SGU Episode 1035: Difference between revisions

Page created (or rewritten) by transcription-bot. https://github.com/mheguy/transcription-bot |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 00:20, 11 May 2025

This episode was created by transcription-bot. Transcriptions should be highly accurate, but speakers are frequently misidentified; fixes require a human's helping hand. |

| This episode needs: proofreading, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

| SGU Episode 1035 |

|---|

| May 10th 2025 |

|

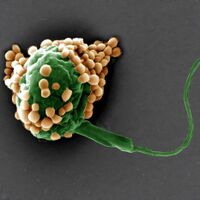

"Stunning microscopic view of a sperm cell surrounded by nutrient-rich particles." |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

“Sit down before fact as a little child, be prepared to give up every preconceived notion, follow humbly wherever and to whatever abysses nature leads, or you shall learn nothing” |

T H Huxley |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| SGU Forum |

Intro

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, May 7th, 2025, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella.

E: Everybody.

S: Cara, Santa Maria.

C: Howdy.

S: Jane Novella. Hey, guys. And Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening everyone.

S: Cara, welcome back. How was your trip it?

C: Was amazing I was gone for a month. Did you guys notice?

S: We did what was the most amazing thing.

E: Yes.

C: Oh, I can't pick the most amazing thing. One of the well.

B: Then what's the least amazing? Yeah, right.

C: I mean, for me, it's China. It's not my favorite country to visit. I'm going to be honest. I do love that. I went and saw giant pandas at a breeding center. That was kind of cool. And red pandas, like right up close and personal. They're sort of just out in the reserve, but then they'll cross in front of you over little bridges and things. And red pandas are just the cutest. They're my absolute favorite.

S: They are cute.

C: So yeah, that was pretty fun. But China on the whole is a little bit difficult. You know, it's like it's a closed country. And so it just feels different. You can't access things on the Internet. Using money there is very difficult. I think I was really excited about Vietnam. I had never been there. So I went to Hong Kong for two weeks, Mainland China, up in the Chengdu in the Sichuan region, and I had really good hot pot, spilled it in my lap, got a horrific second degree burst.

E: 2nd.

C: Oh.

E: Carrots. A really good thing you don't have balls. Did it come with a warning that it was hot?

C: I mean, I knew it was hot, but the the bowl was like flour shaped. And so when I put the soup in the bowl, it just like splashed right over the side. Oh, yeah. It was brutal. So that that put a little bit of a damper on on the trip. But then I I spent a week in central Vietnam. I happened to be there during reunification day. Yeah, yeah, that's April 30th. I know the 50th anniversary of that. So it was like kind of a really big deal while I was there. I was interested and surprised and a everybody's very, very warm towards Americans. I didn't feel any sort of hostility. And I was in central Vietnam. I was near Danang hanging out in like Hoi An hanging out in Hui in a small town called Langko. This was the front lines in central Vietnam. And so, yeah, I was, I was like pleasantly surprised that when I asked people, they were like, it's a big Vietnamese holiday. And I was like, oh, what is it? And they were like, it's kind of like our Independence Day, but they didn't say like from you. Yeah. So, so it was really interesting. There were obviously Vietnamese flags everywhere. The, the hotels were really bumping with a lot of partying and stuff. There was a weird experience where they they closed the main road to scooters. And I I was there with a friend who lives in Asia and is very comfortable on a scooter. So that's how we rode around the whole time. I was on the back of a scooter and we had to take a mountain pass to be able to get to different cities, which doubled our length of time. At the top of this one mountain is a basically like a military Fort, like a post from Vietnam that's now sort of a museum. And there were people doing tours there and they were doing tours in American jeeps. Like it was really kitschy. You know, there's a lot of this kind of propaganda posters and a lot of kitsch around Vietnam, but I, I thought it was really strange that there were Vietnamese folks running Vietnamese tours using American military vehicles with all of the, like, imagery that goes along with it. So it's interesting, you know, knowing that there are people alive right now, plenty of people who fought in this war, who lost their lives, who lost limbs, who lost their mental health, who got diseases from the, you know, horrific chemicals that were used during this war. But also there are people, so many people alive right now, to whom this was it's history in a history book.

US#03: Right.

C: You know, I wasn't alive during this, so I was born very soon after. But to me, you know, it's I was.

E: Born on the 4th of July.

S: That's true. Yep. Cara, just want to point out, just because that you said there are people alive today who lost their lives in the Vietnam War.

C: Oh, I did. Yeah. Oh, that's awesome. That doesn't make a lot of sense, does it? Perhaps. I know, I know.

S: I do know what you mean, but technically that's what you said.

C: I am glad you did point that out. There are people, OK? You're right. There are people alive today who are deeply affected and who lost love. Who know?

S: Yes, you Love Actually lost loved ones. And yes, yes.

C: Yes, so it is. I don't know, it's an interesting thing, history and living through history and not having lived through history and how quickly things can change. Like while I was there, I felt not only so incredibly safe, but really welcome. I actually loved Vietnam so much that I've added it to my list of there are about four countries that I would like to live in if I leave the US And I've added it to my list because I enjoyed it that much. But to think about how unstable it was not that long ago. I mean, and of course all of the whatever we won't get into the politics of it, but how how difficult the relationship was and all of the mistakes that I don't want to call them mistakes, the very bad things that the US.

S: Did bad choices bad? Choices.

C: Yeah, yeah.

S: But we were younger because like you think like I was born in 64. So essentially the Vietnam War was the 1st 10 years of my life. And in our family, in our household, it was just the war.

C: Right.

S: And so I always just heard reference to the war. I thought there was one war, you know what I mean? Like in my mind, in my childhood, like 5-6 year old mind, there was just this one war.

C: Yeah, like the world was at war out there, so.

S: And yeah, that's always been going on. Like there's only this one war and then.

C: That's very 1984.

S: When the war ended, it's like, oh, the war ended. There's no more war, you know.

E: Right, that's that.

C: I never see that. Again. I went into this one shop that I really, really liked where they, they had a lot of propaganda and kind of young artists reimagining things. And they sold a lot of T-shirts that had pretty provocative statements about communism or about, you know, these different inflection points. But one of the the shirts that I really, really loved, it said Vietnam. It's a country, not a war.

S: Yeah.

C: Because so many people only relate to an entire culture of people because of of the war in Vietnam. But yes, when I hear the word Vietnam, I think of the country.

S: Yeah, but that's an artifact, that change of media as well. Like if every every time you're seeing Vietnam or people speaking Vietnamese, whatever, it's in the context of the Vietnam War. That's what you were associated with. I told you guys, like when I went to Vienna and I heard people speaking German there, I realized that oh, holy shit, every single time pretty much in my life, I hear somebody speaking German. They're a Nazi in a movie. And so like, that association was so strong, I didn't even realize it, you know?

