SGU Episode 40: Difference between revisions

Jim Gibson (talk | contribs) m Mark as being transcribed. |

Jim Gibson (talk | contribs) Complete transcription. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Editing required | {{Editing required | ||

|proof-reading = y | |||

|formatting = y | |formatting = y | ||

|links = y | |links = y | ||

| Line 24: | Line 19: | ||

|forumLink = http://sguforums.com/index.php/topic,52.0.html | |forumLink = http://sguforums.com/index.php/topic,52.0.html | ||

|}} | |}} | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ''You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.'' | ||

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, April 26, 2006. This is your host, Stephen Novella, President of the New England Skeptical Society. With me tonight are Rebecca Watson ... | |||

R: Hello. | |||

S: ... Perry DeAngelis, ... | |||

P: Good evening, everyone. | |||

S: ... Jay Novella, ... | |||

J: Good evening. | |||

S: ... and just returning from a trip to Las Vegas, Evan Bernstein. | |||

E: And boy are my arms tired. | |||

P: Oh, oh, man! | |||

R: That's the best you could do? | |||

J: That's how we're starting the show? On a low note, Evan? | |||

R: That's terrible. | |||

E: I've traveled twelve hours today. I was up at 6:30. I'm just getting now to my computer at home. | |||

R: That's no excuse. | |||

E: So cut me a little bit of slack. | |||

P: How was your trip to Sin City, Evan? | |||

E: It was very, very good. It was productive. | |||

P: Excellent. | |||

R: Productive? Hm. | |||

E: It was productive. | |||

J: Did you gamble at all? | |||

E: I did gamble. | |||

J: What did you play? What's your game? | |||

E: Well, I played a little bit of craps and won $25, and then I stuck fifty cents in a slot machine and won $1300. I hit a jackpot. | |||

P: Is that true? | |||

R: Are you serious. | |||

E: Yup, it's absolutely true. | |||

P: Wow! | |||

J: Oh, my God! | |||

R: There you go. That's fantastic! | |||

S: Congratulations. | |||

E: Thank you. | |||

R: Slot machines are great. | |||

J: Do you know what's so funny? Bob, who is absent tonight, was on a cruise last week, and Bob won $1000 playing blackjack. | |||

R: Wow. | |||

E: Sweet. | |||

J: I'm going to go gamble soon. | |||

S: Yeah, there's got to be some sort of skeptical sign in a favorable part of the heavens or something. | |||

P: That's right. | |||

E: Absolutely. | |||

R: Totally. | |||

S: Bob is not with us tonight. He is at a physics conference that he will report to us on next week in the next episode. | |||

R: Oh, oh!. I washed a pair of pants, and I found a $20 bill balled up in the pocket when I took them out. | |||

J: That's amazing! | |||

E: Well, we're all just making money left and right. This is incredible. | |||

J: I can't take this. | |||

R: Yes. | |||

S: Now I'm looking through the latest issue of ''The Skeptical Inquirer'', a must-read, by the way, for any self-respecting skeptic. | |||

P: Fine publication. | |||

S: Fine publication. And I see here on page 11 a picture that is captioned ''Skeptical youth at the conference'', and this is talking about James Randi's Amazing Meeting, which was in Las Vegas in I believe it was in January, including our very own Rebecca Watson. | |||

R: Oh my God! Really? I actually didn't even know that. | |||

S: You didn't see that, yet? There she is in all her glory. | |||

R: No. | |||

S: You were one of the "skeptical youth" at the Amazing Meeting. | |||

R: I don't think I'm a youth any more. Am I? | |||

E: Well, compared to skeptics out there you most certainly are. | |||

R: I'm 25. I guess it's relative. | |||

P: Did you seem youthful at the meeting? Did you look around yourself? | |||

R: I think I was rather youthful, yeah. That's true. | |||

P: There you go. | |||

R: Is it a good picture, because I haven't seen that? | |||

S: It's you and a few other guys: Dave Hawley, Matt Fiori. Do you know these guys? | |||

R: Yeah, yeah. Wait. What are you suggesting? That I'm hanging out in Vegas with a bunch of guys and I don't even know who they are? | |||

S: Well, there's the picture. | |||

R: Uh, uh. Yeah, thanks, Steve. | |||

P: We have photographic evidence. | |||

R: Thank you for besmirching my character on the podcast, Steve. | |||

S: You're welcome. Anytime. | |||

=== Rebecca's Biblical Challenge Follow Up <small>(3:12)</small>=== | |||

S: Now, Rebecca, just a quick follow up. On a previous podcast, I issued you a specific challenge: to find a reference in the Old Testament to Mothra, although I did widen it a bit to allow you some leeway. It could be any Japanese monster, movie-monster: Gamera, Mothra, take your pick. | |||

R: Right. | |||

S: This was spawned by the notion that some literalists, creationists interpret some Old Testament passages about behemoths and leviathans to mean references to dinosaurs, even specific dinosaurs, and you said you could find a passage that you could twist into a reference for Mothra. So, were you successful in your attempt? | |||

R: I did even better. I found one in the New Testament, ... | |||

S: Okay. | |||

R: ... which is so much better than the Old Testament, because, you know, it's newer. But in Matthew -- it's true -- Matthew 6:19 says "Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth where moth and rust destroy." Now, I know I don't have to explain this to you guys, but just to spell it out for our slower listeners: Japan represents the overabundance of wealth, the treasures on Earth that are being stored up. The rust obviously represents the red-winged monster Rodan. | |||

S: Okay. | |||

R: And then, of course, there's the moth "Mothra." QED. | |||

P: Very excellent. | |||

S: Okay, not bad, not bad. | |||

P: Excellent. | |||

R: Not bad? That's perfect. That's right on. | |||

S: Pretty good. | |||

J: I don't know. | |||

== News Items == | == News Items == | ||

=== Sonoma Bigfoot Revealed <small>(4:45)</small>=== | === Sonoma Bigfoot Revealed <small>(4:45)</small>=== | ||

S: Now, speaking of Las Vegas, which brings us to Penn and Teller. Penn and Teller have the wonderful show on Showtime called ''Bullshit'', where they poke relentless fun at the most ridiculous stuff that they can come up with, which is not challenging. They have an upcoming episode where they are discussing cryptozoology, including ... | |||

R: Actually, I think it just aired. | |||

S: Did it just air? | |||

R: I think it aired two days ago. | |||

S: Well, on the website, they had a little preview of the show. Did you see the whole episode, Rebecca? | |||

R: I haven't seen it yet, no. | |||

S: So the preview shows footage of Bigfoot, footage which is known as the Sonoma Bigfoot, because of its alleged to have been filmed in Sonoma, California. And this was filmed in November of 2005, and on their show, on the show ''Bullshit'', Penn and Teller are admitting that they hoaxed the Bigfoot footage. | |||

R: Yeah, it's really awesome, because they released this footage back in November, and a lot of Bigfoot enthusiasts really grabbed ahold of it. Like the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization, BFRO. | |||

S: Yeah, they took the biggest hit. | |||

R: Yeah. Because they're like ''the'' big Bigfoot organization, I guess, and on their website they grabbed ahold of this stuff, and they said things like "we've seen hoax footage over the years, but there's no way that this could of been hoaxed. It's definitely not a man in a costume." Like, just open up your mouth wide and insert one big foot, because ... | |||

S: Yeah, open mouth and insert big foot. They mentioned specifically about anatomical details: the length of the arms, the nature of the walk, a lot of the kind of things that's familiar with other Bigfoot video analysis. | |||

R: Right. | |||

S: And of course, they were proving, basically, that they ''cannot'' distinguish a hoax from what is real. | |||

R: Exactly. | |||

S: Although, to be fair, I searched as extensively as I could online, on the Sonoma Bigfoot, and there are quite a number of Bigfoot sites that thought it was a hoax. | |||

R: Right, right. | |||

S: So they didn't take in everybody. Certainly, the ones who were taken in, that's a huge hit to their credibility, which I suppose is the whole point of the hoax to begin with. | |||

