SGU Episode 849

| This episode was transcribed by the Google Web Speech API Demonstration (or another automatic method) and therefore will require careful proof-reading. |

| This transcript is not finished. Please help us finish it! Add a Transcribing template to the top of this transcript before you start so that we don't duplicate your efforts. |

Template:Editing required (w/links) You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 849 |

|---|

| October 16th 2021 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

| Quote of the Week |

-- We’re human beings with the blood of a million savage years on our hands, but we can stop it! We can admit that we’re killers, but we’re not going to kill today. That’s all it takes...knowing that we’re not going to kill today. (from Star Trek Episode 23, A Taste of Armageddon) |

first quote: Captain Kirk |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. (applause) Today is October 13th, 2021, and this is your host, Steven Novella. (applause) Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: Evan is away with his lovely wife enjoying their 20 year anniversary weekend extravaganza situation. So, yeah, he won't be joining us this week, but we hope he has a good time. Yeah, occasionally, you know, people have lives they got to get to. We're not seeing a whole day recording podcasts. Lots of anniversaries happening.

S: Lives are overrated.

J: Yeah.

J: So, I haven't been on the show in two weeks.

J: Yeah, that's right.

C: Although I have to admit, our recordings were tight.

C: Oh, I know.

J: When one person is missing, it's like we should always do it with less than one person, you

S: know? It also takes some time off my editing time, just one fewer track.

S: Oh, right.

S: It takes a ton, but significant, it's noticeable.

S: But it's good to have five people on the show.

S: So if one's personally missing, we're still good, you know?

B: Yeah, that's true.

B: It's like a gaping hole.

S: Yeah.

COVID-19 Update (1:07)

S: So how many, what percentage of people who get COVID would you say get long COVID, like chronic symptoms?

C: 20%.

C: And you're meaning anybody who's had a positive test, not anybody who's gone to the hospital

S: or anybody, but just... It just says diagnosed with COVID.

J: Okay.

B: My guess is 20%.

B: No, I'd say 5%.

C: 21%, Price is Right rules.

C: More than half.

C: Yes, I win.

C: More than half.

C: Wow, that's f'ed up.

J: That is so depressing.

J: Yeah.

J: Holy shit.

C: And when you say long COVID, though, you're running the gamut.

C: Yes, they have symptoms six months later, basically.

C: But like anything from anosmia to like severe neurological dysfunction.

S: Yeah, yeah.

S: It doesn't mean they're all devastated.

S: It just means they're not back to baseline.

S: Right.

S: Wow.

S: More than half get quote unquote long COVID.

S: I mean, I think when the dust settles on this pandemic and we look back and the researchers have an opportunity to dig into the data, we're already seeing it.

S: But I think this picture is going to emerge of how devastating this pandemic was.

S: And it goes way beyond just the mortality numbers.

J: So much happened.

J: Steve, is there anything that they can do to treat long COVID?

S: We don't really know.

S: We're just kind of treating the symptoms now and trying to figure out what is causing it and why some people get it and some people don't.

S: I think we mentioned on the show a few weeks ago or maybe a couple of months ago that there is some evidence that some people with long COVID had their Epstein-Barr virus activated by the COVID infection.

S: So it basically kicked off this secondary infection with a virus that was in their body but not very active.

S: And that's what's giving them the fatigue and a lot of the long COVID symptoms.

S: But again, that's probably not, that's certainly not everybody with long COVID.

S: There's just one potential mechanism.

S: There's a lot of post-infectious syndromes.

S: Could be your immune system remains activated or it could have just done some tissue damage to your organs and then they have to recover.

S: There's lots of things that can happen.

S: You know, if you're, especially if you were sick enough to be in the hospital, you're not going to necessarily just bounce right back.

S: Viruses could really lay people low for a long time, even when the infection itself

C: is not there. There's also, I just recently on Talk Nerdy, I don't even think we've aired it yet, interviewed a neurologist who was talking about like conversion disorder, functional neurological disorders, these sort of psychogenic types of disease states and how we've long looked at health as very binary.

C: Like there's the biological genetic side over here or the like infection, you know, pathogen side.

C: And then over here, there's the sort of like psychological and emotional side.

C: And that really a much more global understanding of health.

C: And I think a much more modern view is this biopsychosocial model that all these things feed in.

C: And you see heavy psychological components to long COVID, heavy psychological.

C: Like we're talking, people who are laid out, sometimes who were intubated, who dealt with PTSD from being in the ICU, people who lost relatives and loved ones to COVID at the same time that they were sick.

C: I mean, all of these things feed into each other and you cannot tease them apart.

S: So just for context, so you say modern, I learned the biopsychosocial model of medicine in medical school in the late 80s.

S: So I mean, it's not that new.

C: But still, the sensibility isn't there.

C: You very often see, oh, that's psychogenic.

C: Let's refer to him to the psychiatrist instead of, no, there's still a mechanism at play here just because these seizures don't look on EEG like epileptiform seizure doesn't mean that a non-epileptiform seizure isn't medical.

C: It's not purely psychological.

C: There's something going on in their brain.

S: And also, my perspective is as an academic neurologist.

S: So I'll just tell you that that thinking is totally baked into neurological practice, at least as I'm experiencing it.

S: We actually had a non-epileptic seizure clinic in our neurology department.

S: We were just talking about this at Grand Rounds, the fact that when we make a diagnosis of a non-epileptic seizure, in other words, it's psychogenic, it's psychological.

S: That doesn't mean we just ship them off to the psychiatrist.

S: It's like this is still a neurological issue that we need to be part of and to address.

S: And I spent a lot of time talking to my patients about the fact that these things are what we call comorbid and they feed into each other and we can't always disentangle them cleanly.

S: The psychological, the neurological, the stress effects, the metabolic effects, whatever, these things all sort of are interacting with each other and we have to address them all.

C: Yeah, they're really disentanglable.

C: I understand that there's some situations in which it's helpful to try and say, what component of this is hereditary?

C: What component of this had this precipitating event?

C: But ultimately, trying to tease all of those things out, I do think you lose a gestalt of the disease when you do that.

S: Yeah.

S: So I think we try to tease them out on the population research level and then on an individual patient level, we just see them all as one coherent thing that we have to address.

S: Is it your sleep?

S: Yeah, it's your sleep and it's your stress and it's your migraines and it's this other thing that's happening and you're not exercising.

S: But it's like all these things together and let's see what we could do to turn the ship around and to address all these issues.

S: But yeah, you can't say, it's a migraine, here's a pill, that's not going to work.

S: We know that.

C: Mapping that back to COVID, it's like we are living through a global and collective trauma.

C: And we often try to...

C: Yeah, it's true.

C: I think it's become so normalized for a lot of us that that part of the equation goes unsaid.

C: But a big part of what I've been doing in therapy with patients who are dealing with these kinds of issues, whether they had COVID or not, which a lot of them have had COVID, is like that part of the equation is an undeniable part of the equation.

C: And so somebody who's dealing with long COVID and has like neurological, respiratory, other somatic symptoms, there's no way they got through this without any psychological symptoms as well.

S: Yeah.

S: And the biggest challenge, it's very difficult talking to patients about it because most people have a Dr. House kind of thinking about disease, this very binary, you need to make the diagnosis and then give me the treatment for the diagnosis and then I'll be better.

S: They think very concretely about their illness because that's what they were told on television, that's to think about it.

S: And sometimes most of what I need to do is break people out of that very narrow clinical narrative of what's my diagnosis?

S: Sometimes that's like not even a meaningful question.

S: It's like there's a complex interaction of factors going on here.

S: We could throw labels around, but really we need to address this complex set of situations here, not just treat this one thing.

S: And sometimes there is a diagnosis lurking in there.

S: Sometimes patients do have migraines, but that's rarely the beginning and ending of their story.

