SGU Episode 497

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 497 |

|---|

| January 17th 2015 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

| Quote of the Week |

Does a man of sense run after every silly tale of hobgoblins or fairies, and canvass particularly the evidence? I never knew anyone, that examined and deliberated about nonsense who did not believe it before the end of his enquiries. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

- A bit about Cara Santa Maria

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello, and welcome to the Skeptic's Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, January 14th, 2015. And this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella,

B: Hey everybody.

S: Jay Novella,

J: Hey guys.

S: Evan Bernstein,

E: Good evening, folks!

S: And, we have a special guest rogue this week, Cara Santa Maria. Cara, welcome back to the Skeptic's Guide.

C: Thank you so much for having me.

S: So, Cara is the host of the Talk Nerdy podcast, which is excellent. But tell our listeners, remind them what else you're up to.

C: Ooh! What else am I up to? So, yeah, I do the podcast every week. New episodes come out on Monday, and then I have two regular television gigs that I do. I contribute to a show called So-Cal Connected, which is a local, public television show here in southern California on KCET, but you can also find those episodes online. And I also contribute to a show called Techno on Al Jazeera America, which is now gone international,

B: Whoa!

C: because it is simulcast via Al Jazeera English. So it in three hundred million homes!

J: Wow!

S: So you're saying that you're a terrorist.

(Laughter)

C: Yeah, you're not the first to ask me that question, for sure. And trust me, it's a little worrisome when I travel with my shoulder bag that we all got for Christmas. And it says "Al Jazeera America" on it.

(Laughter)

C: But, yeah, so those are the two things I do regularly, and then, you know, once in a blue moon, I have a new TV job, I might do a one-off show, and you can find out all about that stuff on my website, CaraSantaMaria.com.

E: I loved your work on Hacking the Planet with John Rennie, and Brian Mallo.

C: So much fun. That was a great one.

E: It was great.

C: Thank you!

J: John Rennie's comin' over to our house next month for a party.

C: Aw! I miss John. Haven't seen him in ages.

J: He's a great guy.

B: I love him to death. I can't wait to see him.

C: What's he up to now?

S: About five foot two.

B: Oh god!

(Laughter)

J: No, you did not.

S: Sorry!

B: Come on! I thought it, but I

E: Ouch!

B: would never say that!

(Laughter)

E: He's one of our dearest friends, come on!

C: Back at my house, we would call that a "Dad" joke.

J: Yeah, it is a Dad joke.

(Laughter)

C: Bit of a Dad joke.

S: So, let's get on to some of the content of the show.

Forgotten Superheroes of Science (2:21)

- Edward Lorenz, meteorologist

S: Bob is gonna continue with his new segment, the Forgotten Superheroes of Science.

B: This week, guys, I'm gonna talk about Edward Norton Lorenz.

S: Norton!

B: Norton!

(Laughter)

B: I was thinkin' of doing that. I said no. 1917 to 19-

S: Got ya covered, Bob.

B: Yes, thank you very much! He was an American mathematician, and MIT meteorologist. Have you ever heard of him?

J: Never

B: Probably not!

E: Lorenz?

B: He, yes, he was a pioneer of Chaos Theory, some would actually say he's the father of Chaos Theory. He introduced the idea of strange attractors, and he coined the term "Butterfly Effect," which I would bet most of you, most of everyone would

S: Yeah, that's what

B: have heard about.

S: everybody -

B: Yes,

S: How about the term "Sensitive dependence to initial conditions?"

B: Well, that's yeah, that's key.

(Cara laughs)

E: Rolls right off the tongue.

B: That's the key.

J: Is that your relationship, Steve? Like, what's up with that?

(Laughter)

B: Well, talking about, that kind of ties into the main epiphany he had in the sixties at MIT, when he was running a computer simulation to simulation some very basic aspects of the atmosphere and weather. And he came back, I think, from a coffee break or something, and he saw some really interesting weather patterns.

So, he said, "Ah, I want to run this again." So he started up the simulation again, and he input the values that the computers had previously calculated mid-way through, before it created that interesting bit of weather. And when he looked at the result, it was completely different, unrecognizable. Not even close to what he thought he would see.

And he thought it was a bug. But then he realized what happened was he put, the values that he entered in, were to three significant digits, which the computer had used them to six significant digits. So for example, instead of 2.031, it's what he used, but the computer had used 2.031276. He figured, you know, what difference could one part in a thousand make? Well, it turns out that it's a huge difference.

These equations, and nature itself in many ways, are recursive. The output is put back in as new input. So any time you've got a tiny error, in the beginning it might be small, but it gets amplified iteration after iteration, at each step until you have a system that's completely different than you would have.

S: And that's where the butterfly wing comes from.

B: Right, and that's where that comes in. But even more than that though, what he had found was that many of these dynamic deterministic systems like weather exhibit what's called, Steve, sensitive dependence to initial conditions. And that is the quintessence of chaos right there. Systems can be deterministic, meaning that every state is completely determined by the previous state, with no randomness thrown in, yet despite this determinism, they are still unpredictable.

I came across the beautiful definition of chaos that Lorenz had said. He said, "Chaos is when the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future." Which I think a fantastic

E: Okay

B: chaos in a nutshell right there.

J: That's cool, yeah.

B: So the idea and the subsequent development of chaos theory were so significant that some scientists will even say that the twentieth century will remembered for three scientific revolutions: Relativity, quantum mechanics, and chaos. I mean, that's

J: Not frozen yogurt?

(Laughter)

B: Not even Frogurt. So why isn't this guy a household name? That's my question. I implore everybody, read up on Edward Lorenz and his amazing contributions; mention him to your friends, perhaps when you're discussing the deterministic non-periodic flow, if you want. And

(Laughter)

B: more people should know about what he did.

E: All I know about

J: Cool

E: chaos theory, I learned from the Jeff Golblum character in Jurassic Park.

C: I think that's pretty common, yeah.

(Laughter)

E: Yeah, that's about as, as I was first introduced there, and that's about as far as I got with it.

S: Which he kind of butchered. Wasn't really

E: Oh yeah.

J: Bob, couldn't he have just summarized all of his research in like, one sentence, like shit f--ked up. Like, would that be

(Laughter)

B: Yeah, you know, Jay,

E: Very technical.

B: I think you can extrapolate all of chaos theory from that one sentence. I think you're right.

S: Although it's not as mathematically rigorous.

B: (Chuckling) Yeah, right. And before we get some really pedantic emails, yes, Pointe Carré came up with a very similar idea about chaos theory in the late 1800's. He really saw a lot of the key aspects to it, but it went nowhere. So he's worth a mention in lots of these ideas, but it was really Lorenz that really started the avalanche.

C: Why did that go nowhere? Were the mathematical models not there to back it up?

B: I think a lot of it was relativity wasn't there. That ties in nicely.

C: Ah

S: How about computer simulations?

B: Computers, yup, computers weren't there. So it just wasn't the right time. He was before his time.

S: All right, thanks Bob.

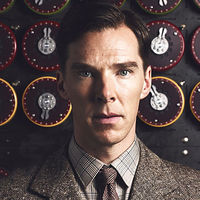

Movie Review (7:04)

- The Imitation Game

S: So we are going to do our first movie review of the year. We're going to review the

B: Ooh!

S: Imitation Game. So, spoiler alerts abound. If you haven't seen the movie, and you don't want to hear thirty spoilers right now, zip to the end of this piece.

C: So, can I ask a question, before you start this? Is somebody who actually has studied Turing's life going to really see a lot of spoilers here?

S: It's interesting that you ask. So, the movie is based upon the book by Andrew Hodges, but apparently, is very dissimilar. So the book was historically accurate,

B: Right

S: and they used that as source material. But they basically, it's not a movie of the book. And the movie isn't a documentary about Alan Turing. It's

C: Gotcha

S: It's a film,

B: But Cara

S: that's telling a story based upon his life.