R: Oh, yeah. And if you watch the video, it's so obvious they didn't even try. It's so badly done. | |||

S: Yeah, I think they tried to do it so badly, that that would make it all the worse, that somebody would believe it. | |||

R: Yeah. | |||

S: But I think they might've gone a little bit too far. I'm sure that they'll play up on their episode, the one's who bought it hook, line, and sinker. But it does backfire a little bit in that the pro-Bigfoot sites that were critical of it, can say "Ah, we knew that was a hoax," so that ups their street cred, basically. | |||

R: Right. | |||

S: It kind of had mixed results, and I think that if you're going to do something like that, and not that we haven't talked about it. That's kind of the fantasy of all skeptics is to pull the big hoax, right? But it is very difficult. If you're going to do it, you have to make sure you fool everybody. Otherwise, it does backfire on you. The other potential downside to it is that you have to make sure that you so carefully and fully document your hoaxing that nobody can claim afterwords that you're lying about having hoaxed it. That it's actually ... | |||

R: Which is exactly what they're doing right now. | |||

S: Which some people are now still doing. They think it's still real. This all goes back to — the first person to do this was James Randi. | |||

E: Oh, yeah? | |||

S: Project Alpha. | |||

R: Yeah | |||

S: Are you guys familiar with this÷ | |||

E: Yeah. | |||

R: Oh, yeah. | |||

J: Yes. Excellent. | |||

S: Where Randi planted a couple of mentalists, magicians, in a psychic researcher's lab, and through sleight-of-hand, bending spoons, mostly, they completely had these guys going. They had them completely hoodwinked as well as a large portion of the psychic research world, until Randy revealed the whole thing to be a trick. Those who bought into it — same story — those who bought into it, their credibility was severely hurt, and there even many research programs that were shut down because of that loss of credibility. So it had the intended effect, although it had other reverberations. For example, striking a wedge between the skeptical scientific community and the psi research community. It significantly contributed to their isolation from the rest of the scientific world, which I don't know if that's a good thing or a bad thing. | |||

J: Steve, do you remember when you had the Bigfoot program not too long ago and you interviewed someone ... | |||

S: From the Pennsylvania Bigfoot Society. | |||

J: Right. I remember you saying — I was listening to that episode not too long ago, and I remember you saying that in a lot of these — the footage that people see, there's that particular gray area where the quality of the film is at a certain level, the distance from the subject is at a certain level, and I noticed that in the Penn and Teller video that they really did do what you described in that video. They had the distance and the blurriness and the unsteadiness of the camera. | |||

S: Right, yeah. It was enough to be provocative, but not in sufficient detail to be definitive. | |||

R: Right. And Steve, I just wanted to pop back to what you were saying before, really quickly, about how a lot of people are now saying that Penn and Teller are faking, that they were faking it. | |||

S: Right. | |||

R: And how important it is to document how you're faking it, but I just have to say that so often it doesn't really matter. There will always be those true believers ... | |||

S: Right. | |||

R: ... who are going to say "No, it's real." I've given people cold readings where I've told them afterward "that was a fake, and here's exactly how I did it," and they'll say "no, no, you really have psychic powers, you just don't know it." | |||

P: You just don't know your own power. | |||

R: Yeah. | |||

S: That always happens. | |||

P: Yup. | |||

S: But at least with like a video of a Bigfoot, you can have another camera taping the hoaxing. | |||

R: Right. | |||

S: You can have some concrete evidence to show the process of doing it. | |||

R: They do end up showing the guy who played Bigfoot in the video, and they have him reading the emails that they got as a result of it on that episode of ''Bullshit''. They do show the suit and how they made it and (''unintelligible''). | |||

S: It's entertaining. It's at the level of the show. I mean I love the show; I think it's great, but they definitely err more on the side of entertainment. | |||

R: Oh, yeah, definitely. They've never said that they're doing anything like science. They're just having fun. | |||

S: No, no. | |||

E: We've all seen how the crop circles are made, and that's obvious. | |||

R: Oh, yeah. | |||

E: It's very easy to document that hoax. | |||

R: Right. | |||

S: That's been done. People have documented themselves hoaxing crop circles ... | |||

E: Oh, yeah. | |||

S: ... that were later pronounced genuine by the crop circle community. | |||

R: Oh, some of the most complex things. | |||

E: You don't have to hide a camera, or anything. You just tape doing it, and then you bring out the the crop circle believers the next day, and they're all over it, and you show them the tape back here — "we did it." | |||

P: I believe you're referring to cereologists. | |||

S: Cereologists. | |||

E: Yeah, right. | |||

P: That's what they call themselves. | |||

S: As they like to refer to themselves ... | |||

P: That's right. | |||

E: Scienticians. | |||

S: ... in classic pseudo-scientific fashion. | |||

E: Oh, my. | |||

P: Cereologists! | |||

S: Evan, when you were in Las Vegas, did you see Penn and Teller? | |||

E: I did, in fact, yes. At the Rio. They do a show every night except Tuesdays. They're dark on Tuesdays. An excellent show, outstanding. Two things of note: the first thing was before the show, they invite everyone up on stage to inspect a wooden box that's on a set of castor wheels, and you can do whatever you want. You can touch it; you can move it. It's a box, and, obviously, you know, a person would fit inside this box, and everyone went up there, inspected that box, and to start the show, the piano player says "okay, here they are — Penn and Teller. Penn comes walking out one side of the stage, goes over to the box, taps on it, and out pops Teller, out of nowhere. It's just really incredible. It really got the show off to quite a bang, and everyone was just in stitches laughing, and everyone was — nobody saw how Teller got in that box. That was pretty ... | |||

J: Evan, was is it possible that he was in there the whole time? | |||

E: No. Absolutely not. He snuck in somehow. | |||

P: Do you think it was a miracle? | |||

E: Yes, absolutely. | |||

S: You don't think it was some sort of trick? | |||

E: It was a perfect deception. | |||

P: Come on, Steve, Occam's razor: a miracle, a trick, I think trick gets cut off first. | |||

E: What was even more impressive ... | |||

S: It is the more complicated explanation. | |||

E: The other thing I thought that was even more impressive is that they had a stack of five books, joke books, and according to Penn these are the top five joke books off of amazon.com. He hands them to a member of the audience, all right, tells the person "choose a book," all right, choose any one of those five, and then hand it to the person in back of you. And then that person hands it back of them, and it works its way through about eight sets of hands, somewhere to the back of the room. The person then opens the book anywhere. Penn doesn't know which book you're looking at. He opens the book, you choose a joke, and Penn is able to "psychically" come up with the punchline for the joke that you are thinking about. It's a wonderful cold reading trick that he does, and he did it to perfection. It was very, very impressive. | |||

P: That's awesome. | |||

: How was the joke? | |||

E: I don't recall. It was something about the difference between a millionaire and a billionaire. I don't even remember what the punchline was. | |||

S: I don't know how they do it, but it probably wasn't cold reading. They were cheating. He had some way of knowing what joke they were looking at. | |||

E: Well, he explained in the context. This is in effect what the cold readers do. He says they don't even do it half this good. | |||

S: No, they don't. | |||

E: That he can do it, and if he's telling you that it's a trick, then everyone — he wants to make sure every one in that audience knows that psychics are absolute BS. | |||

S: Right. The best of the cold readers are mentalists. The psychics who do cold reading, whether they know that's what they're doing or not, are not that good at it. Like John Edwards really is not that good at cold reading. | |||

R: Right. He's terrible. | |||

P: That's why he's not on TV anymore. | |||

E: He's horrible. | |||

R: He is on TV. He's on Women's Entertainment, because that's what entertains women. Women's Entertainment — WE TV. | |||

P: Seriously. I did not know that. | |||

R: Swear to God. | |||

P: Well, he's not on NBC anymore. | |||

S: If I were a woman I'd be insulted. | |||

R: Oh, yeah. And plenty women are. | |||

J: Is John Edwards a faker, or do you think he is a self-deceiver? | |||

R: He's a faker. He's a fraud. | |||

E: He's a faker. | |||

R: I know you weren't asking me, but that's just fact. He's a fraud. And he knows it. | |||

