SGU Episode 424

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 424 |

|---|

| August 31st 2013 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Guest |

| Quote of the Week |

“A faith that cannot survive collision with the truth is not worth many regrets.” |

Arthur C. Clarke, The Exploration of Space |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

This Day in Skepticism ()

- August 31,1909: Nobelist Paul Ehrlich began the first chemotherapy (a term he coined).

News Items ()

Energized Water ()

Probiotics for Mental Health ()

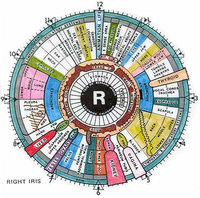

Death by Iridology ()

Immortality ()

Who's That Noisy ()

- Answer to last week: John Mack

Questions and Emails ()

Question #1: Question Authority ()

This week I noticed one of my anarcho-hippie friends’ ”Question Authority!” buttons. I appreciate the skeptical sentiment – obviously we should question whether Saddam Hussein has WMDs or whether God really exists. But some authorities are authoritative – we shouldn’t question the medical establishment on links between HIV and AIDS or the scientific establishment on the reality of anthropogenic global warming. Is there an SGU version of ”Question Authority!” that balances the necessity of open inquiry with the recognition of legitimate authorities? Is it short enough to print on a bumper sticker?Soren RagsdaleUnited Kingdom

Interview with Cara Santa Maria (44:32)

S: We are sitting here at TAM 2013 with Cara Santa Maria. Cara, welcome to The Skeptic's Guide.

C: Thanks for having me.

S: Cara, you are a science communicator, a writer, producer, journalist. You've been on many different shows. Right now you are co-hosting Hacking the Planet with John Rennie,

C: Yep.

S: who's here at the conference with us as well. So how did you get into promoting science?

C: Yeah, you know, it was a weird kind of twist and turn for me. I think it really came out of – my background's not journalism. My background is science. So...

S: What specifically, if I may ask?

C: So, my undergraduate degree is in psychology; and I was a philosophy minor. Then my Master's degree is in neurobiology. I started a PhD in clinical neuropsychology, but I actually kind of fell in love with a boy, dropped out, moved to the west coast, and really, that's when I first started getting involved in science communication. Because looking back at my whole time in graduate school, anybody who's listening who is struggling through graduate school right now knows that they're kind of three things that you're committed to in school.

You need to do your research in the lab; you need to take your courses; then a lot of people also teach for money. And that's really why they do it, for money. I found myself actually not wanting to be in the lab, but really enjoying being in the classroom. So for me, I think it was a pretty easy transition into communicating science for a larger audience because it's sort of the same thing as teaching, just, and kind of the way I did it, it really is the same thing as teaching.

S: Yeah, I agree. I'm from a teacher as well. This to me is all just an extension of teaching.

C: Yeah. Yeah, yeah. Just a little more casually.

S: Yeah.

C: And with more F-bombs.

S: Right, right, right.

B: Is there any particular field of science you gravitate towards? You like communicating besides psychology?

C: Neuro – yeah. I do love the behavior stuff, because it's really interesting, and there's so much woo and pseudoscience. So it's really fun to kind of get into the weeds of it. But for me, I'm also more and more really enjoying communicating physics, even though I'm not particularly good at it, because I get to learn so much along the way. I didn't really study physics in school at all. I took a stellar astronomy class when I was a sophomore in college. But outside of that, it's not my background. So, when I get to interview physicists and ask them interesting questions, I feel like I'm learning along with the audience.

B: I can relate to that.

E: Definitely.

B: That's pretty much where I was, I took astronomy, and the physics of light and color in college, and I loved it, absolutely loved it. But that's the only form of training I've had. Everything else is just what I've read.

J: Yeah, the SGU is a classroom for me as well, our podcast, because we're doing the same thing. We're interviewing a lot of different people; we do a ton of research for our news items every week; and we get a lot of feedback from our listeners too. An expert will write in and say, “Hey guys, you made a couple of minor,

C: Yeah

J: mistakes” or whatever, and it's just this big learning process for us.

