SGU Episode 481: Difference between revisions

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ||

== This Day in Skepticism <small>()</small> == | S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptic's Guide to the Universe. Today is | ||

Wednesday, September 24, 2014 and this is your host, Steven Novella. | |||

Joining me this week are Bob Novella... | |||

B: Hey, everybody. | |||

S: Rebecca Watson... | |||

R: Hello, everyone. | |||

S: Jay Novella... | |||

J: Hey, guys. | |||

S: And Evan Bernstein... | |||

E: Hi folks, how are you all tonight? | |||

B: Doing good, Evan. | |||

J: All right, yeah. | |||

== This Day in Skepticism <small>(0:29)</small> == | |||

R: Happy birthday to the answering machine, which was invented on | |||

September 27, 1950! Now, for the bulk of our audience, I will now | |||

describe what an answering machine is. | |||

''(laughter)'' | |||

R: An answering machine was a little box that you used to plug your | |||

phone in to, and when you weren't there at home, because you couldn't | |||

take your phone with you back then, the answering machine would pick | |||

up and people would leave messages, and it was very exciting. We | |||

would leave prank messages sometimes, we would have prank recordings | |||

on our answering machines. | |||

J: Yeah, you mean the outgoing message was the prank too. | |||

R: Yeah. Yeah, it was a time of pranks. | |||

E: Oh, I hated that one where someone would say "Hello?" and then wait a | |||

few seconds (you're speaking to the answering machine) and then you | |||

say something and it says "Oh yes, hi, how you doing?" and then | |||

another pause and you think you're speaking to someone but it's a damn | |||

answering machine. Hated it. | |||

J: ''(laughs)'' | |||

B: And don't forget, this wasn't saved to a hard drive or a solid | |||

state drive, this was like a cassette tape that all of this action is | |||

happening on. ''(laughs)'' | |||

E: I bet you in the 50's it was some reel-to-reel device that took up | |||

three rooms like UNIVAC or something. | |||

R: I found on a website that the answering machine was invented on | |||

this day in 1950, but I've also found elsewhere that the first | |||

commercial answering machine went on the market in 1949 ''(laughs)'', | |||

uh, and that was called the Tel-Magnet. And the problem is that I'm | |||

in the midst of moving house, and I could not suss all this stuff out | |||

before we'd started this recording. So I'll mention that and I'll | |||

also mention--and I think this came up in a previous Science or | |||

Fiction years and years ago or something{{Link needed}}--but, really, | |||

the first answering machine was invented in 1898 by a man named | |||

Valdemar Poulsen and this was basically a recorder that was used for | |||

recording conversations on the telephone. And it was the basis for | |||

what eventually became the mass-produced answering machine. So... | |||

S: Right. | |||

R: ...a dubious day in history, but, you know, I'm going with it. | |||

E: ''(laughs)'' | |||

S: But the first, from what I'm reading, the first commercially | |||

''successful'' answering machine was the Ansafone in 1960 in the | |||

United States. Yeah, the Tel-Magnet, 1949, was recorded a message on | |||

a magnetic wire... | |||

B: Whoa. | |||

S: ...that sold for $200... | |||

E: That's worth it. | |||

S: ...but was not, not a commercial success. | |||

R: You know, I remember when there was a short period where cell phone | |||

companies would charge you just for voicemail, for like a dollar a | |||

month... | |||

S: Mm hm. | |||

R: ...and I just found that ridiculous ''(laughs)''. I can't even | |||

imagine a $200 answering machine. | |||

S: The telephone is definitely one of those things that has changed | |||

consistently over the years and you could, like, tell, like you can | |||

date a movie by the phones. | |||

R: Oh yeah, absolutely. | |||

S: Yeah, pretty well. Even, as well as you can, say, with computers, | |||

you know. | |||

R: I've done that several times where I'm watching a film and, you | |||

know, sometimes a film will be set in a certain period but they don't | |||

come out and tell you right away... | |||

E: Mm hm. | |||

R: ...like a lot of indie films will do that, and I'm really just | |||

always looking for telephones so I can figure out exactly when it's | |||

supposed to be. | |||

E: Within a few years accuracy, yeah. | |||

== News Items == | == News Items == | ||

=== Nvidia Debunks Moon Hoax <small>()</small> === | === Nvidia Debunks Moon Hoax <small>(3:47)</small> === | ||