C: And it's also, it's all threshold component.

C: We talked about the threshold dependent.

C: We talked about this last week, like even COVID, like if the reagent test or the diagnostic test that we're using doesn't detect a high enough viral load, it's going to come back negative.

C: If it's a high enough viral load, it's positive.

C: But really that's still an arbitrary line in the sand.

C: So do you have COVID, do you not?

C: Well, how heavy is your viral load?

C: Can you pass COVID or can't you?

C: Well, how heavy is the viral load?

C: How much protection does the other person have based on mask usage, based on vaccination status, all those different things.

C: And I think with long COVID, it's going to be ultra complicated because these, lots of these things are secondary, tertiary, quaternary effects of a viral infection.

S: We may talk about this later in the show as well.

S: This idea that not everything is black and white, yes or no.

B: Cara, I have a question.

B: What comes after quaternary?

C: I don't know.

C: What is it?

C: Quintier, tetra?

C: No, that's tetrad, it's still four.

C: Quintenary?

C: Quintenary.

C: Quaternary, septiary, octenary?

C: Yeah.

Shatner in Space (9:30)

S: I wanted to say before we go on to the news items that we should mention William Shatner today became the oldest person in space.

S: How awesome is that?

S: That's awesome.

S: Went up in the Blue Origin ship, this is the second one with passengers and made it into space, suborbital, not in orbit.

S: The whole ride was 10 minutes.

S: The name of the rocket was the New Shepard rocket named after Alan Shepard, one of the original Mercury 7.

J: They should have named it the Enterprise.

J: I mean, come on.

J: Yeah, well, whatever.

J: Don't even get me going with that.

J: It's not whatever, it's a big deal.

J: I think it was a brilliant marketing decision.

J: I'm an original series fan, of course.

J: Captain Kirk is an important person in my life.

J: I just think it was really cool that they did that because I'm hoping that it interests people in science.

J: I hope some people out there, young people who, oh yeah, like Star Trek or whatever, they have a connection to getting into the science of what's going on.

J: We have multiple companies now that can put people in outer space.

J: This is a big deal.

J: The fact that William Shatner got to take the ride and got to be one of the first people and everything, that was a really big deal to me.

S: Yeah, it was nice.

S: That's going to be a hard record to break, 90, the oldest person to go to space.

J: I don't know how long that will stand.

J: Yeah, it's cool to know that a 90-year-old body can go into outer space and take a hard landing and he took it.

S: Yeah, it's cool.

News Items

Mass Extinction 30 Million Years Ago (10:59)

S: All right, Cara, tell us about this mass extinction 30 million years ago.

C: Yeah, so there are some headlines going around based on an article that was recently published in Communications Biology.

C: The article is called Widespread Loss of Mammalian Lineage and Dietary Diversity in the Early Oligocene of Afro-Arabia.

C: That describes what the article is about.

C: The headlines, not so much.

C: You might see some that say, a grim, huge extinction event happened 30 million years ago and we just only noticed, or the press release out of Duke, the climate-driven mass extinction no one had seen.

C: Well, we were pretty aware of this mass extinction.

C: The difference here is that we know that it also happened in an area where we didn't think it happened.

C: That's going to be the crux of this argument.

C: The extinction event, which is well established, is the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event.

C: It happened at the end of the Eocene, about 33.9 million years ago, into the beginning of the Oligocene.

C: And we saw a large-scale extinction of both flora and fauna.

C: It is somewhat small compared to the other mass extinctions that we have looked at.

C: Historically, we thought that most of the affected organisms were marine or aquatic.

C: We also saw that there was a lot of turnover in Europe and in Asia.

C: Notably, one of the things that went extinct during this, or one of the entire, I don't even know, is it an order?

C: It might even be larger than an order, that went extinct during this event are the ancient cetaceans, also known as the Archaeoceti.

C: And it's a group that really spawned, I guess you could say, evolutionarily, both the toothed whales and the baleen whales.

C: But this group itself went extinct during, of course, the toothed whales and baleen whales went on, but that group itself went extinct during this event.

C: So I don't know, a little trivia for your pocket.

C: There's a lot of question about exactly what was going on at this boundary.

C: We know it was a major climatic change based on, you know, looking at glacial evidence, ice core evidence, sea level evidence, you know, a lot of isotopes from the seafloor.

C: It doesn't seem like there was any one clear, you know, there wasn't one volcanic event or even potentially one asteroid.

C: It could have been several large meteorite impacts.

C: It could have been multiple volcanic events.

C: Also we saw a decrease in carbon dioxide, a change in oxygen isotopes, and a big change in the Antarctic ice sheets.

C: But I think most of us are pretty aware now, even if we don't study this stuff, because it is very complicated, that climate change is complex.

C: And a lot of things happen when, you know, some things happen.

C: Are these like runaway effects?

C: That's not really the takeaway from this study.

C: The takeaway from this study has to do with specifically, as was mentioned in the title, the African and Arabian continent.

C: So this was a time, I think, right prior to the Arabian Peninsula breaking off.

C: And historically, researchers thought that these areas of the globe were sort of like left alone during this Eocene-Oligocene transition.

C: So like I mentioned, we saw massive change, and we've known for quite some time that there was massive change in Europe and Asia.

C: We also saw massive change in like Antarctica, in different glacial movements.

C: But Africa and Arabia was largely thought to be sort of untouched.

C: What ended up happening here is that researchers from across the globe, in combination with Duke, they looked at a large trove of fossils, mostly from the sort of Egypt area, over a long period of collection, like decades and decades and decades of collection.

C: And they specifically focused on a few groups. They focused on, oh gosh, this is going to be fun. It's pronunciation time. You guys ready?

C: Yes.

C: Anomalurid and Hystricognath rodents. They focused on Carnivorous hyenodonts. So these would be extinct predatory mammals with hyena-like teeth. The Anomalodurae were these rodents that are also known as scaly-tailed squirrels. And then also I mentioned, and this one is probably narcissistically the most interesting to many of us, the Anthropoid and Stepserine primates. So these are the primate ancestors of apes and monkeys. So ultimately our ancestors. And they looked at these different groups and what they found, based on a lot of very complicated phylogenetic research, and specifically focusing on dentition, so looking at the topographic changes in teeth, they found that there was a massive bottleneck that occurred in this region of the planet. That the diversity that existed prior to the end of the Eocene and entering into the Oligocene all but disappeared. And especially with regards to the primates, only one tooth type seems to have remained. And that tooth type eventually led to all of us. And the really interesting takeaway that a lot of the researchers say is like, we may not have survived this.

C: We may not be here if this extinction event had wiped out our primate ancestors.

C: But ultimately, even though it dropped the diversity down to almost nil, some organisms survived.

C: Those organisms had a very particular type of tooth that ultimately led to a new diversity, right?

C: Because we see this happen a lot with evolutionary genetics, that there's all this diversity, there's an extinction event or a pinch point, a massive bottleneck.

C: The diversity goes down to almost nothing.

C: And then with time, we re-diversify.

C: And ultimately, all of the diversity that we see on the planet today with regards to monkeys and apes does seem to have come down to this one pinch point based on this one very specific type of tooth, which is pretty freaking interesting, if you ask me.

S: And Cara, they made the point that the tooth anatomy is a good marker for diversity, because it also reflects the diversity of what you're eating.

S: Yeah.

S: So if there's only one thing out there to eat in the ecosystem, then everyone's going to have the same tooth anatomy.

S: And if there's a lot of different things to eat, then that's where you get a lot of diversity in the tooth anatomy.

C: Yeah, and that reflects your niche.

C: Or for people who want to write in and complain about our pronunciation, the niche.

C: But yeah, it's true.

C: It's so much more than just anatomy.

C: It is ecology.

C: Your teeth reflect your ecology, which is a really interesting concept.

