SGU Episode 874

Template:Editing required (w/links)

| SGU Episode 874 |

|---|

| April 9th 2022 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

JK: John Kiss, |

| Quote of the Week |

I simply wish that, in a matter which so closely concerns the wellbeing of the human race, no decision shall be made without all the knowledge which a little analysis and calculation can provide. |

Daniel Bernoulli, |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Tuesday, April 5th, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening everyone!

S: How are you guys doing?

J: Good.

E: Not too bad.

J: Pretty good.

S: This is our first show recorded in April.

Declining April Fools' jokes (0:34)

S: We kind of blew by April 1st this year. I don't know if you guys noticed, like April Fool's Day it's not really a thing anymore. Have you noticed that? Is it just us?

C: Well the one thing that's not fun about it is, I want to say, so April 1st what day of the week was that?

E: Friday.

J: Monday I thought.

E: April fool's!

C: It was Friday? So I was in Mexico this past weekend. Like the second half of the week and the weekend. And they had their daylight saving and no one told us.

E: Oh no. (Cara laughs)

C: So we just like lost an hour one night and we're so confused as to why the flight times didn't line up on the way there versus on the way back. They were like, so that's kind of an April fool's joke but not.

S: I've come to the conclusion, just, as one of my life, you know, lesson things, is that yeah you know, fooling people is fun for you and never fun for the other people. And it's kind of a dick move.

C: It is a dick move.

E: Yeah.

S: Isn't it? It's just, kind of lost all desire to do it.

C: And it's either like not funny or yeah it's kind of sad. Like my friend and I drink a very similar pourover coffee, I think I might have had you guys try it once when we were traveling together. And they did, the company did like an April fool's e-mail. But they didn't, obviously mark it as an April fool's e-mail, so they were like 'you asked and we delivered - shrimp lattes are now available' and they did a whole thing about these shrimp lattes and then at the end they were like 'only today'. And my friend sent it to me and they were like this is so gross why would they do this and I was like because it's April fool's idiot. But just like did not even register.

E: On a certain level there's so many weird things that go on in the world it seems nowadays it's almost─

S: It's redundant.

E: ─right, it gets lost.

C: It gets lost, it's like an Onion article.

E: Right, I mean, you can look at something any day on the internet and think it's April fool's day. It's all blended together now.

Completion of the Human Genome (2:24)

S: So I read an article recently and Cara you independently found the same article. We've finally completed the human genome!

E: No no no. No that happened in 2003.

S: Yeah, like wait, did that happen in 2003?

B: I found the article too. It was too boring to mention. (laughter)

S: It was a little interesting.

C: It's a big deal. Just doesn't feel like it.

S: When they sequenced the genome they didn't just sequence the exome, you know, which is just the parts of the genes that get made into proteins. Although like if you get like a genetic sequence now, that's what they're doing, just the exome. They're not bothering to do all the other stuff. And if you do like the swab analysis to the companies for 300 bucks, they're just doing a snip analysis, they're not even sequencing your exome, they're just looking at little markers. But anyway, but no, I thought, I thought they did pretty much the whole genome. But there was pieces that they never got to because they were hard. Mainly the centromeres and the telomeres.

C: Yeah, those are pretty important. And I mean, I think didn't it account for something like 8% overall?

S: Yeah, yeah.

C: That's a lot.

E: So they lied to us 20 years ago.

J: Yeah what's the deal with that?

C: They round it up. (laughs)

E: I feel a little cheated.

B: If you've read the details, you'd know.

S: Yeah we get to that third or fourth paragraph, you know, where they're getting into the details, there's always that little caveat, although it was only 92% of the actual genome, whatever. They extrapolated the rest but now that they have it's helpful because we, you know, we it's good to know how. Like the centromere is like the middle of the chromosome and that's very important for lining them up and the cell division. And the telomeres across like the end caps that are, that are important for longevity, you know, they tend to shorten over our lifespan. And just knowing the structure of the DNA for for those, you know, anatomical features, you know, is helpful to understanding how they work.

B: But not dramatic.

C: But some of it is like legit coding. Like this what they're calling the satellite DNA the repetitive sequences that are really confusing and they weren't really able to figure out back then. Like I was reading like 50. like 50 genetic disorders are linked to variations in that satellite DNA over by the telomeres. Including Huntington's.

S: Yeah so it's not nothing.

C: Yeah it's not nothing. Like it it does something. And then there's these transposable ones, these like this DNA that can jump around and that wasn't all fully coded. And lots of mutations there underlie, you know, some genetic disorder. So they're, they're real biomedical consequences to this as well. Imagine you've got one of those genetic disorders and 20 years ago, like yes, we got the genome, like well, we didn't do your areas that you're focused on. Maybe in 20 years we'll get to it. 20 years.

J: Two weeks.

S: Almost 19 years ago. 19 years.

C: Yeah, that's amazing. I can't believe 2003 was 19 years ago. Stop.

More Phishing Emails (5:12)

S: I definitely have seen an uptick in phishing e-mails in the last few weeks, have you guys?

J: Few weeks oh my god.

B: For me texting Steve.

E: E-mails, text messages.

S: Yeah definitely but just, there's definitely a, I've gotten an uptick, that's all I'm saying, you know.

C: Oh, interesting.

J: What kind?

S: Well...

E: What are they selling you?

S: I'm getting bank. But I know they're fake. And, because you know it's saying stuff that I absolutely know is not true. And it's always be like 'you're about to overdraw, click now', you know. Like I know, I know I'm nowhere near that happening. And now I got one from Coinbase which is like 'somebody just tried to withdraw money from your thing' and 'click now to verify'. I'm like, you know.

C: Mine are always like 'you won a gift card'. Like yeah, I almost never get any from my bank, from like the fake bank.

E: Oh the virtual, I get the virtual currency ones regularly.

C: Wow.

S: Yeah the panic clicks, wait a minute, somebody bought something from my account, hold on now. DON'T CLICK NOTHING.

J: I don't know if you guys get the similar thing but I get a ton of emails that are all about like okay my bank, Amazon, Home Depot─

C: Home Depot! I always get the Home Depot gift card one.

J: ─Citibank and everything. But the thing is and it might be, it might be because like Gmail is is doing something to the e-mail. But it's like they spell out Home Depot home., I mean h.o., you know, like it's─

E: Yeah.

J: ─it's the title of the business with dots in between the letters.

E: Or lowercase h capital o.

C: Yeah they probably trying to get past filters.

J: Yeah I was thinking that, I was thinking that too but it's so obvious that it's fake.

C: I know, it's like they'll catch it in the next patch.

E: They only need to get, you know, a fraction of a percent of people to click on that thing to pay off. That's it.

B: It's the numbers game. I keep getting like for I've been getting, for me the uptick has been in text. Texting. And because I'm much, you know, I'm, I monitor my text much more closely than my damn e-mails because I get inundated with e-mails. But so here's a classic one I have just here: "Hey" it says "I changed my number. How are you doing, we haven't been in touch for a long time." That's it like oh yeah this is, yeah, I'm sure this is a friend who doesn't, he doesn't use my name.

C: I've never gotten one of those.

B: And part of me is like, I'd love to like explore it 'hey, how you doing', like either play a joke or just try to see what their end game is. When are they and how are they going to try to get my credit card number basically or bank information. That's got to be this, the scam but I'm just curious how they would do it. But it's just so frustrating, it's like really? How stupid do you think I am? I mean but I know there's people that fall for it and it's just like not stupid, it's just like like, my mom, if my mom saw a text like that, she would fall for that, it's just like, she's not used to it.

E: Elderly are the most common victims of this stuff.

C: I don't think I've ever gotten a scammy text before.

B: Yeah?

C: I think, I think the only ones that I get are marketing texts about like 'Do you want to sell your house?' and 'We can send you a good offer' like 'buy your mortgage'.

J: Cara is that what you think their voices are like? Do you want to sell your house?