* http://www.theskepticsguide.org/nvidia-debunks-moon-landing-conspiracy-theory | * http://www.theskepticsguide.org/nvidia-debunks-moon-landing-conspiracy-theory | ||

=== GMO Feeding Trial <small>()</small> === | S: Well, Jay, this is one the coolest things I think I've seen this | ||

week, or even for a while. It's a very interesting ad campaign by | |||

Nvidia, the graphics card maker. Tell us about it. | |||

J: Yeah, it was very cool, Steve, I mean, I absolutely love that era | |||

of space exploration, you know, the 1960's/early 1970's, just the | |||

whole look of that series of missions the United State did. To me, | |||

it's like one of my favorite historical moments. I love World War II, | |||

I love space exploration in that decade, just awesome. | |||

So, back in July 16, 1969, the Apollo 11 launched to the Moon. Buzz | |||

Aldrin and Neil Armstrong were the lucky guys selected to land on the | |||

Moon and actually walk on the Moon. A lot of people think it was | |||

faked, and they make a lot of remarks about why it wasn't real, and | |||

this is some of the remarks that come out. So, a common claim is that | |||

no stars were visible in a lot of the pictures or all the pictures | |||

that were taken on the lunar surface. That the shadows on the Moon | |||

make no sense. Also, I heard that people believe that the way the | |||

astronauts actually move, the way that they jumped around on the lunar | |||

surface. | |||

There's probably a couple of dozen points out there that people have | |||

brought up over several past decades, trying to refute the idea that | |||

we did or did not land on the Moon. The fact is, I'm going to break | |||

it to you know, that, yes, the United States did land on the Moon. It | |||

landed on the Moon more than once. There's artifacts on the Moon. By | |||

use of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, they've seen not only | |||

