SGU Episode 503

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 503 |

|---|

| February 28th 2015 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

T: Timothy Caulfield |

| Quote of the Week |

There is not a discovery in science, however revolutionary, however sparkling with insight, that does not arise out of what went before. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction[edit]

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday February 25th 2015 and this is your host Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella.

B: Hey everybody.

S: Jay Novella.

J: Hey guys.

S: And Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening, everyone.

J: What it is.

S: How is everyone doing?

J: Steve, I have bad news for you.

S: What's that?

J: I am formally out of hard drive space.

S: Is that right? Yeah... it's easy...

J: I have two four terabyte drives that Steve and I got that is housing all of our raw footage on pretty much everything we've ever done.

B: Eight terabytes?

J: Yeah, and it's formally full. Gonzo! So...

S: It goes fast, it goes fast.

J: I know.

S: I produce like 10 gigabytes a week just doing the show.

E: I tell you, we're going to see the yottabyte in our lifetime, I know it.

B: Yotta? No.

E: Yes, in our lifetime.

S: So we've been cleaning out my basement which is going to be the new skeptaliar, that's where we're going to be doing the 10 hour show in may.

B: (laughs) skeptalair.

E: Bunker.

S: Yeah. Guys, don't forget we're going to have a 10 hour live video/audio streaming event on Saturday May 2nd starting at noon so keep an eye out for that, we'll have more details coming. But that's going to be in my basement so we've been cleaning it out and I came across some floppy disks that are like literally 40 years old.

(laughter)

B: 1.44MB, baby.

E: Five and a quarter weren't they?

S: Yeah, five and a quarter floppy disks.

E: Oh, 1982.

S: And then I had the three and a half inch disks, that was the big, like these are hard-cased, smaller and higher capachity disks.

B: Those are the ones that were 1.44.

S: Yeah, now everything's on hard drive and thumb drive and solid state drives.

E: So what's on those old disks? Do you have something that you can pop in? Well they're mainly word documents of stuff that I was working on which fortunately I've sort of carried forward every time I get a new hard drive I carry everything forward from the previous iteration. But I have at times gone into those really old files and a lot of them are just almost worthless now, you can't... nothing can really read them. At best...

J: Oh, you can't open 10 year old files? I was reading about one of the guys that founded Google was saying, he says we're going to be in a huge data loss in 20 years, and that's what he was talking about, that we won't be able to have backward compatibility, won't be able to open different types of files, even a word document from 10 years ago, you can't open it on today's word.

S: Yeha, at best you get a jumble of nonsense but somewhere in the middle there is the raw text that you can pull out without formatting, that's like the best you could do.

J: But what about pictures?

S: Yeah, forget about it.

E: Wow that's a lot of data that's going to be lost.

S: Yeah, but he wants to archive it in a way, and archive the way to translate it, you know what I mean? So that we don't lose a century of data because it's not backward compatible.

E: Is that more, I suppose it's more technically complex than it sounds.

S: Probably.

J: Well really, it's saving all the different ways to decode that information, in essence it's just like an algorithm that knows how to read the different types of formats so a JPG has a specific way that it's constructed and deconstructed digitally.

S: Isn't it just a matter of just maintaining, like can't you just have one piece of software that knows how to read everything that's ever been done in the past? I mean... right? I mean how hard would it be just ot keep those, to keep the information necessary to read a word file from 1982?

J: It's not just like, oh I need to download this converter. It's more like the operating system has to be able to play with it as well, it is complicated. It's complicated enough where one of the people at Google is worried about it and is talking about it.

S: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well I threw out my floppy disks. I kept them for long enough just for sentimental value, now I just don't have room for that stuff any more.

E: Trash.

B: So Jay, 8 terabytes dude, what are you going to do about maintaining that? You know how hard drives are, I mean after a few years they are almost done, essentially.

S: Keep buying new hard drives.

B: Every two years you're just transferring it to new hard drives?

J: Yeah I've read studies about how long... I think this company, it's one of like the big cloud companies and they've been keeping very good records of the different manufacturers' brands and how long the hard drives last and like Western Digital rates very well, but still there's like a quick drop off, so they're trying to hold on to the hard drives as long as they can before they predictably are going to die. So I agree with you Bob, my long term strategy right now is I'm going to, I have online backup and I've been experimenting with different companies, I've had a couple fail me miserably but without a disaster happening, but they're charging me too much or they can't handle that size of 8TB of data. You know, what can I do, right? There's lots of things you could do. You could put it on some type of NAS storage and then just tuck it away and keep multiple copies, there's all sorts of strategies.

S: But fortunately, I mean you can get a 4TB internal hard drive for like 150 - 200 bucks, so getting a couple of hundred dollars worth of hard drives every couple of years for a business like what we do, that's not that big a deal just to make sure that we constantly have our data backed up on fresh hard drives, you know. Maybe somebody out there knows more than we do, they can make us some more suggestions.

B: I can guarantee that.

S: Yeah, probably. Alright, well we have a great interview coming up later in the show with Timothy Caulfield who, among other things, is the author of Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything?.

E: I can't wait to find out.

S: He's going to answer that question for us.

Forgotten Superheroes of Science (5:56)[edit]

- Mary Anning: Paleontologist who made significant early contributions to our understanding of prehistoric life and the history of the earth.

S: But first, Bob you're going to tell us about this week's Forgotten Superhero of Science.

B: Yeah, this one's a fun one to research. I'm going to cover this week Mary Anning who was a fossil collector and paleontologist. She discovered and prepared key fossils and influenced scientific thought about the ancient earth and extinction and paleontology itself.