C: Bopbropbop a mortgage (laughter) and I'm like, yeah okay. But I assume that those are just legit marketing. Somehow I ended up on a list somewhere.

E: Oh you're on many lists.

C: Yeah. But those are just marketing, I don't think they're trying to like. I mean, I've never clicked on them but I don't think they're gonna try and like steal all my info. I think they're literally like we would like to buy your house. Or we would like for you to refi your mortgage with us. And I'm like no thanks. It's so funny too, because everybody's offering these like mortgage deals right now. But have you noticed interest rates aren't as good as they were. So it makes me laugh, they're always like 'We can get you a 3.7%', I'm like that is not good compared to what I have, I don't want that. Stop trying to sell it to me.

S: All right well let's move on to some news items.

News Items

Life on Europa (8:58)

S: I'm going to start off with another discussion of life on Europa. Attempts to discover if there's life on Europa. Bob let me know if you, if you really understood this. So, we know that there's water under the ice of Europa, right? There's actually─

E: Cool.

S: ─about twice as much water as there is on the surface of the Earth, you know, under the ice on Europa. That's a massive ocean, twice as big as the oceans on Earth.

E: And a lot less plastic.

S: We assume we don't know what's on it.

E: Yeah, well I'll assume.

S: Jupiter gets about 4% of the sunlight as the Earth does, so not very much. And─

B: Quite dim.

S: ─no sunlight is going to get through that, you know, 3km at its thin spots, you know, 10 to 20km at the thick spots. So it's not getting any sunlight down there. So basically you have dark, a dark ocean underneath the ice of Europa. But there's also probably, we know it's warm, we know it's liquid and, you know, the interior of the moon is constantly being stretched and pulled by the tidal forces of Jupiter, so it's warm. And there's probably volcanoes on the sea floor, you know, of that under that under ice dark ocean under Europa. And so the question is, could there be life down there?

B: I mean all the ingredients are there, that's what I would say with that. Everything is there that should be needed.

S: Well but is there? But is there? That's the question. So what, what are they missing?

C: Yes.

S: They're missing oxygen.

B: Yeah, you're going to say oxygen but that's (Cara laughs) I don't, I'm not sure what, go ahead. (laughter) Get your argument. Well I'll just say this - there was life on Earth before there was oxygen so how did we do it?

S: With photosynthesis, that's how.

B: We had obligate anaerobes that that oxygen was poison. Oxygen will kill you, I, kill you. (Jay laughs)

S: Yes, so, because the sun is a deadly laser - not anymore, there's a blanket. You guys ever see that? History of the whole universe?

J: Yeah I saw that.

C: What is that?

S: All right.

E: I like your rendition.

S: Thank you. So on Earth, before there was oxygen, there was photosynthetic organisms that made oxygen out of sunlight, right? Carbon dioxide plus water plus sunlight equals sugar plus oxygen, right?

B: But wait, weren't there anaerobe these, these oxygenless anaerobes before photosynthesis?

S: So well you need light or oxygen, right, take your quick.

B: One or the other. All right, okay, so that's the rub, you need one or the other.

C: Yeah and when we're talking about like underneath the ocean.

S: Europa has neither.

B: Okay.

S: Bob I thought you were gonna say but what about chemosynthesis, right?

B: So Steve, so yeah I mean this this is all about chemosynthetic organisms.

S: What is the chemosynthesis reaction?

B: Yeah, I saw, I saw your blog, I read the damn equation (Evan laughs) so yeah there's oxygen in there.

S: Exactly, it's carbon dioxide plus hydrogen sulfide plus oxygen yields sugar plus sulfur plus water. So again, you need oxygen, so even with chemosynthesis─

B: Right.

S: ─you need oxygen. So there's no oxygen or sunlight in in the ocean under Europa so what's happening? All right, so, there's two possibilities, right, for life under Europe and we don't know what, you know, which if anything is going on down there. It could be sterile for all we know. But there's two possibilities if there is life. One is that it's life that figured out some other chemical reaction that doesn't require oxygen. That where it can either make oxygen or make energy without it. Now, I don't know if you guys recall this, but a couple years ago I think we talked about this where biologists looking at archaea deep in the dark ocean─

B: Love'em.

S: ─found that when the this one very common archaea, like it was 25% or so whatever 20% of the organisms that down there, was oxygen, you know, needed oxygen, you know, to survive. And they thought well it was just dormant whenever it was too low below the, it was below the level of where there's oxygen. And what they found was that no, there's still little active little buggers down there. They're actually found a way to make their own their own oxygen. They only made a little bit of it, but it was a little bit more than what they needed to then use oxygen to to to make, to make their sugars. And so they actually would also make a little bit of xtra oxygen for the environment, because even when the lights are, when there's zero light, there was still oxygen that they could detect in the water. So so something like that may be going on in Europa where some little bacteria like organism figured out a chemical pathway by which it could make energy. Either it could make oxygen or where it could make energy without oxygen. The other possibility is that somehow oxygen is getting down into that water.

B: Right, that was an interesting idea.

C: Yeah. That is the subject of a new study it's mainly a simulation and they're, they're trying to get ready for the Clipper mission, the Europa Clipper mission. Yeah, which is taking off in 2024. Will be getting to Europa sometime around 2030.

B: Eight damn years, Jesus.

E: I know, why can't it be closer?

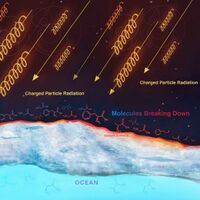

S: It's going to be in an orbit around Jupiter and but it the orbit will take it past Europa multiple times. And it's got a bunch of instruments by which you can examine the surface of your Europa. Radar to sort of peer beneath the ice and a spectrograph to see what compounds are in the ice. So anyway, they're trying to you know design the experiments they're going to be doing. And this was part of that. So, you know, they're running simulations about what could be happening on the in the ice of Europa. So what they found was that radiation, ionized radiation hitting the ice surface of Europa would would split the water in the ice into hydrogen and oxygen, right?

B: Which it does, that's a deadly, do not hang out on Europa, that's a deadly surface.

S: Yep, that's a deadly laser again. But there's no blanket to protect you. So yeah, so there's radiation ionizing the the ice and turning it into hydrogen and oxygen. So what they wanted to find out was, so there's actually a substantial amount of oxygen kind of like dissolving in these little micro bubbles in the surface ice of Europa. And their question was, is there a way that those bubbles of oxygen could get down into the ocean?

B: Down down, to Goblin town (Jay laughs)

S: And they they found that the answer is─

E: Maybe.

S: ─maybe it could. (laughter)

J: Well thanks, that's fascinating, what research you have?

S: So there's a, looking at the thinner parts, you know the chaos regions of Europa if you look at a surface of Europa these part sections of it have a really complicated surface geometry and those are the so-called chaos regions. And there the ice is thin like 2-3km as opposed to like the 15-20km at the thicker parts. So there's probably this briny, slushy warmer water getting closer to the surface there. And, in those sections, the, it's possible that you could have what they call these porous waves. So like these the bubbles are in like these porous sections of ice. And those porous sections could actually move down through the ice carrying these little bubbles of oxygen with them. Now we would take thousands of years.

B: We got time.

E: That's okay, it's been around for billions of years.

S: Which doesn't matter, right, as long as it would be like a conveyor belt of oxygen from the surface down into the ocean and delivering quite a substantial amount of oxygen into the ocean waters beneath Europa. If that's the case, then chemosynthetic organisms are off to the races, right, then then there's no problem. That dramatically would increase the prospects for life in the oceans under Europa. So that's perhaps one of the things that they'll be examining when the Europa Clipper mission gets to Europa, is the, is the plausibility of this model that they came up with, trying to model what would happen on the on the surface of Europa.

B: That's cool.