B: Right

C: But I'm not gonna, like, I'm not going to have any great revel - you see, I haven't seen the film. And of course, I know things about his life that, to somebody that has never heard of Alan Turing would be like, "Oh my god! That's horrifying!" That's not gonna surprise me

S: No, no, no.

C: if you talk about this in this next segment.

S: Well, yeah, I mean, a lot of the most dramatic things about his life, I think a lot of people know. You'll know that. And those elements are all in the movie. But that, a lot of stuff is shifted around, and altered, and, you know, in order to tell the narrative of the movie, which different than reality.

E: Yes,

C: Gotcha

E: for making movie's sake.

B: Yeah, and for me, anyway Cara, the real meat of this segment is going to be the historical inaccuracies in the movie, which I find very interesting. Which don't detract

C: Yeah

B: for me the enjoyment of the movie, but I think it's fun to discuss,

S: Yeah

B: oh, this was a cool scene, but here's what really happened.

S: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

B: So that should be a lot of fun.

S: Let me just start off by saying I love the movie, as a film.

B: Oh man!

S: And Benedict Cumberbatch is awesome. I love him. I love every role he's ever done.

B: I didn't think I could love that guy any more. I really think he's gonna get nominated for some serious awards. I think he just totally kicked ass.

C: Did you guys really love him as Julian Assange?

B: Um

S: Yeah!

C: You just didn't - nobody even saw that movie.

S: I did! No, I did! He

C: He's on the Fifth Estate.

J: I didn't see it.

S: His characters are compelling! I mean, that's the

C: That's true. He was amazing in that film.

S: Yeah

C: I'll give him that.

S: Yes.

C: The film, yeah, but he was amazing in it.

J: But Cara, how about, like, the last Star Trek movie? I did not like the movie. He was awesome.

E: That's right.

S: He was awesome.

C: Yeah, that's true. I mean, he pulls out all the stops, even when the movie is kind of falling around him.

S: All right, Cara, so since you didn't see the movie,

C: Yeah

S: but you know a lot about Alan Turing. Why don't you give us a quick synopsis of the highlights of Alan Turing's career, and then we'll

C: Ooh!

S: talk about how that meshes with the movie.

C: Well, this'll be fun, because I haven't brushed up on this in a while. So you'll be my auto-correction the whole time.

S: Yeah

C: Well, you know, you were just talking about Edward Lorenz, and you were saying he's not a household name. I would venture to guess that Alan Turing is not a household name for most people, or wasn't before this movie was released, even though

B: Agree

C: he really changed the course of history. So, Alan Turing was, I guess you could say he was a computer scientist during World War II in England. A computer scientist before the concept of computer science really was a thing. And he was working in England on cryptography. So he was looking to, his biggest kind of accomplishment in life is that he broke the German Enigma code by using this crazy cool cryptography machine that he could set all these little dials. There's amazing pictures of it. And I'm sure the film actually shows it

S: Yeah

C: beautifully. And so his huge kind of claim to fame, quote-unquote, is that he broke the German Enigma code, which some people will estimate, ended the war years early, saved millions of lives in doing so. But the great tragedy of course, of Alan Turing's life was that he was openly and kind of resentfully towards the government. He was like, "I'm gay. I'm open about being gay. I'm not gonna hide the fact that I'm gay." And because of that, he was, at the time, that was a criminal offence in England. And he was sentenced to, he had to choose what his treatment or what his sentencing would be. And he ultimately chose chemical castration, which in the end, most people think, really led him to suicide, not just because of the kind of emotional detriment, but also because of a mental anguish, and chemical castration can actually lead to dementia, and all sorts of other terrible side effects.

And so, his mother still, or not still, but until her death, really thought that that was some sort of a hoax; that he didn't kill himself, that he was actually killed. But most people kind of agree, that's really what happened. And they blame that punishment for his kind of untimely death.

S: Yeah, so he died of cyanide poisoning.

C: Yes

S: But some people think that he did it in such a way that it would be ambiguous, so his mother could have denial. It was deliberate.

C: Especially

S: Yep

C: And especially only for his mother.

S: Right

C: Ambiguous just so that his mother would not think that he did that, because he knew that that would have crushed her.

S: Yeah, yeah.

B: Yeah, but there's also another belief that, you know, this was cyanide in an apple.

C: Yeah

B: Eating the apple actually killed him, which was kind of an interesting tie-in to Snow White. But some people think that because of the proximity of, whatever, the fruit of the apple to his lab, that this cyanide could have kind of like, seeped in, some how, and so it's a little bit controversial. It's not cut and dried how he died. There's a couple schools of thought on what exactly happened. So it's not as cut and

S: Yeah

B: dry as you might think. But it's ...

C: Yeah, I mean, I think that's there a lot of kind of, but some of that does kind of start feeling a bit conspiratorial, that most people, I think, and most historians agree that it was suicide. But again, but there are different schools of thought.

But the thing that I didn't even mention, which is probably the most important thing, is this concept of modern artificial intelligence, and this concept of, what we now know as the Turing test. And so, this was this thought experiment, basically, that he proposed, which is, could there be a machine that we make that is functionally indescriminate from a human. If you were playing a game with this machine, if you were communicating with this machine, would you think that a human was pulling the strings? Or would you know that it was a machine And if it passes that, it's said to be passing the Turing test. And that bar has been moved a lot,

S: Yeah

C: historically, as AI has improved. But he was really, a lot of people say, he's the father of modern computational theory. He was the father or artificial intelligence.

S: Yeah, and that's, course, the name, The Imitation Game. That's what he called it. He didn't call it the Turing test. So that's the name of the movie. So let me quickly summarize what I see as the narrative of the film, and then we can see why, perhaps, the screen writers decided to change certain things from reality.

The movie, of course, is The Imitation Game, which refers to the Turing test, but also, it's pretty clear in the film that they're trying to say that Turing himself was machine-like. And that, in the movie, there's this constant transposition of people and machines. And, in fact, when he's being interrogated by a police officer who was investigating his homosexuality, he says, "Let's play the Imitation Game. You tell me if I'm real or a machine." And then, at the end of his story, he says, "So, what do you think? Am I real or not?"

S: So, one thing that they did in the movie, they clearly portrayed Turing as on the autism spectrum.

B: Yeah, or asperger's.

J: Yeah,

S: Yeah, which is on the specturm.

E: Yeah

S: But that's probably not true.

B: (Incomprehensible)

S: Yeah, according to Hodge's book, he had a great sense of humor. He had close friendships. He did not have problems parsing social references, et cetera. He was certainly in some ways an aloof genius, but probably not on the spectrum. But I think they added that, because that's, in today's culture, that is the Sheldon Cooper, typical

B: Yes!

S: genius, right? So I think they were kind of

C: For sure

S: going with the stereotype. But I think it also enhanced the narrative of a machine-like person,

E: Right

S: who's trying to develop person-like machines, you know?

E: Yeah, it's an extra level of sort of controversy to it.

B: A cool thing about that, Steve, is the acting of Cumberbatch, I think.

S: Yeah

B: Because, you could say, "Oh, yeah, this is just like, very similar to Sherlock," but I think there were lots of differences. One, I think it was an L.A. reviewer, really, I think, hit the nail on the head. He said that Cumberbatch has this curious ability to suggest cold detachment, and acute sensitivity at the same time.

S: Right

B: And I totally agree. It was a really compelling part of that character that he portrayed.

S: Right, right, right.

C: But in some ways, isn't that a bit, I guess, disappointing, because you almost don't need that layer to have a complex character, and to have this complex individual, who is true to life. You know, this guy existed. And he changed the course of history. And couldn't, instead of some sort of, you know, as we know, genetic predisposition, some sort of mental illness, or as we said, maybe being more on the spectrum, and we know that to be kind of this, I think, I don't know, frustrating stereotype that we see

S: Yep

C: for most modern scientists, and the way that they're portrayed in the media. This is a man who had a lifestyle, and who had a fundamental kind of sense of self that was against the law,

J: Yeah

C: that was contrary to anything that was accepted in modern and kind of polite society. And that being a feature to your personality had to affect your ability to interact with people. It had to contribute to being that aloof genius. I would be aloof too if I felt like I couldn't be myself in public.