C: And it's so dangerous. You know, I think about just this idea that there's a whole beautiful culture, a whole interesting people. And propaganda did that, right? Like it was all propaganda. And when you see Vietnamese propaganda, that to me was some of the most fascinating is seeing all this Vietnamese propaganda. You know, that people sell poster. I actually bought some of the posters. I think they're really interesting. And seeing that and thinking, Oh my goodness, look at all of this. And then going, we have the same thing, like every time there's a war, it's one side making all these claims about how they're superior and that other group is evil, and then it's the other side doing the same thing. It's.

E: True of everyone, it's.

C: Fascinating.

S: Yeah. And that that's why it's so good to visit other cultures and get different perspectives and be cosmopolitan, right? You know, you get, you're not trapped in this very narrow perspective.

C: Oh, absolutely. And, and just to be lucky enough to be there on this like, really important day and to talk to some of the people about it. But yeah, I had a great time. 00 and I have news while I was gone. Guess what happened? Breaking news is only a few days ago, actually, the Board of Psychology issued me my license.

US#05: Oh.

C: Yeah. Thank you. I'm now a licensed psychologist and do not have to practice under supervision anymore.

S: Awesome.

Quickie with Bob: Nuclear Fusion Rocket (08:19)

S: All right, Bob, you're going to start us off with a quickie. What's this about a nuclear fusion rocket? What? No way.

B: Well, yeah, I mean, they're working on it. They're working on. They don't.

S: Have it's not ready yet?

B: But I like to put their ideas. So this is, yes, fusion rockets in the news. This is Pulsar Fusion. It's a UK based aerospace startups founded by entrepreneur A Richard Dynan. And they released some plans relatively recently and I was quite intrigued. So they see nuclear fission rockets as a, as a big thing They did. They do say that, but big in the midterm. And I've been waiting decades for that damn midterm and it's not happened yet, but I apparently it's coming. They say that if you want to move a lot of equipment to Mars and through deep space, then rocket exhaust speeds become even more critical, obviously. And they, they call fusion the king of propulsion, which I can't disagree with. So they envision, it's interesting, they envision fusion space tugs in orbit, multiple space tugs waiting in orbit to attach to rockets that launch them the Earth and approach them. And they, they will dock to the side of the rocket. And of course, they would have to be built in a way that they can actually dock and, and then be used as fusion propulsion to speed them on the way wherever, wherever they happen to be going. So that's a kind of a different interesting idea. And it makes a lot of sense because you can't launch fusion rockets from the, the surface of the Earth. So you'd have to kind of do it once you're out into space. So that's an interesting design, kind of creative. I hadn't seen that before. Now. Their design is Magneto inertial fusion, which we haven't talked about much. It's kind of a hybrid fusion approach. Jay. Yes, thank you. It fuses deuterium and helium 3 and it does that by rapidly compressing a magnetized target on the the plasma compression happens in repeated pulses, which creates bursts of fusion energy rather than maintaining this continuous plasma confinement as other methods. So here's some of the stats. This, I mean, obviously this is not proven. It hasn't been accomplished yet, but they're working on it. They're planning on making this happen. They didn't give a time frame of when it could be completed. Just, you know, steps to get to that, to those final prototypes or whatever. But some of their some of their numbers are interesting. For example, going to Mars with a chemical rocket is typically 7 to 8 months. They said with their fusion design, it could be four months. So they cut that in half, which is, which is pretty slick. But what really got my attention is specific. There's specific impulse measurements which we've talked about on before. It's it's related to the efficiency of the fuel usage. So the higher the number which is in seconds is the better. So chemical rockets have a specific impulse of 450. Their design, they say is 10,000 to 15,000 seconds specific impulse, Steve, That's that's, those are some damn big numbers. So, so that could imply that they could burn their rocket for far, far longer than a chemical rocket depending on how the fuel is used, though. And typically those in those scenarios that there's, there's less thrust. So there's a lot of variables to take into account, but an ISP of 10 to 15,000 is just like, wow, jaw-dropping. This one is even a little bit better for Saturn. Chemical rockets could take 6 1/2 years. They say they could do it in a year with this technology. Once they perfected a year, that's, you know, a lot of years saving. And they threw a number out there of how much money it could save in U.S. dollars. They said $1.2 billion it would save.

S: So faster and less expensive.

B: Yeah, apparently both. Yeah, that's what they're saying.

S: Which makes sense because you know less you have to. You don't have to make time for.

B: Five years CEO Richard Dynamite, he made an interesting point when he said people say doing fusion on Earth is proving to be really hard doing it in space must be must be a crazy proposition but actually there's a lower bar in space part of the problem is doing fusion in the atmosphere and that's correct you don't need to create a vacuum in space. It's already there. But if you're going to do this on the Earth, you're going to, you're going to need that. And that's very, it's expensive, it's complex, it's a pain in the butt, especially when you need big vacuum areas of in, in, in close to vacuum. The other angle here is that the fusion reactors on the Earth are they're being made to, to make cheap, plentiful energy, right? That's the goal that you want to make as much energy as you can as cheaply as you can. And they will be able to do that once they have a nice reactor working. But for fusion rockets, though, it's a different deal. You don't need to be efficient. You don't need it to be cheap. You just, if you make it work that that's probably going to be good enough. So space based fusion propulsion seems to have a lower bar technologically and atmospherically. And if you think about that joke for a minute, I think you're going to really like it. This has been your lower bar quickie with Bob. Back to you, Steve.

S: Yeah, it's interesting to think about that because it using fusion to make electricity on Earth is really hard for a lot of reasons that are just don't exist in space. If you're using it just for propulsion, it doesn't have to be sustained. It could be putts like putt. Putt putt doesn't have to be the sustained fusion. We don't have to convert it into electricity, right? You don't have to, again, create a vacuum. And it's actually a lot easier technologically to do that.

B: But by the way, they also said that they that it can also be used to generate power. So they said that you can get to your destination with two megawatts available. Like damn. So that's pretty. Slick, right?

S: And it doesn't have to be cheaper than solar. It just has to be cheaper than chemical rockets, which are really expensive.

B: Right, right. And don't forget those, the, the deeper you go, those solar becomes less and less helpful. So, so for deep space, you, you got to carry, you got to. Carry on me Bob Bob supplies.

S: But what I meant was like on earth for power few a fusion reactor would be competing with solar power for energy for the cost of energy or for or with right or with wind. But it but it as a propulsion system, it's competing with other propulsion systems which are all really expensive. So again, yeah, the calculus gets a lot more favorable. So yeah, we we may see fusion Rocket just before we see fusion power.

B: I, I think we might, I think we might, and it's funny because we might even have the potential to, to create, you know, working fusion, fusion reactors on the earth, but it's like, it's just not going to be worth it. It might not be worth it for them to do. It's like, sorry, it's just, it's just not going to be worth it. It's just, it can't compete, you know, with, with solar and wind and all that and all that stuff. So that's that's a a future we may encounter where like, holy crap, it just never happens on the, you know, it never happens. On Earth with great power. Generation because it's just not worth it. We got but but it's a good problem to have because that means there's other cheaper alternatives. Which is fine, but I I want to see it in space and as we've said in our forget.