S: That's pretty cool, yeah it's pretty cool. So I didn't really appreciate how you know how dim the prospects of life were in Europa without some new chemistry or new process going on that we didn't, that we didn't know about.

B: I didn't know either, I'm very, you know, disappointed. I was much, I was, I was hopeful now I'm a little bit less hopeful because now, if this really cool thing happens then we're good but like we have, you know, when they get there they might be like oh crap this isn't happening, the oxygen is leaping off of Europa. Now Steve, what about Enceladus?

S: Yeah they didn't, there was no mention of Enceladus.

B: Same idea though, similar idea? Right?

S: I guess. I mean it would be possible.

B: Oh man.

S: But yeah, did the same factors apply?

B: Yeah, right.

S: For Enceladus.

B: But is is there the radiation? But it's the Jupiter though that's.

E: It's Jupiter, yeah, it's Jupiter emanating radiation, I'm sure it is.

S: Right because of Jupiter's magnetic field. So I don't know, I don't know, different, the condition would be on Enceladus it might be that there, it's, there's no pathway for oxygen. But I think that, you know, the possibility of like this archaea that could make its own oxygen, that's really interesting, you know?

B: Oh yeah archaea, that's the old, they're basically bacteria but they're like, they're really old bacteria, so they've got metabolisms that are so off the wall and and and ancient and they're amazing, they're totally amazing. Like, like for example radiodurans is one of my favorite. They, you blow apart, you know, blow apart their the DNA and it's like, ah, it just gets back together, you know, like I'm gonna get back together.

S: Just a flesh wound.

E: Now when people say extremophiles is are we talking the same thing or is that different.

B: That's, yeah, that's in the in the ballpark.

C: I mean they probably are extremophiles.

B: That applies to both, bacteria and archaea, I would say.

C: Well, extremophiles are just organisms that live in parts of the planet that most things wouldn't survive.

B: Right.

S: Yeah it's either─

E: A broader category.

S: ─yeah, extremes of temperature, extremes of salinity.

B: Salinity, yep that's big.

C: Or pressure.

S: Extremes of pressure, or extremes of radiation.

C: Yeah.

S: Any of those can be, qualify you as an extremophile.

C: And then like underneath that you'll have like thermophiles, so those are the ones in extreme temperature.

S: Temperature, yeah.

B: Right.

E: Yeah.

J: Steve can we use these, you know, this bacteria for anything useful?

S: The ones that are producing their own oxygen? I don't, I don't know, I mean right now it's just a research curiosity.

B: We can embed them in our lungs in case, you know, you're oxygen deprived.

E: You can breathe, yeah Aquaman.

J: I guess it depends on like what they eat and like could you, you know, could you harvest oxygen from them. Yeah but I think they give you a terrible gas, Jay.

E: Yes, oxygen's terrible.

J: No but like what if they took them to Mars and had a tank filled with them and you know just churning out oxygen?

S: I guess.

B: But I think they can you can get oxygen readily though.

S: Yeah but you have sunlight on Mars so you could make it with sunlight, if you have sunlight then oxygen is not a problem.

J: Blue skies on Mars. (Evan laughs)

S: So this, you know, I called this dark life, I don't know if anyone's else used that term. But so we may need to discover the chemistry and life cycle of dark life, like what would a completely dark ecosystem be like, you know, that's what we're talking about.

B: That also decreases the chance of life on rogue planets, right? That's, that's disappointing as hell too. God damn it.

S: Yeah, the lack of photosynthesis is significant, but again it would, it wouldn't surprise me if just that completely different life cycles evolve, you know.

B: Yeah, different metabolisms, you know.

C: Yeah, or what, maybe they could use the radiation as a as a source instead of the sunlight.

S: Yeah, yeah. It's is that a good science fiction novel there.

B: I mean oxygen is great for complicated life because there's a lot of, it's potent, right, but you don't necessarily─

S: It's high energy molecule.

B: ─you don't need it, I mean there's other types of metabolisms like based on fermentation for example. But I, but apparently, you know, you need even a little bit of oxygen, even for that, is my is my takeaway here. Which is, you know, annoying.

S: No, but I think I see your confusion there. So fermentation by definition is metabolizing carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. So that there, you can have anaerobes that eat sugar basically, that eat carbohydrates. But those carbohydrates have to be made by another organism. So once you have oxygen or photosynthesis and you're producing food essentially. Then you could have the evolution of organisms that eat the food and they can be anaerobic, that's fine. But if we, the origin of the carbohydrates, the energy storing molecules, needs to come from either photosynthesis or oxygen. As far as we know, again, unless there's some other process out there.

B: I mean I'd be fine with just pure, you know, kind of boring single-celled life on Europa or Enceladus, I'd be totally happy with that.

C: That'd be super cool.

E: Oh my gosh.

C: The problem is we'd have to, we'd have to hit it while it's alive and recognize it. Because it's unlikely that there would be fossilized evidence of that.

B: Right.

S: If it's just single cells, yeah, unless it's in mats or something.

C: Yeah unless it, yeah exactly.

S: The big issue is going to be making sure there's no contamination. Like how are we gonna yes sample the water without contaminating it.

E: Hey look, DNA, oh doh!

C: Hey look it's covered in staff.

E: Tardigrades, hmm.

B: Yeah but you find, you know, proteins that don't exist on Earth, like okay, that's no contamination.

C: Yeah like if you find stuff that has a different chirality, like there there are some real signatures that would tell you this is alien.

Ancient Skull Surgery (22:46)

S: All right tell us about ancient skull surgery.

B: Uuuh.

C: Uuuh, okay so.

E: No thanks.

J: Oh my god.

E: I'll go, I'll go for the modern version, thank you. Do you know that I actually, so I'm going to talk a little bit about trepanation, you guys know about trepanning, right?

B: Yeah it hurts man, it hurts.

C: Cutting holes in skulls. I actually have, this is, this is the weirdness that is Cara Santa Maria, a very dear friend once for Christmas got me a trepanation drill bit.

B: Cool.

C: I know.

B: A little blood on it?

J: Like, from what decade?

C: It's not ancient ancient, it's probably from like a hundred years ago?

J: Yeah.

C: So it was like used in medicine but like the type of medicine you would not want to undergo.

E: "Medicine".

C: We know that trepanation is an old practice and actually, I didn't even realize this but there's evidence in Morocco of trepanation from 13 000 years ago.

B: Whaaat?

C: Yeah and that seems to be the oldest potential evidence. But there's a lot of evidence from like a thousand years ago. We've also seen ancient Egypt, so other kind of northern African areas around 4 000 years ago. But in north America there's sort of been a dearth of evidence, and most of it has only been within the past millennium. Yet, a researcher, a bio-archaeologist named Diana Simpson who works at the University of Nevada Las Vegas recently presented her investigation at the American Association of Biological Anthropologists annual meeting which was about a week ago as of this recording, called Surgery before sedentism: Probable trepanation during the early prehistoric period in southeastern North America. So this was a region of present day Alabama.

E: Go Bama! (Cara laughs)

C: Where actually sadly these remains were basically grave dug in the 1940s. It's a a site called the Little Bear Creek site, a burial mound that's covered in seashells. The man, the kind of specimen in question as well as 162 others were excavated at that time. And kind of sent to different museums and things like that. And so these specimens have been studied by paleoanthropologists for a while. And this researcher was looking at an interesting wound on the head of this specific man. Kind of in the frontal bone and realized that it had markings, markings that were very likely caused by some sort of tool. So they they look like scrapings. The researcher believes that these scrapings are indicative of the of tool use and not created naturally by the injury itself or by an animal or anything like that. And then of course the hallmark of trepanation which we've probably read about before is what?

S: Healing.