C: And I think what really struck me as I was looking at this article, the actual source article is how complicated the scientific endeavor of understanding evolution over large timescales really is.

C: Because it comes down to genetic analysis.

C: It comes down to geographic analysis.

C: It comes down to morphology.

C: It comes down to ecology.

C: All of these different factors have to be modeled together.

S: Well, it's not just that, Cara.

S: It's not just the complexity of the details that we're looking at.

S: It's also the fact of the patchiness of the fossil record.

S: We're getting glimpses in different locations and time periods represented by specific fossil beds that we find.

S: And so it's really challenging to do statistical analysis.

S: It's not like we have a continuous fossil record of like most African species over this period of time.

S: How could we not notice that they mostly went away?

S: Because we're just trying to statistically pull this out of the data from these just patchy little moments, glimpses, flashbulbs in this long, long history.

C: And you're right.

C: They're patchy both kind of horizontally in time and vertically in time.

C: So at any given moment, or let's say over the length of a lot of time, we are only seeing maybe something happening this many million years and then a few hundred thousand after and then maybe 10,000 after and then another 2 million after.

C: But then also if you're looking horizontally across time, at any given time, there are countless species that we never will know about because they never left a trace.

C: And that's something that's almost difficult for us to wrap our heads around.

C: We have this sort of paleontological idea that we sort of know about everything that ever existed because we've got evidence from it.

C: But there are literal whole species that never fossilized.

S: And one last thing before we go on.

S: Whales are in the order Arteodactyla.

S: They're in the infraorder Cetacea.

S: And the Archaeoceti is a parvorder, which is one notch below infraorder.

S: Yeah, it's an order, then infraorder, then parvorder.

S: And that's when you get down to the Archaeoceti.

C: Wow, I didn't even...

C: Gosh, I didn't even know that they were subdivided that deeply.

S: When you think about it, they came up with class, order, and gene and species.

S: Yeah, that's an old distinction.

S: It's a finite number of taxonomical levels.

S: But what if you need many more levels?

S: They had to keep inventing these different levels to put, to slice in their superorder and infraorder and parvorder to just to fit, you have to create enough levels to accommodate whatever is the reality out there.

Strange Radio Waves (20:36)

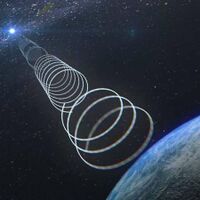

S: All right, Bob, always intrigued by radio waves we can't identify coming from space.

S: Tell me, tell us about this new one.

B: Yeah, so this was unusual and extremely variable radio signals coming from near the center of our galaxy.

B: And it's been detected by ASCAP and it has our astronomy boffins scratching their heads.

B: Is it a whole new type of stellar object?

B: And what the hell is ASCAP?

B: I will answer fully at least half of these questions if you keep listening.

B: The teams contributing to this discovery come from all over the world.

B: Australia's National Science Agency, CSIRO.

B: I haven't heard that one before.

B: C-S-I-R-O.

B: I'm not sure how you pronounce that.

B: But also from Germany, United States, South Africa, Spain, France, Canada, all over.

B: And if you want to read details, go to the Astrophysical Journal.

B: So an object emitting variable light.

B: So in space, that's pretty common, right?

B: All over the universe.

B: Supernovae, pulsars, fast radio bursts, Cepheid variables.

B: But what ASCAP spotted doesn't fit anything we've seen before.

B: Now ASCAP, as I've mentioned it and promised you, stands for Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder.

B: And it really is a marvel.

B: It's a radio telescope in Western Australia.

B: It consists of 36 dish antennas, each one 12 meters in diameter, and it covers six square kilometers and they all work together, much like a much larger, more sensitive telescope.

B: They all can pull their information as if they were that big.

B: Now ASCAP generates data at an incredible rate.

B: Guess how incredible it is?

B: 100 trillion bits per second.

B: Let me say that again.

B: 100 trillion bits a second.

B: Wow.

B: That exceeds the data and the rate of Australia's entire internet traffic.

B: Wow.

B: Wow.

B: Oh my God.

B: Now one of the reasons it generates so much data is that instead of homing in on a few objects at a time and really taking a solid look at them, it can catalog, for example, millions of galaxies at a time.

B: So the information is coming in fast and furious.

B: Much better movie series than I thought, by the way.

B: Now before this, ASCAP had already found other mysterious objects, including something with an awesome name, ORCS.

B: And that stands for Odd Radio Circles.

B: Or-chay.

B: Or-chay.

B: So ORCS, Odd Radio Circles.

B: I hadn't heard of those.

B: Essentially, those are giant circles of faint radio light that ASCAP has discovered.

B: Another kind of mysterious thing.

B: So what it found more recently, though, was even, it was even mysteriouser.

B: More mysterious.

B: No known objects could account for the radio light that they were seeing.

B: So first of all was the brightness.

B: The radio brightness varied by unexpected amounts.

B: Huge leaps by a factor of 100 at times.

B: Just really amazingly different and very quick.

B: And at times the signal would disappear like that.

B: TWAP!

B: It was like very quick.

B: It was just totally going away.

B: Didn't make any sense.

B: Ziteng Wang, lead author of the new study, said, the brightness of the object also varies dramatically, and the signal switches on and off apparently at random.

B: We've never seen anything like it.

B: And quote after quote kind of says a similar thing.

B: Wow, never saw that before.

B: The hell could that be?

B: Right?

B: What was more interesting, though, was the extreme polarization of the radio waves from these mysterious objects.

B: So this is a phenomenon that many of you have heard of, I'm sure.

B: The term electromagnetic radiation itself is the key, I think, to what happens during polarization because light is made up of an oscillating electric field, which is perpendicular to an oscillating magnetic field, electromagnetic.

B: So now both of those fields are also perpendicular to the direction of the movement.

B: Okay?

B: So electric field, magnetic are perpendicular, and those two are perpendicular to the motion of the light.

B: So that's what a transverse wave is.

B: It's the definition of a transverse wave.

B: Now in comparison, sound is a longitudinal wave, right?

B: Since the displaced particles move in the same direction of propagation, right?

B: You got the compressions and rarefactions of sound in a gas or a liquid.

B: Those are longitudinal waves.

B: So light normally consists of these oscillating fields that happen in any direction, right?

B: As long as it's perpendicular to the motion.

B: But you've got 360 degrees to choose from that you could kind of fluctuate along.

B: So imagine a taut string is the direction of light.

B: That oscillating electric field can go up, down, and then towards you or away from you or any angle in between, countless angles in between.

B: So now certain materials can remove all of those degrees, like all of those angles, except for one for the electric field oscillation.

B: So just one plane remains, and that's exactly what a polarized lens, polarized sunglasses do.

B: It reduces the glare because it's filtering the light, letting through only one plane of that electric field oscillating that gets through.

B: So this radio light near the center of the galaxy was highly, highly polarized, very unexpected.

B: What do you do in this situation?

B: We have a very powerful, very fast new tool that's finding some anomalies.

B: So let's check other telescopes, right?

B: Because that's just good science.

B: So ASCAP, it is a relatively new telescope.

B: And among other possibilities, their observations could certainly have been an artifact, right?

B: Based on their specific instrumentation or their software.

B: I mean, we have found scientific discoveries that were anomalies that was because of specific instrumentation.

B: Do you remember that neutrino discovery that had a problem because something was unplugged?

B: Do you remember that one?

B: Oh my God.

B: Oh my God.

B: So you got to check other instruments.

B: So they went to the Park Observatory, which is a radio telescope in New South Wales, Australia.

B: They didn't see anything.

B: They must have been a little nervous at that point.

B: But then they went to the very sensitive Meerkat radio telescope in South Africa, which is a great name, by the way, Meerkat.

B: And they did see it again.

B: So that was good.

B: It was very brief, but it did confirm the ASCAP observation.

