SGU Episode 607: Difference between revisions

(auto skel, show notes) |

(Transcribed three segments) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Editing required | {{Editing required | ||

|transcription = y | |transcription = y | ||

|proof-reading = y | |||

|time-stamps = y | |time-stamps = y | ||

|formatting = y | |formatting = y | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

|cara = y <!-- leave blank if absent --> | |cara = y <!-- leave blank if absent --> | ||

|perry = <!-- leave blank if absent --> | |perry = <!-- leave blank if absent --> | ||

|guest1 = | |guest1 = GD: Greg Dash | ||

|guest2 = <!-- leave blank if no second guest --> | |guest2 = <!-- leave blank if no second guest --> | ||

|guest3 = <!-- leave blank if no third guest --> | |guest3 = <!-- leave blank if no third guest --> | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

* Jay talks to his son about where the cold comes from. | |||

''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ||

== Forgotten Superheroes of Science <small>()</small> == | == Forgotten Superheroes of Science <small>(11:06)</small> == | ||

* Wang Zhenyi: Wang Zhenyi 1768-97, was a pioneer women astronomer during the Qing dynasty | * Wang Zhenyi: Wang Zhenyi 1768-97, was a pioneer women astronomer during the Qing dynasty | ||

S: Bob, you're gonna start us off with a Forgotten Superhero of Science. | |||

B: Yes, for this week's Superheroes of Science, I'm goin' back a bit to the 1700's. I'll be covering Wang Zhenyi, 1768 to 1797. She was a pioneer woman astronomer in imperial China. She lived during the Qing dynasty, which is the last dynasty in imperial China. This was after the Ming dynasty, but before China became the Republic of China. | |||

During Zhenyi's life, there was a feudal system in China, so that only allowed the rich to be educated. You had to be wealthy, but of course you also had to be a wealthy man. Women were, as usual, relegated to the tasks of sewing, cooking, taking care of the kids, and education was deemed unworthy. They were unworthy of education. | |||

Luckily, Zhenyi's family were all scholars, and they saw no reason why she shouldn't be educated as well. And they focused specifically on astronomy and math, and she ran with it. Before too long, she was using physical models to explain how eclipses actually happened, instead of just thinking, like most people at the time, that they were just beautiful but mysterious. | |||

She also did things like explain and simply prove how the equinoxes move, lots of stuff like that. What I love though about Zhenyi was not the new discoveries or advances, but the way she communicated to those that came after her. She seemed to take a special focus on that specific thing. | |||

She mastered an important book at that time called ''Principles of Calculation'' by Mei Wending. And then she wrote the whole thing, but in simpler language, and made it available to others. She just took this important but kind of dense, complicated book, and rewrote the whole thing so that many more people could understand it. | |||

She also actually simplified division and multiplication so beginners would have an easier go of it. And that also included her five volume work, ''Simple Principles of Calculation,'' which were read, and influenced many scientists and mathematicians who came after her, men and women. | |||

So, remember Wang Zhenyi; mention her to your friends, perhaps when discussing fun topics like Prince Dorgon, neoconfucianism, or my favorite, the opium war. | |||

S: The opium war, huh? | |||

B: Those are all Qing dynasty things. | |||

E: Sounds like a Jeopardy category. | |||

S: So she was the Carl Sagan of eighteenth century China. | |||

B: Yeah, right? | |||

E: Sweet! | |||

S: Yeah, again, we always like to point out, think of the barriers she had to overcome. | |||

B: Oh my god! 1700's? | |||

E: At that time, forget it. | |||

B: Forget it! | |||

S: Yeah. | |||

== News Items == | == News Items == | ||

=== Restoring Hearing <small>()</small> === | === Restoring Hearing <small>(13:36)</small> === | ||

* http://news.mit.edu/2017/drug-treatment-combat-hearing-loss-0221 | * http://news.mit.edu/2017/drug-treatment-combat-hearing-loss-0221 | ||

=== Smartphone Tricorder <small>()</small> === | === Smartphone Tricorder <small>(26:57)</small> === | ||

* http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/02/18/smartphones-become-pocket-doctors-scientists-discover-camera/ | * http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/02/18/smartphones-become-pocket-doctors-scientists-discover-camera/ | ||

=== Science of Smoking Bans <small>()</small> === | === Science of Smoking Bans <small>(34:06)</small> === | ||

* http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/the-science-of-smoking-bans/ | * http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/the-science-of-smoking-bans/ | ||