C: Yeah, healing. So there's evidence that the bone continued to heal for possibly up to a year after the, after the skull surgery. And the interesting thing about this specific man was that he was very likely an important person within the culture. So his burial was pretty atypical, there was as she words it "an extensive mortuary assemblage" it seems of the era that he was most likely a shaman or potentially a shaman who does tattoos, because they found some really cool turkey bones that at other anthropological sites were thought to be basically like crude tattoo guns. So they looked similar to other sites where they've recovered these turkey bones, sometimes deer bones that are pointed on one end. And there was, not at this site but at other sites, again, there was evidence of pigment at the tips of them and then sometimes shells that were full of pigment as well. So they were almost like pots for whatever was being used as the ink. So these very very kind of early crude tattoos. But the interesting thing about this specific example here in north America is that it's by far the oldest and it's the only example that we have of hunter-gatherer individuals utilizing trepanation. Every other example we have is from sedentary groups, groups that had already settled in certain regions and weren't moving. But this group was a hunter-gatherer group that was known to be kind of nomadic in nature. And that's, that's an interesting idea that trepanation would have somehow either been spontaneously utilized or that that knowledge and wisdom would have been passed to these individuals. Because this is the earliest case that we know now here in north America.

S: Yeah and it's possible that it was not just a ritual, that was actually medical procedure.

C: Yeah it's, it's actually probably likely that it was medical, because this individual also had broken bones and a wound above their eye socket I think. And so they think either, you know, he was attacked or he fell down. He had some sort of traumatic injury and very likely was, had maybe brain swelling or maybe there was a piece of skull that was invading his brain that needed to be removed. So they saw this as a means to potentially save this man's life. As opposed to many of the examples yes that we know about trepanation which are kind of like letting out evil spirits, very like psychic, psychiatric surgery, things of that nature.

S: Right.

C: But I love this stuff. I love like old brain surgery stuff, it's fascinating that people actually lived.

S: Yeah they would survive for years after.

C: For years sometimes yeah, I cannot imagine that that initial period after the surgery, or during the surgery I should say. But definitely during and immediately after was a particularly pleasurable time for these individuals.

E: How did they survive the infection?

C: Yeah, exactly.

E: I don't get it.

S: The infection would be the killer.

C: Yeah, that's the killer. I mean, that's and and even with examples of this, it is usually the killer. Like even when we think back to Phineas Gage the very like famous example of a frontal lobe injury, from the railroad tamping went kind of through his cheek and out his front frontal lobe. He ultimately, he, he lived, he lived for quite a long time. But I do think he ultimately succumbed to infection years later.

J: I didn't know that.

C: Yeah he lived for long enough for people to see his personality change and, you know, draw a lot of really interesting conclusions about what the frontal lobe does but, yeah, I think he did ultimately succumb, even years later.

S: He had seizures as well he had bad scenes.

C: Right, yeah yeah. He did. And so yeah there's, you know, infection is pernicious. And it can lay dormant, it can come back again and again and especially when you got a hole in your head, you know, unless, now what we would do is, we would, we would put a plate or we would, you know, have some sort of means to close that up but back in the day. I don't know how they covered it, they might have put like a leaf on their head or something.

S: It's not, it's not as big a deal as you think though. I mean having a piece of your skull removed, and as long as the skin is closed over.

C: Yeah.

S: If you would, it would [inaudible] over.

C: But they wouldn't have had sutures so the hope is...

S: It's not that big a deal actually.

C: Yeah I mean the hope is that there was a skin flap to heal, you know what I mean? That they weren't suturing it. And then that you sort of, are careful. (laughs)

S: Yeah.

C: Right, you just gotta be careful around that area. But I think for this dude it was like on his forehead, so it was pretty exposed.

Artemis Stuck (30:11)

S: All right Jay, I understand that the Artemis I mission is stuck.

J: I mean that's a little dramatic, I mean of course NASA was going to run into some snags as they, you know, they they slowly brought that monstrosity out onto the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center. So this was, this happens on on Monday, April 4th, NASA began fueling the Artemis I rocket and they had to stop due to a yet another technical issue. So this is the second time they had to pause testing. The first time NASA tried to fuel the Artemis I rocket was on Sunday, April 3rd and they stopped before pumping propellant again because there was an issue with pressurization fans on the mobile launcher. So to be more clear about that, those fans keep hazardous gases out of areas where technicians work in those areas that are enclosed. So it was a safety issue and I guess they resolved that issue on Sunday. So on Monday the 4th they tried again to pump about 700 000 gallons or 2.6 million liters of super cold cryogenic fuel to the rocket. The technical issue this time was a stuck vent valve found on─

S: Yeah, it was stuck.

J: ─it was stuck, yes, it was. But they could unstick it. This was found on the the mobile launcher and this valve is about 160 feet or 49 meters up in the air. And the valve is used to vent pressure from the rocket's core stage as they add fuel. So if you, if you picture the fuel tank that's inside of the, the core rocket. That fuel tank is huge, right? And they have to fill it with the propellant which is oxy, it could be hydrogen it could be oxygen, just depends on, you know, what that particular rocket needs. So they're filling it up and there's a valve at the top of the tank that is used to regulate the overall pressure inside of the tank. And it's very very specific and very tricky. That pressure has to be maintained at a very specific pressure and if that, if it goes out of bounds, then bad things can happen. So they they figured out that that valve wasn't working and they, they immediately started to drain the fuel out of the tanks. And they said the rocket was about half full when NASA had to remove─

B: Or half empty. (Evan laughs)

J: ─yes depends, does it depend on which way you're going? I don't know. (laughter) In this case I, you know, what's unbelievable guys, on very trusted websites I'm reading oxygen and I'm reading hydrogen and I don't know.

S: It's both. It's got to be both Jay because they burn one with the other.

J: I totally agree but Steve, it wasn't clear, that's all I'm trying to point out is even on like space.com and websites where you think they'd give you a very nice clear picture, it wasn't that clear.

S: Well probably because it is both, I mean actually it's gotta have both in there if it's liquid. I mean if that's the fuel, I mean the fuel could be oxygen and something else, you know, but if it's hydrogen-oxygen, which is the best, because it's got the best specific impulse. Then yeah, you have liquid oxygen, you have the hydrogen, they burn them together and it's the fuel and propellant. Because that's also what gets shot at the bottom of the rocket.

B: Right.

E: Right.

J: So as we record this right now on Tuesday the fifth, we don't know if NASA is going to try one more time today. It's very likely, I think, that they'll try tomorrow, which will be Wednesday. And by the time you're hearing this it could be, you know, days or almost a week later. But, you know the takeaway here is that we have an amazingly complicated system that they built. So many things could go wrong and the fact is they haven't run into that many snags at all. This is exactly the type of things that they're trying to find ahead of time before they schedule the the full launch. This is really cool. So what they're doing during these tests, is they will start the real countdown clock 38 hours. Like that's about how long the the countdown clock has to run for to go through all of the the pre-checks and steps and everything, right? When they test launch the SLS on the launch pad, they run through the countdown all the way down to T-90 seconds, right? From 38 hours. Then they'll do this several times until they're satisfied with all the various systems and that they all check out. Then they'll say okay, we got that part of it down then then we'll take the countdown now to let's let's go to the 10 minute mark and run through like the the last 10 minutes and go through those systems over and over and over and over again. All the way up until just before engine ignition. And there is a transfer of control from, from the command center to the actual Orion module. At some point, in the very last few seconds I guess they they transfer control over to that to that system and they're testing that out as well. So knowing that, that's one of the very last things to take place. They need to make sure that all these systems are working exactly the way that they need to in order for this launch to be safe. And another thing that is significant but completely out of the hands of humans is there's other factors like whether there's lightning within a certain number of miles, I think it's five miles. There can only be, it has to be less than a 20% chance of lightning within a five mile radius of the launch pad. The winds have to be less than 37.5 knots. And the temperature must be above 41°. And there's a lot of things like this going on. Like a lot of things that factor in that must-haves in order for them to launch. And you know when they're checking in, you know, when you hear in it when they're at the command center and they're talking and are like blah blah blah check in and guy is like yep blah blah blah check in. Oh yeah we're all set.