S: Yeah, I read about her Bob. They called her a fossilist. I've never heard that term before.

B: Yes, very good I came across the same term and I was very impressed by it. Anning was born in 1799 and she came from a fossil hunting family which sounds like a good basis for a TV show I think.

(laughter)

E: Lost or something...

J: That is awesome. Her whole family did it, siblings as well as all of her parents?

B: Her whole family, and they did it to actually survive. Apparently the economy was bad and they actually used that money to actually eat and do stuff like that. But they sold their fossils to museums and scientists, but not only that they also sold them to European nobles who had private collections.

E: Cool.

B: Now her father died when she was young and she had to really step up this family business but she and her brother found an ichthyosaur fossil when she was 12 years old. Now this wasn't the first one found, but it was the first one that was brought to the attention of the London scientific community and it caused a sensation. And she was only 12 when this happened.

J: Wow.

B: Check this one out though. Years later she discovered the very first {{w|plesiosaur}, first one ever found, and that caused a sensation as well. And among other insights she made, she was also, she discovered the true nature of these curious objects called bezoar stones that she found or people found in the abdomen region of ichtyosaurs. She realised that these stones were fossilised excrement which were later called coprolite. So she really knew her shit apparently. So Anning, she did not have, there was no formal training. She did not have any formal training but she was described by one person as understanding more of the science of this specific science than anyone in the kingdom, she was incredibly knowledgeable and of course her father was teaching her how to do all of this stuff since she was a kid, she knew her stuff. Yet despite this, all this knowledge and all of this home training, if you will, for both the ichthyosaur and plesiosaur, Anning had, she not only discovered multiple specimens, not just one, she discovered multiple key specimens of both of these different types of creatures, but she also painstakingly cleaned them and prepared them and sometimes she even drew sketches of them that scientists used when they were discussing them with other scientists. She did it all. And unfortunately, and all too frequently, the scientists that were writing papers about what she found and doing formal presentations about what she discovered made no mention of her. They would not even mention her contribution.

J: Why, was it because she was a little kid?

E: Not a scientist, yeah?

B: No, by this point she was an adult. Well it was a combination of things. Women at that time were, just not important scientifically. I mean you were lucky if you were even literate, let along acting like a scientist.

S: And when they were, when they were interested in science, there was like acceptable avenues. It was acceptable for women to be specimen collectors but not do anything too "thinky". You know what I mean? They couldn't to actual science, but if they wanted to go out and collect stuff, then the men could describe and get the credit for it, that was fine.

B: Yeah. I mean later no in her career people definitely were giving her more respect and they were saying, hey by the way this was found by Mary Anning and she did get some of the credit but there were lots and lots of instances, I counted six, where they just did not even mention her to the people who were presenting what she had found, and not just found, like I said, she completely cleaned it, prepared it, did all that stuff. So her discoveries, though, this is very important, her discoveries came at a time when many scientifically adept people at that time period did not believe in basic things like extinction or the vast age of the earth. So the fossils at that time, the early fossils, a lot of them, they were unusual, they were things like mammoths so people would often just say, oh, you know, these creatures still exist, they just exist somewhere that's unexplored and we just haven't found them yet. But her discoveries and those of other people showed the scientists that animals this foreign really did exist, they existed long ago and they are not alive now, and that was a very important thing. But not only extinction though, she also helped show that an ancient Earth was possible. Earth was not 6000 years old as many people believed. As you can imagine, in the early 1800s, the vast majority of people believed that the earth was 6000 years old. She helped force the realisation that the age of reptiles was real and it actually entered peoples' conciousness that yes, these animals lived and dominated the planet for many millions of years and they ruled over mammals. Mammals were just not important at all at that time. And then another thing that came as a surprise. She was a key early player in geohistorical analysis, using fossils to reconstruct extinct organisms and environments which later became, of course, palaeontology. She was a key player in the rise of palaeontology itself, which I found incredibly impressive. So, read up on Mary Anning, mention her to your friends, perhaps when discussing ocular cavities in basal ichthyopterygia. She needs to be remembered.

S: Bob, are you aware that a new ichthyosaur has been named? Ichthyosaurus anningae, after Mary Anning.

E: Oh, cool.

S: Just recently.

B: Yes, I was, and it's really good because earlier in her career, after she was well established, people did notice that it was really kind of ridiculous that people that she gave fossils to had these creatures named after them, but not her. But then...

J: Oh, she's goign to be psyched to hear that!

(laughter)

B: Yeah right, yeah right. But there are a lot now Steve, there are a lot now Steve.

S: So it's interesting, this ichtheosaur...

B: There are a lot that have been named in her honour at this point.

S: Yeah, yeah. Well she deserves this one because it's an ichtheosaur.

B: Absolutely.

S: But this ichtheosaur was sitting in a museum drawer and was rediscovered in 2008 by another self-taught palaeontologist Dean Lomax. Dean Lomax noticed that there are some differences, this one has some anatomical distinctions that are different from any other ichtheosaur. So he was able to identify it as a new species and named it after Mary Anning which is very, very nice.

B: Awesome.

S: Ichtheosaurs are a very interesting group, I wrote about them in our science news page so take a look at that if you're interested.

News Items[edit]

Marijuana Safety (13:04)[edit]

S: Alright, let's go on to some news items. Jay, there's a new scientific report about the safety of marijuana.