J: Well, Cara, they set that up too, because they showed some of his childhood, and again, I don't know how accurate this is, but one of his classmates who became friends with, one of the only people he became friends with, it seems from the film, ended up dying right when he was gonna tell that young boy that he loved him.

S: Yeah, so that, they fudged all of the details.

B: Yeah

S: So, like a lot of things, the broad brush strokes are true. The details they fudged for the

C: Sure

S: narrative. He did have, that friend was real, from his school. The friend did die, but it was later, I think it was a few years after they were friends. And apparently, that friend was not gay, and had already rebuffed Turing, rather than in the movie, where he was about to tell him, and then he learns that he dies. That was all for dramatic effect. And he was openly devastated about the death. He didn't hide it as he did in the movie And in fact, he had a relationship with the boy's family afterwards, for many years. So those details were all altered for -

E: Did he name his machine Christopher, as

S: No

B: no

E: portrayed in the movie? I didn't think so. I don't recall.

B: It was, what was it, BOMBE? B-O-M-B-E or something like that?

S: Yeah, B-O-M-B-E. And anyway, he didn't build the first version of it. Somebody else, I think

B: Right

S: who Dutch scientists built the first version,

B: And it worked! And it actually worked!

S: And it worked!

B: Right, until the Germans actually reconfigured it, and it stopped working. And then that's when Turing swooped in and pretty much saved the day early in the war, and made it work. But also, in the movie, they seemed to be having troubles with it for years, like a couple years. And then they have this insight, and like, "Oh yeah!" And they solve it in one fell swoop. And that didn't happen either.

S: Yeah...

B: They had successes early on.

S: Yeah

B: Then they had set backs when they reconfigured it again. And then they solved it again.

S: Yeah, they altered the time line for dramatic effect.

B: Right

S: But the key insight was the same. And that is that you could eliminate unlikely possibilities, and include the more likely possibilities, it reduces the number of possible codes that you have to test.

E: Significantly

S: Yes,

B: Right

S: so that it could, by orders of magnitude, reduce the amount of time it took for the machine to figure out what the code of the day was.

E: Yeah, they implied in the movie that there physically wasn't enough time, because the Germans would change the code every day. So you had a finite,

S: Yeah

E: you had a few, only hours each day to try to break the code, and then you'd have to start over again. And the number of permutations was just too, too many for the machine to handle. But once they were able to eliminate some of the variables, they got it down to a manageable time.

S: Yep

J: Well, according

C: Hey, what a frustrating job. Can you imagine? Like, I think that playing puzzle games, I like doing things where you're breaking codes. I like playing Sudoku. I would not want to have to do that for a living.

B: Ha ha.

S: Yeah, where lives are on the line.

C: Exactly,

E: Right, right.

C: with lives on the line, knowing

E: The world's on fire.

C: And being in such a time pressure. But this is obviously something that he loved, and he thrived on. It's a choice that he made. You know,

S: Yeah

C: a lot of the women, I'm not sure if this was portrayed in the film, but I did a mini kind of doc about Alan Turing when I went to an Association for Computational Machinery kind of, fifty year anniversary for him. And I was able to interview all these amazing people, heads of important companies, people with amazing computational awards.

And the cool thing about it is I talked to a handful of women, because of course, they're very underrepresented in that field. And they provided a lot of interesting insight about the culture of women in this field. And most of the people he was working on, when he was working towards cracking that Enigma were women.

S: Um hmm

C: It was a very heavy industry at that time, because the men were at war.

S: Yeah

C: And there were a lot of women side by side with him

J: Wow!

C: in the building. And it's pretty interesting to see how many of those women were early kind of computational pioneers too.

B: Yeah, but not only that, one of the things that kind of irked me with the movie was that it seemed like there was just this tiny group of cryptographers that were working on this, when in fact, there were thousands of people working on the project. And you really had no sense of that in the movie. It seemed like

S: Yeah

B: a bunch of guys, and the one woman working with them. And the other thing that

C: Oh, yeah, Blackly Park was massive.

B: Right?

S: Yeah

C: There was thousands of people, yeah.

J: Well, Bob, they did, they showed a bunch of

E: They allude to it.

J: Yeah, they had a bunch of people decoding - or not decoding, but transcribing all of the message-

S: Yeah, but Jay, you know, Jay, there were hundreds of cryptographers there.

B: Right, it wasn't

S: They really

B: six or seven guys.

S: did, yeah, and movies do this. They sort of reduce it down to a manageable little set. And there were characters there who never even really met in real life. They just sort of put them all together, and they changed a lot of the relationships. They were just all for dramatic effect. Those details aren't that important.

B: Right

S: One question that I read that was interesting was that the movie made the very clear point that they had to be very careful how they used the intelligence that they were getting, once they broke the Enigma, so that the Nazi's couldn't figure out that they had broke the code. So the movie said that that was their care in using, and their hard choices that they made, whereas

B: Wrong

S: a lot of historians agree that the Nazis just figured it was unbreakable, and then they were ignoring evidence that it had been broken.

C: Hm

B: Oh wow.

C: Interesting

B: But

J: So there was some level of prestige or whatever,

S: Just arrogance.

J: attached to it.

S: Just arrogance, yeah.

B: But the other thing that kind of irked me about this was that they break the code, okay? They have the breakthrough. They break the code, and then it's up to these guys, these four, five, six guys to decide? No, that's not what happened. 'Cause when they actually determined this ultra-intelligence, this was decided at much higher

S: Yeah

B: administrative levels.

S: Yeah, yeah

B: They were not the ones making

C: Oh, sure.

B: the final call.

S: Yeah, and that MI6 character probably never met Alan Turing in real life.

B: Right, yeah.

S: But yeah, that's what movies do. Again, they bring everything into one small group. And everything happens to those people.

J: I really identified with another scene that was in the movie about the unremarkable can go on to do the most remarkable things.

S: Yeah

J: And there was definitely a tone here, throughout the movie of the oddball type of person, the outlier, the person that's on the outskirts of society, and how relevant and important they are. Of course, it was obviously there, but I really liked the way they handled it. I thought it felt really reassuring, you know? I, believe it or not, I feel kind of like an outlier, sometimes. As a skeptic, I feel I'm thinking and feeling about things very differently than a lot of other people do around me. And I just thought it was really cool. I like the idea that the hero was a scientist,

S: Yeah

J: in this film, which is not that common either.

S: Yeah, at the end of the day, any movie that celebrates science, knowledge, hard work, intelligence, and the contributions of people who may be marginalized by society because they don't have traditional traits, that's a good message, you know.

C: Oh, definitely. I think any time that we can kind of draw attention to, and celebrate the other,

S: Um hmm

C: the individual who feels like maybe they're on the other side of the aisle, the individual, like you said, who feels marginalized, I think that that has deeper cultural ramifications than we think

B: Right

C: it would have.

B: Right, right

C: It affects people profoundly, especially when they're young, and they can see things that are produced by Hollywood. They can see things in the media that make them feel like they're worth being a part of society, and they have something that they can contribute to society.

S: The bottom line, this was a good movie. It was just a straight up, really good film. That's the bottom line.

C: And I've gotta say too, I think that this really contributes to this idea that I'm always trying to promote. And I'm sure you guys are so on my team, of like, we talk a lot, I'm somebody who works in the media, but I really try to have this kind of subversive sci-comm goal every time I do my work in the media. Most of what I do is science communication. But a lot of times I talk about politics, and I do some kind of entertainment stuff too, and try to sneak that science communication in there.