S: You're, you're breaking the the law of the quickie, Bob.

B: All right.

S: Jay was on the edge.

E: It's. One of quickie dynamics.

News Items

Falling Space Debris (15:10)

S: Speaking of space J, what comes up has to come down. Right, right on Earth. That's very interesting way to put it.

J: Yeah, Alright, I wanna, I wanna start with a question. Yeah, 'cause I'm constantly looking up into the night sky. You guys have seen satellites in orbit, right?

E: Yes, Oh yeah, many times.

J: Yeah, I mean, basically the other than the space station, which I was tracking for a couple of years, I was, you know, whenever it was passing overhead, I was, I was watching.

E: It it is neat to see. That's cool.

J: I've seen satellites but they're just literally a pixel of light, there's like nothing to it. However, I have never seen a satellite enter the earths atmosphere. Have you guys ever caught that?

S: No, no I don't.

US#03: Think. Wait.

B: Yeah. Wait, what did I see? No, I didn't see. You're right. Not entering no.

S: Unless something that I thought was a meteor was a satellite reentering that's.

B: True, I guess it's. Piece or pieces of something that broke. Do you remember that meteor we saw back at mom's house looking That was the best I've ever seen. Broke into and it left a trail that persisted. You could see that. That trail was mind boggling. I loved it. Loved it.

J: So this is this is a news item that I stumbled on recently that I found to be, you know, really interesting, particularly because what the future holds. So there was a considered to be a very rare and complicated field operation that happened. European scientists actually pursued a falling satellite in a business jet. I'm assuming they mean like a Learjet and they did this to collect data on what is considered to be a literally a little understood but potentially pretty serious environmental issue. And this is essentially satellite pollution in the Earth's upper atmosphere. Specifically when the satellite burns up and breaks apart and everything, you know, what is it putting into the atmosphere? So on September 8th of 2024, a retired European Space Agency, the satellite that was retired called Salsa SA LSA. This is one of four satellites in a something called the Cluster mission. This particular satellite reentered earths atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean. So they they took off from Easter Island and it was a multinational research team. I guess it was getting some hype because of you know what they were trying to do. You know, this was a really crazy way to to gain data, right, to like fly in a commercial, you know, in in a private Learjet style jet to go up and go super high and see the satellite come, you know, come down into the Earth's atmosphere. So what they wanted to do and what they successfully did do was they were able to capture the event. They had 26 high speed multi spectral cameras and the team successfully recorded the fragmentation and the chemical signatures of this disintegrating spacecraft. Now their findings were presented in April of 2025 and that's why we're talking about this now. This was at the European Conference on space debris in Germany. This is all important data to collect because approximately how many satellites do you think re enter the Earth's atmosphere on a daily basis?

US#03: Daily, daily, daily.

B: Satellites.

US#03: I'm 20.

B: How many?

US#03: No. Oh my gosh. Every day too high.

J: Evan, I'm curious to hear what your number is?

US#03: If if it's one that seems high.

J: So it turns out it's, it's on average 3 satellites a day, Jesus, which is over. It's pretty much, you know, it's over 1000 a year that that's right now. That's crazy. You have 1000 satellites re entering the Earth's atmosphere. I think that's a lot, you know?

E: Maybe, yeah, I must be woefully ignorant about the number of satellites that are up there. Is there 100,000 items up?

J: There, there is a top on Evan. Oh my God, there's so much stuff. Now keep in mind we have these mega constellations that are going up now by SpaceX and then Amazon's going to do it and this is going to blow out that three satellite a day number. Like it's good. That number is going to dramatically increase and it's going to and it's going to be it's going to happen very quickly, right? It's going to be happening within the next couple of years. We're going to start to see a lot more reentries happening controlled.

E: Reentries.

J: Well, you hope. You hope that it's controlled enough where they can dump it in the ocean or you know you don't want to definitely don't want any of this happening overpopulated areas, but they're they're they're supposed to like there's some protocols that have been put in place where they have to meet certain criteria in order to to re enter right meaning that they're.

C: Really small.

J: Corridors they.

C: Actually.

J: Make it think.

C: Really, I figured they'd burn up in the atmosphere.

J: Yeah, well, that's what I thought. But OK, so Starlink is launching thousands of these of their their Starlink satellites into orbit. And these satellites, they do technically they burn up in the atmosphere, but that that process of them burning up in the atmosphere, even if they do burn up in the atmosphere, it's not like this routine thing that, you know, yeah, comes down, burns up in the atmosphere. Whatever's left us, you know, hopefully get stumped in the ocean and we never have to talk about it again. That's not what's actually happening. So when satellites incinerate. Unfortunately, they release metallic aerosols into the upper atmosphere, which is part of the atmosphere you don't want to mess with and particularly aluminum oxide. And that can damage the ozone layer and it can alter Earth's thermal balance, right, by reflecting solar radiation, which, you know, depending on how you look at it, you know, that could be a good thing, it could be a bad thing. So these these are definitely, you know, well known and well established mechanisms in atmospheric chemistry. And the amount of aluminum oxide released into the atmosphere during re entry is a it's a complete mystery. But but now we're on to it, right. So we figured out a way to essentially find the data that we need in this first Test that they did, you know, it was definitely they didn't know what the results were going to be. They had no idea if they were going to even find anything. But here's what happened. I thought I thought it was pretty cool. So they they according to Stefan Lowell at the University of Stuttgart, he said it was unexpectedly faint, meaning they didn't capture a lot of light. And this the reason is that the satellite probably fragmented into super small pieces that would have meant less light, right? Because you there was, there's, even though there might be more of it, each one individually produces less light. And it's not like combined together anymore, right? So the team were able to track up the breakup for about 25 seconds and then they lost sight of it as it, it, it descended down to about 25 miles in altitude. So they did collect spectral analysis of that fragmentation cloud and it revealed chemical traces of lithium, potassium and aluminum. And these are materials that you don't want in, in the atmosphere. Now, it's unclear how much of the vaporized material, you know, turned into an aerosol form. And will it have atmospheric effects? At what volume with with the material have to be at to, to have atmospheric effects, you know, versus how much of it, you know, turned into a microscopic debris that came all the way down to the Earth's surface. The titanium fuel tanks, as an example, from the Salsa satellite say that three times fast. They think that those fuel tanks survived and they landed in the in the Pacific Ocean intact. And that is definitely a plausible outcome for larger and sturdier satellites. You know, that is a concern too, because that debris could be dangerous. But you know, this this is not what they're specifically studying. So getting back to Starlink to and to answer Cara's question, you know, these are new satellites, they're heavier than most people think and they're larger than most people think. So what do you guys think that a Starlink, you know, single Starlink satellite weighs?

E: 8 tons I was.

C: Going to say like one ton.

J: So they're coming in at 2750 lbs.

C: Right here.