J: In the United States guys, as you know, cannabis marijuana, weed, whatever you like to call it, it has been thought to be a very dangerous, and arguably became the most fought against drug, right? We had the whole reefer madness thing going on.

E: The war on drugs.

J: The war on drugs, exactly. Over the past 20 years though, a lot of opinion has changed, significantly in fact, to the point where a lot of states in the United States are now legalising marijuana and even releasing some people that are in prison that have certain levels of convictions, right?

B: Alaska recently legalised it.

E: Very recently, yeah.

J: A recent study tested how deadly are several common and popular drugs, and it did a side-by-side comparison with some very interesting results. The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports which is a subsidiary of Nature. Steve, I'm sure you've heard of that one.

S: Mmhmm.

J: The drugs they tested were cocaine, jack(?) tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, ecstasy, meth and heroin. Guys, take a guess, which drug was the most deadly? Evan, please start.

E: Well I start about that before I actually saw it and I would have guessed meth would have been probably near the top if not the top, but it turns out I'm wrong.

J: Bob?

B: Tobacco.

J: Steve?

S: No, I mean any physician knows alcohol's an extremely toxic drug, it wrecks people.

J: So in order of the most deadly, guys you guessed well. Alcohol, then heroin, then cocaine, Jack tobacco, ecstasy, meth and cannabis at the very end of the list. Now the amazing finding was that cannabis was far and away not even near the other drugs. In fact they found that cannabis is 114 times less deadly than alcohol. Now that's, I know that it just sounds like a number, but when you see the chart and alcohol is in the deadly slice which is all the way to the left, cannabis is all the way to the right, which is very profoundly not that deadly.

E: In those statistics, for example, is it considered for people behind, driving under the influence of alcohol dying in crashes versus people under the influence of marijuana dying in crashes, is that like a fair kind of comparison that's taken into consideration?

S: No.

J: I don't think they went there, no. I think they were just studying its biological effects.

E: OK so it's how it directly affects the human body.

B: Jay, so are you saying that cannabis is the gravity of drugs?

J: Yes, it is the weakest of the drugs tested, Bob, very good.

B: By far, very good Jay, you got that, you've been listening.

J: I've been listening to you in particular, and Bob, you're my hero.

B: (laughs)

J: You're somebody's hero. Steve, a few weeks ago you mentioned what was it, the DL50 test?

S: LD50.

J: The LD50 test, and they were using that methodology, or they were using that for the scale to see which drugs were the most deadly.

S: They also, they were using another measure too, not just the LD50. BMDL10 which is the dose which gives you a 10 percent increase in the risk of dying. The authors are careful to point out that the only thing they're comparing here is the relationship between the dose typically used and the dose that'll kill you.

J: Right.

S: That's what they're looking at, they're not looking at all of the effects of the drug, and even in the discussion, the authors say, this does not mean that regularly using heroin doesn't have horrible health effects. It just means that the typical dose that's used in relationship to the dose that's likely to be fatal. And that's where cannabis is very safe from that point of view because it doesn't cause a lot of acute toxicity, but that doesn't mean that, it doesn't say anything about the long-term effects of chronic exposure, they're not really looking at chronic exposure, just...

J: Right, which can have a lot of profound effects.

E: Liver failure.

J: Right, or cannabis could have emotional and psychological effects as well or whatever. So cannabis was the only drug out of the lot that had a low mortality risk. All the others had a relatively high or high mortality risk. Surprisingly, ecstasy and meth were the second and third least deadly. Keep in mind that they were very far away from cannabis but still they were a lot less deadly than alcohol and tobacco. Alcohol is so bad guys, it's more dangerous than heroin. It's really, really, really bad.

S: Well when you think about it, people drink toxic amounts of alcohol. When you're drunk, right? You're essentially...

E: Poisoned, technically.

S: If you think of alcohol as a drug, you're overdosing on alcohol deliberately in order to get the toxic effects so people actually push alcohol to toxicity as part of recreational use. Does that make sense? So it's actually not that far from there to dying of alcohol poisoning.

J: It's important to state guys, again like Steve said, this isn't an invitation to go buy a bag of weed and smoke yourself into Spicoli (?) Land. There's a growing mindset that since marijuana is natural, that it's safe. And the word natural is almost meaningless when we talk about safety. That would be like me saying that naturally occurring chemicals are safe or safer than non-naturally occurring chemicals, and that's bullshit.

Phantom Acupuncture (18:30)[edit]

S: OK let's move on. Have you guys heard of phantom acupuncture?

B: Yes, I have.

E: Is that a new play Andrew Lloyd Webber? That guy.

S: So, this is... I've heard of placebo acupuncture and sham acupuncture, now we have phantom acupuncture. So listen to this, this is what some researchers did.

E: OK, sounds redundant but alright.

S: Right? Well I think that was the point. You know that we can induce the experience of a phantom limb in a laboratory with pretty good reliability now.

B: Yeah, it's pretty cool.

E: It's remarkable.

S: The procedure is actually pretty simple. Let's say you're sitting in front of a table and one of your arms is on top of the table, the other one is under the table, and they're both sort of covered with a blanket and then there's a manikin or rubber arm on top of the table over your arm that's under the table. Right, you get that?

B: Yep.

S: So it looks like you have two arms on the table but one is rubber with your real arm being hidden under the table. And then, while you're looking at your arms, if somebody strokes the rubber arm in the same place and time that they stroke your real arm, you will feel and see the rubber arm being stroked. That's how your brain determines that you own the different parts of your body, right?

