SGU Episode 183: Difference between revisions

m (edited infobox) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

B: Ouch. | B: Ouch. | ||

R: Can we all just stop and think about the great sacrifice I'm making for you all by being on the show at 2 AM? | |||

S: Alright that's long enough. | |||

(laughter) | |||

== News Items == | |||

=== The Holographic Universe <small>(2:33)</small>=== | |||

S: So Bob, you got the first news item this week. Tell us about the holographic universe. | |||

J: Oh god. | |||

B: Yeah, Jay, I did some preliminary talking about this. This one is really fascinating. I had a really good time researching this. But hold on to your beanie hats with the propellers on them. This one's pretty wicked. | |||

R: I'm sorry, Bob, I don't have my beanie hat with a propeller on it so can I hold on to something else? | |||

J: Yeah, just put your hand on Sid's face right now. | |||

(laughter) | |||

S: Rebecca, what does your beanie hat have on top of it? | |||

R: I can't say on a family podcast. | |||

S: Okay, use your imagination. | |||

B: Well, scientists may have actually detected the grain of the universe. This may mean that our reality, everything we see and do, our entire universe, in fact, is like a 3 dimensional holographic image of sorts projected from somewhere else. Talk about a one two punch. This one was very very interesting. The whole story starts with a German British gravity wave detector called the GEO 600 in northern Germany. They have been trying to find, for 7 years, Einstein's theorized gravity waves and they haven't found them yet but they have run into a relatively big problem. Their detector keeps getting this background noise that will not go away. They've tried every way to rule it out. This is subtle background noise that's been plaguing them. | |||

J: Bob, did they turn the fan off? | |||

(laughter) | |||

B: Yeah, right. At this point Craig Hogan enters the picture. He's a physicist at Fermilab, particle physics lab in Batavia, Illinois and he was recently appointed as the director of Fermilab's Center for Particle Astrophysics. He's been thinking about this really interesting principle called the holographic principle. It's a little complicated but the idea is that the total amount of information or entrophy that a space can contain depends on the surface or the boundary of that space and not the volume of that space. You see what I mean? So as an analogy, think of the plastic used in a beach ball being directly related to the amount of information inside the beach ball. So its not the volume of the beach that matters but there's a relationship between the surface on the outside and the inside. There's a direct almost a one to one correspondence. | |||

S: That's a little counter intuitive. I'm sure that there's a mathematical reason for that. | |||

B: Well, you nailed it exactly. The mathematical principle actually works extremely well with the entropy of black holes. In 1972, a physicist Jacob Bekenstein discovered that the black hole's entropy or information content is proportional to the surface area of the event horizon, which is essentially the holographic principle. The idea here is that the progenitor star, the star that exploded to become that black hole, all of the information about the 3 dimensional structure and everything about that star is encoded in the 2 dimensional event horizon. So that's basically the idea of this holographic principle. | |||

J: What? | |||

B: In the 1990s, 2 other physicists, you've got Susskind and 't Hooft, they extrapolated this whole principle from the black hole's event horizon to the cosmological horizon of the universe. It's essentially the boundaries of our observable universe. So they kind of extrapolated it to the entire universe. So this would mean that the universe could essentially be described as a 2 dimensional construct embedded in the boundaries of the horizon of the universe. | |||

J: I don't get this at all. | |||

B: Okay, let me just continue this thought then. So then our visible universe could then be seen as a 3 dimensional representation of processes that are happening on this 2 dimensional surface. | |||

J: Is the universe in 3 dimensions or not? | |||

Revision as of 08:34, 12 November 2012

| This episode is in the middle of being transcribed by Gugarte (talk) as of {{{date}}}. To help avoid duplication, please do not transcribe this episode while this message is displayed. |

| SGU Episode 183 |

|---|

| 21st January 2009 |

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

The scientific tradition is distinguished from the pre-scientific tradition in having two layers. Like the latter, it passes on its theories; but it also passes on a critical attitude towards them. The theories are passed on, not as dogmas, but rather with the challenge to discuss them and improve upon them. |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| SGU Podcast archive |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today's Wednesday, Jan. 21th 2009, and this is your host Steven Novella, president of the New England Skeptical Society. Joining me this evening are Bob Novella,

B: Hey everybody.

S: Rebecca Watson,

R: Hello everyone.

S: Jay Novella,

J: Hello gov'nor.

S: and Evan Bernstein.

E: And on this date, today, in 1677, the first medical book was published in the United States.

R: What medical book was that, Evan?

E: A pamphlet concerning the smallpox disease.

R: That's amazing.

E: I hope they get that cured sometime soon.

S: Oh yeah.

E: It's only been 330 years.

R: Now, we will be getting rid of that any moment now.

(laughter)

J: You know they didn't have autism back then.

(laughter)

S: Yeah, they didn't have any of the diseases they hadn't discovered and named yet.

(laughter)

E: Isn't that incredible?

S: Right.