P: He's also the biggest douchebag in the Universe. | |||

R: He is. | |||

S: I was trying to think of a way to say it a little more diplomatically, but the bottom line is, when you can see him using cold reading techniques consciously, statistically, he's got to be deliberately faking it. Do you know what I mean? | |||

P: Of course. | |||

S: You can't be deceiving yourself when you're using conscious deceptive techniques. | |||

P: He's a con artist. That's the official stance of the New England Skeptical Society. | |||

S: Right. In our opinion. He's a con artist. | |||

P: You told us off-air that you spoke to them briefly, Evan? | |||

E: Yeah, well what they do is after the show, they go out into the lobby, and you can have your picture taken with them. They'll sign autographs, and they'll talk to you for a little while. So, I did get a chance to speak with both of them, and although nothing official, I did invite them onto our show, so that we could interview either of them or both of them, and they said that they would seriously consider it. | |||

S: Their people will talk to our people. | |||

E: Exactly. | |||

S: Great. | |||

E: I did speak to one of their PR people as well. They all have our business card, and I'm hoping to hear from them in the near future so that we can make an arrangements and have them on this podcast for you. | |||

S: I would love to have them on the show. | |||

R: Can I also — can I just mention that the bullet catch that they perform that was designed by Banacek, who is another really amazing magician that people should check out if they've never heard of him. He's a great mentalist. Yeah, he's amazing. | |||

E: I didn't know that. | |||

=== Channeling John Lennon <small>(16:33)</small>=== | === Channeling John Lennon <small>(16:33)</small>=== | ||

S: Let's go on to our next news item this week: "TV Seance Claims to Have Reached John Lennon." So in a brazen attempt to exploit the memory of John Lennon, a pay-TV service in-demand aired, I believe, on Monday — I didn't pay the 10 bucks to see it ... | |||

R: Aw. | |||

S: ... aired a live séance in which they purport to speak to the ghost of John Lennon. | |||

P: Did he sing? | |||

S: I don't suppose any of you caught this? | |||

P: No. | |||

R: No. | |||

E: No, I didn't. | |||

S: They had on their EVP, which stands for electronic voice phenomena, specialist Sandra Bellinger to examine the voice, and she proclaims "It's the real deal. That's very consistent with a class A EVP" -- that's good pseudo-scientific jargon, there -- she said regarding the level and clarity of the voice. She also says the voice sounds like how Lennon would have talked. | |||

R: If he were dead. | |||

S: If you were dead, I guess. What a surprise. | |||

R: And who's going to disagree with here, seriously. | |||

J: Steve, were they like listening to it and like "Is that you, John Lennon?" "Yes, it's me." Are you kidding me? | |||

P: It's so stupid. | |||

S: It's lame. This is the same people a couple years ago in 2003 that attempted to contact Princess Diana through channeling. | |||

P: Did that one work? | |||

S: No. | |||

P: No. | |||

S: So they're making a (''unintelligible'') | |||

E: So that's called English channel. | |||

J: What did John Lennon have to say? | |||

S: You know, because I don't want to discourage people from paying the 10 bucks, they were not releasing any specifically what he said during the alleged séance. | |||

E: Did they mention if they informed Yoko Ono of this or if she had any comment? | |||

S: Yoko One, to her credit, declined to comment. | |||

E: Good. | |||

S: And their long-term spokesman said that this was an exercise in tacky, exploitative, and far removed from the icon's way of life. | |||

P: Thank you. | |||

S: So Lennon's people were pretty condemning of the whole affair. | |||

J: I can't help but think, like, let's suppose together that okay this really does exist, right? What's going on on the other side? If you're the ghost of John Lennon, we'd hope that he's in heaven, right? Ghosts exist and let's say heaven exists. | |||

R: Well, just imagine there's no heaven. | |||

J: Is he straining on the other side to communicate? Like was he hearing them in the same ridiculous manner that we're hearing him? As blurry and fuzzy to him? Is he waving his arms? What's going on? | |||

S: I always thought they were playing charades. "I see an M. Is it an M?" | |||

P: I imagine mostly what he does is think of ways to haunt David Chapman. I imagine that is what he probably spends most of his time doing, I'm guessing here. | |||

== Questions and Emails <small>(19:26)</small>== | == Questions and Emails <small>(19:26)</small>== | ||

S: We do have a large number of emails, which keep coming in, and which is great. We appreciate all the emails that you send us. I'm going to read a select few. I'm going to start with actually three emails, all of which provide either some small correction or addition to one of our recent podcasts. Now one of the great things about doing a show like this and as our community of listeners is growing, there's always somebody out there who knows probably more about a specific topic that we do. Especially when we stray from the things that we've really researched and we're talking a little bit more off-the-cuff. There's always one layer more of detail or accuracy or precision that you can get to. So, and it's great to get that level of clarity and detail into our shows. So definitely send us those corrections and additions. However, we are definitely getting to the point where we can't read them all on air. We are working, especially Jay, our webmaster, is working on developing our bulletin board, and either through that or something similar, we're going to provide a location on our website where listeners can not only discuss our shows, they can also add their links and references, and maybe make some additions or corrections as necessary, and we'll talk about the ones that are especially important or interesting on-air. But I'm going to mention a few that we did get over the last couple of weeks. | |||

=== Hurricanes <small>(20:49)</small>=== | === Hurricanes <small>(20:49)</small>=== | ||

S: The first one is about the global warming and hurricanes. This email is from Keith, who says | |||

<blockquote> | |||

Hi, guys. In your latest podcast you were discussing the impact of global warming on hurricanes. Steve and Perry stated that statistically we would have more storms, hurricanes with global warming. I think the current research says that we would have more intense hurricanes, but we have no evidence of more frequent hurricanes. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Then he gives a reference, which we have on our website. He says: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I know this is a minor point, but you guys always seem concerned with being accurate, which I appreciate. | |||

Avid fan, Keith | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Again, thanks Keith for writing us, and I did check this out. I try to do as much background research as I can. The key reference is on pewclimate.org, and that's basically correct. The current evidence shows that increasing ocean temperatures, whether you think it's due to man-made global warming or not, increases, definitely increase the intensity of hurricanes. However, so far, there's no evidence that it increases the number of hurricanes. The number of hurricanes recently has, in fact, been increasing, but it fits into the pattern of waxing and waning number of hurricanes over the last hundred years. So, again, we get to that same sort of controversy of: is the recent increase a trend or just part of the normal oscillation. It doesn't really change the essence of what we were talking about, but it's a good example of how there's always that extra layer of detail to get to. | |||

=== Birthday Problem <small>(22:17)</small>=== | === Birthday Problem <small>(22:17)</small>=== | ||

S: The second correction comes from Mike Chartier (or chart-ee-er), who writes | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I would like to correct your birthday problem posed in the first part of the latest show. First off, the problem should be stated ending with at least 50 and not a 50-50 as you stated. The correct answer to the problem is 23, not 20. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Basically, this is the ''birthday problem'', where, again, this was sort of an off-the-cuff comment. How many people would you have to have in the same room in order to have a greater than 50% chance that two of them have the same birthday? And I recalled that as being 20, although Evan, you say that you said 23. | |||

E: Yeah, and I did, and you know what, Steve? I do have it on that tape. I happened to record that lecture we did years and years ago ... | |||

S: Right. | |||

E: ... at Southern Connecticut State University, and at that lecture we presented the number being 23. | |||

S: Yeah, I had stated off of memory as 20, but 23 is the accurate number. That's when it gets a little bit over 50%. | |||

=== Evolution Books <small>(23:13)</small>=== | === Evolution Books <small>(23:13)</small>=== | ||

S: The third correction — this is actually more of an addition. This one comes from Roy Peterson in the UK. Roy writes: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I have just downloaded your latest podcast, which was recommended via the Skepticality Forum. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