E: Steve, the brain overcomes the actual, I'm not sure what to call it, illusion that the rubber arm is made of rubber? It's able to sort of look past that?

S: The question has some assumptions in it that I think I need to address. Let me back up and just explain how the brain generates the sense of ownership in the first place. It's an active process and essentially what it's doing is comparing multiple different sensory streams at once: what you see, what you feel, what your motor planning is doing. Are the parts of your body doing what you want them to do? And then there are circuits that are comparing that information and they create the subjective sensation that we own the parts of our body and that we control the different parts of our body. There's actually a module in the brain called the ownership module that gives you the feedback that you own a part of your body. What happens in a phantom limb is that the ownership module still exists but even if you've had a limb amputated or it's dead, and so it's creating the sensation that you own this limb even if it's not there. And I know we've talked on the show about super-numinary phantom limbs where people have had, like after a stroke and part of their body is paralysed but their ownership module is still functioning, the ownership module may create a phantom limb because it's being deprived of the normal feed back that it gets, and so people have this hallucinatory limb, they think they have this extra arm that they feel like they own and can control.

J: Now Steve, also when someone loses a limb they could have phantom pain which is an odd phenomenon as well.

S: Right. One wrinkle to that is, like some people, their phantom sensation, like so they've had their arm amputated. They might feel like their fist is clenched and they're digging their fingernails into the palm of their hand and it's painful. One of the treatments for that is to put a mirror up so that they're looking at their intact limb but their brain sees it as their missing limb and then they open their hand so it's like visually signalling the brain that they're opening the phantom limb. And that often works. It takes the pain away.

B: Silly brain.

S: Yeah. So anyway, so now we'll get back to the acupuncture. If you do this with somebody and they successfully own the rubber hand, because of the tactile illusion, then they give acupuncture to the rubber arm. Right, so that's phantom acupuncture.

B: Wow.

S: What they found is that the brain...

E: The brain lights up.

S: The brain lights up in an fMRI scan, it responds in a way similar way to acupuncture of an actual limb.

J: Whoa.

E: Whaaaa...

S: When doing acupuncture of a phantom limb.

E: Oh my gosh, isn't that kind of a case closed kind of scenario. That's it?

S: Yeah.

B: Steve, are you saying that the rubber arms actually have meridians inside?

S: Yes, so obviously...

(laughter)

E: That's exactly what he's saying.

J: Yeah Bob, if you have a AAA battery in it, yes.

S: Yeah, it's beyond absurd to think that there's chi and meridians, life force, flowing through this rubber arm but it emphasises the fact that, how subjective these sensations are, and that even just visually tricking the brain is enough to get it to respond in a way that it thinks that it should be responding, it's sort of generating the expected experience even when nothing is actually physically happening, in this case, this is a pretty darn good control. The acupuncture is happening to a rubber arm so it can't be doing anything physiologically. The only real thing that's happening is that you're seeing it happen to an arm that your brain has been tricked into thinking is part of you. So yeah, isn't that fascinating? Now I always have to throw in the normal caveats here, this is one study, fMRI studies are really tricky to do, it would be interesting to see this replicated and to see how far we can take this but yeah, I found this very interesting. Now of course, some people will say, OK well acupuncture works by tricking the brain into thinking you're not having pain. So what? You're still not having pain. But that still gets you back to it's just an elaborate placebo, do you know what I mean? It doesn't mean you can treat cancer with acupuncture, that's always the problem I have is that they're using how easily our perception can be manipulated to say that there is something specific about acupuncture that has a specific effect and that the underlying philosophy is correct and all of that stuff and therefore I'm going to use it to treat high blood pressure and cancer and mumps and all of this other nonsense. But meanwhile studies show that just pain is incredibly distractable. You know, if you just look at the other arm while a procedure is being done on one of your arms, your perception of pain will be less, for example.

E: I do that when I get a shot in the arm, I turn away and concentrate on some other part of my body or something and I don't feel it.

S: Yeah exactly. Whereas if your attention were focussed on it it might be incredibly painful, but this pretty much undercuts the notion that therefore it must have a specific physiological effect or that chi is real or meridians are real, there's no support for that in any evidence.

E: So what's left? I mean the whole acupuncture paradigm falls entirely apart as far as I'm concerned.

J: Oh it won't do anything. Evan, nothing is going to change.

E: Oh I understand that, it's not going to convince the true believers, but that part of their argument is now entirely gone. It's over.

S: Yeah. So this wasn't looking at a clinical response, this was just looking at the brain response on an fMRI scan. The researchers said that they want to do follow up studies looking to see if there's a clinical response and that will be interesting as well. Other research already has shown that the only thing that really matters to the effect of acupuncture right, it doesn't matter where you stick the needles, it doesn't matter if you stick the needles, it doesn't matter if it's a trained acupuncturist or somebody who was just told ten minutes ago how to fake their way through it, none of that matters. The only thing that matters is the interaction between the acupuncturist and the patient. And the more supportive they are, the more positive they are, the better the outcome, and that's it. You could be randomly poking them with toothpicks but if you're nice and positive and confident they'll have a placebo effect. That's it.

E: What's next, virtual acupuncture in which you don't even have to touch the patient?

S: Well you don't, right? Therapeutic touch is virtual acupuncture, basically. Just waving your hands over somebody, literally there's nothing physical happening.

E: But they didn't call it something cool like virtual acupuncture.

S: There you go Evan, that's going to be your pseudoscience, you could do that, make a million bucks.

E: Alright! I'm getting the t-shirts made now.

S: Virtual acupuncture.