And it really, I think, reinforces the idea that I've long held, that the media is an active participant in changing the level of discourse in culture, and that it's a scapegoat for so many news organizations, or even entertainment kind of organizations, different production companies and networks to say, "Oh, we're just giving the people what they want.

S: Yeah

C: This is what they're asking for. We're gonna, you know, go to the lowest common denominator because that's what sells." That's what sells, because those are the only choices that people have.

S: It's self-fulfilling, yeah.

C: I definitely think so. It's self-fulfilling, and it just keeps on going. It's a negative feedback loop. And until we see more things like this, and more celebrations, more awards given at award shows for smart content, and for stimulating stories, that's just gonna keep happening.

S: Yeah, I agree. I mean, it seems like it happens every now and then, not infrequently, that a book, a movie, or whatever, that's just really high quality becomes very popular.

C: Yeah

S: And we're like, "See? People actually respond to quality."

E: Sure

S: But then, you know, at the sort of executive level, like the people making the cynical, hard decisions, seem to not learn that lesson. And I wonder how much of it is just cynicism and laziness, and they're just trying to convince themselves that the easy path is the right path, when in fact, there's no substitute for quality. Thats the bottom line.

C: Well I think that's part of it. I mean, I think in my you know, somewhat limited, but a little bit insider experience, I guess two points to be made. As a science communicator, it's really important that you never underestimate the intelligence of your audience, but you do underestimate their vocabulary.

B: Ha

C: And I think a lot of people get those things mixed up.

S: Right

C: They think because they don't speak the language, they don't understand the concepts, which is so not true. You know, we know that American society can understand really complicated concepts. They just can't speak the language of scientists. So that's an important point that almost nobody in Hollywood heeds.

But I think the second point I want to make is that, really, what a lot of this comes down to, and this sounds cynical, but I think there's a huge nugget of truth to it: Executives, the highest level

S: Yeah

C: at the studios and at the networks are so desperately afraid of losing their jobs, there's so much turn over all of the time, and it's such a power play in Hollywood to have finally made it to that level, that they stick with what won't rock the boat. They never want to push the envelope, because it has a bigger risk. That means that something could flop. And that's so scary to people, because they don't want that to happen under their watch.

S: They're risk averse. Yeah, that's

C: Totally risk averse.

S: what we hear as well.

B: Yep

S: All right, guys, let's try to get through a few news items.

News Items

Younger Dryas Extinction (27:29)

S: So guys, you know that about eleven thousand to twelve thousand years ago, the mammoths in North America went extinct. There was a huge die-off of the megafauna. And the Clovis culture also died out, because their culture was based on hunting large game. We know that this period was called the Younger Dryas. Dryas is a arctic flower that typifies that pollen, is how we know that we're at that layer, you know, in the soil.

B: Steve

S: Yeah?

B: Is it Dryas (Dry-ass) or Dryas (Dry-iss)?

S: Dryiss

(Laughter)

S: D-R-Y-A-S

J: But you said dry ass.

E: Yes, like

(Cara laughs)

E: non-wet ass.

S: Dryiss. Uh, there's the oldest Dryas, the older Dryas, and the younger Dryas from twelve thousand eight hundred to eleven thousand five hundred years ago. So, there is a raging controversy going on - I love raging controversies in science. Let me ask what you guys think: Do you think that the die-off of the megafauna in the younger Dryas, the mammoths and other big fauna, was due to a meteor strike in North America, or was it due to the glaciers melting?

E: Well, if it were a meteor strike,

B: Yes

E: wouldn't we have some pretty hard, concrete evidence of a iridium layer, or something along those lines?

S: That's a very good question.

C: It's glacial activity. But also, at least with the mammoth, isn't there some evidence of hunting activity that actually reduced their numbers dramatically?

S: Yeah, that's controversial. That was the original thought, was that the people hunted the big fauna to extinction in the Americas. But that's no longer believed to be the case.

J: Oh

S: The die-off, they died off with the Clovis culture at the same time, probably because of dramatic climatic change. It wasn't just that it become colder, it was, imagine a cold, dry, windy desert, and that's basically what North America was for a thousand years. And

B: Wow

S: yeah, just anything too big died off.

J: And that's why they called it the dry ass.

(Cara laughs)

S: Yeah

E: (Chuckles) Uh, no.

J: I'm not letting that joke go, by the way.

S: So that is the question. That's the question. So, there's one group of scientists feel that there is significant evidence for an impact. This is the impact hypothesis. And then they say, "Yeah, if you look at layers at that time period, around the world, you find spherules," which are, if you throw up rocks into the atmosphere because of an impact, as they're raining back down, the molten rock rains back down and cools, it drys in little spherules.

B: Cool

S: And also, the pressure of the impact causes tiny, little microscopic diamonds. And also, there's soot. And there's iridium, Evan.

E: Um hmm

S: So there could be an iridium layer as well. There are scientists who say, "Look! Here's the evidence! Here's the spherules! Here's the diamonds. Here's the iridium. There was an impact around this time, and that could explain the die-off in North America during the younger dryas." There are competing scientists, who like, "Yeah, that's all, you're just gathering together independent strands of circumstantial evidence. But what really happened was, there was, a fresh water stream was draining the melting glaciers into the North Atlantic, shutting down the Gulf Stream, and so it wasn't bringing warm water to North America. That's what it was."

This is yet to be resolved definitively. And every time one side or the other comes out with a study, this is one of my peeves about science media reporting, Cara, to play off what you were saying.

C: Of course.

S: Is that they treat it as if, "Well, we finally have the answer. Here's now the answer." Like, no! This is just one study in this ongoing debate where there is dozens of studies back and forth. You know, until the other side capitulates, they say, "Okay, we give up. You guys are right," and there's a consensus, you should make sure you present it as, "Well, this is still an ongoing controversy."

So, the latest salvo was a study by the non-impact scientists. What they did was they looked at the soil samples from that time period, from the younger Dryas layer, in Syria, and they found that, they've only found the carbon deposits. The droplets, what they call Salicious scoria droplets. They only found them in areas where there was habitation, where people were living. And they hypothesized that they were caused by house fires. You know, you have a wood or straw house, or whatever,

B: Oh!

S: they would occasionally burn down, and that would be hot enough to create this localized deposit.

E: Interesting

S: Yeah, so that they're just giving an alternate explanation for that soil evidence. They also give some other points, like the evidence that the impact scientists are pointing to are really spread out over a couple of thousand years, like three thousand years, so they're not all one, nice, definitive line. So, they're just not buying it. So this controversy is ongoing. I don't know why, I have this little bias for the impact theory.

C: (Laughs) You have an underdog bias.

S: Well, I don't know if that's the -

E: Special effects bias.

S: they have a little bit of the underdog.

C: Ah, there you go! (Laughs)

S: Yeah

C: I'm just envisioning a TV show where we take these scientific controversies, but we do it like a court room drama.

S: Yeah

E: Ooh, yeah!

C: Where there's lawyers arguing,

E: Present your case.

C: Yeah! (Laughs)

E: Defend your position, yes!

J: That would be cool, but

E: Classic debate!

J: Cara, what about, we morph that idea into, it's a family drama, where like, family members are arguing ferociously around,

(Cara laughs)

J: you know, like a meatball dinner.

(Laughter)

E: At a trailer park or something.

C: So basically, you're talking about Thanksgiving.

B: Yeah

J: Yeah

B: Our house.

C: Like, is that, 'cause I'm pretty sure I have people in my family who would say, "I don't think any of this happened, because I'm pretty sure the Earth was made six thousand years ago."

J: Yeah

E: Oh, you too, huh?

(Laughter)

S: Oh, really, ooh!

J: Yep

B: Yeah, we don't invite people like that.

C: Yeah! (Laughs)

J: We don't have to, Bob, 'cause they're in the family.

(Bob laughs)

(Commercial at 33:29)

Robot Poker (35:37)

S: All right, well, Cara, you're gonna tell us about one other thing now that computers can do better than people.