E: All the stations, yeah.

J: Yeah, they're, they're checking in with all of like the sub systems the people that are in charge of all the sub systems that can see like a heads up display of what's going on. Is there a portion of this puzzle functioning.

E: Yeah it's like a set of eyes specifically on each component of the entire mechanism going on. There's tons of tons of things to check.

J: But you could imagine that there's people that are beyond them like that are even in a, you know, a more subdivided subsystem that's telling them it's okay. So it goes up the chain, right, you know they got a lot of people eyes on, it's not just the people that are in the command center that are giving thumbs up. It's like lots of people on the ground and all over the place.

E: Yeah imagine the thumbs up are coming from that team's leader and there's a team of people below each of those people, makes sense.

J: So, overall, you know, even though there was, you know, you wouldn't even call them setbacks. They just had issues that came up during these tests as predicted. Everything seems to be in fantastic shape, they're still saying that they they are thumbs up for a June launch. Which, and it's going to be late June, it's going to be late, I know, but it's coming guys, they're gonna light that sucker up and we're gonna see Artemis I take off. It's gonna be glorious man, it's gonna be one of those things like you just don't get to see it that often.

E: That would be worth the trip going there and seeing that, definitely.

J: I totally would do Artemis too in a heartbeat.

E: You wanna go?

J: I would do it.

E: I think we can go.

C: Where is it launching from?

J: Well this one, Artemis I is gonna launch from Kennedy Space Center.

C: Okay.

E: Oh my gosh.

B: But you need to get, I mean I saw the last shuttle launch, and it was awesome, don't get me wrong, it was great, but you're so far away.

J: But it's more about, Bob, you were there, it's more about the camaraderie and the vibe that's in the air, you know, there's just, it's just an exciting, you know, place to be and to watch the rocket. You're basically as close as you can get. Unless you have inside passes and things like that.

B: VIP baby.

C: When I was, but Bob, when I, when I saw the Soyuz launch in Kazakhstan, from Baikonur, we were relatively close. And it was like, it kind of hurts, like you don't want to be close. Like it's a little painful.

S: You have to be like five miles from the Apollo when it took off. Like miles away.

C: And I feel like we were only, like I could be wrong but I feel like we were only like a mile from the launch pad or something.

S: If you were close you would literally die. It would kill you.

C: That sucks. (laughs)

E: So, so does that mean they find a lot of dead birds in a five mile radius?

S: Yes. Absolutely, absolutely.

E: So animals die as a result of all this?

S: Yeah.

E: Because the animals don't know it's coming.

S: It burst your lungs, yeah just the pressure wave is so intense that it will kill you.

J: They put signs up for the birds though to stay away. (laughter)

S: I think, this is like because I was, when I visited there, I did watch like a smaller rocket launch, I'm having a vague memory, we have to look it up, I think they do like try to chase them away right before the launch somehow.

E: Scare them with sounds.

C: Yeah they might do the the...

J: They're called shoers. There's a bunch of people that just run around yelling 'shooo' out. (Cara laughs)

E: They all have umbrellas and they open and close them real fast and run around.

J: But let it sink in guys. You know this is, this is history being made. This is the largest rocket, the heaviest lift rocket ever to launch. This thing is going to be louder than anything else that's ever happened out there. It is ushering in, you know, I don't want to minimize anything that SpaceX has done and believe me, you know, SpaceX has accomplished quite a bit. And it has helped the industry a lot. But this is the heavy lift rocket that we've been hearing about for a very long time. And it's happening in about a month and a half, we're gonna see some some magical thing happening.

E: Oh my gosh.

J: I really, I highly recommend that you take them, that moment out of wherever you are that day and watch it, you know? Why not? You want to, you want to be able to tell people hey I saw that rocket lift off. And Artemis too, I mean when when people are being sent back to the Moon and then this is the beginning of a permanent Moon base. That is. That's the big one. As far as I'm concerned.

B: Yeah.

S: So Kennedy has several bird deterrent methods that they use.

E: You looked it up? Yes yes, go go.

S: Like firing off large cannons. And they also have people shooting blanks at individual birds. Because it's not just that they don't want the birds to die, they don't want the birds to be in the way, you know, they don't want a bird hitting you know part of the rocket or the space shuttle, whatever, as it's, as it's launching. So yeah they were, they were very fastidious about clearing the area of birds.

J: That makes so much sense, I mean, you know, a piece of foam.

S: Yeah, right?

E: Yeah just hit, yeah it fell off and did them in.

J: Foam. Now of course, you know, when the rocket comes off the launch pad, it's not moving that fast. But still, you don't want a bird or an animal to get in the way or get into a mechanism or whatever. Like it's got to be, they've got to be very fastidious.

C: Oh yeah aren't birds, and I mean I know this is different because I'm talking about general aviation. But isn't bird strike like a reason for a lot of bad things happening with airplanes.

E: Yeah, airports, oh yeah, they have bird deterrent systems, definitely.

C: Yeah, like it can take down a whole plane if a bird like goes through the engine or something.

[commercial brake]

Most Distant Star (41:48)

S: All right Bob tell us about the most distant star ever.

B: Yes so NASA tantalized us recently with the announcement on March 28th of a major announcement to come two days later. (laughter)

E: Wait a minute. They can't do that, that's not fair.

B: As Steve said we learned that Hubble had discovered a record-breaking star that was the most distant star ever discovered.

E: Hubble's still paying dividends, that is amazing.

B: Oh yeah, I know, but I don't know about you guys, but whenever NASA makes an announcement about a big damn announcement, it just sets me up for disappointment, right? In my mind I go right toward─

E: Dark matter.

B: ─evidence of alien life, a stable wormhole or maybe an alien ship in orbit or on Jupiter or something. So then when they come back with the news a few days later the discovery, it's like whatever it is, doesn't matter. It's a huge letdown and I'm just like pissed off in my head. And, just stop it NASA and make one announcement, please.

S: You watch too many movies Bob.

B: Okay, I'm done.

E: Right?

S: But they could be announcing that we're about to get wiped out by an asteroid, so that's something.

B: Yeah that I would look forward to.

E: That would meet your expectations, right Bob?

B: So but, despite all that. This, this is cool though. NASA said the following, this is the quote:

"NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has established an extraordinary new benchmark: detecting the light of a star that existed within the first billion years after the universe’s birth in the big bang – the farthest individual star ever seen to date."

So that's really cool, that's worth celebrating, you know, maybe you don't need to make an announcement about an announcement about it but, you know, it's still, it's still (Evan laughs) really good.

C: So now wait, the farthest star also means the oldest star or no?

E: Yep.

C: Okay, that's what I thought.

B: Well no.

E: Wait, what do you mean no? [inaudible] lied to me years ago?

B: No, I'll say that. There, there could be stars that were created after this, that were smaller and therefore much longer lived than this one, which was a big one.

C: But this one is the farthest and the oldest?

B: The the farthest, this is the farthest one individual star that we've ever, that we've ever seen.

C: But we've seen older stars?

B: There are older ones, that have lived longer than this.

S: You guys are talking about two different things. Cara's talking about that this star as we are seeing it was the farthest back in time and that is correct. Bob's talking about long-lived stars.

C: Right, yeah, that's not what I'm asking you about, I'm asking you as we're seeing this star, it is the farthest away physically.

B: Yes.

C: Which also means it is the oldest that we've ever observed.

S: Back in time.

B: The oldest light, the oldest light, I'll say that. (laughter) Okay, so this was accomplished by scientists working on Hubble's Reionization Lensing Cluster Survey program called RELICS which is a really cool acronym, so okay, so here are the stats, here are the stats. The stars named Earendel which is just wonderful, since it's not a stupid number designation.

E: Is that from Lord of the Rings?

B: It's beautiful, it's a beautiful name and it sounds like elves live on it, right?