B: I'd go for multi-dimensional acupuncture.

S: Guys, quantum acupuncture.

B: Oh, there you go.

E: Oh, gosh.

J: That's good.

E: Wait, Deepak might already own the rights to that, we're going to have to check on that, yeah.

S: Yeah, that one's probably out there already.

Liberal and Conservative Biases (26:54)[edit]

S: All right, Evan, I understand that both liberals and conservatives can be anti-science.

E: What? Are you kidding, Steve? Have you read Facebook lately?

S: Unfortunately, I do.

E: And an Ohio State University study, which appears, or is going to appear in the annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science in their March 2015 issue, is going to make that very point, that liberals, as well as conservatives can be biased against science that doesn't align with their political views.

The study found people from both the left end of the political spectrum and the right end of the political spectrum expressed less trust in science when they were presented with facts that challenged specific politicized issues. Now, can you guess what the top two bugaboos for conservatives were?

S: But these are the ones that were chosen by the researchers. They weren't necessarily ones that were determined to be the big issues for Republicans.

E: It's a good point, Steve, yes.

S: Because, and I make that point because the ones that were chosen by researchers for the liberal side were nuclear power

E: and fracking.

S: and fracking. Fracking's actually not a bad one. But, they found an asymmetry. They did find an asymmetry, meaning that the two sides didn't respond exactly the same. Republicans were about four times more bothered by being contradicted in their beliefs than the liberals were, which is similar to the kind of stuff that Chris Mooney says, right? That the Republicans, they're more anti-science because of their basic ideology. But

E: Right

S: I have the same problem with this study that I had with the studies that he did. And that is, there's an inherent asymmetry in the topics themselves, and the authors here acknowledge that. They say that, "Well, maybe it's just that global warming is a much hotter topic than nuclear power is." And so that's why they get more upset. So I keep wanting someone to do this study with something like GMO. And

E: Right

S: I predict, even though that's not as cleanly left / right, 'cause it's the anti-government people also don't like GMO. But in any case, if the liberal anti-GMO faction, I bet you, they would be as similar type of response as the anti AGW right side of the spectrum.

E: Another problem that, as long as we're on to the problems already about this particular study. It's very revealing, very interesting, but it's a little too simplistic.

S: Yeah

E: I mean, there's two groups, right? Are you conservative or are you liberal? Well, that doesn't, that's not a one size fits all, or, it's not a real choice. I mean, there are lots of different issues.

S: The conservatives were really religious right. They really should have used religious right, you know,

E: Yeah

S: 'cause you're right. 'Cause like, a libertarian would have had a completely different response, I think.

E: Right, absolutely. And some people are conservative about some things, and quite liberal about other things.

J: Right

E: It doesn't identify their, how they think about all issues. So it's much more gray scale than they afforded here. You know, they really just use black and white, basically. So that was kind of another problem I sort of had with this. But it does go to show, and I think it's been our experience for the ten years we've been doin' the podcast, and almost twenty years that we've been involved in the skeptical movement, is that there is - political affiliation does not necessarily make you either more knowledgeable about science, or have a better appreciation of science than not.

And people who are, you know, on whatever side of the political spectrum you want to place yourself on, just as susceptible to all of the human frailties that are, that we know

S: Yeah

E: exist. Anybody can be biased.

S: I think was the scientific literature shows, that this is tapping into some basic human psychology. You know, motivated reasoning, defending our positions, the role of ego, et cetera. All these psychological studies show that there are basic psychological biases that would lead people to stick to their guns in the face of scientific evidence. And the interaction with their political views is interesting.

I'm not totally opposed to the idea that there's a difference between people who are ideologically conservative and ideologically liberal. I'm just not convinced by the current evidence, because of this issue that these researchers bring up, that the issues themselves are inherently unbalanced, and, so I need to see, and they use the same topics. They used the same exact

E: Yeah

S: challenges that Chris Mooney did in his research, which is interesting. I mean, I want, why hasn't anybody done this with GMO's, for example? Or just try to pick issues that are gonna be as emotional, as politically controversial, in the current environment. And

E: Sure

S: to see if it really is the ideology of the people, or just the intensity of the issues that's driving the difference in intensity between the two sides here. I would just be

E: Sure, sure! Let's see how vaccinations charts

S: Yep

E: in this area. That's another example.

S: Although the anti-vaxxers, again, are kind of, they bridge right and left. They're not strictly liberal.

E: But the researchers in this study, Steve, chose these, I think they chose polarizing topics,

S: Yeah

E: which are obviously polarizing to make their point. But here was an interesting little tidbit as well, that I pulled from it, is that the issues themselves make both sides lose some trust in science.

S: Yeah, that's true.

E: And one of the researchers said that even liberals showed lower trust in science when they read about climate change and evolution, which are issues which they normally, which they agree with in the

S: Yeah

E: scientific community. But just reading about the topics, they're so polarized, has a negative effect on how people feel about science. And I think the media has a lot to do with that.

S: Yeah, I agree. And we've talked about other studies which show the same thing, that any polarization or controversy tends to lower confidence in the science itself. And that's why

E: Yep

S: you probably should just turn off comments on certain science news sites.

(Evan laughs)

S: You know.

E: Oh yes.

S: 'Cause it's just, the negative comments, or controversial comments have an overall negative effect. It's just, I think, one of the things that we're learning as we adapt to the new social media that we're dealing with.

E: Well, there you have it.

S: There you have it.