=== Seven Earth-like Exoplanets <small>()</small> === | S: All right, so I'm gonna continue our recent theme about addressing empirical scientific questions that have political implications. | ||

E: Okay | |||

S: This time, we're gonna be talking about smoking bans. | |||

C: Interesting. | |||

S: And I'll tell you my bias right up front. I think that the bans on smoking in public places in the US over the last thirty years is one of the best things that's happened in my life. | |||

''(Evan laughs)'' | |||

S: Seriously. | |||

E: You don't hear me complaining! That's for sure. | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: Being able to go through my life without being subjected to other peoples' second hand smoke is wonderful. A constant irritation when I was younger, constant. | |||

E: Yes! Exactly! We all grew up in the late '60's, '70's. They were everywhere. Ash trays in every room. Smoking was still practically ubiquitous. | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: They would smoke in the mall! | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: So gross! You could smoke them ''(inaudible due to cross talk)'' | |||

B: Airplanes! | |||

C: in the '80's | |||

E: Everywhere. | |||

C: in Texas. | |||

E: Everywhere! | |||

C: Well, that's disgusting. You can't get away from that. Come on! Yeah, come on! A smoking section in an airplane when all the air's recycled? Like, who's idea was that? I've been on both sides of this, Steve, so I'm definitely interested to see this, because I know what you're talking about when you say, from your personal perspective, being able to walk down the street and not smell somebody else's cigarettes except in very specific areas is life changing. Now, when somebody's smoking outside, I'm annoyed with them. | |||

S: Yeah | |||

E: Um hmm | |||

C: But, back when I was a smoker, I remember being indignant. And I remember feeling so angry that other people were trying to step on my rights to be able to smoke wherever I want. I smoked for many, many years. | |||

E: Wow! | |||

C: And it's so funny being on both sides of that coin, because it's really difficult to see the other side. It's really | |||

S: So here's the question: What are the health effects of laws that ban smoking in certain public places. Over the last thirty years, laws have been passed. Really in the '90's is when there was a real hey day of this. In restaurants, in bars, in hospitals. Christ, when I was a | |||

C: Oh, gross! | |||

S: medical student, people would smoke, patients would smoke in the hospital. | |||

''(Cara laughs)'' | |||

S: Can you imagine that? And also, now, in universities, et cetera. Now, the thing that really pushed this over, that pushed the smoking bans over, made them politically acceptable, was data coming out in the late '80's, early '90's, showing the health risks of second-hand smoke. And recently, my updated review on this topic was prompted by an article in Slate by Jacob Greer, saying that the evidence that was used to justify these laws was overblown, and in fact, that the health risk of second hand smoke is a lot smaller than people were saying, and that maybe theses laws were not as justified as people thought. | |||

But I said, okay, let me find out for myself what the evidence actually, where are we with the evidence? So I found a 2016 Cochrane systematic review. So this is the most recent, most thorough updated review. Cochrane is pretty much the gold standard for systematic reviews. That doesn't mean I always agree with them, but generally speaking, that's a good place to start, and their conclusions are fairly robust. | |||

So this was the conclusion of this updated review: They write, <Blockquote>"Since the first version of this review was published, the current evidence provides more robust support for the previous conclusions that the introduction of a legislated smoking ban does lead to improved health outcomes, a reduction in second-hand smoke for countries and their populations. The clearest evidence is observed in reduced admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome. | |||

There is evidence of reduced mortality from smoking-related illness at a national level. There is inconsistent evidence of an impact on respiratory and perinatal health outcomes, and on smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption."</blockquote> | |||

So, that conclusion was unchanged by my further exploration. I think that's basically where the consensus of opinion is. There was another 2016 review that showed that institutional smoking bans decreased tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in those institutions, like in the university, or in a hospital, but perhaps not surprisingly, not in prisons. So the regulations didn't have any effect on tobacco use in prisons. | |||

A review in 2017, just this month, concluded that public smoking bans do not shift smoking to the home, and that smokers basically smoke less when they can't smoke at work or in public. They don't just make up for it by smoking more. And then another 2016 reviews. These, again, most updated reviews, focus on child health, found that there were benefits for children living in a smoke-free environment. So that's the most updated evidence. | |||