B: So I'm sure they kind of maybe, you know, breathed a sigh of relief at that point.

B: So yeah, so this is definitely something that's there.

B: It was happening.

B: So of course, during this process, they're thinking, well, what is this thing?

B: What kind of source could produce the kind of light that they were observing?

B: So they started ruling out possibilities quite unlike a UFO enthusiast ruling out plausible explanations for lights in the night sky.

B: They consider things like flaring stars and close eclipsing binaries.

B: And they decided that, well, that's very, very unlikely because they kind of have X-rays and near infrared radiation associated with it.

B: And these observations did not have that.

B: They looked at pulsars, but pulsars didn't make any sense either because they're very regular and periodic, right?

B: These new observations varied all over the place.

B: It was fading in, fading out.

B: And then there was three months where it completely stopped.

B: So that's definitely not pulsar activity.

B: They also looked at supernovae, X-ray, binaries, and even one of my favorite phenomena, which what is it, what is it?

B: Nevermind.

B: Gamma ray bursts.

B: And they ruled all of those out.

B: So what is it?

B: They don't know.

B: But they did notice one connection.

B: There was one connection that the researchers noted to another mysterious signal that was observed near the galactic center.

B: And these are not called orcs.

B: What do you think they were called?

B: Goblins.

B: They were called hobbits, which stands for, I totally made that up.

B: It was not hobbits.

B: Because if you thought one news item would have two acronym nods to Lord of the Rings, and you're just being really silly because that would be way too cool.

B: The name of the other mysterious signals observed isn't even an acronym.

B: It's an initialism, GCRT, for galactic center radio transients.

B: So it sounds kind of similar.

B: It deals with radio signals and near the galactic core.

B: But so there's some similarities, but there's some differences as well.

B: So that's not a home run either.

B: Although both of those sightings were kind of mysterious.

B: So who knows what it eventually is going to be?

B: What can we expect from the future of these signals?

B: I'll end with a quote from Professor Tara Murphy from the Sydney Institute of Astronomy and the School of Physics.

B: She said, within the next decade, the transcontinental square kilometer array radio telescope will come online.

B: It will be able to make sensitive maps of the sky every day.

B: We expect the power of this telescope will help us solve mysteries such as this latest discovery, but it will also open up vast new swaths of the cosmos to exploration in the radio spectrum.

B: So I think we're going to see a lot of great radio spectrum observations, not only with ASCAP, but also with this transcontinental square kilometer array.

B: That sounds fascinating.

B: So that's what we got.

B: So new discoveries from the ASCAP.

B: And I expect a lot out of this instrument.

B: It sounds amazing.

B: Keep an eye out for any new discoveries and any new hints at what this thing is towards the center of our galaxy.

S: Bob, you know what I found surprising?

S: Yes, you know what?

S: That none of the reporting mentioned aliens.

S: Oh, yeah, that is kind of surprising.

B: Yeah, I didn't come across it either.

B: Right?

S: You would think, is it aliens?

S: Like, isn't it?

S: Wasn't that in the opening paragraph?

S: I was actually, you know, proud that they resisted going there.

S: But it's kind of, I was expecting that to come up and it just never came up.

B: Yeah.

B: I mean, could it be encoded, some subtly encoded information?

B: Probably not.

S: Because even...

S: What if the information is encoded in the rotating polarization?

S: That'd be an interesting way to encode information.

B: Yeah, it's kind of like, some of it's at least, it's circularly polarized.

B: So it's kind of like, it goes, the electric field is oscillating in one direction, but the direction it's pointing to kind of drifts over time.

B: The movement, if the movement was complicated enough to encode information, I think they might have noticed.

B: But who knows?

B: Who knows?

S: I think...

S: Or the random on-off sequence.

C: Yeah, but that doesn't usually stop somebody from going, but wait, aliens.

C: True, true.

B: That's true.

B: That's the first thing that they say.

B: But the on-off though, Steve, would be a very low bit rate.

B: But I think we could potentially be just bathed in information that's subtly encoded in something that we aren't even detecting.

B: So at some point, we'll have some new instrument and they'll be like, oh boy, Encyclopedia Galactica has been running by us all this time, we never even noticed it.

B: Possibly.

B: That would be very cool.

C: I can always dream.

C: Ooh, like in Arrival.

C: Like the sort of ingredients for time or whatever.

Plant Molecular Farming (30:54)

S: All right, Jay, we're going to learn a new term here.

S: What is plant molecular farming?

J: As the global population of our planet grows, some say way too fast, our needs for food increases with it, right along with it, right?

J: So humanity has and still is always trying to make food production more efficient and sustainable.

J: So today we also want it to be environmentally friendly.

J: So when it comes to the future of food production, humanity is going to have to use biotechnology to help us reach our food needs.

J: So this same technology is successfully used in the fields of medicine.

J: It's also used in industries to produce genetically modified organisms like bacteria and yeasts.

J: When a huge amount of specific proteins are needed, we turn to biotechnology.

J: Insulin, for example, is created by yeast that was bioengineered.

J: Another industry that benefits from GMO organisms is the cheese industry, if you could believe it.

J: Big cheese, it's what we call it.

J: So this relies on enzymes, right?

J: The cheese needs enzymes and we create these enzymes using GMO organisms.

J: And an up and coming GMO technology that we're likely to heavily rely on is what Steve said earlier that this is plant molecular farming.

J: This is similar to engineered bacteria, but it's an entire plant.

J: It's not just growing bacteria.

J: So the idea is that the plant itself has been genetically modified to produce a specific substance that can be found in its leaves or in its seeds.

J: Barley and tobacco are two examples that are in use today.

J: So a GMO plant can now be used as a self-replicating biofactory.

C: Think about that.

C: Oh, I see.

C: So the difference, because we've been genetically modifying plants for a long time.

C: So you're saying instead of genetically modifying a plant to be a food source, we're genetically modifying it to then be able to utilize some sort of like chemical that it's producing in industry.

J: Yeah, the leaves, for example, or the seeds will contain a chemical that we need and it could be...

C: I mean, don't we already do that with corn and ethanol?

J: Yeah, absolutely.

J: Biofuels is on the list.

J: We've modified cotton to be a better textile.

J: But now we're getting into like specifically pulling out certain chemistry out of a plant, engineering it to give us something specific.

J: And then the plant will propagate itself, which lowers the cost of production and everything.

J: So this is an incredible use of this technology.

J: We have modified a barley plant to produce proteins that are used to grow meat stem cells.

J: So these proteins are called growth factors and they are 80% of the cost of making lab-grown meat.

J: That's an incredible amount of cost right there.

J: And if we can use barley to mass produce the proteins that we need to grow lab-grown meat safely and inexpensively, the entire cost of lab-grown meat could and will significantly drop.

J: Now, anti-GMO activists won't like the fact that GMO technology is used to make lab-grown meat.

J: But if lab-grown meat makes it possible to significantly lower the animal-based meat industry, how many animals that we kill every year for meat, how can they possibly object?

J: Well, some of them will, I'm sure.

J: But I think for the most part, we're moving in a direction where even anti-GMO people are going to have to look at it and go, this is a damn good thing.

J: We're not slaughtering millions of animals every year to feed humanity.

J: We're using GMO technology to create the proteins that we need to grow the lab-grown meat.

C: Well, it's a funny conundrum because we're already seeing it with Impossible.

C: So you know that Impossible meat has something called leghemoglobin, which is what gives it that meaty flavor, although it's completely plant-based.

C: There's no animal products, but it bleeds.

C: But it's not real blood.

C: It's leghemoglobin that comes from usually soy.

C: But they realized, we can't produce enough soy.

C: Like that's a massive waste.

C: So they were like, we can just genetically engineer yeast to make leghemoglobin.

C: And then we just use that recipe.