C: Yes! And also, in telling you about this one other thing, I want to talk a little bit about this idea of bad click-baity headlines. So, you may have seen the articles being passed around within the last few days about how poker has been solved, or poker has been hacked.

S: Hacked, yeah.

C: And robots can now play poker, and you don't ever have to play again, because all of the confusing things about poker have now been solved, which is complete and total horse shit. Like, those are very misleading headlines. So, I want to kind of take a minute, and step back, and talk about what actually did happen with these really great researchers in, I think in Quebec, who developed this computer, or this program, I should say, named Cephius. Am I pronouncing that right?

E: It's See-thee-iss

C: Oh, it's see-thee-iss. Okay, cool.

E: See-thee-iss.

C: Isn't if funny how when you read things over and over, and you never watch them? Like, especially with science journalism, it doesn't very often make it on air media. And so you're oftentimes reading it, and there are words that like, you've never said out loud.

E: I had to look up the pronunciation, Cara, so

C: Oh you did? Thank you! Thank you for that.

E: don't (laughs)

B: How is it spelled?

S: C-E-P-H

B: Okay

C: I had read a lot of neuro on my own. I was very self-taught in brain stuff, 'cause I found it interesting. But until the first time that I was in a biology class, I thought that the word was pronounced sy-naps

S: Really?

B: Ohh!

C: And I actually said

S: Sy-naps

C: Yeah, and I said sy-naps out loud in a class and was mortified when I was corrected.

(Steve laughs)

C: But that happens when all you do is read,

S: Yeah

C: you know. You don't know the vocabulary.

S: I had a friend in high school who did not have a television.

B: Yes

S: So he mispronounced every brand name,

(Cara laughs)

S: cause he never heard it said.

J: What? Give us an example, like what?

S: Haus-tees

J: For Hostess?

S: For Hostess.

C: That is hilarious!

S: That's the one I remember.

J: I like Haus-tees.

E: Hau-tees

C: (Still laughing) I love that.

J: What else? You got another one?

S: That's the one I remember. Let's move on.

C: All right, all right.

(Laughter)

C: So, that being said, cephius is a really big breakthrough, basically in artificial intelligence, wherein these scientists, and it wasn't just in Quebec. It was kind of a cool conglomeration. Oh, I'm sorry, I keep saying Quebec. In Alberta. It was a conglomeration of scientists kind of from around the world, who worked really hard to develop this program in an effort to a better understand a game, that if you're not a poker player, Limit Texas Hold'em is a very different game than no-limit Texas Hold'em.

E: Oh yes.

C: And I think a lot of people don't know the differences if they don't play poker. I played no-limit Hold'em. That's my game. I that's a very popular game right now.

S: Yeah

C: And that's what most people probably play. It's also one of the more complex games. And scientists think that they're nowhere near being able to fully understand, or being able to produce a computer program that can play no-limit Hold'em and consistently beat its opponents.

Limit Hold'em is different, because there's a finite amount of choices that you can make, and how much you can bet. You can call, bet, or fold. So, we know it, in poker, those are your only three options. When you get dealt a hand, you can either call the hand, you can raise the hand, or you can fold the hand.

In Limit Hold'em, the amount that you can raise the hand is very finite. So there's only a certain number of choices you can make. And because of that, researchers were able to come up with an incredibly sophisticated algorithm that can consistently quote-unquote "win" at poker. But I think another thing that we have to do is we have to take a step back, and we have to talk a little bit about what it means to win at poker.

I think that traditional wisdom, for somebody like myself who plays a lot of poker, and reads poker theory books, and who's really interested in the concept of poker, is that to be your best at poker, and to have a lifetime of positive earnings in poker, is to maximize your wins, and minimize your losses. That's the key to playing poker well, because poker is still, in many ways, a game of luck, in that you can't control what cards you're dealt. And no matter what, a seven-two off is very rarely going to beat pocket aces.

So, your job is to lose as little money as you can when you're dealt that seven-two off, and win as much money as you can when you're dealt those pocket aces.

E: Know when to hold'em, know when to fold 'em.

C: Exactly. And it's so much beyond that, because what Cephius does well, is Cephius minimizes its losses. And that is, in many ways, the first key to playing poker. If you hardly ever lose, you're going to end up up against your opponents. But what Cephius doesn't do, is Cephius doesn't maximize its wins. So Cephius is probably one of the best poker players out there, but it's not the best ... it's not ...

S: optimal.

C: optimal. That's a good way to put it, yes. It plays well, but it doesn't play optimally. And the truth is that if you're a person, not a machine, and you are using your own intrinsic algorithms, and having to do your own calculations as you play, it's just as necessary that you maximize your wins, as it is that you minimize your losses. Now, Cephius, because it's a machine, and because it plays heads-up poker - heads-up limit poker so well, just minimizing its losses means it's probably always going to win.

E: Yeah, it basically outlasts you.

C: It does.

E: It beats you into submission, basically, because it can just keep going, and going, and going.

C: And ultimately, with a typical poker structure, you can't keep going, and going going. You lose your money.

E: Right, that's right.

C: Like, that's the way that it works.

S: Yeah

C: So one thing that's really interesting about Cephius, and one of the sort of take aways that the researchers - and this is cool too - these Alberta researchers don't play poker. They were like, "I don't play poker. I just looked at the rules that I wrote code for this thing." And it's not that easy. They've been doing this for ten years, and they finally were able to get it to work. But none of them are expert poker players. And this paper hasn't actually come out yet. It's about to hit the presses. And so they're really excited to see how the poker community actually responds to it, because they may agree, they may disagree.

But one of the things that they have come up with, and said pretty much conclusively is that a rule of thumb that a lot of amateur poker players get wrong, is that when you're in a heads-up position, you should never just call.

S: Now, Cara, from what I read, they did not create, like, an algorithm that has some kind of fundamental understanding of how the game is played. They basically built a massive database of eleven terrabytes of data,

B: Whoa

S: that includes every possible permutation. And then they just brute-forced their way through it, just looking at every possible play, and say, "Oh, this is the statistically, the best one. Let's go for this one."

C: I would say yes and no to that. The thing is, it's a little misleading to say that they built this database of eleven terrabytes of data based on every permutation. The researchers themselves didn't know every permutation. So what they actually did, is they did build an algorithm that allowed Cephius to play itself. And in playing itself, it explored all of these different options.

S: Yeah

C: And those options were built and built and built. And then eventually, they had amassed eleven terrabytes of data, and they had amassed this huge database that looked like every possible permutation, which is something insane, like three times ten to the twenty-three

S: Yeah

C: options. And of course, if you go no-limit, it becomes three times ten to the forty-eight, something

B: Whoa!

E: That's right. Yeah

S: That's bigger.

E: Orders of magnitude.

C: (Chuckling) It's much bigger! Yes, in many, many orders of magnitude larger. So the idea here is that Cephius is a traditional example of artificial intelligence, in that it's adaptive. And by playing itself, it has gotten better at the game, because it has quote-unquote "learned" new options, and new ways to respond. And so it will always choose what they deem to be the quote-unquote "correct" play, but it won't always choose to do what we would say, maybe, is the optimal play.

S: Yeah

E: Do you know what I was thinking when I was reading this, or at least the aspect when we were talking about how the game, or the computer brute forced its way through. Do you remember the Star Trek: Next Generation episode where Data

B: YES!

E: plays the guy in Strategema,

(Cara laughs)

E: and he beats Data the first time around, where Data technically, really shouldn't have lost, but he did. And so he just plays him into a draw next time, in that, the fact that he could just physically last forever if he tried playing to a draw, and just basically because he's an artificial entity, could last longer than the other guy. He would have to

B: Yeah

E: you know, quit.

B: Good episode.

C: Yeah, that's Cephius!

E: That is

S: Yeah

E: Okay, so I was right

(Cara laughs)

E: in thinking about that.