Now, Greer's point that if you just look at exposure to second hand smoke, and what's the increased risk of heart disease and cancer, et cetera, it is small, no doubt. And of the, this is a good historical case of widely reporting relative risk reduction rather than absolute risk reduction to make it sound a lot more impressive than it was. The absolute risk reduction is down in the one percent area, but you can make that sound like a relative risk of thirty percent, forty percent, fifty percent, so it sounds really impressive. | |||

Alternatively, if you look at it on a public health point of view, that still translates to tens of thousands of fewer people dying of smoking-related illnesses, you know what I mean? There's still a huge impact on a public health point of view. | |||

So I do think that Greer was a little selective in his reporting of the evidence in his article, and that I found the most recent, most up to date reviews were all essentially concluding the same thing, that, yep, there's a real, persistent beneficial effect here. The smoking bans are saving lives. Again, you could quibble about exactly what the number is, and the percentage is, but I think there is some benefit to them. | |||

It is also true, another point that Greer made, which is also true, is that the benefit was initially reported to be very high, and then as more data was collected, that the size, the magnitude of the benefits shrank. And he seems to think that there's something sinister about that, but just to put that in context, that is such a common phenomenon, it has a name. It's called the Decline effect. And we've spoken about this on the show before, because that's a general feature of pretty much all biomedical research, that initial effect sizes are always bigger than later effect sizes, because as you tighten up the research, and it gets more rigorous, you get better control on that positive bias that is sort of persistent throughout research. And then the effect sizes shrink. | |||

What you need to look for is, what do they shrink to? Do they shrink to zero? Or do they shrink to a persistent effect? And with the second-hand smoking literature, it seems to shrink to a persistent and real effect that, you know, the number may be small, but on a public health point of view, it's significant. | |||

Whether or not that justifies banning smoking in public places is more of a political issue, and I told you what my bias was. I think they're fantastic. But I think the data shows that there is a health benefit. And in my opinion, now this is where we get to the political end, I think that justifies a smoking ban. | |||

Also, I do think that there is an ethical way to look at this as well. This is now, we're talking more about ethical philosophy, not science or empiricism. From an ethical point of view, I do want to point out that it is a generally accepted ethical principle that negative rights, the right not to have something done to you, generally trumps or outweighs positive rights, somebody else's right to do something. So just, on that principle alone, I think someone's right not to be exposed against their will to second-hand smoke, outweighs some one else's right to smoke, especially when you're talking about a public place, or places where people don't have much of a choice to be, like school or work. | |||

This is my bias. Even if there were no health benefits for smoking bans, I still think that they're the right thing to do, just from an ethical point of view. | |||

C: Because of the nuisance, or the annoyance of the second-hand smoke. It's so hard when you're a smoker to even realise that it affects other people, because you're so unaware of it. It's one of those things where you get it cognitively, but as a smoker, when somebody else is smoking around you, you can hardly smell it, it really doesn't affect you negatively, and it's so hard not to golden rule everybody, right? When you're like, "I can't even smell it. I don't know why people think that this is so bothersome." | |||

S: Yeah, but a lot of people | |||

C: Except they can | |||

S: A lot of people, after they quit, they're like, "Oh my god! Now I know what everyone was talking about! This is like -" | |||

C: Oh yeah! | |||

B: You're nose-blind! You're really nose-blind. | |||

S: Yeah, you're nose-blind. | |||

C: It's horrible when you're in it! And you're just so self-righteous, and you have such kind of that libertarian view of, "Don't trample on my rights!" And then, once you're outside of it, you really do realise how, you know, somebody just standing on the street, which in many places is still completely legal, feels offensive, it feels like an encroachment. | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: It's very difficult. | |||

S: Also, keep this in mind: Seventy percent of smokers want to quit. | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: Right? | |||

E: Seventy percent. | |||

S: Seventy percent say, "I want to quit smoking." So, and smoking bans may help people quit. That's also, in the data, that was mixed. The results there are mixed. But | |||

C: That's interesting. | |||

S: So I'm not gonna say that that's a firm conclusion of the existing research, but there is research to suggest that it may help people in certain situations, depending on what their life situation is, it may help them to quit. But even beyond that, so essentially, you are fighting for your right to do something you don't even want to do. But you're doing it | |||

C: That's the hard thing | |||

S: because you're addicted. | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: You know, there's that addictive quality to it. And it is generally true that smokers do tend to not really understand how much of a negative impact it has on the quality of life of people around them. Like, for me, I'm particularly sensitive to it. That's just the way it is. It ruins my life! When I went out to a restaurant, if there wasn't really good separation between the smoking section, and the non-smoking section, which | |||