C: So anybody who's eating Impossible is already eating genetically engineered leghemoglobin from yeast.

J: So Cara, let me ask you a question.

J: So what do you do if you're an anti-GMO activist who loves Hawaiian papayas?

C: Right.

C: I mean, I remember that Kevin Folta used to always say, the state of Florida is going to love GM once they can no longer grow oranges because of citrus greening.

C: The minute that a genetically modified orange is the only orange that's available, people are going to really change their tunes on GM because they like orange juice more than they hate GMs.

C: Exactly.

J: Exactly.

J: They got to have what they got to have.

J: And this technology is a lifesaver.

S: Well, and here's the advantage.

S: Now we use recombinant bacteria or yeast or microorganisms like that.

S: The plant-based platforms like tobacco or barley have one big advantage, and that is you don't need a bioreactor in order to grow the cell.

S: If you're growing bacteria to harvest a drug or growing yeast to harvest an enzyme or whatever, that needs a bioreactor.

S: They're massively expensive to build and maintain, and they're responsible for a lot of the cost.

S: And or you could just grow barley and harvest the seeds.

C: But at the same time, it looks like it's a trade-off, right?

C: Like, yes, it's very expensive to do it in a bioreactor, but it also takes up barely any space because you're talking about microorganisms as opposed to having to grow a shitload of barley to then extract a protein or some chemical out of the barley and then what, like leave the barley, leave all the other portions of the plant on the vine?

C: That's the part I don't really get.

C: Like if we could use a whole plant model, that would be much more sustainable.

S: Yeah, it's going to come down to a couple of things.

S: Like, yeah, you have to compare those costs.

S: What's the land use cost?

S: You know, what is the cost of growing and how much do you need?

S: If you don't need that much, you know, if you just need 100 acres worth of barley or whatever for whatever you need the protein for, it's like a round off in terms of our farmland.

S: Yeah, what's the density?

S: Yeah, so it depends on what we're using it for.

S: And then what would be the price advantage not to need to buy a reactor?

S: For lab grown meat, unfortunately, the growing of the meat requires a bioreactor and that's a major cost of that leather 20%, you know, but the 80% right now is making the growth factors.

S: If we could knock that price down by an order of magnitude by using a barley platform rather than, you know, a microorganism that requires its own bioreactors, that could bring the cost of lab grown meat down into the realm of consumer reach.

S: We'll see.

S: It still may be very expensive, even without this component to it.

S: But again, there may be other applications completely different where it's like, yeah, who knows?

S: Maybe we'll grow our insulin this way or something.

S: You know, we'll see if that could, but it's a, once they kind of perfect the platform itself, and again, the other advantage of barley is that most of the non-target proteins are going to be in the coat, you know, the shell, and then the interior seeds going to be all payoff, you know.

S: Yeah, the purification process could be a lot easier.

S: So it could just be a very useful platform for growing industrial proteins, enzymes, etc.

S: Growth factors for whatever we need them for, for medical uses, for agricultural uses, whatever, food production.

S: And we'll see how it goes, but I think it's a nice other option to have with some significant advantages that we can't ignore.

J: Yeah, without a doubt.

Neurofeedback Headbands (39:43)

S: Our one more news item, this is about neurofeedback headbands for stress reduction and improving, of course, athletic performance.

S: Because that's what all things do, right?

S: So you guys heard about this?

S: There's a recent BBC article about it.

S: We got a lot of email.

S: A lot of people asking me, hey, is this real?

C: Well, and it's also not new.

C: Like there have been versions of this.

S: No, no.

S: When I wrote about it on my blog, somebody found an article by Barry Beierstein from 1985 debunking this, 1985.

S: There's been research since then, but the bottom line story hasn't really changed very much.

S: So the idea is of neurofeedback is using essentially an EEG, measuring your brainwaves in order to provide feedback to help people learn to either meditate or relax or enter a calm mental

C: state. Or it helps that sometimes people will use neurofeedback clinically for ADHD.

C: So like look at the light and then when your mind starts to wander, the light gets larger.

C: So then now I need to look back at the light and it gets smaller and it's like this feedback

S: loop. Yeah.

S: So the idea of providing feedback to people to help them address their attention is fine because attention is a high energy voluntary thing.

S: It's using your frontal lobes.

C: And it's easy to measure on EEG.

S: And yeah, it's easy to measure frontal lobe activity on EEG and providing feedback is a way for, it seems to help people learn to relax or meditate.

S: But it's not magical, right?

S: It doesn't do anything special.

S: You're not training your brainwaves or entering in some paranormal state or anything like that.

S: The claims get like ridiculous at the fringes.

S: But the core claim that, yeah, you'll learn a little bit quicker how to relax is supported by research.

S: But that's not saying much, you know, that...

C: It reminds me, Steve, of EMDR.

C: Oh yeah.

C: It's a gimmick.

C: Like it's an evidence-based, yeah, it's an evidence-based approach because we know that people who go into the clinic and use EMDR tend to have better outcomes for their trauma.

C: But it's not because they're moving their eyes.

C: That's not the magic ingredient here.

C: The ingredient is that they're getting therapy.

C: Exactly.

C: They're in there getting therapy for their trauma.

C: And maybe it's something about focusing your attention somewhere that's not directly on the trauma that sort of allows you to approach things so that they're not quite as confrontational.

C: But you could do that with anything.

C: You could do it with sock puppets.

S: Right.

S: So the question is, is the neurofeedback part of this more gimmicky or is it somehow central to the beneficial effect?

S: I am of the opinion, looking at the research, that it's gimmicky.

S: But again, if you're just saying it is a way to help people train to relax better, fine.

S: And again, I also discussed and wrote about meditation before where it's poorly defined and I'm not even convinced that it's anything more than, again, just relaxation, just a way of getting people to relax or to focus in such a way that it reduces their stress levels.

S: And so at the end of the day, this is all about reducing stress.

S: And there's, I think, probably multiple methods of getting people to do that.

S: You know, their mental stress.

S: The research is a little tricky because like how do you...

S: What's the paradigm, right?

S: Like, Cara, you and I talk a lot about what's the research paradigm?

S: You say stress, but how do you operationalize that in a study?

S: So what they do is they give people a challenging mental task.

S: That's their stress.

S: The question is, is that a good model?

S: Is that a good paradigm for stress when we're talking about an athlete, you know, before a big game or whatever.

C: Or somebody who's dealing with chronic stress.

C: It's a completely different thing.

S: Exactly.

S: So it's not a great model probably, but it's what we got, right?

S: Stress is a convenient way to like on demand create mental stress in your subjects.

S: So but I would argue when it's not really clear how generalizable these results are to other so-called stressful situations.

S: So the other question is, can the EEG measure this type of mental stress?

S: And yeah, so the answer is basically yes.

S: But what it's really measuring is just your...

S: If you close your eyes, you get the alpha wave activity, which is essentially the baseline activity of your visual cortex when it's not being stimulated.

S: And when your mind, your brain is more active, you get more of a mixed waves and theta waves thrown in there.

S: But that's especially when your eyes are open.

C: Yeah, to be clear, EEG waves are not very specific.

C: Like we know...

C: They're not.

C: They're not as awake when somebody's asleep, when somebody's eyes are closed, when somebody's having a seizure, but it's a very hard to...

C: When they're drowsy.

C: Yeah, but it's hard to kind of know what's going on in all the noise otherwise.

C: Right.

S: And you know if it's symmetrical, right?

S: If all the parts of the brain are working well or if there's a deficit on one side or the other.

S: All right.

S: So but now there's a bunch of companies that have these neurofeedback headbands that they're making all kinds of claims for.

S: And the question is, does the research that we have that shows that, yeah, you can tell something about someone's state from their EEG and yeah, neurofeedback can help people relax maybe quicker.