That's interesting. | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I was flabbergasted that your recommendations ... | |||

</blockquote> | |||

R: I think that was me, actually. | |||

S: Oh, thank you. | |||

E: We have a mole. | |||

R: I was pretty upfront about it. | |||

S: Well, good work. | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I flabbergasted that your recommendations to a listener's voice request for more information on evolution did not include one of Richard Dawkins books. What about ''The Selfish Gene'' or ''The Blind Watchmaker''? These are classic publications on the subject. You naughty people. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

and he sent that with a little frowny-face. | |||

R: I love when our listeners call us naughty. | |||

S: Sometimes we are very naughty. Well, Roy, I definitely appreciate your recommendations. We'll add them to our list on that notes page. ''The Selfish Gene'' and ''The Blind Watchmaker'' are absolute classics in evolutionary writing. And this was not deliberate on my part. It just happened to be the books I had on my shelf that I was looking at. Richard Dawkins and, really, that was at one end of the spectrum in terms of some controversies of modern evolutionary thinking, and Gould and Eldridge are at the other end of the spectrum. So the two books, ''The Selfish Gene'' and ''The Blind Watchmaker'', are important, not just for completeness, but also to provide good balance to Gould's take on modern evolutionary theory. Which is a very interesting topic. We don't really have time to get into it completly here. It has a lot to do with the inherent progressiveness of evolution, and can you understand evolutionary theory at the gene level, or do you really have to look at it at multiple levels: gene versus species versus populations and even ecosystems. Very, very interesting details about the way evolution progresses and the way natural selection works and operates. So, I accept those additions to our recommended evolutionary reading. | |||

=== Bananas and Logical Fallacies <small>(25:19)</small>=== | === Bananas and Logical Fallacies <small>(25:19)</small>=== | ||

== Interview with Brian Trent <small>(35: | S: The next email: it's about logical fallacies. This one comes from Mark Smith in Lansing, Kansas. He says | ||

<blockquote> | |||

My only suggestion ... | |||

</blockquote> | |||

I'm sorry, he starts out writing about Dianetics, and basically just telling us how ridiculous it is. He says: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

I'm still laughing years later at how ludicrous Dianetics is. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

and then he goes into a question. He says: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

My only suggestion for the show would be to put more of an emphasis on logical fallacies like the ones listed on your webpage. Logic geek that I am, I find these very entertaining, and they're also useful everyday tools, especially in a popular culture where fallacious thinking runs rampant. But they're not always self-evident, even when they have been pointed out and identified. As a result, I think the nature of fallacies is too often ignored. For instance, I happen to have on my desk a booklet called ''The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools'' from the Foundation for Critical Thinking, and, amazingly, I can find no mention of logical fallacies anywhere in it. One idea for the show would be to spotlight a fallacy and explain it using current examples from popular media or the news. The examples wouldn't need to be from scientifically-oriented stories exclusively, as long as they include an attempt to support a certain position using a logical fallacy. I have a feeling that examples would be trivially easy to find. Thanks for the great podcast. In a perfect world, you guys would be paid like pro basketball players, and Rebecca would be on the cover of every magazine. Keep up the fight and keep living the sweet dream of reason. Woo-hoo! | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Well, Mark, thanks for the kudos. | |||

R: That's definitely the best letter, yet. | |||

S: That was the best ending to an email that we've had recently. That's not the first person to suggest that we should be making lots of cash doing what we're doing. I have the feeling that we're missing something. Maybe we're not as smart as we think we are. | |||

E: Yeah, if there's a promoter out there who wants to work with us, I'm sure we'd be open to speaking with him. | |||

P: I'd be willing to shoot a few hoops. | |||

S: Well, Mark, we like your idea about showcasing logical fallacies. We have bandied that idea about in the past, and I do think it is time that we add a logical fallacy segment. So we're going to try out a couple of formats before we solidify something, at which point we might have even some intro music, but we're going to do a brief logical fallacy segment on this show. By coincidence, unless you are the kind of person who doesn't believe in coincidences ... | |||

R: At which point, go away. | |||

S: ... we had another email this week. This one comes from Cecil in Chicago, Illinois. And Cecil writes: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

Here is a short clip of Kirk Cameron visiting with a guy who tries to prove the existence of God by exhibiting the amazing design of the banana. I checked the top 20, and I am not skilled enough to recognize a logical fallacy. Can you help? | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Well, this is a perfect opportunity to play our new game, which is ''Name That Logical Fallacy''. But, first, Rebecca, you specifically asked if you could give a synopsis of the banana argument. | |||

R: Yeah. | |||

S: The God of the Bananas is what I'm calling it. So give us the synopsis. | |||

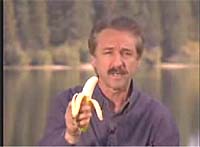

R: I love this clip. For those of you who don't know, it's got Kirk Cameron of Growing Pains fame and some Australian dude sitting by a lake talking about silly atheists are. And at this particular part, he says, the Australian guy says "behold the atheist nightmare," and he pulls out a banana. | |||

S: I recoiled when I saw it. | |||

R: We all did, a little. The banana, you know, it's a banana. It's about seven inches long, an inch-and-a-half thick, or so. You know, your average banana. And he says "Now, if you have a well-made banana, you'll find on the far side there are three ridges, and on the near side, two ridges, ridges apparently being very important. And then he goes on to compare that shape with the shape of a human hand when holding the banana, and saying that they're a perfect fit. He says the banana and the hand are perfectly made, one for the other, at which point he slips the banana suggestively into his hand. He says "you'll notice that the maker of the banana, or mighty God, has made it with a nonslip surface -- another very important trait, apparently. He then goes on to say "God has placed the tab at the top. When you pull the tab, the contents don't squirt in your face." I'm not making this up. That's word-for-word. | |||

S: We have the link for the video clip. It is (''unintelligible'') | |||

R: He says when you pull the tab the contents don't squirt in your face, which is true, so long as you aim it away from you. | |||

S: Even if you shake the banana, they don't squirt in your face. | |||

R: You can do whatever you want to the banana, it will never squirt you in the face. | |||

S: And I've tried. | |||

R: And then my favorite quote: he says "the wrapper has perforations. Notice how gracefully it sits over the human hand. Notice it has a point at the top for ease of entry. Just the right shape for the human mouth, and it's even curved toward the face to make the whole process easier. | |||

P: Now, wait a minute. | |||

R: Just to remind everybody, yeah, we're talking about a banana. | |||

P: This is a joke video, right? | |||

R: No. | |||

S: This guy is dead serious. | |||

R: This is dead serious, and he seems to believe that he's still talking about a banana by the end of that. Read from that what you will. | |||

P: Oh, God! | |||

S: Well, as Freud said, sometimes a banana is just a banana. Well, let's talk about the logical fallacies inherent in this argument. They are subtle, and I immediately teased out three logical fallacies. We'll see, maybe we could find more. I think the core logical fallacy is a tautology, mainly that the argument is because the banana is convenient for humans to eat that that convenience is what caused the banana to be the way it is. In other words, it was therefore specifically designed to be convenient for humans to eat, or the effect causing the cause. That's the core logical fallacy. But you have to couple the tautology with an unstated major premise behind the entire argument, which is that design implies God. That because the banana is designed to be convenient for eating, that God is the only thing that could have done that, and he is dismissing without specifically saying so, hence an unstated major premise, that evolution could not have resulted in a fruit that has features that make it convenient for human consumption. In fact, fruit evolved to be convenient for animal consumption. That's the purpose, evolutionary purpose of fruit. Animals will eat it. | |||

R: And not only that, Steve, but haven't humans genetically modified bananas to be ... | |||

E: Yeah, isn't this a case of artificial selection? | |||

S: In addition, thre has been some — I don't think it's been genetically modified, it's was just through breeding. | |||

R: Ah, right. | |||

S: A lot of the things, a lot of the crops that we use have been modified through human tinkering. So, to be even more useful for human consumption than the nature made it. | |||