C: Yeah, it's huge. I love that too. I loved it when I was working with Huffington Post, and I was working as their science correspondent. I could interview scientists, or sometimes I would do these kind of explainer stories on my own where I did all of my own research, and then I scripted up the whole thing; we just put up animations or images, and I would talk.

So it was always fun to get that feedback from individual scientists, who were like, “Hey! I worked on that project! Maybe we can do an interview.” Or, “Hey! This part was a little off. And this is what it meant.” And there are certain stories that I think, just generally speaking, the media will pick up because they have a flashy topic, or whatever. I remember once going Attack of the Show!, and Horatio Sanz was the guest host. He asked me about this kind of, “Are we all living in a simulation” story that was really big, coming out of Washington. And everybody kept likening it out to The Matrix, “Are we living in the Matrix? Are we living in the Matrix?”

And I tried to avoid that language. I went through and talked about … honestly, I read the paper twenty minutes before I went on air. I didn't really understand it. And that's what I told them. I was like, “I don't really get it, but it seems like what they actually are doing is simulating space-time at the femtometer scale. And they're saying if we could do that, who's to say somebody couldn't be simulating us?” And I actually got an email from the author of the study.

B: Oh, awesome!

C: And he was like, “I'm so glad you said it that way! You're the only person in the media that said it that way!”

E: Awesome!

C: No way!

J: Good for you!

C: That was really cool, but then he gave me an interview, and I ended up turning that into a piece on Talk Nerdy to Me, which was super-fun.

J: Oh, I love that. That's a great title. So you, how long were you at the Huffington Post?

C: I was only there for a year and a half. But I did a lot with them in that amount of time. I was there before they launched their own science page. So I was there through that process of saying, “Listen, we need to have a safe place on the site for research, for evidence-based thinking. We need to have straight science.” Because a lot of the 'science' quote-unquote was living in the Green Pages, in the Tech Pages, and in the Health Pages. And I feel personally that wasn't a very good division there between science that is published in peer reviewed journals, and kind of pseudoey, wooey things.

So I was involved in building up that science page, and then I started doing the Talk Nerdy to Me video series. I wrote a bunch of blogs too, but I think by the end of it, I have a 190 videos.

J: Yeah, that's awesome.

C: Oh, that was crazy. That's a lot of work.

S: I'm curious what it was like to be the science correspondent for the Huffington Post,

C: Sure.

S: which to me is like being the peace minister for the military.

C: Yeah, I know, it's funny.

S: I was actually invited to write for the science section of the Huffington Post, and I turned them down because there was just too much side-by-side,

C: We had a mix of that, yeah.

S: science, and I just couldn't be putting my name next to Dana Ullman and Deepak Chopra,

C: Yeah.

S: and these guys, “You gotta clean up your act, and come back and talk to me.” So how is it going there?

C: So that's a really difficult thing when you're talking about a news organization that's so big. So I remember talking to Alec Shaw about this when I was at Science Online a couple of years ago, which is a kind of meeting of the minds of online science communicators. And he is the science correspondent for The Guardian. And I feel like, they kind of have some of the same issues over at The Guardian.

I think people think of Huff Post maybe because we think of Jenny McCarthy, and we think of Deepak, and those stick out in our minds. But really, when you're talking about a large newspaper, whether it's online or print, that has so many different sections; and a newspaper that started out as a blog! So it's an opinion paper first that then transitioned into delivering news. So anybody from inside understands that the left rail is blog and opinion. Then the middle and the right rail are like vetted news articles. So, it is a difficult thing, right? Because also, the people who run the health pages weren't even in the same building as me! They were in New York , and I was in the Beverley Hills office.

I was working side-by-side with weddings, divorce, and post-fifty, which is like the fifty and over page. Yeah, so I wasn't even anywhere near the health, and I wasn't the editor either. I think that would have been a much more difficult job. David Freeman was my editor. And he did a really good job of having a critical eye of what happened on specifically our pages, which is all we had any control over.

Also – I don't want to call it a turf war, because it's all very friendly – but when you work for a large organization like that, you have carve-outs of what coverage you can do. So, for example, the Green Page existed before the Science Page. So I could never do climate coverage. I could never do any sort of environmental coverage. And the Health Pages existed before, so I had to – it was really a stretch for me to do anything about cancer, for me to do anything. I had to really talk about it like, “Oh no! But I'm talking about a scientific kind of achievement involved in cancer biology, and not so much cancer treatments,” because the Health Pages would say, “Well that's our purview.”