E: Forget it. | |||

S: basically means a different room, I was miserable the whole time. The whole thing, the experience was ruined! | |||

E: It's a pall! ''(Chuckles)'' | |||

''(Commercial at 44:57)'' | |||

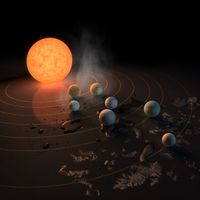

=== Seven Earth-like Exoplanets <small>(46:53)</small> === | |||

* https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/feb/22/thrilling-discovery-of-seven-earth-sized-planets-discovered-orbiting-trappist-1-star?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Gmail | * https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/feb/22/thrilling-discovery-of-seven-earth-sized-planets-discovered-orbiting-trappist-1-star?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Gmail | ||

| Line 52: | Line 230: | ||

* Answer to last week: The Big Bang | * Answer to last week: The Big Bang | ||

== What's The Word <small>()</small> == | == What's The Word <small>(58:32)</small> == | ||

* pathology | * pathology | ||

== Interview with Greg Dash <small>()</small> == | S: All right, Cara, What's the Word? | ||

C: Ooh! Okay, the word this week is a fun one. I got a tweet on February 3<sup>rd</sup> from Graham Parot, and he said, "Word of the day suggestion: Pathology. Steve uses it a lot in medical context, but I'm never sure exactly what it means." And we do use that word a lot on the show. I think I just used it earlier, when I | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: was asking about hearing loss. So, I looked at the definition from the two standard bearers, Merriam Webster, and Oxford. Generally speaking, all of the definitions are medical definitions. You can either look at it as the study of the nature diseases, included the structural and functional changes produced by diseases. And that doesn't have to be medical, right? There's plant pathology too, so more biological. | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: Or, so that's the study of the nature of disease, but also, just as a descriptor for something that is abnormal. The structure and functional deviations from the norm that constitute disease, so the pathology of something. | |||

Oxford goes a little bit further, and parses out the medical definitions. They say it's the science of the causes and effects of diseases, especially the branch of medicine that deals with the laboratory examination of samples, right? So when you think about a pathologist, they're gonna get the slides, and they're gonna maybe after an autopsy, and they're gonna look at the slide, or when somebody's alive, when something's wrong, and they'll look at the slides, and try and figure out what's going on. | |||

So they broke it down into three different things, subgroups. Medicine: Pathological features, considered collectively the typical behavior of a disease, like the pathology of Huntington's Disease is all the features collected. "Medicine: A pathological condition." Like, the dominant pathology is Multiple Sclerosis. So what is wrong with that person, or that individual? This is their pathology. | |||

And then, lastly, they say, "Usually with a modifier." So there might be mental, social, linguistic abnormality or function. So you might hear it more poetically used, like, their sentence is, "The city's inability to cope with the pathology a burgeoning underclass." So, you might hear pathology just as a descriptor of something that's wrong. It used, obviously, a lot in medicine. It is a medical term. It's used a lot in psychology. | |||

If something is - you might have heard the term, "A pathological liar," right, which is not actually a diagnosable thing. But what that means is that, everybody lies, but their lying goes beyond the norm to a pathological level. Is that a good description, Steve, based on the dictionary definitions? | |||

S: There are some nuances there, and there are people who get pedantic about the term. So, I've heard a few people chafe at using pathology to refer to the disease itself, rather than just the study of disease, | |||

C: Gotcha. | |||

S: or, like a pathological finding. It's like, "Yeah, okay. That's definition number one." But absolutely, you can use it, because it's, again, with use, it very commonly is used to refer to the disease itself. Or the finding of the disease, right? Did you find any pathology, right? So it refers to anything like that. So disease, the study of disease, the disease findings. It's often used to distinguish conditions where there is something abnormal, like on a biological level, versus something that we would consider functional. | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: Something that's functional means that the tissues are healthy, but they're just not functioning within acceptable parameters, right? So that comes up a lot in brain disorders, because the brain cells could be fine, but the function of the brain is not only determined by the health of the cells, it's also determined by the connections among the neurons. And so those connections, and the biochemistry of those neurons could be dysfunctional, even when the cells themselves are unhealthy. There may be an absence of pathology, but still, the presence of a disorder. | |||

C: Interesting | |||

S: So we often use the term to distinguish those things as well. Versus, the third category would be normal, right? Would be within the range of what | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: we see, | |||

