teeth so that they don't fit together correctly when chewing or biting. And that condition can be described as common terms like crowded teeth, crooked teeth, protruding teeth, irregular bite, crossbite, overbite, underbite, those are some of the terms that are thrown about to describe it. It is considered controversial. Controversial alternative to things like braces and tooth extractions which is something know had done in the 1980s. I had two teeth extracted and braces slept.

S: Evan this is a controversial whether or not it works?

E: Yes, that is correct. You know why? Because there's no science backing it.

C: I think it's controversial for a lot of reasons.

S: Yeah, but was just wondering if that was one of the reasons. They're not even sure it it actually works.

E: That's the main problem here. They have few and far between, very small, very selective studies that have been done, most of them either conducted by the Mews themselves, or people who were like, disciples or spin-offs, people who went to learn from the Mews and they kind of ran some things. So you've got these, studies that really have not been independently verified and there's a lot of problems with those particular studies.

B: But, well, Evan, is mewing related to looksmaxxing? Now that's a sentence I never thought I would ever say. But is there a relationship?

C: That's the main driving force, right?

E: Yeah, yeah, it is.

B: Well, if that's the case, then I think a before and after picture would be all you would really need to say, well, this actually made this person look better in my opinion so I mean how much evidence would-

S: The problem there the problem there the Bob is that they're probably doing multiple things and therefore it's hard to ascribe one thing to why they look better.

C: And also it's subjective and-

S: It's very subjective.

E: It's subjective.

C: And also, some of these pictures they do look better which is probably why they would been able to like keep doing this for so long. But what is it actually because of?

B: The picture in the article that that was in the group email on this, it showed a before and after of a kid. Now granted it was a three year difference so some of this difference is just growing up.

E: How do you determine the difference? Right.

S: Yeah Bob, it's growing, it's grooming. He's got a beard versus no beard.

B: Yeah. It's a dramatic difference and I would just like to, I'd like to know and I know it's probably hard, what exactly was done to achieve that effect because think the impact was impressive in that one picture which have no history of. Who knows? They could have even manipulated it, in many different ways.

S: And how cherry-picked was that.

B: Yeah. Well, that as well.

C: Evan, it takes, it's like a three-plus year process, isn't it?

E: It is an even longer if you're older.

C: Yeah. Yeah.

E: For younger people apparently it doesn't take as long. But you would have to go a very long time using this technique to possibly see some results.

B: How long would it take for me then?

S: You'll look great in the coffin.

E: Again, no real good studies on this, however, there is an orthodontist. His name's Kevin O'Brien. he runs what's called O'Brien's orthodontic blog. He's an emeritus professor of orthodontics at University of Manchester in the United Kingdom. He has been following this for many years and been blogging about it kind of regularly, especially as it pops up and he did one again kind of recently. It was last year and what he said in this particular blog post because he doesn't, again, he's of the position that no real good science to back this up and in fact some of the claims that are made by maybe not the Mews directly but some of their disciples and stuff including helping with your sleep apnea and helping with breathing and swallowing problems speech disorders, sinusitis, among other things. You know, it starts to kind of, they kind of lose control of the narrative in a sense, and then you start promoting this thing as being able to help you not only look better but also start impacting your health in various ways. But that aside. There was a recent, they call it an investigation, what it is, it's a master's thesis. So I guess it's an non-published study in a sense and what they did in this particular investigation they're ceiling it-

C: Well master's thesis should be published.

E: According to Kevin O'Brien, he reported recently on a study or a retrospective investigation is technically what this was, in which he says this, I came across a well-written MCS thesis from the University of Alberta, in which they analysed cephalometric radiographs of 102 consecutively treated patients. They took cephalograms before and after the active treatment. So that was the orthotropics. Then they compared those cases to a control group, 75 sets of records obtained from the AAOF cranio facial growth legacy and they tried to do as close a match of the of these sets of patients for things like, you know, age and sex and timing of records among other things. So they did their best, I guess, to try to get two things that could be as considered as close as possible. So you have one control group, and then you've got the orthotropics group. He says here, the authors of the thesis concluded, the treatment protocol may not be considered to have produced a clinically meaningful effect on skeletal and dental changes. And he said that and in his blog he said this is really one of the better analysis. It's not really a full-blown study but of the limited material that's out there this is one of the best if not the best so far.

S: And it's negative.