S: Can you extrapolate from that to these actual devices on the market that make all kinds of claims about like this will improve your athletic performance if you use it before a game?

S: And that's where I think the claims go off the rails.

C: Also the EEG itself, like this idea that there's something magic in the brain waves as opposed to you could get the same thing measuring heart rate.

S: Yeah, but EEG is very sexy.

S: Yeah, totally.

C: What I...

C: Looking at brain waves versus heart rate, you're probably going to see a lot of crossover there.

C: You could probably just as easily predict somebody's stress state based on their resting heart rate as you could based on the brain waves.

C: Yeah, or blood pressure or galvanic skin response.

C: All these things we've been doing for decades.

S: Decades.

S: Now get this, this is a quote from an article about this.

S: Max Newland, president of BrainCo, explains that the headband uses an AI software algorithm to monitor 1,250 and then in quotes, data points in a person's brain wave signals.

S: That's a lot of data points, right?

S: So what are they actually measuring?

S: There certainly aren't 1,250 leads or even channels, which a channel is a difference between two leads.

S: And I doubt they're looking at individual spikes.

S: What does that even mean?

S: That's like they put the data points in quotes.

S: Is that a temporal thing?

S: Are they saying like over some arbitrary period of time?

C: Oh yeah, because then they could get as many as they want.

S: Yeah, they can get as many as they want.

S: They could just...

C: Depending on the refresher rate.

S: They could just measure a fast computer, which you know, having a fast computer and a small device is not a big deal.

S: But the question is, what does that resolution mean?

S: It sounds impressive.

S: Ooh, that's getting a lot of information.

S: But that resolution is meaningless.

S: It's meaningless.

S: What does that tell you about a person's EEG?

S: That super high temporal resolution, does it even matter?

S: I file that under useless precision.

S: You know?

S: Yeah, marketing.

S: Yeah.

S: It doesn't necessarily improve the utility of the information we can get out of that EEG or the feedback that's being provided to the person using it.

S: Which just superficially sounds very impressive.

S: It's probably what I would consider to be zero clinical value.

S: Now but of course the product's being sold with all kinds of claims.

S: You know, and again, the ubiquitous one that for athletes because they're so easy to game, you know, to get the placebo effect for athletic performance is huge.

S: But there aren't any like well conducted, blinded, you know, placebo controlled trials with a reasonable placebo arm showing that the headbands itself provide any benefit above and beyond just doing relaxation or meditation or even just doing it with a device that's not working just to see if there's a placebo effect from putting this device on their head.

C: Which is silly because it's the easiest paradigm to do.

C: You probably can't feel anything from this damn thing.

C: So put one that's on and put one that's off.

S: Yeah, exactly.

C: That's providing random feedback.

C: Like this is like a science fair experiment for a second grader.

S: So but they don't do it, Cara, because they don't want to do it.

S: Why would you do a study that could prove your product doesn't work?

S: All right, but I did find only one study that was an actual comparison like to a placebo, to another treatment group where you could make some kind of conclusion about whether or not it's working.

S: This was of a different device but a similar commercial headband EEG feedback device and using heart rate variability as a measure of stress.

S: And they found zero difference between using the device and no observable difference in the two conditions with or without the headband.

S: So the device didn't work in the one study that really was testing whether or not it, you know, similar devices like that do work.

C: So these companies are going to have to change their name to the placebo.

C: Wear it.

C: Smarter, faster, better.

C: Yeah, right.

S: Not a lot of data, but not enough to say that was this a technical failure of that one device or is the whole concept flawed?

S: Right.

S: The whole concept is flawed.

S: But you know, we would need more and more data to demonstrate that.

S: So I just think it's a, you know, it's a commercial con in a way where it's just focusing on the whiz bang technology and with like, you know, how good the computers are and we're using AI with all these data points, but really doesn't mean anything plausibly translate into anything clinical.

S: Rather than just focusing on the low tech, here are some basic relaxation techniques or some basic techniques to help you focus your attention or maybe not be focusing on the things you shouldn't be focusing on or whatever.

S: It's a grounding exercise.

C: It's like anybody who's ever gone to a therapist for anxiety has learned these basic exercises.

S: Yeah, but there's not a lot of money to be made from that.

S: Right.

S: There is to have this gee whiz headband you put on that is measuring 1,250 data points, whatever that means.

C: Which to me, it's like, I'd much rather do a 5-4-3-2-1 grounding exercise or like learn how to do some good diaphragmatic breathing.

C: Because you can do that in the middle of like, I don't know, a board meeting.

C: You can't just like whip out your headset and be like, I'm feeling quite panicky.

C: I'm going to put on my headset in the middle of a lecture.

C: Some people will be like, what are you doing?

S: So yeah, I think it's made for marketing, not for like actual utility.

S: And it's kind of dubious at multiple levels.

Who's That Noisy? (50:51)

S: All right, Jay, you've got to get us caught up.

S: You're two weeks behind on Who's That Noisy.

J: Oh boy.

J: All right, guys, last week I played this noisy.

J: What the hell is this?

C: Jay, I love how you're so on autopilot because you've been doing this for so long that you literally just said, last week I played this noisy.

B: Yeah, yep, I noticed that too.

J: It was many weeks ago, you're right.

J: It is, it's deeply ingrained.

S: You just go shift over to last time, that way it's nonspecific and it always works.

C: It's like good to see you instead of nice to meet you.

C: Always works in a setting where you may not remember if you've met the person before.

J: All right, would any of you guys like to make a guess before I move forward?

C: Something starting.

S: It's an electric car on a racetrack.

B: Jay, I think it's a sound effect in the meat market section of my haunted house.

B: No?

J: All right, so I have a listener who I'm going to apologize ahead of time.

J: I believe that the person's name is pronounced Jacopo Gilly.

J: He says, hi guys, I think I am quite sure this week first time emailing, not first time wondering about your noises.

J: I think that the sound of a disc brake clamp test, which is brought up to failure being more specific, I think it's from the video where Bugatti tests topology optimized brake clamps for Bugatti Veyron.

J: He goes on to say he's an Italian mechanical engineer.

J: He lives in Sweden in Malmo and he does these types of simulations.

J: Very cool.

J: This is not correct, but there is a little bit of a connection, a very loose connection here you'll see in a minute, but thank you for sending that in.

J: Another listener named Baker Deeds said, hey guys, I've been listening.

J: I've been a listener for several years, but this is my first time guessing the noisy.

J: I believe the noisy for this week is a gauss gun charging up and being fired or a rail gun depending on terminology.

J: Very cool.

J: I've never heard that.

J: I want to hear it.

J: I'm sure that they make a ton of noise and it must be cool, but that is not correct.

J: I have another guest here.

J: This is from Joe Vanden Eden.

J: This is a Rolls Royce Trent 1000 turbofan jet engine suffering a bearing failure on startup.

J: Very specific.

J: We have a winner from last week or two weeks ago and that winner is Joshua Covey.

J: He said, howdy Jay.

J: First time guesser from Austin, Texas.

J: I started listening right after the start of the pandemic.

J: He said this feels a little cheaty, but I know of Brad Philpot as he is a fairly regular contributor to missed apex podcast, the F1 podcast.

J: And he said, if there is a Richard G aka spanners that knows every tiny detail about the noisy, I would be a bit suspicious.

J: So he says, anyway, my guess without doing too much research would be that the noisy is the sound of a modern Le Mans car accelerating from a standstill starting in second gear.

J: They accelerate all the way through second gear, change to third, then deaccelerate.

J: Very cool.

J: So he hit the nail on the head.

J: Now going back to the original person who sent it in, which happens to be Bradley Philpot and is a frequent guest on the missed apex formula one podcast.

J: He sent in this noisy.

J: He said it's a modern hybrid Le Mans 24 hour race car, which must run purely on electric power when it's in the pit lane, but then it's allowed to switch over to its petrol powered engine as soon as it leaves the pit lane.