C: Or healthier | |||

S: Or healthy | |||

C: Yeah | |||

S: individuals, yeah. | |||

C: And so, really, when you look at the root of the word, it's interesting that you mentioned that people who are a little more pedantic might say, "Oh, you can't say that that is, that one thing is pathological. You have to say pathology is a study of diseases," 'cause that's where it started. That's really, | |||

S: Yeah, sure. | |||

C: it's a science. It's the study of diseases. When you break the root down, down down down down from French, down to Latin, down to ancient Greek, you know, from pathology to pathologicia to pathos and logie, down to pathologicke, all of those break downs really come from the study of disease, right? Pathos - suffering or disease, | |||

S: Yeah | |||

C: and logia, as we know, is investigation. It's study. It's findings of that. | |||

== Interview with Greg Dash <small>(1:03:19)</small> == | |||

* Political advisor for the Labor Party, currently opposition party in the UK | * Political advisor for the Labor Party, currently opposition party in the UK | ||

== Science or Fiction <small>()</small> == | == Science or Fiction <small>()</small> == | ||

Latest revision as of 07:14, 2 June 2017

| This episode needs: transcription, proofreading, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 607 |

|---|

| February 25th 2017 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

GD: Greg Dash |

| Quote of the Week |

Science makes people reach selflessly for truth and objectivity. It teaches people to accept reality with wonder and admiration, not to mention the deep awe and joy that the natural order of things brings to the true scientist. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction[edit]

- Jay talks to his son about where the cold comes from.

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

Forgotten Superheroes of Science (11:06)[edit]

- Wang Zhenyi: Wang Zhenyi 1768-97, was a pioneer women astronomer during the Qing dynasty

S: Bob, you're gonna start us off with a Forgotten Superhero of Science.

B: Yes, for this week's Superheroes of Science, I'm goin' back a bit to the 1700's. I'll be covering Wang Zhenyi, 1768 to 1797. She was a pioneer woman astronomer in imperial China. She lived during the Qing dynasty, which is the last dynasty in imperial China. This was after the Ming dynasty, but before China became the Republic of China.

During Zhenyi's life, there was a feudal system in China, so that only allowed the rich to be educated. You had to be wealthy, but of course you also had to be a wealthy man. Women were, as usual, relegated to the tasks of sewing, cooking, taking care of the kids, and education was deemed unworthy. They were unworthy of education.

Luckily, Zhenyi's family were all scholars, and they saw no reason why she shouldn't be educated as well. And they focused specifically on astronomy and math, and she ran with it. Before too long, she was using physical models to explain how eclipses actually happened, instead of just thinking, like most people at the time, that they were just beautiful but mysterious.

She also did things like explain and simply prove how the equinoxes move, lots of stuff like that. What I love though about Zhenyi was not the new discoveries or advances, but the way she communicated to those that came after her. She seemed to take a special focus on that specific thing.

She mastered an important book at that time called Principles of Calculation by Mei Wending. And then she wrote the whole thing, but in simpler language, and made it available to others. She just took this important but kind of dense, complicated book, and rewrote the whole thing so that many more people could understand it.

She also actually simplified division and multiplication so beginners would have an easier go of it. And that also included her five volume work, Simple Principles of Calculation, which were read, and influenced many scientists and mathematicians who came after her, men and women.

So, remember Wang Zhenyi; mention her to your friends, perhaps when discussing fun topics like Prince Dorgon, neoconfucianism, or my favorite, the opium war.

S: The opium war, huh?

B: Those are all Qing dynasty things.

E: Sounds like a Jeopardy category.

S: So she was the Carl Sagan of eighteenth century China.

B: Yeah, right?

E: Sweet!

S: Yeah, again, we always like to point out, think of the barriers she had to overcome.

B: Oh my god! 1700's?

E: At that time, forget it.

B: Forget it!

S: Yeah.

News Items[edit]

Restoring Hearing (13:36)[edit]

Smartphone Tricorder (26:57)[edit]

Science of Smoking Bans (34:06)[edit]

S: All right, so I'm gonna continue our recent theme about addressing empirical scientific questions that have political implications.

E: Okay

S: This time, we're gonna be talking about smoking bans.

C: Interesting.

S: And I'll tell you my bias right up front. I think that the bans on smoking in public places in the US over the last thirty years is one of the best things that's happened in my life.

(Evan laughs)

S: Seriously.

E: You don't hear me complaining! That's for sure.