So, it's tough. I know that some scientists, some doctors wanted to speak up and say, “You know what? I'm just gonna, I'm gonna play ball, I'm gonna write on these pages. Phil Plait, I interviewed him quite a few times. Shermer, I interviewed before. Also, I think that I got, I started to gain the trust, specifically with Talk Nerdy as that brand, with a lot of other scientists and communicators, because they felt like I ultimately had control over what ended up going up under my banner, and my name. For me, more important than anything, was to maintain that credibility of the scientific community.

J: That was a great answer.

C: It was! It was a really long answer too, sorry!

J: It's hard. You know, there's a lot of journalists out there like you that get it, and they're there. And there's a lot of journalists that are, they're actually working on stuff they shouldn't be working on,

C: Sure.

J: people that are on the science beat, that aren't scientists, or get science.

C: Yeah.

J: And it's frustrating for us, because we try to popularize science; we're there. We're also huge into the skeptical community and critical thinking, and we have a very good perspective on what's good and what's not good.

C: Yeah.

J: And I just was talking to another journalist yesterday, and he's like, “We're not all bad.” And I'm like, “I know.”

(Cara laughs)

J: But a lot of it is bad.

C: Yeah.

J: And we're worried about it, because that's what people are reading. That's what's getting into peoples' heads.

C: What's so sad is that what we're seeing so little money going into journalism any more. It's so hard for these papers to stay afloat. So now we've got for-profit journalism, which is a huge problem in this country, especially when we're talking about on-air TV news, which is a whole different argument.

But also, you're saying that there is no science desk any more at these papers. There is no environment desk. You've got people who usually would have a very specific beat, and have trained their whole lives covering that beat, who are having to cover topics that maybe they're not really equipped to cover.

Pair that with this old-school journalistic model of “You've always got to give equal time to both sides,” quote-unquote - you can't see my air quotes, but I'm making them – of an equation, or of a problem. And right there, you just have a recipe for false equivalencies left and right, which are so dangerous.

J: Exactly! That's so right, yeah. The equal footing thing is total BS.

C: And it's like, I feel like, “Okay, if you're a news organization, and you feel like you want to have different opinions - or different view points I should say – on your air, I will make a direct correlation between the amount of consensus, and the amount of air time I will give them.

B: Yes.

C: So I will give a climate denier five percent of my air time, so then as to make fun of them, once I get them off the air. Or whatever the case may be. Or, let's say point five percent. I don't even know what the consensus is. In this country, it's probably a little lower because we have climate scientists on the payroll of big oil. So it's...

S: Ninety seven percent is the figure that comes up.

C: So there you go. So we'll give a climate-denying scientist three percent of our air time

S: Yeah.

C: so as to show that three percent of these climate scientists are paid by BP.

J: Yeah, exactly.

B: I like it.

J: It's reasonable.

C: Yeah.

S: What's your thoughts on the utility, of the impact of new media versus traditional media in terms of getting the message out, promoting science, and just generally educating the public?

C: I think new media's huge; and I think that I'm kind of the embodiment of new media. Like, I'm a freelancer now, and I do a lot of on-air work. And I still feel like when it comes to all the different news organizations. I just did some really fun work with Al Jazeera America, who recently acquired Current. And I worked on a fun innovation show there, which is very science friendly.

And I have done some really traditional media, but I think I'm still kind of scary to traditional media outlets. Whenever my agent sends me out, and I'm talking to anybody at CNN, I'm like, “Are we wasting our time here?” You know? I'm not CNN.

S: Why is that?

C: I don't have pretty-lady reporter hair, and I've got a lip ring, and I'm kind of irreverent. And I just think that we're still not quite in this place where …

B: You're too hip is what you're saying.

C: A little too hip.

S: Yeah.

C: No, I think I'm a little scary. But new media, it's easy! Anything I do on YouTube, I've done Wil Wheaton's TableTop show, and I've done a bunch of stuff with The Nerdest. And I did some stuff with Stanley, which is fun because then you get these cross-over audiences. And you can speak to them in that way.