R: Right. | |||

J: Rebecca, did this guy think he was conducting science? | |||

R: I think he did. They seemed to think that this is like logical. They seem to believe that this is the death knell for atheism. | |||

P: I know it's not appropriate in our constant search for and endeavor at erudition on this program, but can't we simply say that this is asinine? I mean is it appropriate in this case? It beggars the imagination. | |||

R: Then we can't have fun dissecting his fallacies. And I really like dissecting his fallacies and saying that when we're talking about the bananas. | |||

S: Yes, that is certainly more apropriate in this case. | |||

J: The guy is a total pervert. He's a pervert. "I like the way the banana feels in my mouth." | |||

(''laughter'') | |||

S: Sometimes things are so absurd. | |||

P: Sometimes our initial reaction is that this is asinine! | |||

S: The initial reaction that it is asinine or absurd is appropriate and accurate. But, part of doing this show is to go beyond that. Let's take it the next step. And let's take great pains to explain exactly why it's absurd. The reason is that when you have these really extreme examples of logical fallacies, they make good examples to teach you how to avoid more subtle logical fallacies in claims that are not initially obviously absurd. | |||

J: What about all the fruits that exist that aren't easy to eat. | |||

S: Now, Jay, that brings up the third logical fallacy that I teased from this, which is the fallacy of inconsistency. If you're going to say that the convenience, the easy digestibility of the banana is evidence of a benign Creator, then you have to argue that everything in nature which is inconvenient and harmful is contradictory evidence or evidence against a benign Creator. | |||

P: It's evidence of Satan. | |||

R: The lobster is evidence that God hates us. | |||

S: The lobster, or have you ever tried to eat a pomegranate? | |||

J: Not going to happen. | |||

P: Or an artichoke? It might have choked Artie, but it ain't going to choke me. | |||

E: I ate six seeds of a pomegranate once. | |||

S: But, guys, don't miss the whole point of ''Name That Logical Fallacy''. Maybe in the future I might have to challenge you guys to see if you could come up with the logical fallacies. | |||

R: Yeah, I like this idea. I enjoy this. | |||

S: It is fun. | |||

== Interview with Brian Trent <small>(35:23)</small> == | |||

Author of ''Remembering Hypatia'' | Author of ''Remembering Hypatia'' | ||

S: Well, we have a interview this week, an interview with Brian Trent, and let's go to that interview now. | |||

S: Joining us now is Brian Trent. Brian, welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. | |||

BT: Thank you for having me. | |||

S: Brian is the author of the award-winning historical novel ''Remembering Hypatia'', which is about the final collapse of enlightenment of the ancient world. He's also the author of numerous books and articles on topics as diverse as future immortality and the effect of modern technology on privacy and freedom. So, Brian, why don't we start by you telling us — just give us a synopsis of ''Remembering Hypatia'', and just thematically what is this book about? | |||

BT: Certainly. Well, the story takes place in the final days of not only the great library of Alexandria, one of the greatest repositories of learning in the ancient world, but also the last 23 days of the life of Hypatia, who was the last curator of that library. She was a mathematician and astronomer, a philosopher, and a teacher at a time when women were pretty shunned from learning to begin with. And she pretty much achieved the Renaissance man ideal, about a thousand years before it was fashionable. She was one of the most brilliant people in history. She was murdered, the eve of the dark ages, by a man who was later proclaimed to be a saint. Her death, her assisination, is one of ''the'' pivotal events. It pretty much closes off that era of history, the classical age of history, and we have then the medievalism that characterized the dark ages. | |||

S: Now, do you think that her death was just a milestone marking an inevitable transition, or do you think that her death actually contributed to or hastened the dark ages? | |||

BT: Well, she lived in a time when there was a — there was an upswing of religious fundamentalism, and, again, this is not about religious freedom. I mean Alexandria, where she lived, was a place that had rampant religious freedom. Earl Robinson described America one time and said that "all races and religions; that's America to me." Well, that same sentiment applies to Alexandria. It was a pluralistic community. It was a multicultural community, and there were, even with Christianity itself, there were different sects of Christianity, which would debate with each other and philosophize about the nature of divinity and the trinity and so forth. Well, there was a hardline faction, which was taking control of the city by force. Mostly through the force of personality of Archbishop Cyril, the guy would later have her murdered, and she stood against them very strongly, very publicly, and her death, I think — I think her death was a knock-out blow in that title fight. It showed people that if you stand up against the guy, you're going to get murdered, because nothing was done about it, and really no secular authority ever challenged that theocratic regime again. | |||

S: So, her death had a chilling affect on anyone else who would stand against the authority of the Archbishop. | |||

G: That's fair to say, and you have -- the next thousand years were characterized by that very hard-line, fundamentalist elements, at least until the first glimmers of the Italian Renaissance. So, it was a shift into an era of witch burnings and crusades, where knowledge was limited, first of all, and knowledge which disagreed with the prevailing theological notion of the universe was destroyed, for the most part. And at other times, it was just buried or sometimes literally painted in between — some monks in monasteries would fold papers of Archimedes in half and put new papers over it to make it nice and sturdy for their illuminated manuscripts. That's the kind of era that we saw for the next thousand years. | |||

P: What year was her murder, Brian? | |||

BT: It was in the fifth century, around 414 or 415 AD. | |||

P: And how long was the library in existence? | |||

BT: The library had been formed probably around nine years after Alexander The Great's death. When he created the city of Alexandria, quite literally, he drew it in the dirt, and it was after he died, it was built, probably around nine years later. So we're talking about a 700-year-old learning institution. | |||

S: And because Alexandria was such a well-traveled city and so cosmopolitan, pretty much every ship that came through its port, its manuscripts and whatever books it may have happened to have on board were copied and stored in the library of Alexandria. So it was an absolutely incredible repository of ancient writings and literature and knowledge. What a loss to history the destruction of that library was. | |||

J: Do we have an idea of what some of those books might of been? Like how advanced were their mathematics and their cosmology and things of that nature? | |||

BT: Well, certainly, we have some tantalizing glimpses. We have, for example, most school children today are taught that it was Columbus and Magellan who pretty much determined that the world was round, and this and that. But {{w|Eratosthenes}, two-thousand years ago, through mathematics alone, had figured out the shape and size of the Earth. He had measured the discrepancy of two shadows on June 21, and had the distance paced out and plugged into an equation and came up with — his answer was about one percent off. We have people like Heron of Alexandria, who would develop the concepts, admittedly very primitive, the concepts for steam engines. You have {{w|Archimedes}}, of course, one of the most unparalleled genius in all of human history, who'd come up with a fantastic war machine for use against the Romans, and he had, of course — and he is the one credited with any number of inventions: the screw that bears his name, his famous concept of the lever. The other thing, too, was the library was a dynamic place. You had {{w|Galen}} — there's another one, one of my favorites. Galen was a medical mastermind. He was so advanced with his medical techniques, his surgical techniques. He wrote a fifteen-book set on the human body, anatomy and physiology, and, I mean, I've seen side-by-side comparison of some his surgical tools with the tools we have today in modern surgery wards. Of course, the materials are completely different, but the concepts, most of the time the equipment itself is virtually identical. | |||

S: A lot of his anatomy is still relevant today, as well. He figured out a lot of the basics of anatomy. | |||

P: But he still believed in the {{w|Humorism|humoral theory}} though, right? | |||

BT: There were still the four humors and concepts were prevalent in Alexandria, but here — Galen certainly understood about the circulatory system. The blood didn't just swish around in the body. I liken it to one of my favorite writers in history is {{w|Lord Byron}}. He contracted a fever, and, of course, the prevailing idea at that point was to bleed the guy. And, of course, he died. I like to think about not just his death but all the deaths that people with Galen's knowledge, the people that built on things he knew, and if that work had been destroyed and lost, just think of what we could've accomplished. Even if you use conservative estimates, all the material had to be rediscovered. | |||