J: So Rebecca is in London right now with Sid.

R: I'm in London. Yes.

J: That's why she said hello with an English accent and I had to respond because I'm like, you know, Pavlov's dog.

R: I was only like goading you.

J: I know. I can't help myself.

(Rebecca laughs)

S: So how are our fellow skeptics from across the pond, Rebecca?

R: I think everyone on this side of the Atlantic is fantastic and it's been a really great week so far. I did London Skeptics in the Pub on Monday and that was fantastic. I saw a lot of Skeptics' Guide friends and guests you guys know like Simon Singh was there and John Ronson who we hadn't had on the show yet but we will. He's my super best friend and he's awesome. Tim mentioned King and he was a lot of fun. Great musician. And Ben Goldacre was there. You guys met him at TAM.

S: Oh yeah.

J: Oh cool.

R: Yeah, it's been a lot of fun. I miss you guys, though.

J: Cool.

R: Yeah.

S: Yeah, we miss you last week.

R: I was really bummed to miss last week because I didn't think I was gonna be able to make it this week. I mean, it is 2am right now here in London.

S: Yeah.

B: Ouch.

R: Can we all just stop and think about the great sacrifice I'm making for you all by being on the show at 2 AM?

S: Alright that's long enough.

(laughter)

News Items

The Holographic Universe (2:33)

S: So Bob, you got the first news item this week. Tell us about the holographic universe.

J: Oh god.

B: Yeah, Jay, I did some preliminary talking about this. This one is really fascinating. I had a really good time researching this. But hold on to your beanie hats with the propellers on them. This one's pretty wicked.

R: I'm sorry, Bob, I don't have my beanie hat with a propeller on it so can I hold on to something else?

J: Yeah, just put your hand on Sid's face right now.

(laughter)

S: Rebecca, what does your beanie hat have on top of it?

R: I can't say on a family podcast.

S: Okay, use your imagination.

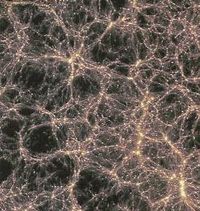

B: Well, scientists may have actually detected the grain of the universe. This may mean that our reality, everything we see and do, our entire universe, in fact, is like a 3 dimensional holographic image of sorts projected from somewhere else. Talk about a one two punch. This one was very very interesting. The whole story starts with a German British gravity wave detector called the GEO 600 in northern Germany. They have been trying to find, for 7 years, Einstein's theorized gravity waves and they haven't found them yet but they have run into a relatively big problem. Their detector keeps getting this background noise that will not go away. They've tried every way to rule it out. This is subtle background noise that's been plaguing them.

J: Bob, did they turn the fan off?

(laughter)

B: Yeah, right. At this point Craig Hogan enters the picture. He's a physicist at Fermilab, particle physics lab in Batavia, Illinois and he was recently appointed as the director of Fermilab's Center for Particle Astrophysics. He's been thinking about this really interesting principle called the holographic principle. It's a little complicated but the idea is that the total amount of information or entrophy that a space can contain depends on the surface or the boundary of that space and not the volume of that space. You see what I mean? So as an analogy, think of the plastic used in a beach ball being directly related to the amount of information inside the beach ball. So its not the volume of the beach that matters but there's a relationship between the surface on the outside and the inside. There's a direct almost a one to one correspondence.

S: That's a little counter intuitive. I'm sure that there's a mathematical reason for that.

B: Well, you nailed it exactly. The mathematical principle actually works extremely well with the entropy of black holes. In 1972, a physicist Jacob Bekenstein discovered that the black hole's entropy or information content is proportional to the surface area of the event horizon, which is essentially the holographic principle. The idea here is that the progenitor star, the star that exploded to become that black hole, all of the information about the 3 dimensional structure and everything about that star is encoded in the 2 dimensional event horizon. So that's basically the idea of this holographic principle.

J: What?

B: In the 1990s, 2 other physicists, you've got Susskind and 't Hooft, they extrapolated this whole principle from the black hole's event horizon to the cosmological horizon of the universe. It's essentially the boundaries of our observable universe. So they kind of extrapolated it to the entire universe. So this would mean that the universe could essentially be described as a 2 dimensional construct embedded in the boundaries of the horizon of the universe.

J: I don't get this at all.

B: Okay, let me just continue this thought then. So then our visible universe could then be seen as a 3 dimensional representation of processes that are happening on this 2 dimensional surface.

J: Is the universe in 3 dimensions or not?

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by the New England Skeptical Society in association with the James Randi Educational Foundation and skepchick.org. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at www.theskepticsguide.org. For questions, suggestions, and other feedback, please use the "Contact Us" form on the website, or send an email to info@theskepticsguide.org. If you enjoyed this episode, then please help us spread the word by voting for us on Digg, or leaving us a review on iTunes. You can find links to these sites and others through our homepage. 'Theorem' is produced by Kineto, and is used with permission.

|