J: Yep. Or 1, you know, 1250kg kilos. Now SpaceX says yes, they burn up completely and flowers come out when they burn. You know, like, right, Like there's like nothing to see here. But they did acknowledge that some fragments do occasionally reach the ground when when they come back in. So, you know, again, these are bigger than we thought. You know, there's a ton of them. There's going to be a ton of these reentering because they, they don't have an incredibly long lifespan. So they're just going to be constantly coming back down and replenishing and coming down and replenishing. So there is a few things of particular concern. So one of them is molten aluminum, right? So as a satellite disintegrates the aluminum compounds that are in it, they they melt and they can either vaporize into aluminum oxide aerosols or they can cool into nano and micro micrometer sized droplets. Those two eventually fall to the Earth. Of course the aerosols don't. The aerosols are the are the ones that pose the most risk to the ozone and to the climate. And the researchers, they, they just can't quantify how much aluminum takes what form yet, right again, because this is the initial study that that's going to set off. It's the flick of the marble that's going to set off a whole bunch of studies to come. So that's the real issue. We have a, you know, we have a data gap, you know, with over, like I said, with over 1000 re entries per year, we could potentially be injecting a large amount of these exotic materials into a very sensitive layer of our atmosphere. You know, we don't want to do that. We don't want to do anything that's going to make global warming any worse. We don't want to have any bad negative health effects. If even a small percentage of it is, you know, turned into aerosol and it's up in the upper atmosphere, there could be a cumulative impact that could rival other existing pollutants that we are very well aware of. But of course we won't know until they they do further study. So what comes next? You know, they have, there's other cluster satellites, the Rumba Tango and Samba which are part of that is set that I told you about before. They're going to come down this year and next year and they're unfortunately, you know, they're going to happen during daylight hours, which is not ideal, but it still will still be able to collect data on it.

S: Yeah. So whenever you do anything on that scale, you got to really track it like we're, you know, we're putting thousands of satellites up, is going to be thousands of satellites coming down every year. Yep, it adds up.

J: Just another little thing to worry about team.

S: There's a lot of issues with space, you know, just the sheer amount of space debris. We've talked about this before. It's becoming a huge problem.

B: Oh yeah man, just waiting for the the event to. Happen the event.

S: The cascade of satellites crashing into other other satellites.

B: Yeah, the Kessler Syndrome.

S: All right, Cara.

C: Yep.

What Makes People Flourish (25:46)

- What makes people flourish? A new survey of more than 200,000 people across 22 countries looks for global patterns and local differences [3]

S: What does it take to make people flourish?

C: You know, I like this story because it's a good news everyone, Hey.

B: Good news.

C: I feel like we don't have that often.

B: Not enough. I got some good news too this week, so you go first.

C: OK, so a new study was published. Where was it published? I'm about to tell you in Nature Mental Health just about a week or two ago called the Global Flourishing Study, Study profile and initial results on flourishing. And really this is one of those large multinational multi research site studies where multiple authors contributed. We're talking a longitudinal panel study of over 200,000 participants across 22 different countries that span all six populated continents. They use nationally representative sampling and they intend to collect data for five years. And the idea here is to assess aspects of flourishing and possible determinants of flourishing. But what is flourishing? Well, I'm going to read you a quote directly from the publication. Flourishing is an expansive concept. And then there's like 6 different citations after just those words. And the working definition underpinning the GFS, that is the global flourishing study, has been, quote, the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person's life are good, including the contexts in which that person lives. So then they dive into different aspects of that definition and they further break it down into different, what they call well-being domains. So what do you think some of these different domains might be that make up how we measure, or how these researchers at least have decided to measure flourishing?

B: Health.

C: OK, yeah, they talk about physical well-being.

B: Happiness.

C: Happiness is emotional well-being.

B: Yeah, that emotional, mental.

C: What's another financial Financial? Yep. And they talk about what they call material well-being, which they call financial security.

S: How about liberty? Freedom.

C: Interestingly, they actually don't talk about that, but they do talk about volitional well-being, which they define as character.

S: OK, so sort of their choice.

C: And they also talk about cognitive. Yeah, we already did physical. Yeah, they also talk about cognitive well-being, which they they define. It's a little bit weird. They're well-being domains I wouldn't choose. But basically they talk about meaning. So we've got health, happiness, meaning or purpose, character, financial security. And then what do you think the last one is? We're leaving something really important out here. Do you exist in a vacuum?

US#03: Oh, social.

C: Right. Yeah, relationships.

US#03: Yeah.

C: Yeah, so and then they define each of them. So relationships, for example, is the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person's social life are good. So they go through and yeah, what they want to do and what they did is they came up with basically an index of well-being across all these different domains. And they just used basically it's, this is a big data study, right? 200,000 people, ask them a bunch of questions, ask them all the same questions, which they do later define as both a study limitation, but also I guess a boon for the study. So I kind of want to stop there and not give you all of the results. But before we go into the result, which I can't give you all of them anyway, it would take too long. But before we go into some of the results, why do you think it's both a good thing and a bad thing that they asked all the different people in the study the exact same questions?

S: Well, you can. You can do statistics and you can compare them.

C: Right. Yeah, it's it, it it's much more feasible to do a large statistical analysis when you do a study this way. But as they define it, they did this study in an etic way, not an emic way. Do you guys know the difference between those two sociological concepts?

B: Say those two words again.

C: Etic, ETIC versus emic. EMIC, Oh.

B: Damn, I don't know the comparison.

C: So in an etic study, what they're basically doing is they're saying I am outside of your culture and I'm going to look inward and ask you questions and then make comments about your culture. Whereas an emic study utilizes researchers or individuals living within that culture and formulates the questions to be meaningful or contextualized within the culture. So. Like endemic, Same kind of word. Maybe it's the same word. Yeah, I'm not sure actually. Well, what's the word on that sometimes. But basically we do see more of a movement towards emic approaches in sociology overtime. When we think back to like super colonial approaches, they were all very etic. But it does in this specific situation allow direct comparisons. The problem is some context is probably lost and there there's always going to be an implicit bias then, because who defined these questions, right? And is that perspective now going to measure that more? So in a culture that utilizes some of these different these measures? We don't know. So, so it is important that they, they list that as a limitation of a study, but they also talk about why it made it really easy to compare all 200,000 participants to each other, to compare different countries, different age groups, different genders, all these different ways that you could slice and dice this demographic data. And they asked a lot of questions. They asked things like, let's see, how old are you? What's your gender? Are you married? Are you employed? Do you attend religious services? How much education do you have? What's your immigrant status? What country are you from? What was your relationship like with your mother growing up? Your father growing up? What was the financial status of your family growing up? Was there abuse? You know, they ask so many different questions to try and understand what people's life is like now and what they went through throughout the lifespan to get to where they are today. And then they made a bunch of comparisons and they found some kind of interesting outcome. So let's start with what they basically define as who is flourishing and why. That's a big question that they asked. Who is flourishing and why? When it comes to age, what do you think? Who are flourishing the most across the lifespan?

S: I think generally speaking, the older you get, the more you're going to flourish.