J: So let me play that to you again.

J: Now, so what you're hearing is the Le Mans 24 hour race.

J: This is the hybrid Le Mans car that has an electric motor and a petrol motor, and it's the electric motor that starts.

None Ready?

J: So that second noise you hear is the gasoline engine taking over.

J: Very cool, very interesting sound, and it is unique.

S: So Jay, I was right.

S: It was an electric car.

S: I just got the scale a little off.

C: And I was right.

C: It's something starting.

C: Exactly.

J: You guys really did great this week.

J: Four for Bob.

J: Bob didn't even try, which is lame.

C: By the way, Jay, that description you gave, you could have made up 90% of those words and I would be blissfully unaware.

C: I know.

C: That was some turbo encabulator shit right there.

J: Without a doubt.

J: I love that kind of stuff because there are hidden worlds, secret worlds that we know nothing about all around us.

J: There are people who are experts with cars that drive 300 miles an hour, and they could throw out any jargon.

J: You would believe it.

J: All right.

New Noisy (55:31)

[resonating whir with intermittent loud and quiet vibrations]

J: I have a new noisy this week, and it came from a listener named Cappy Collins.

J: Cappy, you have a superhero name.

J: I'm Cappy Collins.

J: By day and by night, I am whatever.

J: Okay.

J: Let's go on to that noisy.

J: How cool is that?

J: If you think you know what this week's noisy is, or if you heard a noisy that you need to make me aware of, you can email me at wtn at the skeptics guide.org.

Announcements (56:26)

J: All right, Steve.

J: I got a few quick clarifications and announcements.

J: Yes.

J: All right.

J: The extravaganza, which is happening on November 18th in Denver, is still sold out, but we do have two private shows.

J: These are live podcast recordings.

J: One of them is happening on the 19th.

J: That's in Denver.

J: Another one is happening on the 20th.

J: That's in Fort Collins.

J: These are all places in the state of Colorado in the United States.

J: If you are interested, go to the skeptics guide.org forward slash events for the details on how to purchase tickets for those two remaining events.

J: The Denver private show is getting close to max capacity.

J: So if you're interested, you should move quickly.

Email/Name That Logical Fallacy (57:06)

_consider_using_block_quotes_for_emails_read_aloud_in_this_segment_ with_reduced_spacing_for_long_chunks –

S: All right.

S: We're going to do an email slash name that logical fallacy because I do think that it's an interesting question that also leads to a discussion about critical thinking that has been coming up a lot recently.

S: So the email, I'm not going to give the person's name because I'm going to use it as an example.

S: They write, a 2007 study showed that humans and rhesus monkeys share about 93% of their DNA.

S: Similarly, the fossil record has identified ancestors common to both humans and monkeys, such as an as yet unnamed primate fossil from Myanmar found in 2009.

S: Humans are actually more closely related to chimpanzees and other apes, but DNA evidence shows that we didn't evolve from them.

S: Apes and humans share between 98 and 99% of DNA, suggesting that we shared a common ancestor around 6 million years ago.

S: My question is simple.

S: When we do ancestry DNA tests, why don't this common DNA show up as rhesus chimpanzees or other DNA in our test printouts?

S: So the guy is saying when you get your printout of your DNA and where it's from, why doesn't

C: it say? Why don't we have animal DNA?

S: Yeah.

S: Well, this is rhesus DNA and this is chimpanzee DNA.

S: How come it doesn't say that?

C: Well, I think he answered his own question.

C: Didn't he?

C: Like the fact that we all have a common ancestor, we all share a certain amount of DNA with chimpanzees.

C: We have it in common.

C: It doesn't mean that we came from chimpanzees.

C: We do, certain ancestry companies will put the percentage of Denisovan or the percentage of Neanderthal DNA.

S: Everything you just said is correct.

S: Although I was more interested in a different aspect of this email because to me it's like, the question is what is the critical thinking error that the question is making?

S: There's some error in the question itself.

S: And I wanted to wrap my head around that.

S: So what do you think, Cara?

S: I think what I came up with is a little tangential.

S: This person's making this mistake.

S: It's not a great example of it, but I think it's the core of what their error is.

S: It's sort of a logical fallacy.

S: It's not one that we have on our list, but it probably could be added.

C: The weird thing is it sounds like the question came from a different person than the previous explanation because they showed a really-

S: That's because they're making a mistake that you're not making. And so you can't understand why they- Okay.

S: How did they get to that question from that premise?

C: Right, because their premise is like accurate and then they make a left turn.

S: Their premise is accurate, but then they make this leap to the question, and that's what I'm focusing on.

S: How did they make that leap?

S: What's the- Yeah, where's the gap?

S: What do you guys think?

S: Can you identify some kind of intellectual error in that leap that they made?

S: Are they thinking too granularly?

S: What do you mean by that?

B: Well, I mean, we share genes with like squid and other animals.

C: I get what you're saying, Bob, though.

C: It's almost like they understand that there's a linearity to evolution, but then in the last question, they're saying, what percentage of all these different creatures am I?

C: And it's like, that's not how evolution works.

S: Let me float an idea and then see if this helps you understand what their intellectual problem is.

S: I think what they're making is a mistake of essentialism.

S: Now essentialism is a very common quote unquote logical fallacy, like informal logical fallacy, but it's a way of thinking that really is like an unstated major premise of a lot of people's thinking.

S: It's like if you're being hyper-reductionist and you don't even know you're being hyper-reductionist.

S: I once had somebody say to me that all human history can be understood as an attempt to maximize our dopamine in our brain.

S: Like really?

S: You really think that?

S: Yeah.

S: Or like another good example of reductionism is to say that humans are a way for genes to reproduce themselves.

S: It's like, OK, that's sort of true, but it doesn't capture everything about being a human.

S: It's a framing.

S: It's a super-reductionist framing that doesn't really capture all the different various aspects of biology.

S: To say it's all about genes making more copies of themselves, no, it's actually a lot more than that.

C: So I think— Can you describe their mistake, this reductionist mistake?

S: So I think—no, they're making an essentialist mistake.

S: Oh, sorry, this essentialist mistake.

S: Reductionism is when you think of categories as discrete entities.

S: Like there is something essential about being a chimpanzee.

C: This is why earlier in the show you said we were going to talk about this later.

C: Yes, exactly.

C: It's like there's a whole book, guys.

C: There's an amazing book by a woman named Lulu Miller, a great science writer.

C: She won a bunch of awards for it called Why Fish Don't Exist.

C: And it grapples with this very problem of taxonomy and why do we put this in this bucket and that in that bucket when this is half in this bucket and half in that bucket?

C: And it's a human-made endeavor to try to categorize things, but things don't exist in natural

S: categories. Here's the answer to his question.

S: The reason these tests don't say this is rhesus monkey DNA is because there's no such thing as rhesus monkey DNA or chimpanzee DNA.

S: The DNA that we share with them, we share 60% of our DNA with bananas.

S: Does that mean we have quote unquote banana genes in us?

S: No, we have genes in us, some of which are relatively conserved with things that we're related to.

S: And the more basic the function of the gene, the more relatively conserved it will be for a longer period of time.

C: And so it's just- We share some percentage of our DNA with archaea.

C: Like if you go back far enough, we all came from the same common ancestor.

S: Yes, histones.

S: I think every living thing has the same histones, which are the proteins-

C: Rhizomes. Those are there everywhere.

S: Yeah, exactly.

S: It's so basic to biological function that we all have it.

S: And so this creeps into the GMO rhetoric where they go like, you don't want to put fish genes in a tomato.

S: There's no such thing as fish genes.

S: There's just genes.

S: And if you say, well, it's the genes that are in a fish, it's like, yes, but we share what 80% or 90% of our genes with fish.

C: Yeah, once you get to the animal level, it's really high.