S: It wasn't entirely lost. | |||

BT: No. | |||

S: A lot of that knowledge actually was harbored in the Mideast, in Persia. | |||

BT: Right. In the Arab (''unintelligible'') | |||

S: In Persia. The dark ages was very much a European dark ages, and, meanwhile, mathematics and engineering and medicine and astronomy was thriving in the Middle East, in Persia. | |||

BT: That's right. When they conquered Alexandria in 646, a lot of those manuscripts — there were two things that happened, and I think it shows the two-sided human nature in a lot of ways. The invading Muslim armies, they destroyed a lot of the remaining literature that they considered to be infidel. The Christians had destroyed the pagan literature, and, of course, the Muslims destroyed a lot of Christian literature. But, as you said, not everything was lost, and that's how we know a lot about this place and a lot of references, a lot of fragments of books, and, finally, that we do know about. And it certainly did encourage them to come up with pioneering advances in mathematics. At the same time you had a fundamentalist element which reared it's head among their — in that religion as well. One of the last great ancient cities that had copies of Alexandria's books, not all of them, but a lot of the findings, was Constantinople. And when Constantinople was being assailed by Mehmed the Second, a lot of these scholars managed to escape with some of the books, and a lot of them settled in Europe, specifically in Florence, which is the seat of the Renaissance later. But, the books that were left behind were all destroyed. | |||

S: Right. | |||

BT: So, certainly, certain books were preserved, and great era thinkers, and so forth, were able to build on that, certainly. And that absolutely contributed to their golden age, which, as you mentioned, Europe was in the middle of the dark age when the Middle East was quite advanced. Now, today, in modern times, we see the opposite. | |||

S: Right. That's right. In fact, you can actually trace back some of the seeds of knowledge that led to the Renaissance back through Persia and into the ancient knowledge of the Greeks and Romans back to the library of Alexandria. So there is some continuity there, but, again, there was the thousand, 1500 years of philosophical, scientific dark ages. Interestingly, what I learned from studying that time is that technology still continued to progress fairly steadily in Europe throughout the dark ages. But it was more a dark ages of ideas, of inquiry, as well. | |||

P: What was the core? How would you characterize, Brian, the core feud between Archbishop Cyril and Hypatia? | |||

BT: Well, one of Hypatia's few surviving quotes was "all formal, dogmatic religions are fallacious and should never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final." It's one of the few things, and this did not sit very well with him, at all. This is a person who — Cyril, before he got to her — this is just not a nice man by any standards, at all. He had a grudge against the Jews, just the fact, you know, all the different pogroms he had begun, and he had them driven from Alexandria. That's directly laid at his feet. He also — this is particularly interesting — we talk about debate and coming to certain ideas and discussions. There were different sects of Christianity, like the Novatians and the Nestorians, and all these different people at different slices of opinion on that religion around God or on (''unintelligible'') prime mover, things like that. These debates used to thrive in Alexandria, even among Christianity. He put a stop to that. Him and his uncle, the Archbishop Theophilus, and his uncle had some sects exiled from the city on penalty of death. | |||

S: Well, the church at the time was building its power based upon authority. | |||

BT: Right. | |||

S: The idea was that knowledge descended from authority. | |||

BT: Right. | |||

S: And open-ended inquiry was completely incompatible with that. | |||

BT: Oh, completely. | |||

S: So that was the essence of the conflict, I think, was religious authority versus open-ended inquiry, and we know who won, right? That was the dark ages, right. | |||

BT: To put it — talk about an arena, a more ironic arena. Hypatia was, according to the historical record, dragged from her chariot, pulled into a church, and murdered right there. | |||

S: Her skin was flayed with abalone shells, is how Carl Sagan (''unintelligible''). | |||

BT: Shells, pottery shards, supposedly in reed baskets. They emptied it out at their feet. It was passed out among all the parishioners. In my book, I say it's passed out like some unholy Eucharist. And, in their hands, they all just go at her, and literally hack her and flay her to death. | |||

P: Excuse me, Brian, Alexandria wasn't a theocracy, right? The church wasn't in charge of the political state. | |||

BT: 391 A.D., the Edict of — prior to 391, we need to actually go back to Constantine and 311. Emperor Constantine, of course, he was the victor in an empire-wide civil war, and he chalked his victory up, as many, many leaders throughout history way before him, to divine endorsement. Since gave the Greeks the idea to take Troy the way they did, or (''unintelligible''), all these different deities throughout history. Well, Constantine chalked his victory up to a little-known deity at that time, which is Jehovah, and, of course, he is the one who created a state-endorsed religion. Christianity became the religion of the empire. But he still did allow religious freedom. He allowed other faiths to be tolerated. In 391, the Edict of Theodosius — that took the next logical, or as I had to say evangelogical, step, which was: if we're tolerating, if we endorse one religion, what are we doing tolerating these other ones? So, other faiths were outlawed throughout the empire. And pagan temples were destroyed, pagan priests, parishioners were converted at sword-point. Pagan priests and priestesses were killed, often crucified, despite the irony. | |||

R: And at that point, that was 391, but that wasn't the first major blow to the library, right? That was happening. | |||

BT: That was, yeah. The Serapeum was actually — it was a temple devoted to the god {{w|Serapis}}, who was pretty much — Alexander was unique. When the Greeks came into Egypt, they fused — I mean you had this beautiful cross-pollination of two very high civilizations: Egypt and Greece. | |||

R: Right. | |||

BT: And they were fused, not just in architecture, but in a lot of ideologies and a lot of art. And Serapis, the Temple of Serapis, and all the documents that it had, was a concrete symbol of that. So it was a very clear target in 391, but the library itself did persist. The most basic reason is that we know Hypatia was working there. That she was returning from the library at the time of her murder, and that advances from history right as the upswing, the fundamentalist. Again, we see parallels of that today. Look in the Middle East. Look at how political cartoons are treated. Now the great library has been resurrected in our modern age. The {{w|Bibliotheca Alexandrina}} was created in Egypt, and it houses something like 4 million books and these like 10 billion webpages archived, and it's supposedly a really extraordinary building. But my question is — and I applaud it. There's no question about that, but are they going to be eager to stockpile certain, say, political cartoons or, say, {{w|The Satanic Verses}} by Rushdie or books like that? And, if so, does anybody really doubt that a certain faction would want to see that heathen institution or that sacrilegious institution burned to a crisp again? | |||

R: I think we need to look at it also as kind of a more insidious thing, because I think that often when we think of, say, the great library burning, we think of one big event, when there was so much going on and so much building up to it. I don't know if you know about Matthew Battles, the writer and Harvard librarian, but he wrote a really interesting study about the library, where he suggests that it wasn't just one great fire. He said it was "moldering slowly through the centuries as people grew indifferent and even hostile to their contents". So I think we need to always be on the lookout for that same kind of insidious undercurrent of hostility towards knowledge that could spring up at any moment, while it could've been there all the time. | |||

BT: Well, I think it always (''unintelligible'') -- I definitely agree. That Aristotlian inquiry that is really out of the Socratic method, the basis for the scientific method. These things are just and will always be, I think, a direct threat to certain kinds of people, certain people who have a certain ideology, a certain way of looking at world, and it's something that we have to conscious — I think it's something we always have to fight. We have to step into that arena and stand up for it. | |||

J: So, Brian, I find it interesting to think: it is even remotely possible that any kind of intellectual dark age could happen again? And during your research, what kind of conclusion would you draw from that? | |||