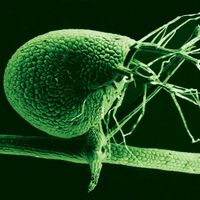

Bladderwort Genome (33:23)[edit]

Who's That Noisy (37:42)[edit]

- Answer to last week: Shepard's Tone

Dumbest Thing of the Week (41:00)[edit]

S: Alright well, we have another installer of the Dumbest Thing I Heard This Week which I guess is going to be the working title for a while.

J: Steve, can I bring up things that I hear at work?

S: It needs to be something in the public domain I think. It is remarkably easy to come up with bits for this segment, I mean it like writes itself. This week we have David Tredinnick who is a conservative member of parliament in the UK, and Tredinnick says he has the solution to the rising health care costs in the National Health Service in the UK, and that is: astrology.

(laughter)

E: Oh he's got quite a sense of humour, he's a regular Stephen Fry.

S: Yeah (laughs). He says, "I do believe that astrology and complementary medicine would help take the huge pressure off doctors."

E: Oh he's serious?

S: He's serious. He thinks that, "Astrology offers self-understanding to people. People who oppose what I say are usually bullies who have never studied astrology." So he's playing the you don't know the research card. He thinks astrology could be a diagnostic tool.

J: Really? OK, well what's his mechanism?

S: Jay, don't get in to mechanism, come on. What, are you crazy?

J: I'm just asking questions, Steve.

E: This guy is in parliament, and you're nothing. Don't...

S: Criticizes the BBC for being dismissive of astrology. Yah! Dismissive of nonsense.

E: That's right, he took down Professor Brian Cox too, for his dismissive approach, yeah.

S: Yeah, criticized Brian Cox, yeah.

E: Racially prejudiced?

S: Yeah, if you are opposed to astrology, you're racially prejudiced. Racially prejudiced, yes.

B: No, you're stupid prejudiced.

S: Tell us, tell us, Mr. Tredinnick, what's the race that promotes astrology or that culturally came up with astrology, tell us please, what race we're being prejudiced against when we say that astrology is complete and utter hokum?

E: I think he'll say, "the human race."

J: Yeah, I'm serious. I'm not sure he knows what the word really means, I think he thinks it means something else in that context.

S: Yeah, it's hard to know.

E: Guys, this guy won an election. I mean swaths of people turned out and pulled a lever for this guy.

S: So in any case...

B: His lever was certainly pulled.

S: Skeptics have looked at the data for astrology. First of all, it's, as Jay said, there's no possible mechanism. The idea that the apparent position of stars relative to each other or to the planets at the moment of your birth has some influence on you is pre-scientific superstition. Seriously, it's so old-school, like we don't even bother talking about it any more. I remember the first skeptics conference I went to they had a breakout session on astrology, there were three people in there. No one cares. You know what I mean? It's so played out, the idea that it's cropping up again at this level, a member of parliament. Astrology? Really? I mean that's just, that's embarrassing.

J: That's what you're going to tie your horse to? Like, that one? Alright, OK, here we go, break out the 50 year old literature.

S: (laughs) Right.

E: All praise Zeus I guess.

S: You haven't read the research... no, it's that we read it 50 years ago. So that's why David Tredinnick earns the Dumbest Thing I Heard This Week.

E: Well he earned it, the old fashioned way.

S: (laughs) I don't know how many people are going to get that Joke, Evan.

E: (laughs) It's a bit dated.

S: It is a bit dated.

Interview with Timothy Caulfield (46:13)[edit]

S: Joining us now is Timothy Caulfield, Tim, welcome to the Skeptics' Guide.

T: Hi There.

S: Tim, you're the author of two books, at least two books: Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything? When Celebrity Culture and Science Clash and your previous book The Cure for Everything, Untangling the Twisted Messages About Health, Fitness and Happiness. Are those your only two or do you have any other books?

T: I've got some boring legal ones that are probably less interesting. For the general public, those are the only two.

S: OK, great. Tell us a little bit about yourself.

T: I'm a health policy researcher here at the University of Alberta, and I like to think that we do very inter-disciplinary work looking at science policy, health policy issues ranging from really everything from stem cell research to obesity policy to complementary and alternative medicine, and what we really try to do is look at what the best evidence says about a given topic and then apply that to the policy issue, and that's what really brought me into the two books that you just mentioned, I've become increasingly interested, really over the last decade, in what the science says about particular health policy issues. And as you know there's often a massive disconnect so that's really what brought me into this.

S: Can I ask you, do you tend to take an evidence based approach or a science based approach?

T: You know what, that's a great question, it's something that I've been grappling with over the last couple of weeks, now I always think that I take a science based approach, but I've been accused of taking an evidence based approach because people love to draw on literature that talks about problems with evidence based medicine. But I really think of myself as a science based scholar.

S: Yeah. So you'll consider the plausibility of the treatments that you're evaluating.

T: Yeah, that's right, that's right.

S: So tell us, answer the question in the title of your book. So is Gwyneth Paltrow wrong about everything?

T: Look, she's... she's got great style and I think that she's a fine actress and when I was younger I think I may have even had a crush on her. But she's wrong about an awful lot and the reason that I... if you've read the book you'll know that I don't really pick on Gwyneth that much, I talk about a lot of other celebrities but I just think she's such a great example of the place of celebrities in our lives right now particularly in the context of science and health and how we think of the good life because not only does she talk about these things all the time, right? Whenever she gets the opportunity. She also, it's part of her brand, right? So it's part of how she markets herself to the universe so that's why I picked Gwyneth for the title and that's why I start the book with a little bit of some Gwyneth stories.