J: It does.

B: Right out of Tolkien. The name means "rising light" or "morning star". So it formed about 900 million years after the Big Bang when the universe was just seven percent of its current age. A long time ago. The photons that we see now took 12.9 billion light years to reach us, which is so funny because from the photons point of view at the speed of light they think whoa we were just created, and now we're absorbed by hell, what the hell? Evan laughs) So yeah for them, not such a long time, for us crazy long time, silly photons. Okay, so here's another cool interesting perspective. When this light left the star, it was four billion light years away from the baby proto Milky Way at that time, whatever the hell shape we were in. Four billion light years away. But due to the expansion of space though it took 13 billion years to get here. And its origin point is now 28 billion light years away. So universal expansion, I mean that's just, it's so cool, it's traveling all this time and but the universe is expanding very very fast as well, so it really messes with the numbers. So there's not a lot, there's not a hell of a lot we know about the star yet. Wwe do know that it's millions of times brighter than the Sun and at least 50 to 500 solar masses. So it's a lot of star going on there, that's a lot that's big big big. But if you want specifics about its mass or temperature or even the type of star we're gonna have to wait. And of course it's almost certainly pretty much dead now. Because this was a good, because it's a good sized star, it has a lot of fuel but that doesn't translate into a long life. Because it reaches such amazingly high temperatures that they last on the order of hundreds of millions of years. Whereas our Sun for example is billions. And even lower mass stars are even much more than that, so it's, so it's definitely a dead husk somewhere. So the story though, the one, the part of the story that I think is most intriguing though is the detection itself. And this is, it's fascinating. First off, total chance. This is a total like throwing a die with a million sides to it. Like boy, this is a nice coincidence. They were very lucky. So this is what happened, they were studying a relatively nearby galaxy cluster. And then notice that the cluster was acting as a gravitational lens, right? You get enough mass together, you're going to get a gravity so intense that it's actually bending light and acting like a lens. So you got this gravitational lens going on. And it's magnifying and distorting the light from a far more distant galaxy, galaxy behind it, behind the cluster. Oh look, here's another galaxy really, really far away and the gravitational lens smeared that light up from the galaxy into a long crescent shape. And they call that crescent shape a sunrise arc which is kind of pretty.

S: So Bob it was a galaxy far far away?

B: Yes.

E: And long time ago?

B: And yes. I see what you did there Steve. (laughter)

E: Bob's puppet voice. Okay, so all right, so you got this smeared image of a galaxy that's really far away. That's not a big deal, oh, you know, here's a smeared image of an early galaxy. Even this galaxy, the distance that this galaxy was, that's not a big deal, that's happened before. They found these smeared out very, very distant very, very old galaxies before. They've done that. Not a big deal. But was this, what was especially fortuitous here, was that a single star was greatly magnified. Kind of pulled out of this smear. This galaxy smear, oh look here's one little star, that's in that galaxy, that just happens to be super, super clear and just pops right out. And that of course was Earendel. I wanted to go into more detail though. Like why? Why did this star pop out? Because this is just a smear of light, these galaxies, they never see the stars. They just see a smear of light, which is like all of the stars. So why did this one tiny, or why did this star pop out of that smear? So I found this quote from NASA that explained it and never heard this before, so: "he star Earendel appears directly on, or extremely close to, a ripple in the fabric of space. This ripple," yeah, that's kind of like yeah, I'm not sure exactly, like, it's on a ripple, like wait a second.

E: Is ripple a technical term?

B: So let me finish the quote, they say: "This ripple, which is known in optics as a “caustic,” provides maximum magnification and brightening." So okay I kind of get the idea but this still, like what exactly are you talking about. So then they offered a really good analogy. And what they do is, they compare it to the rippling waves on a pool. Right, we've all seen, we've all looked at a pool that's rippling a little bit and we and you look and these ripples cause these dancing light patterns on the bottom of the pool, right? We've all seen, it's really, it's completely random and chaotic. But there you see these patterns of bright and dark spots. And that, that's exactly what this is. You've got these ripples in space. That this star is just positioned just so perfectly that somehow it's magnified. Like like those light, like the light is on the rippling, on the rippling pool. And it was magnified many many thousands of times. Even more than the galaxy itself. It was extra extra magnified because of this fortuitous placement of the star. And, bam, that's how Earendel popped out from the galaxy. Which is really cool and it's very, it's, it's rare, I'm not sure, you know, how much that's happened in the past. But it's also very interesting that this, this high resolution image of the star is good, could last for years. It, you know, it's not something, that's so fleeting that it only lasts a week or a month. This could last for multiple years, which is good, because then we could study it even more.

C: Wait Bob.

B: Yeah?

C: I gotta get back to the ripples.

B: Yeah.

C: Are these like, so these ripples in space, are they gravitational? What's causing space to ripple?

B: Well I mean, it's got to be related to the gravitational lensing effect. So let me, let me look at the quote again.

C: Okay.

B: It appears directly, it appears that the star Earendel appears directly on or extremely close to a ripple in the fabric of space.

C: If space is rippling like condensing or expanding, like physically, you know, rippling, it must be gravitational, right?

B: Right.

S: [inaudible] it's really muscular. (laughter)

C: Ripped.

B: That's actually a quote from a Bruce Lee movie Return of the Dragon, very nice Steve, very nice, very nice, I like that. So yeah, so it's definitely related to the gravitational lensing effect. And I guess it was an especially potent section of the lensing effect that gave it an extra magnification. That's what it's got to be, I can't think of anything else. So really cool. So here's a quote from Brian Welch who was a lead author and astronomer. He said: "Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we do know. It's like we've been reading a really interesting book but we started with the second chapter and now we'll have a chance to see how it all got started." So that's cool because, yeah, because these, because this star is a very early, very early star and it's very different from the stars that are around now. So, all right, so what about the future? Following up observations of Earendel, James Webb, James Webb is basically going to take over for the Hubble and it's going to analyze the stars infrared light. And Webb has obviously much better optics than Hubble, especially, you know, in its, in its specific wavelengths. And it should be able to confirm, you know, that this yes, this is a star and it's a single star. Because it could potentially possibly be a binary. Which they think is not impossible at all. It could very well, could be a binary or a single star. So James Webb can just could distinguish that. And it'll be able to measure the stars chemical composition. Which would be very revealing because like I said, the universe back then it wasn't filled with many, wasn't very filled with many metals back then, so stars did not have, yeah much metal in them, which greatly changes, you know, the you know what the star itself. It's very important and that's why we classify stars in like in population one, population two etc. So that can be revealed as well by James Webb. And James Webb I think may even break this this final record by Hubble, probably the last biggest, you know, a record-breaking discovery that Hubble makes. But James Webb could potentially go even farther. But, I'm thinking, well really? I mean, this sounds like a very very rare situation where you've got this the smeared galaxy in a gravitational lens, where one star just happens to be placed so perfectly I don't know, that sounds pretty uncommon to me. Maybe this, this won't be repeated for a really long time or maybe James Webb will just find one in the first few weeks, I don't know. But uh keep an eye out for this, this is really interesting and yeah interesting story to research. Very, very cool.

S: Yeah that's cool and Evan, your Lord of the Rings instincts are very good. So this is Earendel, e-a-r-e-n-d-e-l, which is old English for "morning star". Earendil with an il at the end, otherwise the same spelling is is the half elven mariner who voyage to Valinor, who was also the father of Elrond and also Elros the king of Numenor so.

C: Oh my god.

E: Wait, are you are you reacting to what Steve is saying or the fact that Steve is saying it?

S: Yes.

C: It's like, yes (laughter) wow. It goes so deep.

E: 12.9 billion deep.

Fake News (54:15)

- I'm a fact-checker at Snopes, the internet's authority on viral hoaxes. Here's how I tell if news is fake.[5]

S: Evan, tell us about fake news.