C: That's true, but a lot of studies previously didn't show that. A lot of studies previously showed that older adults were the ones who were struggling the most, but this study shows that it's relatively flat between about 18 to 50. And then you just see a slow steady increase in flourishing. And the highest flourishing is amongst the oldest group. So yeah, usually in the past studies showed AU shaped curve where you had this dip in the middle in middle age, but you had kind of higher earlier and older. But not this study. It just shows kind of a slow, steady increase.

S: Yeah, well, you get better at the whole life thing.

C: I find this one really, really interesting. They're showing that being married have higher flourishing scores across the board. So it goes married, then widowed, then domestic partner, then single, never married, then divorced, then separated. But they don't divide it by gender. And so I would be really interested to see because previously study. Previous studies have shown that married men have the highest at least life satisfaction, followed by single women, followed by single men, followed by married women are at the bottom. So so it would be interesting to see they're flourishing scores divided not just by marital status but also by gender. They do look at gender and they find that gender is pretty even across the board. But there are differences from country to country. So in some countries, women flourish less than men, but across the board, when they look at all of the aggregate data, it's pretty, pretty even 7.19 is, you know, they have this like this measure that they use 7.19 for men, 7.12 for women, pretty much the same. This one might surprise you. What do you think across? And I don't, I know I didn't tell you what the 22 different countries are, but what countries do you think people are flourishing in the most?

S: I'd say high socioeconomic status countries, you know?

C: Right. Yeah, you'd think kind of richer, richer countries, countries with more wealth. So like the United States is on the list and it is definitely in the bottom 3rd.

B: That good, huh?

C: And they look at it with and without financial indicators. And across the board, the number one country was Indonesia, followed by Mexico and then the Philippines.

B: Mexico. Excellent.

C: Yeah, from there, right up in the conversation, quote, Indonesia is thriving. People there scored high in many areas, including meaning, purpose, relationships and character. Indonesia is one of the highest scoring countries and most of the indicators in the whole study and Mexico and the Philippines also show strong results. Even though these countries have less money than some others. People report strong family ties, spiritual lives and community support. The lowest scores were in Japan and Turkey. And even though, for example, Japan has a strong economy, people reported lower happiness and weaker social connections. They also think maybe long work hours and stress contribute to, to lower flourishing scores. Turkey, obviously there they they describe political and financial challenges and you know, just difficulty with secure like individual security. So they talk about how it's surprising that richer countries like the US and Sweden aren't actually flourishing as well as some others. They do well on financial stability, but their score?

E: Doesn't translate necessarily to across the board flourishing.

C: No, because that was only one of the measures they're showing lower scores in, meaning lower scores in relationships. They found that countries with higher income across the board do tend to show lower levels of meaning and purpose, and then countries with higher fertility rates often have show higher ratings of meaning and purpose.

US#03: OK, that seems reasonable.

C: Yeah, yeah. I mean, it's interesting when you look at these big takeaways because you can sort of predict some things and other things. It feels a little like science or fiction where you could make a case for it to go either way. Like one of the things that they talk about, and we've seen this across other studies, is that individuals who are highly involved in religious services tend to have higher ratings of flourishing. So those who go more than once a week are higher than those who go one time per week, higher than those one to three times a month down to a few times a year down to never. Never is on the very, very bottom. And they saw that this was the case even in a secular countries that were more secular. And so, you know, we've talked about this in the past. It doesn't really necessarily have anything to do with religion per SE, but it has to do more with community. So they cite the the literature in the psychology of religion where they talk about things that they call the four BS belonging, bonding, behaving, and believing. So belonging is social support, bonding is spiritual connection. Behaving is cultivating character and virtue through practices and rituals and norms and then believing, which does contribute to hope, forgiveness, spiritual convictions. So, you know, they do include the actual act of believing as something that contributes, but this is not the main sort of predictive variable here. We know that people who attend religious services tend to have more community, and that seems to carry a lot of weight there. But they also found that people who go to religious services reported more pain and suffering. And it's hard to know if that's because it's sort of a bias, right? They're going because they're experiencing more pain and suffering. That's why they're seeking out religious community or some other reason. And of course, adverse childhood experiences do have some impact on flourishing. If you were a kid with excellent health, you are it's the most predictive of you flourishing later in life. If you're a kid who had a good relationship with your mom, if you went to religious services, if you if your family was financially comfortable, if you had a good relationship with your dad, that's less predictive. You tend to be flourishing more. If your parents were divorced, you had financial hardships, they were single, your parents died, you your health was poorer or you experienced abuse. That experiencing abuse was was the most predictive of low flourishing, which which makes sense. There's not a lot of like big Wows here, but the, the main take away is that it's very, very hard to to pick one variable. This is a very complex interplay of a lot of things and it is probably very, very culture bound. And so this massive group of researchers are excited to continue to dig through the data and to continue to ask questions because we don't have a lot of studies on things like flourishing. We have a lot of studies on what happens when things go wrong, but it is exciting to say, OK, what are some of the reasons that people are feeling fulfilled in life and that they're doing well, and how can we learn from those reasons?

S: Yeah, and it's good to look at these like just big end point kinds of studies, like flourishing or happiness or whatever, because I do think that in life people do a lot of things that they think will make them happy or think will make their life better, but they actually end up doing the opposite, right? Like working really hard to make money. I think, oh, money's going to make me happy, but you're working yourself to death and you're miserable. You.

E: Know if the problem is. Until you do it, you don't know that.

S: Well, but it's not like you don't have 8 billion other people on the planet that you could sort of look at and get. You could, you know, you could learn from other people's life experiences. You don't have to necessarily make every mistake yourself. I know generally we do. But that's what mentors are for, and parents and you know, and whatever you know, people.

C: And reading.

S: Yeah, and reading.

C: Science, you know, like talking to to or reading what these researchers are finding. But I, I, I will be interested in more kind of culture bound and culture specific examples because I think it's really easy to say, OK, this country versus that country or people who do this versus people who do that. But where are all of the moderating and mediating variables here? Like really understanding not just that these are interesting predictors, but these are how the predictors affect one another. I think it can get complicated really quickly statistically, but it could also give us a wealth of information.

S: All right. Thanks, Cara.

C: Yep.

S: All right, guys, I'm going to talk to you about heart transplant.

Pig Heart Xenografts (40:52)

C: Cool.

S: You know that we have a.

E: Heart to heart.

S: We have a we have a huge deficit in organs for transplant, right?

E: I imagine that's always the case.

S: So in the US alone, there's generally speaking over 100,000 people on the waiting list for an organ transplant, but only about 23,000 organs become available each year, and about 6000 people die each year while on the waiting list.

C: And that's for all organs.

S: Yeah, OK. Yeah, but it's just the US. Just the US, I was the number of the donor numbers are a lot bigger in the world. Yeah. And this is a problem that could be solved that just people, more people become organ donors. There would definitely be a huge benefit to, you know, the health of the world, you know, if we had essentially an unlimited supply of donor organs, if the supply was greater than the demand, like that wasn't the limiting factor.