leftover space vehicles and other things, but they actually can see | |||

the footprints of the astronauts, like these long single-file | |||

footprints that the astronauts left as they were... | |||

E: That's cool. | |||

J: Yeah, isn't that awesome? You can see exactly where they went, | |||

because really, arguably, it hasn't changed really at all, because | |||

there's no weather or much activity happening on the Moon other than | |||

stuff flying in from outer space. | |||

So, Nvdia created a new chip called the Maxwell, and the team that | |||

developed this, developed a way to show off this chip. They created a | |||

3D software technology that allows them to bounce light off of all of | |||

the rendered objects much more accurately than anybody's ever done | |||

before. And this is one hell off an achievement because the processor | |||

power needed and the software needed is incredible, it's just, you | |||

know, something that hasn't really been achieved to this level of detail | |||

before. And I don't even think we've gotten even close to this level | |||

of detail before. | |||

The engineers had to model every 3D object that they found on the | |||

Moon. So, that includes the spacecraft, the astronauts, the lunar | |||

soil, the rocks, any objects that were on the lander that were | |||

reflecting light. They were actually simulating detail down to what | |||

kind of materials were used to help simulate the actual effects of | |||

light bouncing off of it. | |||

So, they selected a very popular picture of, now I believe that Neil | |||

Armstrong was already on the surface, and this was a picture of Buzz | |||

Aldrin getting out of the lunar lander, and Neil Armstrong was taking | |||

the picture. So, you see, it's a very iconic picture of an astronaut | |||

coming down the ladder right before they touched the ground. Now this | |||

was the picture that they decided to duplicate. | |||

So, here's a little bit of their process. They had to figure out how | |||

the light actually reflects on the Moon differently than here on | |||

Earth. Now, one thing to keep in mind is that light doesn't simply | |||

just come in straight lines from the light source, say, in the room | |||

that you're in. If you look at the light source in your room, right, | |||

just turn my head and looked up at the light on the ceiling. You | |||

know, light, of course, is just coming in a perfectly straight line | |||

from that light source to me. But it's also hitting almost | |||

everything, if not everything, else that I'm sitting in the room | |||

with. And those objects are reflecting light to me and on other | |||

objects, which then again reflect light to me. Right, and it just | |||

keeps going, the amount of reflections, I bet, it would be interesting | |||

to do a calculation on just how many reflections are happening, how | |||

much of that light, how many times did it bounce before it actually | |||

gets to you. | |||

And that gives a room, or a space, or any kind of area, a particular | |||

kind of illumination. And the illumination that a lot of people saw | |||

on the Moon in the photographs seemed very strange to them. But, | |||

there's a lot of significant differences between the Moon and the | |||

Earth. You know, in particular, the Moon does not have an | |||

atmosphere. And that does a very dramatic thing to the way that light | |||

looks on the moon. It looks a lot more stark, there isn't any | |||

diffusion happening, meaning that the light that's coming in through | |||

the Earth's atmosphere, it gets scattered, and it softens the light. | |||

And on a cloud-covered day, if you notice, if you take pictures | |||

outside on a cloud-covered day, you can get some of the best pictures | |||

outside because what's happening is all that sunlight is hitting the | |||

tops of the clouds and the clouds are diffusing the light a lot, and | |||

it makes everything look really soft. You can take very nice pictures | |||

without any harsh shadows on somebody's face and everything, it's very | |||

evenly lit. | |||

The Moon is the exact opposite of that. The Moon, there is no evenly | |||

lit nothing on the Moon. You know, the vast majority of everything | |||

has a very, very bright light on it or it's almost completely in the | |||

dark. However, that being said, objects are bouncing a lot of that | |||

really harsh light very powerfully in all directions. So, when the | |||

team took into account, as they're trying to simulate this picture, | |||

all the different reflections and the different surfaces and the | |||

textures on those surfaces and how reflective are they and what | |||

direction are those different light rays going to be bouncing in, they | |||

did a simulation of the astronaut getting out of the lunar lander. | |||

And it looked good, but it didn't look exactly like what they | |||

expected, and they're like "Well, the astronaut isn't as lit up in | |||

this picture as we expected the astronaut to be to simulate the | |||

original picture" so they were saying that the astronaut just was | |||

dimmer than in the original picture. | |||

So, they figured out they completely forgot to factor in the | |||

photographer, which I believe was Neil Armstrong, taking a picture of | |||

Buzz Aldrin. And when they put his space suit into the 3D rendering, | |||

bounced light off of it, there was so much light coming off of that | |||

space suit because of how reflective it was, and if you remember those | |||

guys were wearing almost stark white space suits, they were reflecting | |||

light like crazy. And the material that they were made out of as well | |||

was very reflective. They popped that space suit in there, and all of | |||

sudden, the picture looks almost identical, their 3D rendering looks | |||

almost identical to the original picture. | |||

Take a look at the image guys, you can see it anywhere online, just | |||

look up "nvidia maxwell moon" or "nvidia moon", you'll be able to find | |||

lots of different images of this. And it's amazing how close that | |||

they got. | |||

S: Now, Jay, just to point this one thing out. The Moon hoax | |||

conspiracy theorists have argued that in this very picture, because | |||

Buzz Aldrin is in the shadow of the lander, the he should be basically | |||