E: And so far it's negative. I also did speak with some other people about this. I spoke with Grant Ritchie recently, who's a skeptical dentist. He used to be on with science-based medicine among others. And he did watch the documentary as well and he also is familiar with this and he basically says this is kind of a problem with orthodontics in general. Not only this orthotropics don't have the studies to back up what it is they're claiming. This is true for a lot of branches or a lot of aspects of orthodontics. So the whole kind of industry in a sense can use improvements and more studies, better studies, and more investigation into these things to really figure out what works best. So that's kind of where we are in all of this. But mewing, yeah, so far it has not delivered the goods.

C: Didn't he lose his dental license?

E: Yes, he did. The Mew senior, he was stripped of his dental license because he was basically, if you watch the documentary you'll get sort of the tone of his attitude and stuff. He's definitely an outsider, he's there to upset the apple cart as the expression goes. And kind of, has very much his own way of doing things that are very contradictory to, established practices in the field. And he went so far astray they felt that was necessary they had to cut him loose.

C: Yeah. Because it's not just that he's like hey here's an untested thing that think works better he's literally like traditional orthodontics is not the way. Nobody should be getting braces. Everybody should be doing that.

E: Yeah, he absolutely slammed the whole industry and said that what they're doing, is a-

S: That's a huge red flag.

E: Big red flag. Yeah, big red flags. lot of red flags. So yeah, go watch it if you want to learn some more about it. But hey, a new term to throw into our skeptical lexicon mewing.

S: Yeah, don't buy the magic beans.

E: Right, right, and don't and don't be influenced by the one billion, yes, one billion references to mewing on Tik-Tock. A billion.

S: Don't be influenced by the influencers.

E: Exactly.

S: All right, thanks, Evan.

Titan Uninhabitable (58:39)[edit]

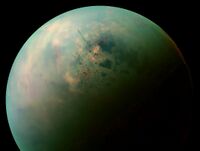

S: So Bob, tell me, what do you think? Could there be life on Saturn's Moon Titan.