C: Of course.

S: Yeah. So how do we get there?

C: Grow them.

E: We line them up, take their organs, grow them. Yeah. Grow.

C: Well, yeah. It's like if you look at organ donation, I don't know. I work in a hospital and I've worked with a lot of individuals on the heart transplant list, like with the psychology of what it means to get a new heart. I mean, it's really intense, right? And so I have noticed when I'm, when I'm doing the inpatient work that there's a massive difference in the parameters and just the like agidity between the heart transplant patients and for example, a kidney transplant patient. Yeah, because it's just easier to get a kidney.

S: It is.

C: There are more kidneys.

S: Because people can donate one kidney.

C: Yep, can donate. Yes, like a family member can give you a kidney and then you have a kidney. Can't give you a heart? Somebody. Can't give you a liver. I can't. Exactly. Well, and even liver transplant you can give a little less intense. Yeah, because you can give a lobe of a liver and it regenerates.

E: That's enough to keep someone alive, yeah.

C: Heart is a very, very different animal. Yeah. Like it's and the the threshold for how healthy you have to be to be able to get that heart or not healthy, but how capable you have to be to be able to get that heart is much higher.

S: Yeah, so that's that's a good point. And that raises another wrinkle here is that the numbers I just gave you are a massive underestimate of the demand because people don't even get on the waiting list. If it's like you listen, you're, you're never going to get there in Oregon, right because. You're yeah, I saw a lot of patients like, yeah, you're just they fail out of the actual. Yeah, they're they're they're already filtered out at the first level pre screen.

C: Yeah, they're pre screened up for transplant.

S: Not because it couldn't work, it's because like, there's no way we're going to get that far down the list to get to somebody with your characteristics, right? You're a high. Risk or whatever. So just forget to have no point even putting you on the list so. But again, if if the source were no, no limit, then a lot of people who don't even get on the list would be able to get a transplant. We know somebody, a very dear friend of ours, Michael LaSalle, who died on the waiting list for a heart transplant and actually didn't even get on the list. They were like, yeah, you know, you know he. That's hard.

E: Yeah, and this didn't develop later in his life that he needed it. They knew early on. Right. It was.

S: It was congenital. He was born. He was born with with.

E: Organs with a defect.

S: With a heart defect and his whole life was like, at some point it's going to get bad enough that you're going to need a transplant. And then they said it's too bad. It's like he was waiting, waiting, waiting. Oh, it's too late. It's.

C: So hard and even, I mean, I've met patients who were eligible, who made it to the top of the list, who got a new heart and then there was some rejection or some sort.

S: Of oh, yeah, it's not a guarantee either way. Yeah. All right, So what are the options for, for alternatives to organ donation, right. Carrie, you mentioned growing them. What do? What do you mean by that?

C: Well, I mean like organoids or something like that. So whether we're growing it in another animal or in a, in a Petri dish, like basically that's been a huge, you know, goal, right?

S: It's tricky because it's hard to get the organ to develop properly outside of the environment of a full Organism, but that's one approach. Another approach is to print them with stem cells, right? But then you need a scaffolding and usually those are obtained from the organ itself. So it doesn't really solve the problem. You need the donor organ to then you denudative cells and you 3D print stem cells on it. The only advantage there potentially is that you could use stem cells derived from the recept, the ultimate recipient, right? So reduces rejection. But then we're not anywhere close to that at this point.

C: So what about animal?

S: Like, there you go.

Voice-over: Right now we're talking about cadavers, but yeah, animals.

S: Animals are, in my opinion, the the, the the best chance and the closest for some organs or for the heart. The heart is different than the than the liver and the kidney in that you can make a mechanical heart. You can't really make a mechanical kidney. I mean, you can, it's a. Dialysis.

C: That'd be so complicated.

S: But it's really you can't have it in inside the patient, right? But yeah, but there we might be able to at some point make a mechanical kidney and we do again, we do have them, just not really for transplant them. We're just for dialysis.

C: But not liver.

S: But not liver. It's really not anytime soon like a bionic liver. It's not not even on the drawing board at this point in time.

C: But yeah, lots of patients are on bridge to transplant. We're just waiting for Heart and they're on LVAD for like exactly while.

US#03: They're yeah, keep, keep there.

S: So there is a bridge to transplant and then there's the ultimate transplant. And then there might be a retransplant. So let's talk about pig hearts for xenografts because again, hearts are difficult and don't, we definitely don't have enough to go around. And you know, we were nowhere close to printing hearts or growing them just in a, in a, in a VAT or whatever. But what you can't do is genetically engineer, genetically modify a pig so that it has something more like a human immune system. And then you basically are growing. It's a xenograft. Technically that means from another species as opposed to an allograft, same species, but it's a xenograft that behaves like an allograft because you've genetically modified the immune markers on it. And then you just just raise a pig, right? You just clone these pigs, you raise them up, you know, and then you harvest their organs. It's the lowest tech way to do it. And the the highest tech aspect of it is the genetic modification. And we got that like we are all over that, you know, I mean like that we have the technology to do the genetic modification we do every week and we could make clones so we could do. So essentially the technology is to you take a pig genome, you make edits to specific genes that that again alter the immune system so that it won't be, it won't look like a different species to the intended recipient. And then you clone it, you put that DNA into an embryo where it's the DNA was removed. And then you induce it to form, you know, to reproduce and divide and form a fetus, right. So there's a company already doing that. And they just that this is the news item is they've, they've completed a trial where they were, they they were, they're donating pig hearts into baboons. They did 14 transplants. The 14 baboon recipients survived for at least several months, with the longest surviving one being 21 months, which is a pretty long time. So and then in one, in one of the cases, they followed up the xenograft with the genetically engineered pig heart with an allograft, basically another baboon heart, because they wanted to just proof of principle show that that could happen and there would be nothing about the xenograft that would prevent the allograft from working. Now, why did they do that though? Because as you said, Cara, they're, they're first looking at this as a bridge, not as the final transplant. So if you could get this to work so that on average, you know, the recipient of this genetically modified xenograft, the pig heart can survive for three or four years, then that that's your bridge. That gives you time to be on your waiting list for a permanent human heart for three to four years without having to, without requiring the LVAD right, which is basically a mechanical mechanical heart. It's a left ventricular assisted device. It's not a completely mechanical heart. It it just helps pump blood through your own ventricle. And some people have to be like in the hospital the whole time they have it like in the hospital for.

C: Months.