black, that you shouldn't be able to see him at all, because of the | |||

lack of diffusion, because they are not taking into consideration the | |||

interreflections. Especially the biggest one of which is Neil | |||

Armstrong himself who's just this bright light source shining back on | |||

Buzz Aldrin. So this completely blows that out of the water. | |||

J: That's right, Steve. Neil Armstrong was actually standing far | |||

enough away from the lunar lander where he had direct sunlight hitting | |||

him, and he, in essence, was like a light reflector... | |||

S: Yeah. | |||

J: ... If you've done any kind of photography or film, you know, use a | |||

mylar reflector to bounce light. And he was that times five, because | |||

of the material and because of how large he is, he was like a huge | |||

flashlight lighting up Buzz Aldrin as he was coming down the ladder. | |||

Yeah, so, another thing people are saying about this experiment that | |||

Nvidia did was it's yet another way of, in essence, debunking those | |||

lunar lander critics or the people that don't believe it, that don't | |||

believe we landed on the Moon. Because they couldn't have produced | |||

the lunar environment and they couldn't have taken pictures with that | |||

kind of lighting, they couldn't have simulated that in a studio. It | |||

just would not have been feasible for a lot of reasons and this | |||

experiment that was done by the Maxwell team at Nvidia proves it. So | |||

there's another example of how there was no way that they had the | |||

technology 40--50 years ago to fake the Moon landing. | |||

S: Yeah, I mean, essentially, in 1969, they would have had to, if they | |||

shot this a studio, they would have had to simulate the lighting on | |||

the Moon in such a way that it would have withstood a recreation 45 | |||

years in the future with advanced graphics computer technology they | |||

could not possibly have anticipated would exist. If there were stage | |||

lights or anything else going on in here then the rendering, the | |||

Nvidia rendering wouldn't have worked. | |||

E: Right. | |||

S: It wouldn't have simulated... | |||

E: It would have revealed something different. | |||

S: Yeah, it would have shown something different. | |||

J: So, in essence, what I'm saying is that we need to spend money to | |||

go back to the Moon. | |||

S: Yeah. | |||

''(laughter)'' | |||

E: Hear, hear. | |||

S: We, I do also want to point out that they used their graphics card | |||

also to increase the exposure of the photos on the surface of the | |||

Moon. | |||

J: Oh yeah, that was cool. | |||

S: And the, so the other argument is "Why are there no stars in the | |||

sky?" | |||

E: Oh, God. | |||

B: Oh, God, that's the worst. | |||

S: And the answer is 'cause it's daytime. You know, people think, | |||

"Oh, the sky's black. On Earth, the sky is black at night and so you | |||

should see the stars." But it's still daytime on the Moon when | |||

they're filming, and all that light is just washing out the stars, the | |||

stars are too dim. But, with their technology, they increased the | |||

exposure and, you know, so of course anything the lunar surface, | |||

anything on the lunar surface becomes total whiteout, but the black | |||

lunar sky, it becomes light enough where you can see the stars. The | |||

stars come out. So they are there. The stars are there in the | |||

background, you just can't see them because of the exposure. | |||

B: Oh my God, so they're actually detectable to prove that they are | |||

there. | |||

S: Yes. | |||

B: That's epic. | |||

E: ''(laughs)'' That's not going to convince any of the hoaxers, | |||

though, I mean, right? | |||

R: Well, nothing's going to convince them. | |||

E: They're not going to buy that. | |||

J: No, I don't think so, Ev. | |||

S: Yeah. Well, once you buy the conspiracy, then evidence becomes | |||

irrelevant, because the government, I wonder how much the government | |||

paid Nvidia to fake this, you know, to cover up their 45-year-old | |||

conspiracy. | |||

E: Exactly, it just goes and goes and goes. | |||

S: Yep. All right, thanks Jay. | |||

=== GMO Feeding Trial <small>(14:27)</small> === | |||

* http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/19-years-of-feeding-animals-gmo-shows-no-harm/ | * http://theness.com/neurologicablog/index.php/19-years-of-feeding-animals-gmo-shows-no-harm/ | ||

Latest revision as of 00:59, 10 October 2014

| This episode needs: transcription, time stamps, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 481 |

|---|

| September 27th 2014 |

|

| (brief caption for the episode icon) |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

R: Rebecca Watson |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

'If all your friends jumped off a bridge, would you jump too?' 'Oh jeez. Probably.' 'What!? Why!?' 'Because all my friends did. Think about it — which scenario is more likely: every single person I know, many of them levelheaded and afraid of heights, abruptly went crazy at exactly the same time… …or the bridge is on fire?' |

Randall Munroe (xkcd) |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction

You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptic's Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, September 24, 2014 and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody.

S: Rebecca Watson...

R: Hello, everyone.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey, guys.

S: And Evan Bernstein...

E: Hi folks, how are you all tonight?

B: Doing good, Evan.

J: All right, yeah.

This Day in Skepticism (0:29)

R: Happy birthday to the answering machine, which was invented on September 27, 1950! Now, for the bulk of our audience, I will now describe what an answering machine is.

(laughter)

R: An answering machine was a little box that you used to plug your phone in to, and when you weren't there at home, because you couldn't take your phone with you back then, the answering machine would pick up and people would leave messages, and it was very exciting. We would leave prank messages sometimes, we would have prank recordings on our answering machines.

J: Yeah, you mean the outgoing message was the prank too.

R: Yeah. Yeah, it was a time of pranks.