B: Well, let's see. A new study claims that the mighty moon of Saturn, Titan, the most organic rich icy moon in the solar system, has vastly decreased chances for life than previously thought because it looks like the organic surface of the moon could have a lot of trouble getting to all the water deep below the ice. So the question is, how depressed should be about this? Let's see. So yes, reading the popular articles about the study was very disappointing. I've been convinced for many years that there's a really high chance that microbe-like life exists under the ice of some of the moons in our solar system. But reading this study actually made me less pissed than initially anticipated. So let's see what this is all about. This was a study published in the journal astrobiology, led by astrobiologist Catherine Niche. So let's start with Titan itself. Titan is kind of ridiculously special, I think, as far as the 150 or so known moons go in our solar system. It's bigger than our moon and by a lot. I think its diameter is like 50% longer, bigger and it's even bigger than Mercury than the planet Mercury which is really interesting. It's the only moon with a dense atmosphere and even better, did you know this? It's the only place in the solar system except for the Earth withstanding bodies of liquid. Lakes, rivers, seas, the whole panoply of liquid collections on Titan. Now that's that liquid isn't water though on its surface, not when the surface is like minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit or minus 179 Celsius. That's friggin cold. So there's no water. It's flowing methane and ethane. And so if you want great lakes filled with natural gas, Titan is the place to go. Now the atmosphere itself is interesting. It's mostly nitrogen like Earth's but it's also 5% methane with a few other lesser gases in there. Now these molecules split apart and they recombine as hydrocarbons and also often include other elements like nitrogen and oxygen and other elements critical to life on the Earth. So these hydrocarbon grains then settle on Titan into these vast dunes. If you see an image of Titan, you see these big swaths of dark on the surface. Those are essentially these vast dunes that are made of hydrocarbon grains. Now, the pièce de résistance to Titan, though, was revealed by multiple spacecraft and probes like Cassini and Huygans, there's likely a vast underground liquid water ocean in Titan. 40 to 170 kilometres under the surface, under the ice. An ocean may even be too meagre of a word because estimates put its size at 12 times the amount of water found in Earth's ocean. So that's just a lot of water. 12 times. Now, find that water itself. Finding water will always and forever be exciting when searching for extraterrestrial life, right? Ultimately why? Because water is the best solvent that we know of. It's all about being a solvent. It can dissolve more substances than any other known liquid. It's often called the universal solvent. It's not really. There are some types of molecules that it cannot really dissolve very well, but it's essentially the best that we've ever come across. Any life that's evolving anywhere that's based on chemistry would just basically drool at the water's ability to facilitate chemical reactions and easily shuttle nutrients and materials where they're needed. It really is amazing in that way. Such organic nutrients are all over the surface of Titan, right? I mean it's raining hydrocarbons, but the water is many kilometres below the surface. So how do these two crazy kids get together? Because if you really want to have some sort of life happening they got to get together. Now the leading theory is that this mixing of the hydrocarbons and the water is provided by billions of years of essentially impacts asteroids, comets, what have you, impacts on Titan and you can even see the craters on the surface before they're weathered away by all this activity down there. The critical question though that this research is set out to answer as they say in the study was, how much organic material can be transported to Titan's subsurface ocean through the foundering of melt in Titan's ice shell. That means that when a large impact crater is formed on Titan, it fills with melt, which is just what, just melted ice and mixed in with these organic compounds. And they can persist for millennia. They don't just like freeze over fast. They could last for quite a while. So they persist in that form. But since this is denser than the surrounding ice, it can founder, they call it, founder or sink into the planet. And the hope is that it not only reaches the water deep below, but it also can be a long-term source of organic material for millions or billions of years even. So now, okay, the bottom line of all their calculations and man, did they do some calculating, it was really interesting. They came up with an estimate of how much glycine could be supplied to this sub-ocean each year. So that's what they were going for. Now they use glycine because it's the simplest amino acid and we all know amino acids combine to make proteins which are arguably the most critical and versatile molecules of earth-based life. So if their calculations show that a lot of these organic molecules in the form of glycine can go from Titan's surface to the sub-ocean based on all this impact cratering data that they've amassed over the over the decades, then the chances of life being on Titan go way way up, right? That would be a major discovery. Enough, that would be a big enough discovery to warrant at least one heavy night of drinking, I would say. It would be really big news. The number, and everyone here probably would have already heard about it if that were the case. The number that the researchers painstakingly arrived at in the study was no more than 7,500 kilograms per year of glycine. Now that is approximately the weight of an unladen African elephant and that is not good news. And that is not good news. 7500 kilograms per year into a volume of water 12 times out of all of Earth's oceans, that's disappointingly low number. It's really like, oh man, that's like almost nothing. Astrobiologist and study lead, Catherine Niche said, unfortunately, we will now need to be a little less optimistic when searching for extraterrestrial life forms within our own solar system. The scientific community has been very excited about finding life in the icy worlds of the outer solar system and this finding suggests that it may be less likely than we previously assumed. In the study itself, the researchers say, it's unlikely that the calculated fluxes are sufficient to maintain a detectable biosphere. So that implies that even if there is some sort of detectable minimal biosphere there, it wouldn't even be detectable and we wouldn't even know even if it were there be so so tiny based on this meagre amount of glycine that could theoretically actually get down into the into the sub-ocean.

S: Yeah that's down at chlormequat level.

B: Yeah right.

E: Distinguishing.

B: The study continues saying our calculations suggest that even the most organic rich ocean world in the solar system may not be able to support a large biosphere. So very disappointing. Yeah, that was kind of a bummer when I was reading that.

S: But how definitive is it? How many assumptions went into it that could be wrong?