E: Fake news, we've all heard of fake news. Well Madison Dapcevich, she wrote a piece published at Business Insider about how she as a Snopes fact checker is able to detect fake news. And of course she suggests and it's something we've been saying forever on this podcast, that many things in life are kind of complicated and they fall on the spectrum, they're not all black and white, they're not binary. This is the fogginess of truth detection, you know, but some nefarious people in some cases under informed people, will use those gray areas or incomplete sets of knowledge and data to take advantage of other groups of people and consumers of news or to push agendas, promote their biases and sometimes outright deceive. So she writes, you know: "Rarely do we see a post that is purely "true" or "false," and more often than not, we come across claims or rumors that lack important nuance.". Yes where have we heard that before, we've talked about that before. Human nature wants to, wants answers and explanations but: "Bad actors take advantage of that to spread falsehoods online, inciting emotions and further polarizing groups of opposing ideologies.", absolutely. And she brought up the Russia-Ukraine conflict sort of as the example in this particular article about how this is prevalent especially with, well I mean right now it's what, it's the most prevalent or one of the most prevalent events taking place right now in the world. Here are a couple of the examples of things she has had to investigate about claims about the Russia-Ukraine conflict. All right, claim: a video shows Ukrainian soldiers killing civilians in Chechnya, so in March 2022 a video was circulated on social media in an apparent attempt to justify Russia's invasion of Ukraine. And it supposedly showed Ukrainian soldiers ruthlessly killing civilians in Chechnya. Okay, so, she did the digging into it and guess what? That's wrong.

S: It was fake?

E: It was a scene from a movie─

S: Oh I love that. [sarcasm]

E All right and furthermore the movie soldiers in the film are playing Russians not Ukrainians. And the Russians are killing the Chechnyans at the start of the second Chechnyan war. So that's just one example. Here's another, here's another example. Video shows Ukrainian tank crash through Russian barrier in 2022. No, miscaption, video dates back to 2014. So basically you have these old old things that are being recirculated and repurposed and just being thrown out there as news, coming out of the, of the current conflict. But in fact with a little investigation you find out they're absolutely, absolutely bunked. Did you hear about this one? Ukrainian army cats trained to spot sniper lasers.

B: Oh no way.

E: You know cats and lasers that whole thing? How they, you know, go after the laser? So here's the claim: in February 2022 a photograph started circulating on social media that supposedly showed a Ukrainian army cat named Mikhail who had been dubbed the "Panther of Kharkiv" after it was trained to detect the lasers of an enemy snipers. And while they're not certain of the photo's exact origins it's been online actually since at least 2018 and it was posted by a twitter account called you ukr me cats and dogs. So yeah, you know, these are just, just a couple a couple of the examples that they, that they cite. So and she gives some you know good tips for people to, when they read about these things, especially with current events, how can you detect, you know, what you're reading is real and what you're reading is probably not real. She talks about being able to well identify coordinated inauthentic behavior. And that refers to the use of multiple social media accounts and pages to hide the real identities of those in charge to mislead or influence people. For example, you know, if in Facebook you've got this section of a page called page transparency and it allows the viewer to see the information about who is managing the page. What country it's originating from, and all the changes that have been made. So with, found within that page transparency section there's data, like the page creation date. You can, you can also tell if it was something, you know, very recent or something that's been around a long time. You can tell if it's sort of sprouted up as just a sudden means to get people to try to believe whatever, whatever story or whatever this particular page is putting out there or if it has been established around for a while and so forth. You can look at the history of where of what this has been and where it has been. Another thing she brought up is something I had not heard of before, Cara I think you have heard of this before though.

C: What?

E: Copy pasta?

C: Copy pasta?

E: Have you heard that term before?

B: Yeah.

S: Oh yeah.

J: Oh yeah, I have.

C: What is it?

E: Why did I not know this term before reading this particular article.

B: Evan, I just heard it for the first time a couple, like a week ago.

E: Right. It's a portmanteau for copy and paste. Copy pasta is the 21st century equivalent of─

C: That's not a portmanteau of copy and paste!

B: No it's not.

C: That would be copyaste.

E: Well, okay.

S: It's sort of a portmanteau, it's yeah, it's poetically tweaked because copy pasta is funny.

C: It is funny, but it's not a portmanteau.

E: Do you guys, you guys remember chainmail?

C: Of course.

E: Remember when you used to, did you ever guys get ever those in the actual mail back in like the 1970s, when people would mail letters and saying, chain letters, okay now you have to pass this letter around to ten more, ten more people.

C: They wasted stamps on that?

E: They did Cara, that was a real thing.

C: Stamps were pretty cheap back then, right?

E: But you know it takes on a whole new meaning in the age of the internet as opposed to using the the postal system to to spread this stuff. Plus also, it gets a little tweaked, you know, it's like playing telephone, you know, you get little tweaks also along the way. So that thing has no and often no recollection to what the original idea was. If you go ten generations down down the line it may have totally, entirely changed, if it was even legit to begin with. So you have to be able to spot that kind of stuff. Yeah, be on the lookout for troll bait obviously, we talk about trolling quite a bit. I think we all you know know what that is. But you know, Steve, you know─

C: Don't get sea lions.

E: ─all right and Steve you know there are people on the, you know, commenters who intentionally start arguments or, you know, to us you know stoke the fires and that's, that's kind of all they do yeah you have to, you have to be careful of those, you know. And it's not just comments it's posts, it's pictures, graphs total, you know, distortions. Always as a means sort of to drive a particular traffic maybe in some way but also to kind of get people very upset. You know, so these are kind of the basic tools. And of course it's all stuff we've talked about, stuff we come across regularly and try to inform our listenership about as well but I'm glad someone who's actually on the inside at Snopes is also writing articles and further informing people about what to what to be on the lookout for.

S: Constantly. We just talked about that at the front of the show, it's only getting worse so this is part of media savvy which is now part of skepticism you have to be able to identify, or at least have a process, you know, by which you evaluate these things. And at least don't knee-jerk accept, you know, as real, anything that you see like that. That's going, coming to you through social media and sometimes even mainstream media. Like they get things wrong too.

C: Of course.

S: So you just have that skeptical filter for everything, absolutely.

Who's That Noisy? (1:02:09)

S: All right Jay is Who's That Noisy time.

J: All right guys, last week I played this Noisy:

[creepy, eerie, ringing tones]

Kind of has like a Logan's Run vibe.

S: Yeah it does.

E: Or Outer Limits.

J: Right, you get the idea. So what do you guys think this is?

C: Yeah like at first it was wind chimes but then it became digital.

J: Yeah, I agree.

S: I lost track, was this a sonification or no?

J: It is.

S: It is, okay.

J: I should say that. And just so you know. This is a sonification. I told you I would tell you when I do that. I don't play these that often because I think they're very hard to guess.

S: Data turned into sound.

J: Correct.

J: So a listener named Adam Hepburn and his entire family guessed he said: "Jayseph, I saw the discord notification pop up on my phone", you know, he knew it came out early so he had his daughters with him. So his daughter Silvia said: "It's a creepy ladybug" his daughter Elise said: "A creepy bug" and he said: "I should have asked her first because she always says what her sister says" and then I think his wife is named Kristen and she said: "I just assume everything is a rain stick" (laughter)

C: I constantly hear rainsticks too. It's either rain stick or a talking marine mammal.

E: Oh gosh.

J: So that his guess was, because he knew this was a sonification, he said: "A sonification of an fMRI signal of someone who died while hooked up".

C: Oh god.

J: I thought that was really provocative. So you guys are not correct although you win the family award which I've never given before.

S: And just made up on the spot but go ahead.

J: I did, I just made that up.

Another listener named William Simpson wrote in said: "Betcha that that's the SARS-CoV-2.". Now I thought that was a cool guess as well. Because it fits in. I did say that we talk about this type of thing, like there was like a theme, thematically here.