C: Yeah

S: Being able to go through my life without being subjected to other peoples' second hand smoke is wonderful. A constant irritation when I was younger, constant.

E: Yes! Exactly! We all grew up in the late '60's, '70's. They were everywhere. Ash trays in every room. Smoking was still practically ubiquitous.

S: Yeah

C: They would smoke in the mall!

S: Yeah

C: So gross! You could smoke them (inaudible due to cross talk)

B: Airplanes!

C: in the '80's

E: Everywhere.

C: in Texas.

E: Everywhere!

C: Well, that's disgusting. You can't get away from that. Come on! Yeah, come on! A smoking section in an airplane when all the air's recycled? Like, who's idea was that? I've been on both sides of this, Steve, so I'm definitely interested to see this, because I know what you're talking about when you say, from your personal perspective, being able to walk down the street and not smell somebody else's cigarettes except in very specific areas is life changing. Now, when somebody's smoking outside, I'm annoyed with them.

S: Yeah

E: Um hmm

C: But, back when I was a smoker, I remember being indignant. And I remember feeling so angry that other people were trying to step on my rights to be able to smoke wherever I want. I smoked for many, many years.

E: Wow!

C: And it's so funny being on both sides of that coin, because it's really difficult to see the other side. It's really

S: So here's the question: What are the health effects of laws that ban smoking in certain public places. Over the last thirty years, laws have been passed. Really in the '90's is when there was a real hey day of this. In restaurants, in bars, in hospitals. Christ, when I was a

C: Oh, gross!

S: medical student, people would smoke, patients would smoke in the hospital.

(Cara laughs)

S: Can you imagine that? And also, now, in universities, et cetera. Now, the thing that really pushed this over, that pushed the smoking bans over, made them politically acceptable, was data coming out in the late '80's, early '90's, showing the health risks of second-hand smoke. And recently, my updated review on this topic was prompted by an article in Slate by Jacob Greer, saying that the evidence that was used to justify these laws was overblown, and in fact, that the health risk of second hand smoke is a lot smaller than people were saying, and that maybe theses laws were not as justified as people thought.

But I said, okay, let me find out for myself what the evidence actually, where are we with the evidence? So I found a 2016 Cochrane systematic review. So this is the most recent, most thorough updated review. Cochrane is pretty much the gold standard for systematic reviews. That doesn't mean I always agree with them, but generally speaking, that's a good place to start, and their conclusions are fairly robust.

So this was the conclusion of this updated review: They write,

"Since the first version of this review was published, the current evidence provides more robust support for the previous conclusions that the introduction of a legislated smoking ban does lead to improved health outcomes, a reduction in second-hand smoke for countries and their populations. The clearest evidence is observed in reduced admissions for Acute Coronary Syndrome. There is evidence of reduced mortality from smoking-related illness at a national level. There is inconsistent evidence of an impact on respiratory and perinatal health outcomes, and on smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption."

So, that conclusion was unchanged by my further exploration. I think that's basically where the consensus of opinion is. There was another 2016 review that showed that institutional smoking bans decreased tobacco use and second-hand smoke exposure in those institutions, like in the university, or in a hospital, but perhaps not surprisingly, not in prisons. So the regulations didn't have any effect on tobacco use in prisons.

A review in 2017, just this month, concluded that public smoking bans do not shift smoking to the home, and that smokers basically smoke less when they can't smoke at work or in public. They don't just make up for it by smoking more. And then another 2016 reviews. These, again, most updated reviews, focus on child health, found that there were benefits for children living in a smoke-free environment. So that's the most updated evidence.

Now, Greer's point that if you just look at exposure to second hand smoke, and what's the increased risk of heart disease and cancer, et cetera, it is small, no doubt. And of the, this is a good historical case of widely reporting relative risk reduction rather than absolute risk reduction to make it sound a lot more impressive than it was. The absolute risk reduction is down in the one percent area, but you can make that sound like a relative risk of thirty percent, forty percent, fifty percent, so it sounds really impressive.

Alternatively, if you look at it on a public health point of view, that still translates to tens of thousands of fewer people dying of smoking-related illnesses, you know what I mean? There's still a huge impact on a public health point of view.

So I do think that Greer was a little selective in his reporting of the evidence in his article, and that I found the most recent, most up to date reviews were all essentially concluding the same thing, that, yep, there's a real, persistent beneficial effect here. The smoking bans are saving lives. Again, you could quibble about exactly what the number is, and the percentage is, but I think there is some benefit to them.