E: Oh, I hated that one where someone would say "Hello?" and then wait a few seconds (you're speaking to the answering machine) and then you say something and it says "Oh yes, hi, how you doing?" and then another pause and you think you're speaking to someone but it's a damn answering machine. Hated it.

J: (laughs)

B: And don't forget, this wasn't saved to a hard drive or a solid state drive, this was like a cassette tape that all of this action is happening on. (laughs)

E: I bet you in the 50's it was some reel-to-reel device that took up three rooms like UNIVAC or something.

R: I found on a website that the answering machine was invented on this day in 1950, but I've also found elsewhere that the first commercial answering machine went on the market in 1949 (laughs), uh, and that was called the Tel-Magnet. And the problem is that I'm in the midst of moving house, and I could not suss all this stuff out before we'd started this recording. So I'll mention that and I'll also mention--and I think this came up in a previous Science or Fiction years and years ago or something[link needed]--but, really, the first answering machine was invented in 1898 by a man named Valdemar Poulsen and this was basically a recorder that was used for recording conversations on the telephone. And it was the basis for what eventually became the mass-produced answering machine. So...

S: Right.

R: ...a dubious day in history, but, you know, I'm going with it.

E: (laughs)

S: But the first, from what I'm reading, the first commercially successful answering machine was the Ansafone in 1960 in the United States. Yeah, the Tel-Magnet, 1949, was recorded a message on a magnetic wire...

B: Whoa.

S: ...that sold for $200...

E: That's worth it.

S: ...but was not, not a commercial success.

R: You know, I remember when there was a short period where cell phone companies would charge you just for voicemail, for like a dollar a month...

S: Mm hm.

R: ...and I just found that ridiculous (laughs). I can't even imagine a $200 answering machine.

S: The telephone is definitely one of those things that has changed consistently over the years and you could, like, tell, like you can date a movie by the phones.

R: Oh yeah, absolutely.

S: Yeah, pretty well. Even, as well as you can, say, with computers, you know.

R: I've done that several times where I'm watching a film and, you know, sometimes a film will be set in a certain period but they don't come out and tell you right away...

E: Mm hm.

R: ...like a lot of indie films will do that, and I'm really just always looking for telephones so I can figure out exactly when it's supposed to be.

E: Within a few years accuracy, yeah.

News Items

Nvidia Debunks Moon Hoax (3:47)

S: Well, Jay, this is one the coolest things I think I've seen this week, or even for a while. It's a very interesting ad campaign by Nvidia, the graphics card maker. Tell us about it.

J: Yeah, it was very cool, Steve, I mean, I absolutely love that era of space exploration, you know, the 1960's/early 1970's, just the whole look of that series of missions the United State did. To me, it's like one of my favorite historical moments. I love World War II, I love space exploration in that decade, just awesome.

So, back in July 16, 1969, the Apollo 11 launched to the Moon. Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong were the lucky guys selected to land on the Moon and actually walk on the Moon. A lot of people think it was faked, and they make a lot of remarks about why it wasn't real, and this is some of the remarks that come out. So, a common claim is that no stars were visible in a lot of the pictures or all the pictures that were taken on the lunar surface. That the shadows on the Moon make no sense. Also, I heard that people believe that the way the astronauts actually move, the way that they jumped around on the lunar surface.

There's probably a couple of dozen points out there that people have brought up over several past decades, trying to refute the idea that we did or did not land on the Moon. The fact is, I'm going to break it to you know, that, yes, the United States did land on the Moon. It landed on the Moon more than once. There's artifacts on the Moon. By use of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, they've seen not only leftover space vehicles and other things, but they actually can see the footprints of the astronauts, like these long single-file footprints that the astronauts left as they were...

E: That's cool.

J: Yeah, isn't that awesome? You can see exactly where they went, because really, arguably, it hasn't changed really at all, because there's no weather or much activity happening on the Moon other than stuff flying in from outer space.

So, Nvdia created a new chip called the Maxwell, and the team that developed this, developed a way to show off this chip. They created a 3D software technology that allows them to bounce light off of all of the rendered objects much more accurately than anybody's ever done before. And this is one hell off an achievement because the processor power needed and the software needed is incredible, it's just, you know, something that hasn't really been achieved to this level of detail before. And I don't even think we've gotten even close to this level of detail before.