C: I also love how he said it "betcha that's the SARS-CoV-2" like yeah, he looked it up on the google. (laughter)

J: We had another, another listener, that's not correct, it's not SARS-CoV-2. Another listener named Marcel Janssensnsns Cara laughs) said: "Hi Jay, no idea but since you stressed it was creepy and that fitted it could well be some bug signal. So I say it's the solidified sound of the electric muscle signal of beetles or some other bug flying and starting to fly."

C: Oh bugs aren't creepy.

J: Some are. Definitely. Okay, that is not correct but I think that's a fantastic guess.

Another listener named Jim Kelly wrote in said: "Hi Jay, guessing that this week's Noisy is a sonification of the hairs on the body of a spider. Perhaps a tarantula."

S: Getting closer.

J: Getting, definitely getting closer this some fantastic guess and there is something in there that is about the answer so we did have a winner from last week and that winner is Josh Weber. And Josh says: "Hey everyone, I think this week's Noisy is essentially the sounds of playing the strands of a spiderweb. I read an article this week that talked about sonification of spiderwebs. Based on the clue given this seems to fit perfectly with creepy." Yeah so this is the sonification of a spiderweb where, you know, the some type of visual scan is done and they mathematically like measure the length of the spider webs and they're able to transpose those spider webs into sounds and that's what you're hearing. And I thought that Bob you would particularly like this one.

C: I don't think they're transposing them, I think they're transducing them?

J: Well there's lots of different ways to sonify something.

C: Okay.

J: So as an example like a very common sonification you'll hear is they'll take a picture of space and every time a star or a galaxy, you know, comes into view from a left to right scan of the picture, they'll play a note. But the bottom line is, that this is a, this is what a spider web would sound like if it played music, I guess. If it was turned into sound. I think it's fascinating, you know, you think about the complexity of spider webs. One listener wrote it and said and I think it was Visto Tutti who said that this was definitely not a drunk spider because if a spider is drunk it'll make a crooked web.

C: Oh right yeah, that's funny.

B: Yeah I've seen the webs of the spiders on acid and the webs they made.

C: Those are cool.

J: Yeah, they are distorted for certain.

New Noisy (1:06:27)

J: All right I have a new Noisy for you guys this week. This noisy was sent in by a listener named Josh Nankeville and here is the noisy:

[somewhat creepy beeps, chimes, and vibrating strings with intermittent whirs and synthesized chords]

J: Yeah, I don't know why I'm playing these creepy ones.

C: I know, is that not just like a continuation of the last week's?

E: Spiderweb part two?

J: This one is not a sonification of any kind. I will give you no more hints.

B: The cobweb sound, music. (laughter)

J: It's the sound of the actual spider getting drunk. No this is a, this is not a sonification. And it's very cool, I think you're gonna like it and I don't think anybody needs any hints. Just go out there and tell me if you know what it is. And also this week, if you've heard anything cool, please send it to me, you never know, I might just use it on the show. You can e-mail me that sound at WTN@skepticsguide.org.

Announcements (1:07:36)

J: Steve we have a few things going on yet again.

S: We do, we have a new extravaganza is coming up in Arizona.

J: We have two extravaganzas in Arizona as a matter of fact. But let me give you them in order of when they happen. So at 12 o'clock noon on April 23rd in Bethlehem, PA we will be doing another SGU private show. This is when we record the show in front of a live audience. We absolutely promise that we do and say things during that live show that never make it to air, you will be the only person to hear it. And a lot of times there there is something crazy or profound or really funny going on. We really like to have fun during those shows.

S: So seriously, seriously we've started adding segments, we're like this is only for the live audience, this will never be in the podcast. And it's specifically designed to be like out of bounds for the, for the podcast.

C: Also sometimes George makes us cry.

S: Yeah.

J: Yeah, it happens. Mostly he makes us laugh though. So yeah George, and George will be with us for that show. Then we have something called the No-Show. Now we did the No-Show I believe in 2019, you know back in before times. This is a different show every time we do it. Usually there is music involved in, of some kind, and then we do some type of performance. So this this time George is going to be playing "Seven Songs with George Hrab", he'll have a backing band. I guarantee you that that's going to be fantastic because the band that he has is amazing and George is amazing himself. And then that night on April 23rd for the no show we will be doing a live version of our game show called Boomer vs Zoomer. This game show is a, it's a contest quiz show between the generations. We have four people, each from a different generation. And they are playing a head-to-head quiz game. And as an audience member, guess what, you get to play along, you actually get to play for real. You will be asked questions and you will be answering those questions and they will have an impact on the game. So I would love it if you joined us.

Then we go to, now the extravaganzas. We're going to be having an extravaganza in Phoenix, Arizona on July 15th and we will be having an extravaganza in Tucson, Arizona on July 16th. All of these things can be found on our events page that's theskepticsguide.org/events. And on top of that we will be adding in two private shows for the Phoenix shows. So every time we do an extravaganza we will be doing a private show at some point. Either the day before or the day of. Those details will be coming soon, but you can see most of this information on our events page. Please join us, we just had a great time in New York and Boston and we want to bring it to you.

C: And Jay, maybe we could tell the nice folks out there, what the difference between an extravaganza and a private show is.

J: Sure Cara, no problem. The private show is a podcast recording of this exact podcast. The only difference is you're in the live audience and we're doing some things that you were the only people that will hear it. It's, it, it's more interactive in a sense. We definitely, you know, talk to the audience and everything. You get a chance to chat with us before or after the show. And in general we're just you know having a lot of fun and it's the podcast. But the extravaganza, you know, it's a stage show, this is a completely different animal.

S: Yeah it's like a variety, game stage show, totally different.

J: Yeah the theme of the show is "You can't trust your senses", you can't trust what your brain perceives and we show you tons of examples of how your you can't trust what you see here and smell, everything.

S: And we humiliate each other. Basically. (laughter)

J: We do. More accurately, George puts us into different, you know, live comedic bits where we have to do something. I'll give you an example of my favorite one is called "Freeze Frame" where the audience will yell out suggestions for a movie. George will pick the movie. And then, you know, four of us have to freeze in position to to try to get the fifth rogue, who doesn't know what the movie is, to guess what the movie is. And oh my god, I mean some insane situations have come out of that that bit and we love doing it. So we do a bunch of different games like that and it's a great show, it's about an hour and 45 minutes. And, you know, please join us if you haven't seen it, you know, we're getting incredible feedback. We'd really like you to come check it out for yourself.

S: And people have asked us what are these VIP tickets I see for sale on there. So for if you, for the VIP you get a swag bag and you get to hang out with us for an hour usually before the show, it depends on how we have to schedule it. You get pictures with us, you know, so that's like, which is typical, you know, for now, for like live shows for there to be like an intense, you know, behind the stage meet and greet kind of extra stuff. So that's, that's what that is.

C: And also preferred seating at the show.

S: You get preferred eating at the show. Yeah, absolutely.

C: Yeah so for people who are wondering you know if we do two cities that are near to one another, we design it in such a way that you could attend both an extravaganza and a private show, they're both completely different in your city. You could of course come to the next city too, but they're designed so that you don't have to.

J: No extravaganza is the same thing because we never run the same exact thing twice. It's, every show is completely different.

Questions/Emails/Corrections/Follow-ups (1:12:54)

Email #1: Evolution & Racism

S: All right let's do a very quick email, this one comes from Jacob from Tracy, California. And Jacob writes:

"Hi! I saw this article and thought it was interesting. https://www.umass.edu/news/article/disbelief-human-evolution-linked-greater-prejudice-and-racism Normally you hear from religious fundamentalists that accepting evolution leads to genocide and all of that nonsense, but it’s nice to have confirmation that that is not the case, and in fact accepting evolution is related to less bigotry. Makes me wonder then, how much less bigotry there could be if everyone accepted evolution? Here is the related abstract https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35175082/ Thanks for everything you do! Jacob Tracy, California"