It is also true, another point that Greer made, which is also true, is that the benefit was initially reported to be very high, and then as more data was collected, that the size, the magnitude of the benefits shrank. And he seems to think that there's something sinister about that, but just to put that in context, that is such a common phenomenon, it has a name. It's called the Decline effect. And we've spoken about this on the show before, because that's a general feature of pretty much all biomedical research, that initial effect sizes are always bigger than later effect sizes, because as you tighten up the research, and it gets more rigorous, you get better control on that positive bias that is sort of persistent throughout research. And then the effect sizes shrink.

What you need to look for is, what do they shrink to? Do they shrink to zero? Or do they shrink to a persistent effect? And with the second-hand smoking literature, it seems to shrink to a persistent and real effect that, you know, the number may be small, but on a public health point of view, it's significant.

Whether or not that justifies banning smoking in public places is more of a political issue, and I told you what my bias was. I think they're fantastic. But I think the data shows that there is a health benefit. And in my opinion, now this is where we get to the political end, I think that justifies a smoking ban.

Also, I do think that there is an ethical way to look at this as well. This is now, we're talking more about ethical philosophy, not science or empiricism. From an ethical point of view, I do want to point out that it is a generally accepted ethical principle that negative rights, the right not to have something done to you, generally trumps or outweighs positive rights, somebody else's right to do something. So just, on that principle alone, I think someone's right not to be exposed against their will to second-hand smoke, outweighs some one else's right to smoke, especially when you're talking about a public place, or places where people don't have much of a choice to be, like school or work.

This is my bias. Even if there were no health benefits for smoking bans, I still think that they're the right thing to do, just from an ethical point of view.

C: Because of the nuisance, or the annoyance of the second-hand smoke. It's so hard when you're a smoker to even realise that it affects other people, because you're so unaware of it. It's one of those things where you get it cognitively, but as a smoker, when somebody else is smoking around you, you can hardly smell it, it really doesn't affect you negatively, and it's so hard not to golden rule everybody, right? When you're like, "I can't even smell it. I don't know why people think that this is so bothersome."

S: Yeah, but a lot of people

C: Except they can

S: A lot of people, after they quit, they're like, "Oh my god! Now I know what everyone was talking about! This is like -"

C: Oh yeah!

B: You're nose-blind! You're really nose-blind.

S: Yeah, you're nose-blind.

C: It's horrible when you're in it! And you're just so self-righteous, and you have such kind of that libertarian view of, "Don't trample on my rights!" And then, once you're outside of it, you really do realise how, you know, somebody just standing on the street, which in many places is still completely legal, feels offensive, it feels like an encroachment.

S: Yeah

C: It's very difficult.

S: Also, keep this in mind: Seventy percent of smokers want to quit.

C: Yeah

S: Right?

E: Seventy percent.

S: Seventy percent say, "I want to quit smoking." So, and smoking bans may help people quit. That's also, in the data, that was mixed. The results there are mixed. But

C: That's interesting.

S: So I'm not gonna say that that's a firm conclusion of the existing research, but there is research to suggest that it may help people in certain situations, depending on what their life situation is, it may help them to quit. But even beyond that, so essentially, you are fighting for your right to do something you don't even want to do. But you're doing it

C: That's the hard thing

S: because you're addicted.

C: Yeah

S: You know, there's that addictive quality to it. And it is generally true that smokers do tend to not really understand how much of a negative impact it has on the quality of life of people around them. Like, for me, I'm particularly sensitive to it. That's just the way it is. It ruins my life! When I went out to a restaurant, if there wasn't really good separation between the smoking section, and the non-smoking section, which

E: Forget it.

S: basically means a different room, I was miserable the whole time. The whole thing, the experience was ruined!

E: It's a pall! (Chuckles)

(Commercial at 44:57)

Seven Earth-like Exoplanets (46:53)[edit]

Who's That Noisy ()[edit]

- Answer to last week: The Big Bang

What's The Word (58:32)[edit]

- pathology

S: All right, Cara, What's the Word?

C: Ooh! Okay, the word this week is a fun one. I got a tweet on February 3rd from Graham Parot, and he said, "Word of the day suggestion: Pathology. Steve uses it a lot in medical context, but I'm never sure exactly what it means." And we do use that word a lot on the show. I think I just used it earlier, when I

S: Yeah

C: was asking about hearing loss. So, I looked at the definition from the two standard bearers, Merriam Webster, and Oxford. Generally speaking, all of the definitions are medical definitions. You can either look at it as the study of the nature diseases, included the structural and functional changes produced by diseases. And that doesn't have to be medical, right? There's plant pathology too, so more biological.