C: That's kind of amazing. And you know, I just want to make a correction, because I'm really bad sometimes about just speaking from memory. So I did pull up the article. Limit poker has roughly three times ten to the fourteen permutations. So that's, of course, a three with fourteen zeroes after it. No limit poker has three times ten to the forty-eight permutations. So we're talking

E: Whoa!

S: It's a totally different game.

B: Forget it, yeah.

C: A totally different game. And this is something that all of these researchers are saying, "We're nowhere close to that. Don't worry, your favorite game that you love to play is not some simple thing that a computer could crack." This is actually, poker, in many ways, was the basis of game theory. And so this is a huge physics endeavor. It's a huge mathematical endeavor that continues to, I mean, these people in Alberta, I think that they're - oh, I hope I can find it. I want to say that where they were working - oh yeah, here it is.

"A decade of research from the Computer Poker Research Group in Alberta." They have a unit in their university called the Computer Poker Research Group.

S: Yeah

C: This is a huge area of study.

New Antibiotics (45:20)

S: All right, Jay, you're gonna tell about some new antibiotics on the horizon, possibly.

B: Please!

J: I am. The problem with antibiotics club is that no one is talking about antibiotics club.

(Laughter)

E: They're following the rules then.

J: Is that we should be talking antibiotics, because there's a big problem. And it's just yet another thing that we need to be worried about, and for scientists to talk about, and for people to be educated about, and then, finally for incredibly strong actions to be taken.

So anyway, this serious situation has been brewing for years, and that the fact is that bacteria have been evolving, and they've become more and more resistant to antibiotics. Historically, antibiotics have helped billions of people, and saved, you know, an immeasurable number of lives. But there's a consequence to using antibiotics. And the more we use them, the more bacteria become resistant to them. And particularly when they're over-prescribed, which we've talked about before, or when people stop taking them too soon. You know, they get the medication, feel better, and then they stop taking antibiotics, but they're only half-way through their course. And what you've basically done was breed a stronger bacteria in your system. Or hopefully, you didn't, but this does happen.

So, these semi-resistant bacteria, essentially, that would have been killed by the full course, end up surviving. And the weakest bacteria die off, so now all that's left are the tough guys. And the tough guys survive, and they go on to evolve further resistance. And as our current list of antibacterial medications become less effective, the health care costs go up every year. You know, I think the estimate was around twenty billion dollars in costs a year to deal with the less effectiveness, or the lowering of the effectiveness of antibiotics. And this cost, of course, is going to balloon as this thing becomes more and more prevalent.

Now, according to the FDA, another big contributor to this problem is the treatment of animals with antibiotics. I didn't know about this, and it blew my mind

S: Yeah

J: how much of a contributor this actually is. It's common for most animals to get treated with antibiotics to help promote growth - nothing else! Just promote growth. Right? No, I thought they treated the sic animals. Nope! They give 'em to them all. They all get it. This ends up meaning that antibiotic resistant bacteria are being passed to humans from the food that they eat!

This is why cooking at proper temperatures, guys, is very important. And different meats need different temperature, you know, always opt to have a well-done hamburger.

S: Well, yeah, you gotta cook your meats.

J: Right. So the FDA's been making moves to help this particular situation, and working with animal pharmaceutical companies help limit the use of unnecessary antibiotics. That's fantastic. Thank you, FDA for doin' your frickin' job.

S: Can I break in with a quick anecdote? So

J: Whoa! Okay, go ahead.

(Laughter)

S: I confronted, you know, I had a situation where I was faced with the offer of taking antibiotics. And I had to, "All right, and I gonna do, am I gonna listen to just my fears? Or am I gonna follow the evidence?" So, very quickly, do anybody here get grossed out at medical details?

J: Yes

B: No

C: No, I like them.

S: Okay, good. So,

E: Depends

S: I had, a few days ago, I had a little bit of back pain. I noticed I had a red spot on my back. I'm, "Okay, I gotta get that looked at."

E: Tick bite.

S: Nope

E: Okay

S: It was bigger than that. The next day, it was bigger, and really red, burning, and very painful.

B: Cool! Any pictures?

E: Tick bite.

S: That's an abscess. I couldn't get into the clinic. And then, basically, by Tuesday, it was so bad I had to go into the acute care clinic.

E: Yikes.

S: And I did. And then, so I had an abscess, a cutaneous abscess. These are almost always walled off. You know, they don't cause systemic infections. It's almost always staff or bacteria.

J: So this is on your back, Steve?

S: On my right scapula, yeah.

J: What the f--k is a scapula?

(Laughter)

(Incomprehensible cross talk)

J: I'm just askin'! Jesus. It's a little (inaudible cross talk). Okay.

E: Crawls around the ocean floor, and they fry up

S: So the treatment for an abscess is incision and drainage. They have to cut it open and squeeze out all the pus.

J: OH!!

E: And you get to save it, right?

S: Oh, no.

J: So, what happened?

S: So,

(Evan laughs)

S: I knew that that was coming. They offered me lidicane, which of course, you have to do that. But the problem with lidicane is that injecting any fluid into inflamed tissue is very, very painful.

J: Steve, isn't that odorless, and tasteless, but it can kill pretty much anything.

S: No,

(Cara laughs)

S: lidicane is an anesthetic.

J: Oh, I'm thinkin of Princess Bride. What was that stuff.

E: Oh, iocane.

S: That was iocane.

J: Okay.

(Bob laughs loud and hard)

S: This is lidocane.

B: Awesome, Jay!

E: Very close.

B: Iocane powder.

S: So, first, the doctor sprays the surface with this cold spray to help numb the skin a little bit. That was a complete waste, 'cause all that was like spraying fire on my back. And I don't think

(Laughter)

S: it helped at all.

J: Yeah?

S: Then she injects the lidocane, and that was like injecting fire into my back. And even though I knew it was coming, it was like, ten times worse than I thought it was gonna be.

E: Did you throw out an interjection of some sort.

S: Well, I always try to be stoic in situations like that, but I completely failed my saving throw.

E: You said mother f--ker, didn't you?

(Laughter)

S: It was so painful, it was all I could do.

J: So she cut into your back, your shoulder.

S: Yes. So anyway, but the good news is,

J: Your scapula

S: That, it took effect, and it really did take the pain away. And then, yeah, she cut into it, and then she spent, like, ten minutes squeezing the pus out of there. And at some point, I could tell she was impressed by how much she was getting out. At some point, she's like, "Oh my god! There's a whole 'nother pocket of pus in here!"

(Laughter)

E: Ah! She posted it on her Twitter account. That's how impressed she was.

S: Then she had to go to work for another five minutes. So anyway,

B: Wow

S: so it's all done. And then you have to pack it. And I still have the packing in my back. You have to pack it for a couple of days to absorb any remaining blood, pus, and bacteria. So that is the treatment. So, she said, "Now, I could give you antibiotics,

J: Yeah

S: but the evidence shows that if it's a mild case, if it's an abscess without any systemic symptoms, then antibiotics don't make any difference. You don't need to take them."

J: Whoa! Here we go, drum roll!

S: So,

J: What'd you do?

S: here we go. I had the decision. So, you know, I'm thinking, "God! I actually have a bacterial infection. And I'm feeling like crap." You know, I was definitely not feeling - I also haven't been sleeping 'cause I can't sleep on my back. I can't get into a comfortable position. It's like having a hot dagger stuck in your back. You know, am I gonna play it safe? Or listen to the evidence. So what do you think I did?

B: Evidence, baby!

S: How could I not? How could I not?

J: Right

E: But Steve, didn't you have the option of getting prescription filled, and then only taking it if it worsened, or something to that effect?

S: No, if it worsens, I have to go back, you know, and then get re-examined. And it will probably, and then there is an indication for antibiotics.

C: Can I interject? I'm going to lovingly tell you that I had a major eye-roll during your story because I have one that can top it so bad.

S: Okay, let's hear it.

(Cara laughs)

J: So I want to point out, before you start out your thing,

C: Sure

J: that this is a double-interjection. We are now two layers away from my news item.