S: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. Yeah, it's not great. And there's another population where this might be especially useful, and that is the pediatric population, especially infants. So some infants are born with congenitally bad hearts that need to be replaced, like they're incompatible with life kind of hearts, like a single vet, they have a single ventricle. And those don't make a good connection to the mechanical hearts that we have and don't work well with LVAD. And so a lot of these infants die while they're on the waiting list for a transplant because because infant hearts are in really short supply, right? So the, this may be the first thing that they go for is to do a pig heart, a genetically modified pig heart as a bridge heart for an infant while they're on the waiting list for a donated human heart. Of course, the ultimate goal is to make these so good that it can be your permanent forever heart or organ or any organ like you just we're just growing and harvesting organs that are, you know, as good as allograft, don't you know, transplants and maybe even eventually better. Now, the the company that did this recent study, they did 10 genetic modifications, just 10 minute modifications. That's not a lot. But what happens when we figure out 20 or 50 or 100 modifications that we can do that will essentially eliminate any rejection? So in the ideal world, the ultimate expression of this technology is genetically modified animals like pigs, that from which we can harvest organs that where there's 0 rejection and they survive for the lifetime of the recipient. And then we just have essentially an unlimited supply as much as we need of, you know, of any of those organs to donate without having to do cadaveric donation or somebody donating a kidney or whatever and having to do any of that without having to do any bridging maneuvers. Just we can just say, Oh yeah, we'll just grow your heart. Here you go. So and the I don't know if we can get to that with a generic, you know, pig xenograft, or if in order to get that good, if you would have to basically give it the recipients immune system. You know what I mean? Yeah, where you have to raise the pig for them. But that's totally plausible, right? You know, or at the very, or at the very least we might have subdivisions right, to the, the, the where it's like basically there are people fall into different groups in terms of their immune system markers. And we could say, or you know, if you're, you have like 1 of 10 immune types, we're going to give you a donation from a pig that's in your type, even though it may not be individual to you as a specific person. It's like blood type. You could think about it that way. We're going to give you a pig that has your type, your blood type, your immune type, you know, and that will be better than just like a generic human pig. It's not just humanized, it's specific to a subtype, and then maybe eventually specific to an actual individual person.

C: Yeah, I could see getting there. I mean, I we.

S: Could absolutely get there.

C: I know it's different, but things like car T therapy, you know, car T cell, like where would take the information from us and then we modify it and put it right back in US, like modify it, put it in the pig.

S: The thing is, we can do it. We can use CRISPR or whatever to genetically modify these genomes. We can clone them and we can raise viable animals. We can harvest their organs, we can transplant them, and they work. The whole thing from soup to nuts works. It's just a matter of getting incrementally better at this point. And the next step they're going to do, they're applying to the FDA for permission to do human trials. So that's the next step. So we could be, I know we, this is the joke on the show. We could be 5 to 10 years away from this being in the clinic from actual patients receiving pig xenografts from this technique. That's way closer, decades closer than any of the other techniques. The other techniques may not even ever pan out. But this is happening now, at least in the at the animal level and human research is, is, is coming up. That's the next step. So we will, we will, we may see this in our lifetime. You know, people start to receive pigs xenographs.

C: So how different are pig? You know, obviously we talk about rejection being an issue like a like an immune issue, but how different is the physical organ? Like are the all the connections really easy or do we have to modify things?

S: There's a reason why they chose a pig. It's very similar, just happens to be very similar to the human. And so their their hearts are are good. They make their mechanically a good fit for a human and we know how to genetically modify them to make them smaller. So they're a human sized.

C: Yeah. I wasn't sure if like because we are bipedal and pigs are quadrupedal like sometimes that affects the orientation of like vessels and and things like that. But I guess.

S: Yeah, as long as the hookups are close enough that you could surgically connect.

C: Kind of bend them.

S: Yeah, yeah. So it's, it's plug and play basically. And of course of a living organ is better than like a mechanical heart in that it's more physiologically responsive, like moment to moment to the demands of blood flow to the lungs into the body. Right.

C: And potentially more resilient, yeah.

S: And gentler on the blood. The biggest limitation with mechanical hearts is that they're very destructive to blood cells. You know, first of all, you got to give blood thinners so they don't clot. And then, you know, people, their, their blood cells don't survive as long when they're being pushed around by a mechanical heart. Now, again, that technology may advance to the point where it gets as good as a human heart. And that'd be great. Of course that, you know, it's going to be a lot harder to do that for other organs, but we don't know. I don't know how far away we are from that. That's a very, very tough nut to crack. Again, I think this is the best. This is the best way to go.

C: Yeah, and even we've got to remember that even if you're lucky enough to get a human heart, you are on anti rejection medication for the rest of your life.

S: Yeah, imagine if you can make this so good that there's no rejection. You don't have to be suppressive drugs.

E: That's the holy. Grail.

S: That's the Holy Grail again. That's the ultimate expression of this. It's a new heart. No rejection, no drugs. Have a nice day. You know, That's it. And yeah, we, and again, we're just incrementally away from that. We just have to keep making advancements. But it the whole, it works. Every we all, all the pieces are in play. So very exciting. All right, Evan, give us an update on chiropractic and stroke, something we've talked about a few times in the past.

Chiropractic Stroke (56:25)

E: We have and it has come up again in a recent article, but I want to ask you all a couple of things. But I want to what I want. Let's see how much we all remember about chiropractic. Steve, maybe you should give others a chance to answer through these before you. I know you've written quite a bit over the years about the history of chiropractic. Yeah. OK. But for the other rogues, what? When do you think it started? What year was the practice invented?

B: Of oh of chiropractic, 1920.

E: Okay.

C: Maybe that's true 1840.

B: 1885.

E: Oh, you're close, Bob.

B: 1850s.

E: 1895 Bob, Good job. And who is credited with its invention? What's the name?

B: Of the that punk.

J: Dude, Doctor Chiropractic.

E: Doctor Punk.

S: Can I say it now?

E: You can, Steve.

B: Dee Dee Palmer.

E: Dee Dee Palmer Palmer.

S: Yep, Yep, yo Dee Dee.

B: His first in my memory banks.

E: His first patient had an ailment that was said to be cured by his chiropractic procedure. What was that ailment?

B: Did.

C: It have deafness bones.

E: Yes, deafness. Hearing loss.

C: Deafness.

E: That's right.

C: Come on.

E: And do we know the what the word chiropractic is or from what what words you put together to make chiropractic?

S: Cairo is hand.

E: Yes, Hand. Hand manipulation like. Practice, practice, right? And practicos. Yes, done by hand. And finally, the idea that misalignments of the vertebrae called subluxations can interfere with the nervous system and cause a wide range of health problems beyond back or neck pain is basically what Palmer came up with. So that's the origin and that's the history. Just a little back story for you guys. Now. New Yorker magazine recently put out a article on their health section in which the headline reads Instagram has made chiropractic neck adjustments more appealing than ever before. But physicians say the maneuver is dangerous. This is not some, this is not new news, OK to us and, and many people in this audience. The author of this article, her name is Katie Arnold Ratliff. She's a freelance writer and editor for their health section. Here are the relevant parts of this article. Last fall, a tweet by Los Angeles cardiologist Danielle Balardo, MD, illustrates the stakes involved with chiropractic manipulation and strokes. Quote Here's the tweet from that doctor, heartbroken after seeing a young patient with no medical history end up with a BIFL grade 2 dissection of the vertebral artery and subsequent acute pika pica infarct immediately after a neck adjustment from the chiropractor. This has to stop. Chiropractors, you have to stop in caps. So what does that mean? Yeah, and neck adjustment caused a tear in the tissue lining of the patient's vertebral artery, which is known as a vertebral artery dissection. And the tear impacted their blood flow so severely that it cut off a portion of their brain from oxygen. Immediately that that patient experienced vision changes, difficulty walking and started to develop weakness on one side of her body. And the person who had their neck, this person had their neck adjusted and then they what had a stroke.