But I do think that there's a fear and a risk of journalism only going the way of citizen journalism and new media. I understand it. I look at traditional reporters and editors, and their concern is about the editorial process. It's about curation. It's about helping to separate the meat from the fat. And I think we're living in kind of fire hose land right now, where there's so much stuff available to us. It becomes more difficult for the casual observer to know the difference between science and pseudoscience, or to know the difference between journalism and pseudo-journalism.

J: It's delivered in the same way. Again, I was having a great conversation with some one yesterday; and we were talking about the idea that there isn't the editorial processes in place any more. It's like anybody can start a blog.

C: Yeah.

J: And then there's this idea – Steve and I talk about this all the time where this equal-footing idea or whatever. Like, no! You're wrong! We don't say that any more.

C: Yeah, and as an observer, as a viewer, as a listener, as a watcher of … I think that the onus starts to fall on your own shoulders to … let's say for example, I don't have a Google reader. And I'm a reporter. I'm not actively working as one right now.

S: Google Reader was shut down.

C: Right. And Google Reader shut down anyway! So I was ahead of the curve on that. But I use Twitter, as my reader. It's very important to me. I am very specific about the people I follow. I kind of apologize in advance if we're friends, and you follow me, but I'm not following you back, because I follow people on Twitter to get my content. That's the reason I do it.

And I keep it at 250. When there's somebody new I feel like I need to follow, I'll usually axe another person. It's really because I can't handle any more than 250 people that I'm following. But that becomes my reader. And it's a curated list by me of people who I trust, people who have shown me throughout that they are delivering quality vetted content.

J: Exactly. We've all gone through that process.

C: And it's tough! And I think a lot of casual consumers of the news or of information don't have time. And I also have a background in science. I understand the scientific method, and I've been a journalist for coming up on two years. So I have some training in that, but I can't imagine how difficult it would be to know the difference between the bullshit out there and the legitimate news.

J: Yeah, it's scary! It's a wild west.

C: It really is.

J: As we've said many times,

E: Open range.

C: Yeah.

J: And what do you do? Do you hand out your list of 250 and say, “Hey guys, you want legitimate sources?” Would that even help?

C: Yeah, I think, you try, you follow Friday on people. You talk about people, and you collaborate with people in the media. I think what happens is that you have these little niche grassroots groups of people that are interested in consuming very specific content. But we also live in a world now where you can get the news that's fit for you. You don't have to ever hear anything outside of your own opinion.

J: That's true, yeah. That is scary.

C: Yeah! You can completely – and you'll feel, you'll have this false sense of security that you are an informed citizen; and you are making good decisions when you show up for the polls. And really it's just because you're living in an echo chamber.

E: Lots of confirmation bias slips in that way.

C: A whole lot.

S: It goes beyond politics. The echo chamber effect we encounter everywhere now on the internet. We talk about, go to anti-vaccination sites, and the comments is a manufactured echo chamber. Specifically, and they rationalize it by saying, “We need a safe place to talk to other people.” And if you disagree with them, you're a troll!

Well there are real trolls on the internet, but not everybody who disagrees with you is a troll. But you can see how very quickly and instantly you can create an echo chamber online.

C: Completely! And it's so funny, because, then let's say we sit here at this skeptic convention, and we try to empathize let's say with individuals who are hanging out in an anti-vaxx chat room. And this is a mom who happened to have her children vaccinated who also happened to have an autistic child. And the signs of autism happened to show up around the same time of vaccination, which is a very common story that we hear.

Obviously, there's no link. But in her mind and her heart, that anecdote is really strong because it's her life. It's her story. So she's in this anti-vaxx chat room. She's not some nefarious perpetrator. She's not writing these brochures or whatever. And they're saying, “This is a safe place. This is where like-minded … because we're the informed ones.”

Cut to all of us sitting around a table at a skeptic convention saying, “We're all together because we're the informed ones.” And it's really difficult I think for people to know the difference between – how is what we're doing any different from what they're doing? For us, we say, “Well, it's based on available evidence.”