C: Mine is going to bring you back to your news item.

J: Bring it home, baby.

C: And I will also keep mine very short.

J: Okay

C: When I was, in probably about 2008, maybe, no, a little later than that. Maybe 2010, I got a Mersa infection.

B: Ooh!

C: That's Methycilin Resistant Staffalococus (Inaudible due to cross talk with Bob)

B: Nasty!

C: This is a superbug. This is a bacterium that's resistant, right? It's an antibiotic-resistant bacteria. And I had what I thought was a little bit of razor burn in my under arm. And then eventually, it really started looking like a bit of a lump under my arm, and it made me quite nervous. So I went to a dermatologist. And I underwent the same thing that you underwent, Steve. They had to lance it. They had to drain it. It was in my freakin' arm pit. (Chuckles)

J: Ouch

C: So it hurt really bad!

E: Terrible! Oh!

C: It was part purple, but ultimately, what they do is they send it off to the lab. They take that, they drain it, but they take that pus, and all of that goo that they get out of it, and they culture it, to see what antibiotics will kill it. And when they realized very quickly that this was Methycilin-resistant I had to start an antibiotic regime that was really intense.

S: Um hmm

C: And it took two and a half months solid.

B: Oh my god!

J: Oh my god. Wow!

C: Yeah, two and a half

B: Scary

C: solid, on three different antibiotics.

J: Cara, would that kind of F you up? Were you having any weird symptoms because of it?

C: Well, completely. So, as a woman, and I can say this, you know, openly, because I'm not weird about medical stuff. But as a woman, I have, like, four different yeast infections during this period. I mean, it was horrible! And on top of that, I was sun sick from the bacteria. It gives you diarrhoea. It makes you very tired. The treatment is sometimes worse than the illness. And, the doctor was saying at the time that once you've had a Mersa infection, you're significantly more likely to catch a Mersa infection in the future.

S: Or you could be colonized, yeah.

J: What? Wha?

C: Yeah! And so

J: Why?

C: So, because you could carry it in your body. So then you have stuff called, oh, you have this ointment that is like, the only ointment that's supposed to work on Mersa, that you have to wipe in your nostrils, and around (I'm not even joking) your butt hole

S: Yeah

C: every day, to try

J: Wow!

C: and wipe out your Mersa colonies. This is not a fun thing for like, a twenty-three year old girl (laughs) to be dealing with.

E: Yeah

B: Oh, wow!

S: All right, that was slightly worse than my experience.

J: So think about it, guys. No, I'm really happy that, freakishly, the two of you had these stories. And I'll tell you why: Because it's very important that people walk away from this report, understanding how critically dangerous this is, and how we have to be very, very cautious. This is on the level of vaccinations. Like, we all need to have this in the front of our head. Antibiotics are important. The money and energy needs to be spent in order to fix this problem. Which means, like, look at it like this: Like, most of our antibiotics developed back in the 1940's to the 1970's is when they were developed! Right?

E: Nothing since?

J: And the last one, we haven't had any new antibiotic come up since the eighties.

S: Yeah, like '86.

J: You go back.

S: That's - to clarify - new class of antibiotic. An antibiotic works by a new mechanism. There have been antibiotics

B: Tweaked

S: that are new versions of existing

B: Yeah, tweaked.

S: classes, yeah.

J: Those antibacterials, guys, this is so cool, came from bacteria, and fungus.

S: Yeah

J: What they did, was they harvested bacteria that they found in the dirt. Literally, go into your backyard, dig up a square yard of dirt. They find bacteria in there. And then they individualize, right? So they get down to the single bacteria. They go, "Okay, this guy's different from this guy." Then they culture the hell out of 'em, breed 'em like crazy, and then they test each and every single strain, or every different bacteria, to see, like, "Well, let's test it with five hundred different things, and see what it kills." And it just so happens that bacteria fight other bacteria. So bacteria create antibacterial compounds.

S: Using that traditional method, we've only surveyed about one percent of the soil bacteria out there, because the other ninety-nine percent can't be cultured outside of the soil, outside of their native environment. So what researchers did, is they created this little chip. You can put soil samples on there, and it has like, little different pores where different individual bacteria can grow. But it can culture them with their native environment, with the native soil, so that you can culture those other ninety-nine percent of the bacteria

B: That's huge! That's huge.

S: in the soil. Yeah, so we just expanded the number of bacteria that we could mine for possible antibiotics by a hundred fold. And they've already found, like, forty candidate new antibiotics.

J: That's awesome.

S: Yeah, so there's one that they're working on right now. This is the one that they published, which has effectiveness against staffwarious and micobacteria and tuberculosis. None of the strains they tested it against developed resistance. So, now this still has to get through clinical trials, right? It may cause kidney failure. Who the hell knows, right? So these drugs won't necessarily get to market. They still have to get through a few gauntlets.

C: And also, couldn't it take years for resistance to develop?

S: Yeah, and even if they do develop resistance, we might get three or four decades out of the new drugs before that happens.

Special Segment: Suicide and Depression (57:42)

S: Well, guys we have a special segment we're gonna talk about next. For background, about a week ago, a listener of the SGU gave us a very generous donation for our legal defence fund, to support our defence against being sued. As is typical, I wrote him back, thanked him, let him know how important this was to us. And it helps us keep the legal fight going.

And then, about a few days ago, so about a week after this happened, I got an email from that listener's father. The listener was Erik Kempner. And Erik's father emailed me to tell us that the day after he gave us that donation, Erik took his own life, which was, obviously very sad. We were all very affected by that story.

What we want to do is, in reaction to this, to just talk very quickly about depression and suicide. So Erik, his father gave me some background information. He did struggle his entire life, since he was a child, with chronic depression; had been treated by different therapists on different modalities, medication, had even gotten electroconvulsive therapy at one point when he was very refractory.

He did have some prior suicide attempts. Then, as I said, about a week ago, he did ultimately take his own life, because he was struggling with his continuing struggle with depression. There also was some alcohol involved at various times in his life.

Chronic depression is a major risk factor for suicide. I think that there's a lot of stigma attached to mental illness, and to using medication to treat mental illness. You guys have probably heard that some antidepressants can convey an increased risk of suicide, but there's actually a lot of nuance to that. It's actually, getting successfully treated with antidepressants reduces your risk of suicide, because the depression is a much greater risk. It's not even clear that antidepressants increase the risk of suicide per se.

What many therapists think is that is just that when you initiate treatment, when you just start treatment, the person being treated may go through this period where they're at the very depressed end of the spectrum, and they don't really have any energy or motivation. And then, as they move sort of up the spectrum, they may get more irritable, or angry, or they may just have more energy. But they haven't had enough of an effect yet to actually get more towards a functional mood spectrum. And so there is that sort of transition phase where you may actually increase their risk of suicide. So it's really just the initiation of treatment, they need to be monitored closely, if you feel there's a risk of suicide during that period of time. But it's not really the antidepressants per se that make them have a higher risk of suicide.

It's also a myth that suicide's higher during the holiday season. Suicides, for whatever reason peak in April - we're not really sure why, in the north of the equator. Some people, again, they think it might be the return of the light, may have the same kind of effect as initiating treatment.

C: And is that kind of effect also similar in individuals who have this other mood disorder, which is bipolar disorder, that sometimes, if suicide is present in a bipolar population, that it actually happens not during the depths of a depressive episode, but actually as they're coming out of that depressive episode?

S: Yeah, it's a similar kind of thing, yeah. They're just sort of different, it's a higher risk with mood disorders specifically. The risk

C: Yeah

S: actually twenty times higher if you have a chronic depression.

C: Wow

S: Yeah

C: And I mean, for me, even, it's like, one of the biggest features of major depressive disorder. When I'm experiencing it, it is what's called Anhidonia, it's not wanting to do anything.

S: Yeah, right.

C: And so when you're in those depressive throws, often you don't even have the motivation even to do something like that.