S: Yeah, so was the book in time to catch the whole steaming her vagina?

T: I know, no I missed the v-steam. But you know it was happening right when I was doing my book tour so I mean, thank you Gwyneth, I think I owe you a cheque or something. I mean you can't make that stuff up, right? The vagina steam. It's funny, I was talking about it in class earlier.

J: Hey, does she know about the book?

T: It's a great question, as you can imagine I get it all the time. I haven't heard from her yet, I reached out to her, I reach out to her on twitter all the time and of course I've tried to reach out to her people. When I was writing the book I got close to her, in the sense that I talked to many people that were close to her and they always said, oh Gwyneth would love this, I'm sure she'd love to talk to you and it never went anywhere. As you know the book hasn't been released in the U.S. yet so it'll be interesting to hear what happens when it comes out there. I'd love to talk with her, I always joke that I'd love to sit down and have a green tea with her and tell her about all the things that she gets wrong. (laughs)

S: How do you think she would respond, do you have any basis for an opinion on that, have you had a confrontation with any other celebrities about their nonsense?

T: I think that's a fascinating question, it's one I'd actually like to study believe it or not because I'm sure you guys think about this too: does she really believe the stuff that she's saying? And in fact I've always thought that if I had the chance to talk to Gwyneth, to interview her, I'd probably only get one or two questions. I'd probably be in a scrum. And the one question I was going to as was, Gwyneth, do you really believe the stuff that you say? Because I don't know, I don't know. I wonder that about other quacks, I wonder that about people who sell unproven stem cell therapies, I wonder that about homoeopaths. Do they really believe it? And I think there's probably a continuum out there and I suspect that Gwyneth falls on the side of the continuum where belief is real.

E: Yeah Tim, I agree with that, and here's my reasoning why. It's because this is not, primarily at least, what she does or what she's known for. She's an actress, she's a singer, she's this amazing super-star, people magazine every other week. She didn't really need to go ahead and do this and her whole Goop website which ties all these things together, it wasn't out of any sort of necessity so what other motivation would there be if she really didn't believe in these things?

T: Yeah you're absolutely right, and it's not like she has training in this and that it's part of her self-identification so she's got to stick with it, right? A personal philosophy. And also I note in the book, I don't really blame celebrities for their position because, look Gwyneth and all, particularly women, but really all celebrities are under incredible pressure to look good, to look young, and so I think they are victims probably more than anybody right? They've got to do whatever they can to stay youthful looking. So I wonder if that's part of the process that allows them to try a whole bunch of crazy things and then it's a slippery slope, they start telling the world about it and then before they know it they've got a clothing line and a cleanse product. So yeah I think that you're probably right.

S: Yeah and of course the audience here is not the celebrity, I mean I don't think there's a reasonable chance you're going to convert Gwyneth Paltrow to skepticism but we're trying to use her as a jumping off point to educate the public about the scientific process, health claims etc. But can we really have a significant impact compared to the power of celebrity?

T: You know, one of the things that I wanted to do with this book is, it's a little bit of a Trojan Horse, right? I know that there is this incredible fascination with celebrity and celebrity culture, in fact, you guys are probably aware of some of the speculation in scientific literature that we may be evolutionarily predisposed to follow celebrities and as Edward L Wilson talks about our love of gossip and of hearing about other people. So I think that's one of the reasons that I wanted to write the book, because I thought it was an excuse, a Trojan Horse to really bring in this discussion about science. Are we ever going to be able to combat the power of celebrity through skepticism and teaching science? I think probably not, but I do think, and one of the things that I recommend when I speak on this, I do think that the scientific community has to get more involved with popular culture and I think that (inaudible) and even over my career I've seen a massive difference, people used to look down on you if you were in popular culture, if you had a blog or if you tweeted. I don't think, I think that's changed. I think that people understand that scientists need to be a part of the discussion because if there isn't that voice out there it's just going to be Katy Perry and Gwyneth, right? So I don't think we can ever completely compete with it but I think we have to be part of the discussion.

S: Yeah I agree with you, I think that the scientific and academic community needs to be much more involved with popular culture than they are right now and while things have improved, academia is still a mixed bag in terms of how they view academics who engage with the popular culture. We're not there yet, let me put it that way.

T: I don't think we're there yet either. I think you're right. I mean people, they assume if you've read... it's the Carl Sagan effect right? The guy was doing great science his whole life and I think that his... you often hear how people viewed him differently as a result of the work that he did, and I think that's a shame. I think that you can do both and more people should. And the other thing that scientists should do and I think are doing increasingly is when they hear something inaccurate, speak up, right? And I think that is something tangible that can be done. I'm fortunate, I serve on a lot of scientific committees and that's a recommendation that often comes out, in the context of stem cells for example. When scientists hear something inaccurate stated about, you know, whether Gordie Howe getting a stem cell treatment, that they should speak up and get on the record about what the state of the science really is. And I think I'm seeing that more and more, do you agree?

S: I'm seeing everything more and more, just because of the internet.

(laughter)

S: We're still, I think, drowned out by orders of magnitude in terms of just the amount of information that's out there. Despite that we can have a hugely disproportionate impact. So how much are you involved with regulation of health care in Canada?

T: Well I have been involved in, (inaudible) I would say, in a variety of capacities have been very involved, I mentioned stem cells a couple of times, I've been involved in stem cell policy here quite a bit, in genetics, served on a variety of advisory committees. And so that's where, throughout my career I've seen people trying to integrate science into policy-making, and it's tough sometimes, because you've got to balance public desire, public perception, political issues, with what the science really says and sometimes the best response doesn't always emerge but at least you have to have science at the table.