BT: I think it is a possibility. I think it's a terrible mistake for anyone to say it can't happen here, it can't happen again. And I think we have other concerns at this point. First of all, there are still book burnings that happen. We don't just have to point to the Middle East. In Pennsylvania, a couple of years ago, they were rounding up Harry Potter books and rock-and-roll CDs and having this huge bonfire. It was a church sponsored event. So we have it right here in this country. We don't need to go to foreign fronts to see that. Secondly, there's a different kind — I mean, we live in a world of mass production where literature is available so fast, at the speed of light — in 186,282 miles per second, you can look at anything you want in all this information. But at the same time, because of the digital nature of a lot of this knowledge, it can be kind of akin to — has anybody read {{w|Animal Farm}} by George Orwell? The animals had that list of commandments that they all were going to abide by, and slowly over time, that list would insidiously get shorter, but so shorter that they wouldn't actually notice it. It wasn't something sudden. It wasn't anything dramatic, but by the end of the story, when they do realize it, it's already too late. Everything has changed. A lot of the knowledge has been lost. The original decree of this new society has been completely mutated and perverted. So, I think that's something we have to worry about. Think of a digital razor to films and to books. People with any kind of axes, political axes to grind, or any religious axes to grind. I think it's important. A lot of this knowledge does pass through a limited number of hubs, and it is a rapidly diminishing media, if you think about it. So there are certain concerns. | |||

S: Yeah, I agree. This is always an interesting question, and this is something that often gets asked of us: in this modern age, do you really think that there can be another dark ages? And, I sort of think about it in two different ways. On the one hand, we are living in an increasingly worldwide culture with the Internet, with incredible access to and ability to reproduce information. So, it certainly, from that point of view, would be much more difficult for any institution or nation or power to really, completely put the clamp on information and inquiry in the way that was feasible and possible a couple of thousand years ago. But, on the other hand, we definitely see the effects of similar things occurring in pockets, in individual nations, or individual cultures. For example, in the Soviet Union there was the famous incident of {{w|Lysenkoism}}, where the Communist Party decided that this guy Lysenko, that his ideas about genetics and evolution, which were Lamarckian and incorrect, that that was the official state-sponsored genetical theory. And Russia is still, now, 30 years behind the rest of the industrialized world in genetics. They never caught up. It permanently set them behind. In this country, public understanding of evolution and, in fact, the number of world-class, top researchers in evolution in this country is much behind many other Western industrialized nations, and we certainly lag behind that area than we do in many other areas, largely due to the systematic campaign of fundamentalist and creationists against the teaching of evolution. So these kind of insidious, anti-intellectual, anti-inquiry movements can have far-ranging, cultural implications. But my hope is that we have crossed some point where we have enough of a worldwide culture that it would be impossible to do it to the thoroughness and extent of what happened in the dark ages. But, you know. | |||

J: China has their own version of the Internet. | |||

S: That's right. | |||

J: Somehow, they're able to limit access on a national level. | |||

BT: Every June third and fourth, the anniversary of {{w|Tiananmen Square}}, they black out that media that you're talking about, any mention of that horrible event, where all those thousands of protesters were destroyed. So, yeah, I completely understand and agree. | |||

P: That's until that regime falls, though. My personal view is that the regime in China is doomed to failure. Communism has been proven a failure. It's on the ash heap of history. China just hasn't caught up yet. | |||

S: It's interesting to see which way China will go. That's the last great experiment in pretty much exactly what we're talking about. Certainly, since the 1970s, since Nixon and detente with China, the big experiment has been: will exposure, even just through marketing, through commercial exposure to the West, errode China's iron grip on knowledge and information in their own country. I think we're still waiting to see how that's going to play out. But, certainly, the optimists are saying that China will either evolve away from totalitarianism and communism, and others think that at some point, the regime may just collapse like the Soviet Union did. We'll see. That's a very relevant social experiment that's occurring right now. | |||

BT: China just inducted private entrepreneurials and entrepreneurs into the Communist Party a few years ago, so I think I tend to be a little optimistic about that. On the other hand, there's just a concern about any kind of one — communism isn't the only form of totalitarianism. I mean you can have plutocracies; you can have anything at all, but I definitely think — I think it is destined to fall. It either seems to be — I think the creaking is being heard. | |||

S: And now, of course, we've talked about how the Middle East was the repository of ancient knowledge during the European dark ages, and now the roles are very much reversed. And I think it does remain to be seen how the Middle East is going to go in the near future. That part of the world seems to be largely under the grip of very extreme, radical fundamentalist notions, which are extremely anti-knowledge, anti-intellectual, and that could create an intellectual dark ages in that part of the world that could last for a very long time. | |||

BT: Well, the thing is, there was a crossroads in that culture, in which they had more of the moderate element and the hardline element. And unfortunately, the hardline was almost elected or appointed as a result of the constant crusades, crusading parties from Europe, all the times. I think you know certainly know a lot of those holy wars had a lot to do with the evolution of the Middle East into what it is now, and I think that's a good point in the sense that technologically speaking, when people hear dark ages, we're not going to go back to throwing spears and, you know, catapults and stuff. We're looking at an ideological dark age, where you can - I think it's absolutely possible today. | |||

S: Yeah, and that's, of course, one of the reasons why organizations like us, the New England Skeptical Society, exist, because I think at some point there has to just be a fundamental support for open-ended and free inquiry without any oppressive restrictions. That has a certain intrinsic, inherent value to human civilization, but it is constantly being nibbled away at. It really is, and it takes a certain amount of vigilance to continually promote it and to keep the forces of anti-intellectualism at bay. | |||

S: Unfortunately, that anti-intellectualism is embedded in, I think, a lot of our traditions here in America. Even the literary tradition. I mean, who is the villain in a lot of Nathaniel Hawthorne's work, one of the great American writers. It was always the intellectual. Roger Chillingworth from the ''Scarlet Letter''. Dr. Rappaccini, who created a daughter of pure poison. The scientist from ''{{w|The Birth-Mark}}'', who is trying to seek perfection and ends up killing the woman he loves. And Edgar Allen Poe, who snapped that science is a prying vulture. | |||

S: And Hollywood has picked up on those themes. And Hollywood really knows very few themes when it comes to science. They know about the mad scientist, the arrogant scientist, and that's about it. They don't really have any positive ... | |||

R: Don't forget the foolish skeptic. | |||

S: Right, the misguided, narrow-minded skeptic. | |||

R: Oh, there's never going to be an asteroid that will destroy the planet. | |||

P: Or skeptics in a mystical world, is also ... | |||

S: Right. | |||

P: ... a very common theme that comes out of Hollywood. | |||

S: Right. Which, of course, rigs the game against the skeptics from the get-go. If you're a skeptic in a paranormal world, ... | |||

P: Right. | |||

S: ... that's a lose-lose proposition for the skeptic. It's definitely possible to create short-term, and by short-term that could mean decades or even centuries, significant setbacks in the advancement of knowledge and science because of narrow political or social or religious ideology. I think in the long run, it all works itself out, but, again, we say "the long run," that could be after a 1000 years of dark ages, right? And you can only speculate where we would be now as a civilization if that did not occur. | |||

BT: Which is why, I think, Hypatia's story is not only important, I think it is very, very relevant, and now it's part of what attracted me to the story. This is the last time you had a very serious -- that (''unintelligible''), that title fight between rational thought — frankly between pluralistic freedom, and then you have between that blind superstition and blind faith. And we know who won, and then we've all been suffering for since then. | |||

S: Right. | |||

BT: So I think that's really the relevance of the story to me. No one would really choose willingly, knowing what they're talking about, really to choose to live in those 1000 years of medievalism. People didn't travel on average more than ten miles from where they lived. They were cut off from the world. They had no — there really was no education. People didn't bathe more than once a month, because they were afraid it — all the concepts of cleanliness and so forth and opening up one's mind, were shattered, were buried, were held under a thumb until you had it slowly eking out during later eras. | |||

J: Imagine being an intellectual living during that time and how painful it must have been being completly surrounded by people. | |||

BT: It must have been (''unintelligible'') | |||

P: Yeah. | |||

S: Right. | |||

P: That's right. | |||

S: Well, Brian, it's been great talking to you. What are you working on now? What's the next project that you're dealing with? | |||