But when you grew up in a broken school system, and when you are struggling and working three jobs to raise your kids as a single mom, you don't have time to be informed the way that we were lucky enough – it's a luxury. Scientific thought, it's a luxury. I personally think it's a necessity as well, and that's why I'm really crusading I think for helping to improve science literacy in this country specifically. But we're the lucky ones, because we get to think that way.

J: Exactly, yeah.

S: Although I do want to add, actually answer your question. What's different about us. I do get concerned that we get into an echo chamber ourselves. But I do think that there's a couple of important differences. Let me know what you think about this. One is that we focus on process and not conclusion.

C: Sure

S: Whereas the anti-vaxx, it's about the conclusion. It's about being anti-vaxx. And the second is we seek out the other side. I want to hear the other side. I don't accept anything until I've fully explored every point of view, which again is the exact opposite. So, do you...

C: I agree. I think that that's a legitimate difference. And I think that procedurally, you're completely right. But I think that there's also this point of – I don't want to say of no return, because the whole point of the scientific method is that you can always return – but there is this point – and I talked about this earlier – I can't remember to whom – where it's an issue of burden of proof, right?

So when you are talking about the difference between a hypothesis and a theory, and hopefully your viewers know the difference. But the long and short of it is, you're observing your environment. You're interacting with it. A question comes to mind. You ask yourself that question. You come up with a way to test that. Then you have some new observations. You can either refute or support your hypothesis.

More people start doing that in multiple fields, and asking questions that are closely related, and eventually start to get this body of knowledge, right? And that's a theory, is when a body of knowledge kind of fills up.

And once you have a pretty well-established theory, and we're talking thousands of peer-reviewed papers, all of a sudden, it's not my job to try to quote-unquote, “prove” to you any more why evolution is fact. If you're an anti-evolutionist, you need to give me evidence as to why you think that my theory is flawed. The burden of proof has shifted a little bit.

S: Yeah.

C: And I think when it comes to – even in the skeptic community – we know that the climate is getting hotter, and we know that the reason for that is largely because of human activity. We know that there is no legitimate link between vaccines and autism. But because of that, we stop listening to the other side, because we're like, “You've had your chance to show us.”

And I think you almost start to say, like, “Any new piece of quote-unquote “evidence” is probably bullshit.” The nice thing is, there are crusaders in this community who really do comb over all of that evidence.

S: Yeah.

E: Oh sure.

C: They look at all of it; they categorize it; they tell you why they see flaws in the study designs, or whatever, which is great. But I don't have time to do that!

J: Absolutely!

C: You've got to show me why. I don't have time to figure it out for myself.

S: But I think you more described what scientists do, not what skeptics do.

C: Sure.

S: Because I think scientists get that once you're beyond a certain threshold, everything else is bullshit, and don't waste my time with it! Whereas the skeptics are still like, “Okay, them psy research, let's dig deep. I know ESP's bullshit; we've known for a hundred years. But let's dig deep on this new latest version of the claim.” Because that's what we do! That's our job.

C: And that's fair. I'm glad you do it. I consider myself a skeptic as well, but maybe I'm a lazier skeptic, because that sounds exhausting to me.

S: Well, we divide and conquer. We all have our specialty.

C: I guess.

E: We do. And because the mother of three, as you described earlier, doesn't have the time to do that, we are sort of helping them bring that information forward for them.

S: Well, Cara, thank you so much for joining us. We really appreciate you sitting down with us and spending some time.

C: Thanks for having me.

J: Thanks Cara.

E: Thank you.

B: Thank you.

Science or Fiction (1:04:03)

Item #1: Acids taste sour, while bases taste bitterhttp://www.elmhurst.edu/~chm/vchembook/180acidsbases.html Item #2: The pH of spinal fluid averages from 4.5-5.5, mainly from the presence of carbonic acid. Item #3: In a study of 20 soft drinks, RC cola was found to be the most acidic at a pH of 2.4. Item #4: The world’s strongest acid, carborane, which is a million times more potent than sulphuric acid, is also one of the least corrosive.

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()

“A faith that cannot survive collision with the truth is not worth many regrets.”- Arthur C. Clarke, The Exploration of Space

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|