B: I think in terms of the amount of glycine that could get in there it might be rigorous enough to be considered definitive. I would wait until that's you know peer reviewed to really understand that. But think the takeaway for me anyway was just to put this into perspective. The limitations of the study think are pretty clear. It's very narrowly focused on predicting water and organic molecules sinking from inside craters. That's it. That's really the only thing they looked at and that of course they did that because that's the leading theory of how it gets down there. But who knows? There's lots of important caveats and assumptions that they make. And they mention many of them in their study, which was nice to see. They say, for example, in their study, bio mass generation depends on a variety of other factors that are beyond the scope of this discussion for example extremely low energetical- Energetical? Is that really a word? Extremely low energetical microbial maintenance needs or mortality could allow a population to grow to a large size despite a small biomass production rate. So there they're saying that there could be microbial-based life that just doesn't need a lot of maintenance. That it just doesn't take a lot of biomass to sustain them or maybe they live for a really long time and that could have a really big impact on the type of biomass that's down there. They also say that sources of energy other than glycine could be considered and yield higher biomass production estimates. They also talk about some of the other assumptions they made about local environments, temperature, pH, pressure, all of those estimates if they're off could have a dramatic impact on their conclusion. And they also just kind of have a throwaway mention of another study that says that the conclusion appears to be for that study that a significant contribution of organic compounds may have leached from Titan's rocky core into the ocean. So, okay, the bottom line we simply don't know much about the rocky interior of of Titan and how that could influence its ocean. We have really no idea what's going on down there underneath that surface and there's even other things like there could be some sort of unidentified plate tectonics that could facilitate mixing. It's very hard of course we don't have too many good details about what's going on below the surface. Even looking at the surface is a little difficult because there's this kind of hydrocarbon atmospheric haze on Titan that makes it difficult to see clearly what's going on down there. Plus the other side of that coin, to get the other angle to this is the other unladen elephant in the room. It's the earth life bias, right? The entire study was based on the one data point of life we have, life on Earth. And that's fine. And that's fine, because we know a lot about that kind of life. But it's also an example kind of of the streetlight effect, right? The one where the drunk is looking for his lost keys under the lamppost, because the lights the best under there. So that kind of comes into play a little bit. I'm referring to other forms of life, right, obviously, that we simply have no experience with. For example, how about life that's based on other solvents other than water? That's something it's interesting to think about. It's not necessarily happening at all on Titan, but it could be and it's interesting to think what that could be like. So there's no solvents that we know of as good as water but there are others that are almost as good. There's ammonia. It breaks down under the UV and that's the biggest disadvantage to using ammonia as a solvent but if it's sub-oceanic life, I mean UV is not getting down there, so it would not be a detriment at all.

S: How much UV do you get a tighten anyway?

B: Oh know. It's already I think it's super tiny. It's so far away that the amount of like getting there is is meagre compared to what we get.

S: Just that the surface the light intensity the sun's intensity at Jupiter is 5% that of Earth. Saturn's even less. So it's got to be very tiny.

B: And then it's also wonder, 150 kilometres right. So yeah, UV is not a factor. So it's possible that ammonia could be used as a solvent, a solvent for evolving life. But that's not even the best one. Sofuric acid is surprisingly, another promising solvent. And the best non-water solvent that's been identified appears to be carbon dioxide. So there's all these other options that are possible. The other angle to this, the other thing that kind of annoyed me was then when they were making throwaway comments saying that, if Titan's subsurface ocean is not habitable, it does not boat well for the habitability of other known icy worlds. I mean, don't go throw in shade at Enceladus or Europa because I don't think it's fair to compare them because we know that there's no real hydrocarbons littering all over those icy moons but there's other evidence that there are subsurface hydrocarbons like Enceladus has those has spewing out material, subsurface material that that has identified organic compounds. So there is reason to think that there is something going on underneath there that could potentially develop into some sort of some sort of life. So I would not take this latest news item about Titan how one specific method of mixing hydrocarbons and water doesn't look good. I wouldn't be too disappointed, especially when considering other icy moons. I'm still holding out a lot of hope for Enceladus and Europa.

S: Yeah I agree.

B: And Ganymede, I think Ganymede another good option.

S: All right thanks Bob.

Who's That Noisy? (1:11:51)[edit]

S: Jay, it's Who's That Noisy time.

J: Okay guys last week played this Noisy.

[whopping, laser-like shots/wobbling sounds]

It's a little wild, huh? All right, so let's start here. I have a listener named, first guess for this week comes from Visto Tutti and he said this week's noisy has a quality of something in a long tube. Reminds me of spinningbles down the vacuum cleaner pipe as a kid. I've done that and know that sound. I can understand why he said that. That is not correct though. Andrew Gertz wrote in and said the noisy this week sounds like someone hitting a long steel cable under tension. It sounds like a good sci-fi sound effect. Oh Andrew you have so much to learn. What you're talking about is the blaster sound from Star Wars. Look it up on YouTube and you'll see you can see Ben Burr, right? Ben Burr did the sound effects there? Really cool video of him discovering that sound. Very very interesting. Anyway Evil-Eye wrote in and said it sounds like a drum with a chord across the head being pulled over the head and wiggling back and forth like glen coach used his drum video monkey chant. That is not correct and I don't know what the hell you're talking about. You're going to have to send me a picture for that one. I didn't quite understand that one. Bill Z wrote in and said, hey Jay, love the show. I have been listening since found y'all in the pandemic, and you've saved me from a life of woo. I was listening to episode 971 with my girlfriend's 11 year old son and he said that this week's noisy sounds like a piece of sheet metal in the wind. I know you like specifics so I'm going to add that it's an 18 gauge 304 stainless steel. Keep up the good work. Well, so very cool guess. I know that sound well. I've heard it many, many times in many different fashions or whatever and it sounds close. It's not correct but keep guessing. Tell that 11 year old son he did a good job. I have another guess here, William Boysevert he said listener from the beginning and saw you at Seattle live show before the pandemic, but I've never had an answer for who's that noisy until now. So guys, remember that show? That was like, the pandemic was in the United States and about to explode and we were like in huge crowds of people. Crazy.