The engineers had to model every 3D object that they found on the Moon. So, that includes the spacecraft, the astronauts, the lunar soil, the rocks, any objects that were on the lander that were reflecting light. They were actually simulating detail down to what kind of materials were used to help simulate the actual effects of light bouncing off of it.

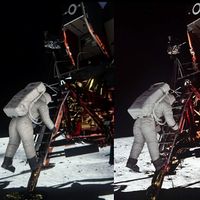

So, they selected a very popular picture of, now I believe that Neil Armstrong was already on the surface, and this was a picture of Buzz Aldrin getting out of the lunar lander, and Neil Armstrong was taking the picture. So, you see, it's a very iconic picture of an astronaut coming down the ladder right before they touched the ground. Now this was the picture that they decided to duplicate.

So, here's a little bit of their process. They had to figure out how the light actually reflects on the Moon differently than here on Earth. Now, one thing to keep in mind is that light doesn't simply just come in straight lines from the light source, say, in the room that you're in. If you look at the light source in your room, right, just turn my head and looked up at the light on the ceiling. You know, light, of course, is just coming in a perfectly straight line from that light source to me. But it's also hitting almost everything, if not everything, else that I'm sitting in the room with. And those objects are reflecting light to me and on other objects, which then again reflect light to me. Right, and it just keeps going, the amount of reflections, I bet, it would be interesting to do a calculation on just how many reflections are happening, how much of that light, how many times did it bounce before it actually gets to you.

And that gives a room, or a space, or any kind of area, a particular kind of illumination. And the illumination that a lot of people saw on the Moon in the photographs seemed very strange to them. But, there's a lot of significant differences between the Moon and the Earth. You know, in particular, the Moon does not have an atmosphere. And that does a very dramatic thing to the way that light looks on the moon. It looks a lot more stark, there isn't any diffusion happening, meaning that the light that's coming in through the Earth's atmosphere, it gets scattered, and it softens the light. And on a cloud-covered day, if you notice, if you take pictures outside on a cloud-covered day, you can get some of the best pictures outside because what's happening is all that sunlight is hitting the tops of the clouds and the clouds are diffusing the light a lot, and it makes everything look really soft. You can take very nice pictures without any harsh shadows on somebody's face and everything, it's very evenly lit.

The Moon is the exact opposite of that. The Moon, there is no evenly lit nothing on the Moon. You know, the vast majority of everything has a very, very bright light on it or it's almost completely in the dark. However, that being said, objects are bouncing a lot of that really harsh light very powerfully in all directions. So, when the team took into account, as they're trying to simulate this picture, all the different reflections and the different surfaces and the textures on those surfaces and how reflective are they and what direction are those different light rays going to be bouncing in, they did a simulation of the astronaut getting out of the lunar lander. And it looked good, but it didn't look exactly like what they expected, and they're like "Well, the astronaut isn't as lit up in this picture as we expected the astronaut to be to simulate the original picture" so they were saying that the astronaut just was dimmer than in the original picture.

So, they figured out they completely forgot to factor in the photographer, which I believe was Neil Armstrong, taking a picture of Buzz Aldrin. And when they put his space suit into the 3D rendering, bounced light off of it, there was so much light coming off of that space suit because of how reflective it was, and if you remember those guys were wearing almost stark white space suits, they were reflecting light like crazy. And the material that they were made out of as well was very reflective. They popped that space suit in there, and all of sudden, the picture looks almost identical, their 3D rendering looks almost identical to the original picture.

Take a look at the image guys, you can see it anywhere online, just look up "nvidia maxwell moon" or "nvidia moon", you'll be able to find lots of different images of this. And it's amazing how close that they got.

S: Now, Jay, just to point this one thing out. The Moon hoax conspiracy theorists have argued that in this very picture, because Buzz Aldrin is in the shadow of the lander, the he should be basically black, that you shouldn't be able to see him at all, because of the lack of diffusion, because they are not taking into consideration the interreflections. Especially the biggest one of which is Neil Armstrong himself who's just this bright light source shining back on Buzz Aldrin. So this completely blows that out of the water.