E: I imagine there are also people who are kind of caught in the fact that they don't know what they have. They don't know to ask for help. They just don't. They have these symptoms, and they really don't know how to process it. I suppose they keep it all on the inside. They might feel that they'll be scorned, or looked at like a strange person if they were to talk about these things.

C: Well, and the sad thing is that oftentimes, we are. You know, that's the sad truth of it. And that's what, I mean, some people like myself who deals with depression, who takes medication every day. I take Selexa, twenty millgrams. That's Cetelphram. And I see a therapist once a week. And I talk a lot with other people who are dealing with this. And one of the most common messages that I get is that they can't talk about it with their family. They can't talk about it with their friends, because we still live in a culture, even progressive American intellectual culture, that looks at depression not as a mental illness, but as an illness of will.

S: Um hmm

C: It's very common that people look at depression as if it's something that you can will yourself out of. Well, if you just keep a positive attitude, you know, if you just go on more runs, you just gotta change the way that you look at the problems that you're facing. And there's a resistance in our culture to look at this the same way that we look at any other medical disorder. I need my antidepressants the same way that my mother needs her insulin.

S: Yeah, I agree.

C: And nobody scoffs at my mother because she has to take insulin, and without it, it would be detrimental. Without my antidepressants, it would be detrimental. And I look at it that same way, and I would love to see more people, especially young people who are first learning how to cope with it. I waited way to long to take antidepressants.

S: Um hmm

C: And the minute I finally was on a therapeutic dose, the same thing I said in my mind, almost everybody who comes to me and talks to me about this said was, "Why did I wait so long?"

S: Um hmm

J: Yeah, I think part of it, that problem comes from the fact that people don't realize that there is something wrong until really hits them over the head.

C: Yeah

J: It takes a long time to just become aware, "This isn't normal. I shouldn't feel this way every day. I should be," your baseline should not be horrible, ever.

S: Um hmm. So, a couple other points I wanted to make. So, if you are somebody who does have depression, does struggle with that, then obviously, you should reach out for help. There are treatments, you know, cognitive behavioral therapy, medication when necessary, et cetera. There is help out there for you. If you have somebody in your life who you feel may be at risk, talk to them. You know, some people feel like they shouldn't ask somebody if they are feeling suicidal, because you'll put the idea in her head, but that's a myth. You're not gonna do that. It's okay to ask if somebody's okay, to ask if they need help, to give them somebody to talk to. That's a good thing. You could do that.

One thing I found very interesting, so between only one in ten to one in twenty-five attempts are completed, of suicide. It's hard to get that number exactly, because for completed suicides, we have pretty good statistics on those, because those are all counted by the CDC. But not all attempts are counted. There's no real way to get at that number. But that's the range. Like, ten percent to, like, four percent are completed.

So, there are predictors of that as well, and the biggest one is access to something that you can use on an impulse. The biggest one being guns. So, people who are, to have depression, have suicidality, should not have guns around them, is the bottom line. And also, other things that you may not think about as much. Hoarding medication. So, that's, again, you just don't want to have like, a hundred pills that, if you took them all, would be a fatal dose, in the hands of somebody who may just have a bad night, you know, may have a temporary suicidality. So, those things are important as well.

So, the good news is, you can have a huge impact on suicide if you do avail yourself of treatment, if you do watch out for the warning signs. Some of the warning signs include saying that you're thinking suicidal. People that are suicidal will actually give lots of signs to people around them. You know, just don't ignore them. They'll give away cherished items, for example. So they will do things that sort of indicate that they're preparing for the end.

J: Don't be afraid to go to a therapist. I've been in therapy many times, and it's, if you find the right therapist - be selective - but when you find the right therapist, it can be a wonderful thing. And then, call a hot line, if

S: Yeah

J: anything horrible happens.

S: There is the hot line. You should know what the hot line is, if you have depression. In the United States, it's 1-800-273-8255. So, and those hot lines are effective. You know, just having somebody that's a phone call away, that you could talk to, who has some training, and knows how to talk to people who are going through this, could be very, very effective. So, avail yourself of that as well.

C: There's absolutely nothing wrong with talking about it, and with kind of moving it in the direction of a medical problem, with medical treatments, that nobody should judge you for.

S: Absolutely.

Who's That Noisy (1:07:12)

- Answer to Last Week: Sputnik

S: All right, well, sometimes it's hard to transition from these stories to other, to the rest of the show, 'cause it's a stark change in the mood, but we're gonna do that. So, Jay, you're going to do this week's instalment of Who's that Noisy.

J: That's right. So, last week, I played a noise. And, Steve, here's the sound.

(High pitched beeps that are brief, and repeated about 1.5 times per second.)

J: And that was the famous, the one and only

S: (Russian accent) Shputnik!

J: Sputnik, that's right.

E: (Same accent) Shputnik.

J: Was it that obvious?

C: Ah!

E: Wow

S: It was good! Hey, that was a good one, though.

C: Not to me.

S: It's classic.

C: Not that obvious to me, yeah.

J: So, Sputnik was the first satellite. It's an artificial Earth satellite, that was fifty-eight centimeters by

S: Yeah

J: in diameter. And it was sent up by Russia, and that was it man. That was the first, you know, outer space noise that probably made a million people on the planet, or millions of people on the planet instantly interested in outer space.

B: Wait, there's no noise in space.

(Laughter)

J: Well, that was its radio signal. And it was also scary for a lot of people,

E: Sure

J: when Sputnik was launched. It was

E: Sure!

J: really cool!

E: Cool war,

J: Very cool history.

E: brewing right along, yep. And people were thinkin', "Oh boy. Soviets have made it into space first. What does this mean for our safety? And threat of nuclear war?"

C: But you know what? A lot of really cool lamps modelled after Sputnik.

(Laughter)

J: That's right!

C: Just gonna throw that in there!

E: That's right!

C: A lot of really

B: Really?

C: cool architecture and design. Oh yeah!

E: Retro sort of, yeah.

C: Retro sixties vibe, very cool stuff that was made, modelled after Sputnik.

B: Oh, that's awesome.

(Cara laughs)

J: Okay, so this week, I have another noise. I did say last week that there was gonna be a three part theme here, which, you know, it's not, I'm startin' off easy. I want people to feel like they're included. So this week's noise is...

(Very intense whooshing sound, followed by some metallic creaking.)

S: Yep, that was a cool sound, Jay.

J: Yes. And that's this week's segment, Steve.

Science or Fiction (1:09:25)

(Science or fiction music begins)

VO: It's time for Science or Fiction.

(Music continues)

S: Each week, I come up with three science news items or facts, two real and one fictitious, and then I challenge my panel of skeptics to tell me which one is the fake. Cara, I think this is the first time you're actually playing Science or Fiction. Is that correct?

C: It is! I'm excited.

S: So, here we go! I'm gonna read three news items. Two are real, one is fake. And you have to tell me which one is the fake. Item #1: A large prospective study finds that lack of exercise is responsible for twice as many premature deaths as obesity.Item #2: For the first time scientists have been able to grow a human muscle in the lab that is capable of undergoing contraction like a normal muscle.Item #3: Immunologists have completed phase III clinical testing on a universal flu vaccine that shows as much antibody potency as existing strain-specific vaccines.

C: Who goes first?

S: Ah! It's the first person who speaks after I read the times.

(Laughter)

E: I had my mute button on.

(More laughter)

S: Well, Cara, as our guest, why don't you go first?

C: Yes, I would love to. I have no idea what the answer to this is, but I will tell you that it sounds to me like the first two seem reasonable. They all seem reasonable, but as I start to really kind of parse them, number one, exercise, if you don't exercise, it's got twice the mortality of being obese, or something along those lines.

Number two, scientists have been able to grow a human muscle in the lab. We've been able to grow organs outside the body for quite a long time. I know that tensile strength, and moving muscle parts can be difficult, but it seems reasonable.