S: Did you follow the cases of the, the two recent cases of the little girls, both native like six nation girls who had leukaemia and were going to a Florida clinic to receive traditional care and that became a court case over whether or not the state could require that they take chemotherapy?

T: Yes, I followed that quite closely and as a law professor it's a fascinating case and obviously I was very disappointed with the results and it's a wonderful example of how politics and law and cultural sensitivity can complicate, I'm trying to think of the right terms, choosing my terms carefully here, can really complicate a decision that would really hope would be driven by the best interests of the child and by science, and what's fascinating about that case, and I don't want to get too much into the law, is that there really was, there really is some complicating constitutional law that was used to justify that decision. I think everyone in my community is disappointed by the results and unfortunately now we have that precedent so it'll be interesting what happens when future cases emerge.

S: So was that really just up to the judge or, did they have discretion to go either way, or do you think the laws as they're written, this is the only way that the case could have gone?

T: So I think it was, I think it was wrong legally. I don't think that they interpreted the constitution the way that it could have been interpreted. Having said that, there was more nuance to the law than perhaps is often portrayed in the popular press describing the case. I think, where I think the judge got it wrong was claiming that this was a cultural practice that therefore exempted it from Canadian law. I don't think, I think the best interests of the child should have prevailed, which has in the past in Canada, in other cases. The classic example is the Jehovah's Witness cases, and there's cases in the US too that are like that. So I was, again, I was disappointed, particularly since, in this case, the science, the clinical evidence was so clear, right? It wasn't a situation where people were arguing to any great degree about the actual science, but it was really about the cultural practice. So again, a disappointing decision.

S: Yeah I agree, you're right, this is one of the most clear cases you can possibly have. Almost guaranteed, like 85% cure with standard therapy and almost guaranteed that she will die of her disease without standard therapy so there was no scientific, really, debate here. I also found it very interesting, and I don't know how much this came up in the case or the press in your neck of the woods, that the "traditional" healing that was being sought in both cases is some white guy in Florida peddling snake oil that has nothing to do with six nations traditional healing practices.

T: Yeah, for sure that came up, right? For sure that came up. And I found that infuriating, and I think, was it just today or yesterday that he had his license pulled? Or yeah, I don't know if I'd call it a license that was pulled.

S: He doesn't have a license. The state told him to stop practising medicine without a license.

T: Yeah exactly.

E: They gave him one so they could pull it.

(laughter)

T: There was nothing to pull. Yeah I found that really frustrating. But you know, that happens all the time, right? In complementary and alternative medicine, that homoeopathy is portrayed somehow as having this great cultural depth to it or something when it was invented (inaudible) right? And so I find that very frustrating and that was certainly the situation in this case. Just because it's an alternative practice does not mean that it necessarily has some great cultural history to it that exempts it from scientific scrutiny.

S: And of course, even if it were cultural, I think at the end of the day, society has a responsibility to a child, and they utterly failed both of those girls. One is now dead. The other one probably will be soon, which is unfortunate, that's the bottom line. No matter what you think the child is dead. So the story is over for her.

T: It is. It's just incredibly heartbreaking and one of the things that's so frustrating as a law professor is that we had this string of cases that I think clearly gave the court jurisdiction to step in, this was really about cultural practice and that's what it came down to, and I'm sure you've heard this, there was discussion amongst the media that people shouldn't be speaking so harshly of the native community in this regard, there really was, it was a vicious kind of debate and the end result was just tragic.

S: Alright well Tim do you have anything in the future that you're working on that you'd like us to talk about?

T: Well we are looking at things like supplements, we just finished an interesting paper on vitamin D which is another discussion we could have, that's like a religion and we were looking at how vitamin D was represented in the popular press as compared with what the actual scientific literature said on it. And we're looking at a couple of other things. The other thing that we're doing right now is looking at how science is represented on twitter. We're looking at it in the context of things like stem cells and we're using the Gordie Howe incident as an example. And the other thing that we have, we have a paper coming out in Science Translational Medicine next month where we look at claims about how soon stem cell research is going to get to the clinic and so, time to the clinic. And it's always 5 years in the future, right? That it's going to be in the clinic. So we think that's a really good example of science hype and how that can feed the science-sploitation phenomenon that I talked about. Because I do think that scientists take a little bit of the blame for some of the phenomenon that we're talking about in the context of science-sploitation because there's just been so much hype on that. So that's some of the work that we're doing right now and I've got a great interdisciplinary team, I like to believe that I just sit on peoples' coat tails and have fun.

S: Alright, Tim well it was great talking with you, thanks for being on the show.

T: A real pleasure guys, thanks so much for all the great work that you guys do.

S: Well, thank you.

J: Thanks, Tim.

E: Thanks, Tim.

Science or Fiction (1:02:46)[edit]

Item #1: In Stockholm, wild rabbits are being culled and their corpses are being burned in a heating plant in central Sweden. Item #2: A Beverly Hills plastic surgeon used the waste from his patient’s liposuction to create biodiesel to fuel his SUV. Item #3: On the International Space Station, human waste is dried to reclaim moister, and the remains are burned to produce power for the station.

Skeptical Quote of the Week (1:12:19)[edit]

'There is not a discovery in science, however revolutionary, however sparkling with insight, that does not arise out of what went before.' - Isaac Asimov

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References[edit]

|