C: It's actually chordates.

S: Yeah, vertebrae.

S: Yeah, it's going to be high.

S: Again, 60% with a banana.

B: That says it all right there.

S: That's what's on my mind.

S: But we tend to think about like there's chimp DNA and how come there isn't saying there's chimp DNA in humans?

S: Because yes, we have a lot of the same genes because we have a recent common ancestor.

S: There hasn't been enough that much time to build up differences in our DNA.

C: But we weren't created by humans having sex with chimps.

C: And that's where this is a really different scenario than why they can say there's this much Denisovan versus this much Neanderthal.

C: Because there's a good chance that our own human ancestors literally mated with chimps and Neanderthals.

S: Yeah, that's a completely different thing.

S: That's when you have mutations that occurred recently, which are unique to one population.

S: And you can say, well, this population at some point, one of the founders of this population had this mutation, and all of the individuals in this population share that mutation.

S: And if we have that mutation in us, it's because one of our ancestors had sex with one of their ancestors.

C: Yeah, it's how we can sort of type dog breeds in a way.

C: Because they're all dogs.

C: They're all the same species.

S: If there is anything that can be said to be chimpanzee DNA, it would be mutations that occurred in chimpanzees.

S: And only chimpanzees.

S: By definition, we would not have them.

C: At least...

C: And that's going to be in that 1.5%.

S: However, I would say, though, that we do have mutations that we share with chimpanzees.

S: And that's part of how we know that our ancestors and chimp ancestors were doing the nasty long after they, quote unquote, split.

S: Which gets me to another point, is that the very concept of a species is an essentialist logical fallacy.

S: Species don't exist either.

S: Because the notion of a species is really super fuzzy.

S: There's no one specific, clear way to delineate it.

S: Now, sometimes people get confused in a couple of ways.

S: One, they get confused by the illusion that a category is discrete just because all the related stuff doesn't exist anymore or we don't know about it.

S: So if you're at one end of an evolutionary branch and all of your closely related relatives died off, then it may seem like, oh, you're your own thing out there on your own.

S: But in order to get there, you have to leave a trail of ancestors that are a spectrum.

S: Species are a spectrum.

S: There's no sharp demarcation line.

S: And you can say, well, what about breeding when you don't crossbreed?

S: Well, but what if we occasionally crossbreed?

S: What if we exchange genes through an intermediary?

S: No matter what type of definition you come up with, you could break it.

S: And nature does break it.

C: Yeah, wolves and dogs can have viable offspring.

C: Yeah.

C: They're considered different species.

S: Well, they're actually not, but it's arbitrary.

S: Is a chihuahua and a wolf the same species?

S: Why would you consider them the same species?

S: They look so different.

S: Well, because, you know, they're genetically very similar.

S: Or anything we try to categorize, the categories break down because nature is messy and it tends to be more of a spectrum.

S: That's why, like, if you try to categorize everybody in the solar system as either a moon, a planet, or an asteroid, that works if you have a few...

C: What about X?

C: That breaks down.

S: Dwarf planets.

S: Is Charon, is Pluto's largest...

C: Planetesimals.

C: Yep.

C: That's why I love my Archaeopteryx statue that I have on my forearm.

C: People often ask me, why did you pick that out of all the different fossils?

C: And I'm like, because it's weird.

C: It doesn't...

C: It's like, it's sort of a bird dinosaur bird.

S: It's awesome.

S: I know.

S: Like, Dwayne Gish tried to say, either it's a dinosaur or it's a bird.

S: No, Mr. Gish.

S: It's so wrong.

S: It's literally not either of those.

S: It's in the middle.

S: You know nothing.

S: It's a bird dinosaur because it's, you know, it's like right in the middle of this transition from one to the other.

S: It's neither and both.

S: It's half of one and half of the other.

S: Yeah.

S: It breaks the category.

S: Literally.

S: I love it.

S: Yeah.

S: But the human brain likes to think in terms of discrete categories.

S: And we like to pretend that our categorization system, these boxes that we invent in order to help us understand and wrap our head around the universe, that they reflect reality when they don't.

S: Because reality is continuous and sloppy and messy and fuzzy at the edges.

Interview with Craig Good (1:09:27)

S: Let's go on.

S: We have an excellent interview with Craig Good about his book on food.

S: Let's go to that interview now.

S: We are joined now by Craig Good.

S: Craig, welcome back to the Skeptics Guide.

CG: It's great to be back and I love what you've done with this.

CG: Thank you.

CG: Did Bob pick the curtains?

CG: A quick back story.

J: Our virtual presence.

J: Because we know Craig.

J: We have a history friendship with Craig.

J: So I think, Craig, you first contacted us, I mean, God, it was probably like, what, 12 years ago at this point?

CG: Sure, something like that.

J: And Craig, you used to work at Pixar.

J: That's correct.

J: And Craig said something like, hey, if you guys get out here, and we were like, okay, we'll be there next week.

J: And we were like, immediately wanting to go and we got to see like a backstage tour of Pixar and it was one of the coolest things.

J: Yeah, it was incredible.

J: We will always remember you for that.

J: Thank you so much.

J: It was my pleasure.

S: That and then the free lesson you gave us on like the basics of camera, of camera, camera work, which we totally needed because we, you know, we're amateurs.

CG: If you don't know, how are you going to learn?

C: And of course, all of us being American, I can't help but think that us saying your name Craig over and over is driving all of our like UK and Australian listeners batty because they pronounce it Craig.

C: Craig.

B: Craig.

B: Really?

CG: Well, my old Craig, my Mexican family could never pronounce it at all.

C: So yeah, Craig.

C: It would come out Grek.

CG: Grek.

C: Oh, cute.

C: I love it.

S: So we're having you on the show this week to talk about a new book that you just published, which you kindly sent us copies of Relax and Enjoy Your Food.

S: All about just some really basic science-based nuts and bolts about nutrition, food, dieting, etc.

S: Yeah.

S: So give us a quick overview.

S: What's the book about?

CG: Why'd you write it?

CG: So the book is really about having a healthy relationship with food. And I wrote it because I figured somebody had to. Nobody else was. I used to spend a lot of time on Quora, which is this question and answer site because of my interest in food and the experience I had with my daughter helping them recover from anorexia. I had a lot of interest in food and I was answering some food questions and I started noticing that 98% of the questions were the same four or five questions over and over again. So that, well, that's kind of telling me that there's a screaming need out there to just, you know, clear away the crap and figure out what's basic, you know, and that it's, you know, science is complicated, but knowing how to eat really doesn't have to be. The consensus has been pretty solid on that for a long time.

S: Yeah.

S: I mean, I agree.

S: And we've said that a lot on the show.

S: It's actually quite simple.

S: For most people, you don't need to have a ton of information to be like 98% of the way there in terms of having a healthful diet. It's just, there's just not a lot of money to be made on telling people the same one paragraph of information over and over again. And so the self-help industry creates a lot of food, dieting advice just as a product, even though it's not based on science.

CG: That's what I refer to in the book as fear-based marketing. I was going to say, it preys on people's anxieties. Yeah.

CG: It really does.

CG: Yeah.

CG: Make people afraid of something and then say, and here's the solution.

J: Craig, did you find anything during your research that surprised you that you didn't know going into it?

CG: That's a really funny question because yes, when I was writing the book, it surprised me and today if I found it, it wouldn't surprise me at all.

CG: And that is that it wasn't surprising that most of the anti-GMO propaganda you hear is funded by Big Organic, but most of the rest of it is funded by Russia.

CG: What?

CG: Yeah.

CG: That really surprised me.

CG: It doesn't surprise me now because it's all of a piece with anti-vax and all the other just pot stirring that they've been doing.

CG: But that surprised me when I ran across it.

S: To what end?

S: I'll tell you because I've been encountering this for years.