BT: Well, right now I'm working on — I finished up another book about Japan and China. Interestingly enough, that second book that I have, it has a completely different themes, and it's not analogous to ''Remembering Hypatia'' in terms of its themes, but it does open with another very famous book burning in history, which was the one that was conducted under the reign of the first Emperor of China, of a unified China, I should say, Emperor {{w|Qin Shi Huang|Qin Shi Huang Di}}, who had not only executed scholars around China, but also, we know, burned these books that disagreed with a worldview that he wanted to put forth. Certainly I'm excited about it, and I post a lot of the news and things that I'm doing. I'm going to be talking more about ''Remembering Hypatia'' in the near future, anyway. At rememberhypatia.com I have all the list of events coming up I'm giving. | |||

S: And we'll have that link on our notes page. Well, Brian, thanks again for joining us. It was fascinating talking to you. | |||

R: Yeah, thank you, Brian. | |||

BT: Likewise, and best of luck with everything. I like what you guys do. | |||

S: Thanks a lot. | |||

J: Thanks, Brian. | |||

S: Take care. | |||

BT: Thank you. | |||

S: Well, that was great to have Brian on. It's always a fascinating topic, the whole conflict between reason and fundamentalism. It's a very interesting discussion. | |||

P: It was good. | |||

R: Yeah. | |||

S: Look forward to his future works. | |||

R: Brian's a cool guy. | |||

S: He is. Cool guy. | |||

== Science or Fiction <small>(1:03:54)</small> == | == Science or Fiction <small>(1:03:54)</small> == | ||

S: We have time for Science or Fiction. Each week I come up with three science news items or facts, two genuine, one fictitious, and I challenge my skeptical rogues to decide which one is the fake. There's no theme this week. Sometimes I have themes. So we have three items. You guys ready to hear them? | |||

P: Baited breath. | |||

R: Yup. | |||

S: Okay. | |||

R: I am, at least. | |||

S: Item number one. Again, two are real; one is fake. Item number one: Toyota has unveiled a prototype ''green car'' they claim can achieve 175 miles per gallon. Item number two: oil drillers have dug up a piece of a dinosaur fossil from 2615 meters below the ocean floor of the North Sea. And item number three: some astronomers believe that evidence is mounting for the existence of a companion star to our own son. | |||

P: Companion star! | |||

S: Evan, why don't you start us off? | |||

E: Well, they all sound wrong. Something about that ocean floor doesn't sound right. I don't think we can go down that far below the ocean floor. 26 — it was 2615 meters? | |||

S: That's correct. | |||

E: Can we go that far down the ocean floor? I wasn't aware that we could go. Maybe we can. Hm. The green car sounds plausible. Companion star — that might also be wrong. But, I'll stick with number two. Because that's what my gut is telling me. I just think that's too deep. I don't think we can go down that far. | |||

S: Alrighty. Perry? | |||

P: Yeah, well it depends what ocean floor you're talking about. If it's 5 feet off the beach we can do it. It was pretty vague. Hundred and seventy-five miles to a gallon — that's impressive. Japanese are good at that sort of thing, however. A sister star to our sun. I'm going to say number — I'm going to say that the first one is fiction. I think 175 to 1 gallon of gasoline — is that what you are talking about? A gallon of gasoline? | |||

S: Yes. | |||

P: Is a bit much. So I'll say — and it's a car, not a model car, yeah. That's too much. | |||

S: It's a car. It's a car. | |||

P: Okay. So, yeah, number one is fiction. | |||

S: Alrighty. Okay, Rebecca. | |||

R: Yes. Okay. The hybrid things seems really — it seems doable. I mean, it's a crazy amount, but I think that might be true. And the second one, I'm kind of with Evan on this. That seems really, really deep. I think I'm going to go with that one, because I think I heard — I think I read a news story about the companion star thing, too. I think that's true. So I'm going to go with number two being fiction. | |||

S: Okay. So far, everyone is buying that the companion star is true, and we have two — Evan and Rebecca think that the fossil under the North Sea is fake, and Perry does not believe that the Japanese have a prototype car for 175 miles per gallon. So, let's see. Well let's start with number three, since you all agreed that number three is true. Wouldn't you think that you could see the sun, a companion star, in our own system? | |||

R: Things can be far away. | |||

S: But if it's in our own system, how could it be too far away? Even a small star in our own system would be the brightest star in our sky, unless it were dark. The only possibility is that the companion star is like a brown dwarf or something that does not give off significant light. That one is true. | |||

R: Ah, ha! | |||

S: The evidence that has been "mounting" is the discovery of the alleged 10th planet, right? So {{w|90377 Sedna|Sedna}}, for example — these are planets, depending on whether or not you want to define them as such. They are large, larger than Pluto, spherical, planetoids surrounding the Sun. It's still debatable whether or not they should be actually counted as planets, because they're so far out. But, again, they are like planets, and they're bigger than Pluto. That their orbits cannot be really fully accounted for by our current model of the solar system. Now there's a couple of ways to explain their orbits. One is that at some time, billions of years in the past, earlier on in the solar system, we were a lot closer to some of our neighboring stars, and that their gravitational influence put them in the orbits that they're currently in. But there's another school of thought that says the orbits can be explained without invoking changes in the past. In fact, if we have a dark companion star to our own sun, that could explain the oddities in the orbits of these newly discovered planets out in the edges of our solar system. So this is still not proved. This is still a working theory, but, again, there are those who think that we are moving more in the direction of inferring the existence of this object. | |||

R: Steve, what's this going to do for my horoscope for the weekend? I've just kind of (''unintelligible'') | |||

S: As well as Sedna and Xena, these other bodies are wreaking havoc in the exact science of astrology, becuase now you have to account for their influence on all the other planets. It's just mind boggling. | |||

R: I'm a little concerned. | |||

S: It's very concerning. Now, let's see. Which one should I go to? We had — so Perry thought that number one was fake, and the other two thought that number two was fake. Well let's go to number two: oil drillers have dug up a piece of a dinosaur fossil from 2615 meters below the ocean floor of the North Sea. That one is, in fact, true. | |||

R: Ah, ha! | |||

S: That is science. | |||

E: Wow! Impressive. | |||

S: The fact that it's the North Sea, which means that Perry is right this week. Congratulations, Perry. | |||

P: yes. | |||

S: We'll get to the green car in a minute. So this is the deepest dinosaur fossil ever found. Paleontologist {{w|Jørn Hurum}} was the first to identify that the bone fragment that was brought up by the drill was actually a fossil and, in fact, a dinosaur fossil. This was dug up in 1997, and then a few years later in 2003 he acquired the fossil, and he was able to identify it recently as the leg bone of a plateosaurus, a Triassic carnivore. Normally, drills pick up little bits of fossils, mostly seashells and things like that all the time. This was the largest single fossil fragment ever brought up. During this period of time, about 200 million years ago, the North Sea was a land bridge connecting Greenland and Norway. So this was dry land at the time that this fossil dates from. So a very fortuitous and interesting find, and Hurum gets credit for identifying the species from the tiny fragment, but he says he's very, very confident in the identification. Yes number one: this one is fiction. so Toyota unveiled a prototype green car they claimed can achieve 175 miles per hour (sic). Not totally outrageous, but if you have been following along with the hybrid technology, this is about twice what they're getting now. | |||

P: 175 miles per gallon, Steve, you said per hour. | |||

S: 175 miles per gallon, thank you. Now the hybrid technology, which is really interesting, and this is someting that we maybe want to talk about in more detail in the future, just all of the facts surrounding both hybrid technology as well as hydrogen fuel-cell technology. The hybrid cars that are on the roads now are getting somewhere between 30 and 60 miles per gallon. Although the EPA just changed their rules by which cars' miles per gallon get rated to make them more reflective of actual driving conditions, as opposed to the absolutely optimal conditions that have been used in the past to get fairly unrealistic miles per gallon numbers. So those numbers are all being downgraded. But even still, the best hybrid cars are getting in the 50s. What is being unveiled, and in prototypes, and will probably be hitting the streets a year from now, is the next step in hybrid technology, which are the plug-in hybrids. These are hybrids that you can actually plug into any 120 volt outlet and charge it up. | |||

R: But wasn't that the first stage of electric cars and everything? Didn't we already do that? | |||