S: That was our brush with COVID before-

C: We were out eating dim sum like what were we thinking?

J: We were with Gary Kaseel that day. Remember Gary was there? All right so back to William he said think I've got this one is that the audio from the iPhone video slowmo. More specifically blowing out and flapping your lips in slow motion. I have clips for my whole family doing this and it's hilarious. Anyway, love you and the show. Keep up the awesome work. I've had a ton of fun with my son doing slow most stuff. It's crazy. You should definitely play around with that if you have an iPhone. All right, so we have a winner, he's close. This is a good guess and I'm going to give him the win for it because this was a very hard noisy. This is a listener named James Webb, not the one you're thinking about.

E: Oh.

J: He said, hey Jay, this makes noisy sounds like the effect used at the end of radio heads karma police which when look it up it apparently is using a delay in self-isolation and then lowering the delay rate. Not sure what the input sound is though. This sound absolutely has to do with tape, real to real audio and this guy got kind of close. I know what sound he's talking about and it does have that sound. I'm not exactly sure how Radiohead did it but let me tell you what this actually is. So again, this was sent in by a listener named Justin Fisher, and here is what the description says. Here, it says, first a recording head records the signal on the tape. Then the tape passes in front of a reading head located a little further away this head will read the signal that has been recorded creating a delay. You're using a tape machine to create an echo effect, right? So this is basically them trying to create an echo effect using a real-to-reel tape machine. So watching the video of this, the person has control over the playback head and they can move it left and right, changing the frequency of the repeating noise it's a little complicated. Listen to it again, I'll give you a way to look it up on YouTube so you can take a look. [plays Noisy] So you could look up on YouTube, origin of the delay tape echo, and you can see a video of somebody manipulating like a big reel-to-reel and changing the position of the reading head. Very cool, very interesting sound. And as analog as you get. I really thought that was cool.

New Noisy (1:16:39)[edit]

J: All right, I have a new noisy for you guys this week. This noisy was sent in by a listener named Sam Fieldman.

[Wisps, clicks, and bell-like dings]

This noisy is difficult. I'd be surprised if anyone guesses it, but it's a cool thing. I don't think I'm going to give any hints because I am surprised at how good people can guess these but good luck this week guys. If you heard anything cool or you think you know this week's Noisy email me at WTN@thskepticsguide.org.

Announcements (1:17:16)[edit]

J: Steve have really fun cool news.

S: Yeah let's hear it.

J: So in April we will be in Dallas and previously I had said that tickets for the private show were gone and they were. But I had to make a venue change and I was able to get more seats. So we currently, yes, I know. I'm very excited. So we have more seats. You could go to theSkepticsGuide.org. There are two buttons on there. One of them is for the Extravaganza, which is happening on April 6th and the second show is happening on April 7th and that is the SGU private show. This is the show where we just released more tickets there's a lot of people that emailed us. I thought the fairest thing to do instead of me emailing individual people back like I'm just throwing it out there, they're available, go get them if. First come first serve. And I wish you luck because think they're going to go really quick. This is very early but we will be appearing in Chicago. We will be having in Chicago. We will be having an SGU weekend in Chicago happening in August. Dates and everything are still being locked down but it'l be the weekend of August 17th. We will be doing a private show and we will be doing extravaganza. Now that weekend Steve you calculated this out and that weekend is our 1000th show.

S: That is correct.

J: Okay. So I will be doing something special for that show for us. It'll be a live 1000th show happening in Chicago and that's all could say right now. I got a lot of things in the works, but we'll give you more details as they come out. You cannot purchase tickets or anything for this yet because no details have been finalized, but tickets will be coming soon. So keep that on your calendar.

S: All right thank you brother.

Interview with Chris Smith (1:18:57)[edit]

- From Wikipedia: Chris Smith - "the Naked Scientist" - is a British consultant virologist and a lecturer based at Cambridge University. He is also a science radio broadcaster and writer, and presents The Naked Scientists, a programme which he founded in 2001, for BBC Radio and other networks internationally, as well as 5 live Science on BBC Radio 5 Live.