J: That's right, Steve. Neil Armstrong was actually standing far enough away from the lunar lander where he had direct sunlight hitting him, and he, in essence, was like a light reflector...

S: Yeah.

J: ... If you've done any kind of photography or film, you know, use a mylar reflector to bounce light. And he was that times five, because of the material and because of how large he is, he was like a huge flashlight lighting up Buzz Aldrin as he was coming down the ladder.

Yeah, so, another thing people are saying about this experiment that Nvidia did was it's yet another way of, in essence, debunking those lunar lander critics or the people that don't believe it, that don't believe we landed on the Moon. Because they couldn't have produced the lunar environment and they couldn't have taken pictures with that kind of lighting, they couldn't have simulated that in a studio. It just would not have been feasible for a lot of reasons and this experiment that was done by the Maxwell team at Nvidia proves it. So there's another example of how there was no way that they had the technology 40--50 years ago to fake the Moon landing.

S: Yeah, I mean, essentially, in 1969, they would have had to, if they shot this a studio, they would have had to simulate the lighting on the Moon in such a way that it would have withstood a recreation 45 years in the future with advanced graphics computer technology they could not possibly have anticipated would exist. If there were stage lights or anything else going on in here then the rendering, the Nvidia rendering wouldn't have worked.

E: Right.

S: It wouldn't have simulated...

E: It would have revealed something different.

S: Yeah, it would have shown something different.

J: So, in essence, what I'm saying is that we need to spend money to go back to the Moon.

S: Yeah.

(laughter)

E: Hear, hear.

S: We, I do also want to point out that they used their graphics card also to increase the exposure of the photos on the surface of the Moon.

J: Oh yeah, that was cool.

S: And the, so the other argument is "Why are there no stars in the sky?"

E: Oh, God.

B: Oh, God, that's the worst.

S: And the answer is 'cause it's daytime. You know, people think, "Oh, the sky's black. On Earth, the sky is black at night and so you should see the stars." But it's still daytime on the Moon when they're filming, and all that light is just washing out the stars, the stars are too dim. But, with their technology, they increased the exposure and, you know, so of course anything the lunar surface, anything on the lunar surface becomes total whiteout, but the black lunar sky, it becomes light enough where you can see the stars. The stars come out. So they are there. The stars are there in the background, you just can't see them because of the exposure.

B: Oh my God, so they're actually detectable to prove that they are there.

S: Yes.

B: That's epic.

E: (laughs) That's not going to convince any of the hoaxers, though, I mean, right?

R: Well, nothing's going to convince them.

E: They're not going to buy that.

J: No, I don't think so, Ev.

S: Yeah. Well, once you buy the conspiracy, then evidence becomes irrelevant, because the government, I wonder how much the government paid Nvidia to fake this, you know, to cover up their 45-year-old conspiracy.

E: Exactly, it just goes and goes and goes.

S: Yep. All right, thanks Jay.

GMO Feeding Trial (14:27)

Touch Pareidolia ()

Betavoltaics ()

Who's That Noisy ()

- Answer to last week: Rock exfoliation

Daniel Dennett ()

Science or Fiction ()

Item #1: There is more water in the Earth’s atmosphere than in all the world’s fresh water lakes. Item #2: All the water on Jupiter’s moon Europa is 2-3 times all the water on or near the surface of the Earth. Item #3: Scientists have discovered that water rain falls on large parts of Saturn’s upper atmosphere, originating from water in the rings.

Skeptical Quote of the Week ()

'If all your friends jumped off a bridge, would you jump too?' 'Oh jeez. Probably.' 'What!? Why!?' 'Because all my friends did. Think about it — which scenario is more likely: every single person I know, many of them levelheaded and afraid of heights, abruptly went crazy at exactly the same time… …or the bridge is on fire?' - Randall Munroe (xkcd)

S: The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe is produced by SGU Productions, dedicated to promoting science and critical thinking. For more information on this and other episodes, please visit our website at theskepticsguide.org, where you will find the show notes as well as links to our blogs, videos, online forum, and other content. You can send us feedback or questions to info@theskepticsguide.org. Also, please consider supporting the SGU by visiting the store page on our website, where you will find merchandise, premium content, and subscription information. Our listeners are what make SGU possible.

References

|