S: Yeah

C: Or, so that's the study of the nature of disease, but also, just as a descriptor for something that is abnormal. The structure and functional deviations from the norm that constitute disease, so the pathology of something.

Oxford goes a little bit further, and parses out the medical definitions. They say it's the science of the causes and effects of diseases, especially the branch of medicine that deals with the laboratory examination of samples, right? So when you think about a pathologist, they're gonna get the slides, and they're gonna maybe after an autopsy, and they're gonna look at the slide, or when somebody's alive, when something's wrong, and they'll look at the slides, and try and figure out what's going on.

So they broke it down into three different things, subgroups. Medicine: Pathological features, considered collectively the typical behavior of a disease, like the pathology of Huntington's Disease is all the features collected. "Medicine: A pathological condition." Like, the dominant pathology is Multiple Sclerosis. So what is wrong with that person, or that individual? This is their pathology.

And then, lastly, they say, "Usually with a modifier." So there might be mental, social, linguistic abnormality or function. So you might hear it more poetically used, like, their sentence is, "The city's inability to cope with the pathology a burgeoning underclass." So, you might hear pathology just as a descriptor of something that's wrong. It used, obviously, a lot in medicine. It is a medical term. It's used a lot in psychology.

If something is - you might have heard the term, "A pathological liar," right, which is not actually a diagnosable thing. But what that means is that, everybody lies, but their lying goes beyond the norm to a pathological level. Is that a good description, Steve, based on the dictionary definitions?

S: There are some nuances there, and there are people who get pedantic about the term. So, I've heard a few people chafe at using pathology to refer to the disease itself, rather than just the study of disease,

C: Gotcha.

S: or, like a pathological finding. It's like, "Yeah, okay. That's definition number one." But absolutely, you can use it, because it's, again, with use, it very commonly is used to refer to the disease itself. Or the finding of the disease, right? Did you find any pathology, right? So it refers to anything like that. So disease, the study of disease, the disease findings. It's often used to distinguish conditions where there is something abnormal, like on a biological level, versus something that we would consider functional.

C: Yeah

S: Something that's functional means that the tissues are healthy, but they're just not functioning within acceptable parameters, right? So that comes up a lot in brain disorders, because the brain cells could be fine, but the function of the brain is not only determined by the health of the cells, it's also determined by the connections among the neurons. And so those connections, and the biochemistry of those neurons could be dysfunctional, even when the cells themselves are unhealthy. There may be an absence of pathology, but still, the presence of a disorder.

C: Interesting

S: So we often use the term to distinguish those things as well. Versus, the third category would be normal, right? Would be within the range of what

C: Yeah

S: we see,

C: Or healthier

S: Or healthy

C: Yeah

S: individuals, yeah.

C: And so, really, when you look at the root of the word, it's interesting that you mentioned that people who are a little more pedantic might say, "Oh, you can't say that that is, that one thing is pathological. You have to say pathology is a study of diseases," 'cause that's where it started. That's really,

S: Yeah, sure.

C: it's a science. It's the study of diseases. When you break the root down, down down down down from French, down to Latin, down to ancient Greek, you know, from pathology to pathologicia to pathos and logie, down to pathologicke, all of those break downs really come from the study of disease, right? Pathos - suffering or disease,

S: Yeah

C: and logia, as we know, is investigation. It's study. It's findings of that.

Interview with Greg Dash (1:03:19)[edit]

- Political advisor for the Labor Party, currently opposition party in the UK

Science or Fiction ()[edit]

Item #1: Researchers demonstrate how they can steal data from a computer, even one that is currently air-gapped, by simply imaging the blinking light on the hard drive. Item #2: Physicists at the LHC have found for the first time an asymmetry between normal baryonic matter and its anti-matter counterpart. Item #3: A new study finds that cat ownership as a child increases the risk of developing schizophrenia by age 20 by up to 30%.http://www.cnn.com/2017/02/21/health/cat-ownership-mental-health-study/

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()[edit]

'Science makes people reach selflessly for truth and objectivity. It teaches people to accept reality with wonder and admiration, not to mention the deep awe and joy that the natural order of things brings to the true scientist.' - Lise Meitner

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References[edit]

|