S: Yeah, it's a, it's a lateral medullary stroke and it's like a brain stem stroke. It's pretty severe.

E: Pretty severe. I don't recall us speaking about this particular case before. It was also written about in Women's Health magazine. This was back in November of 2024. They covered it. They went on to say in that article they indicate that this was the fourth time in Doctor Belardo's career. She's the cardiologist where one of her patients suffered a stroke due to chiropractic manipulation. Doctor Bilardo says she wished she had spoken up sooner after seeing the first patient with this condition. She feels guilty for not having alerted people to this health problem sooner. Now her tweet, Doctor Bilardo tweet has been shared almost 6,000,000 times and then we can think, OK, that's good. Her post has been shared quite a bit and hopefully made many more people aware of the risk. However, we have Instagram and we have TikTok and other social media platforms. That is an ocean in which chiropractors and their patients share videos and experience on all the joys and wonderfulness of chiropractic. No mention whatsoever of this particular risk or any other risks associated with chiropractic. Now, I don't have the numbers to share. I tried looking it up to try to quantify, but it's that's almost impossible. But a cursory search for chiropractic on these sites opens up the floodgates so much so to the point that, you know, even a respected cardiologist warning people the dangers of stroke via chiropractic. And with 6 million views, that really doesn't even hold a candle to those who are promoting the practice. Back to The New Yorker magazine article. We have a local connection here inside of that article for us, the SGU right here in our home state, Connecticut University of Bridgeport. Oh my gosh, how long have we been talking about the University of Bridgeport? Even before we were skeptics. Guide to the Universe when We were skeptic When We Were the Connecticut Skeptical Society. Basically 30 years. Yeah, exactly. I know 30 years of that as well. We've been skeptical activists for like half of our lives. It's amazing to think of that. The University of Bridgeport, Yeah, mainly since 19, since the 1980's, the which is when the university was basically bought out by or taken control of by the Unification Church. Doctor Sung Young Moon, the Moonies, they own, they operated the university right up through 2019. I didn't realize they were still involved that late into it, but 2019. We are very familiar with the antics in pseudoscience and cult like atmosphere that has permeated the University of Bridgeport now for decades. Well, in any case, they quote in that article Gentleman James Lehman, a chiropractic orthopedist and the director of the Health Scientist Postgraduate Education Department at the University of Bridgeport. He is a neck adjustment defender. Here's what he says. Statistically, if you had 57 chiropractors do 100 cervical manipulations a week for 52 weeks for 20 years, one out of those 57 chiropractors would encounter this particular situation, meaning an arterial dissection and subsequent stroke.

C: That's too many.

E: Well, yeah, that that is too many and it doesn't exactly jive with other research on this. Now the research also is that has been done on this is a bit what spread out. There are studies apparently in which the frequency of this takes place in one in 20,000 events, 11 time out of 20. And then there's another one that I think was like 1 and 2 million. So you have kind of this very large range here. So I imagine that has to do with, you know, the quality of the study and so many other mitigating factors. Really hard to kind of pinpoint exactly. So I'm not even really sure where he is coming up with this particular set of numbers. I imagine he found the most favorable 1 and he just kind of parrots that as he goes along in defense.

S: But as Cara said, so yeah, first of all, yeah, he's probably using the most favorable numbers. And even the the worst numbers are probably an underestimate because chiropractors have no motivation and no incentive to track this. And they so they don't.

US#05: Yeah.

S: So we're basically the only most of the data comes from physicians who are on the receiving end of these of the strokes of the dissections and right. So that's just not a thorough sample and it's probably under counting them. But even still, even if that, even if those numbers were correct, as Cara said, it's too many because medicine is a risk versus benefit game.

C: Correct. That's the benefit.

S: And there's no benefit. So zero benefit, you know, compared to yes, statistically rare. But when they do occur, you're basically causing a stroke and or death to an otherwise young, healthy person. So there's a pretty bad nigga. It's not like you know, a a mild adverse event. This is a a serious, potentially fatal adverse event. None of it's justified if there's no proven benefit there's and which there isn't. There's no proven benefit to chiropractic manipulation of the neck. And let me clarify that because that's a specific thing. It's not any manipulation of the neck. It's not any physical therapy like physical therapists do neck mobilization, for example, right when they're trying to like, you know, if you have like a locked joint in your neck or you have muscle spasm, whatever, that's different. What chiropractors are doing are high velocity, very rapid manipulations of the neck. It's much more violent. It's way more risky.

B: It's rough.

S: Yeah. And it's like a whiplash event. It's exactly. And there's no indication for it. There's no theoretical basis for it, and there's no evidence of any benefit from it. It's just pure risk. Saying that the risk is low is not a defense. It's just an illustration of their ignorance of how clinical medicine.

E: Works and Steve, not only do they say that that they offer these very low, you know, statistics, but they also said that look, how do you know the patient didn't already have some kind of tear in there and just the the manipulation revealed that issue.

C: Don't, which is why you don't go manipulating their necks.

E: Right.

S: That's not a defense because you absolutely should not be manipulating somebody's neck if they have a dissection. So they're basically saying, no, it's not this kind of malpractice. It's just completely other different kind of malpractice. It's not, it's not a defense, right? It is not a defense. But also there are cases, there are plenty of cases where the cause and effect is pretty clear where the person like basically stroked out on the chiropractor's table.

US#05: Yep.

S: You know, so that's just, it's so silly.

C: It's terrifying. And that's only one of so many possible negative outcomes. Right. And it's. A pretty violent one.

E: Right, right. And there does not appear to be either laws or guidance in place in which the chiropractors are supposed to be disclosing this to all of their patients. Basically self regulating. Right. They self regulate. And in fact, the person who wrote this particular article said who didn't, who said, look, I didn't come into this, you know, one way or the other, pro or con. But basically the reason why she said she would not do this is because if she knows about even this very small chance of risk of this stroke, regardless of which statistics you want to use, she would choose to not do it based on that. So if you had more people ahead of time being made aware of this, or it was mandatory to be made aware of this, then you would have people making better decisions about seeing about going to the chiropractor for the specific purpose.

C: There's also like this whole secondary thing which I don't think we've talked about, which is that because chiropractors are not physicians, when something bad does happen, they're not trained in what to do. So like there are situations where there are lower risk outpatient procedures where patients will be working with nurse practitioners or physicians and, you know, sometimes there's a complication, but there's a protocol in place for how to get them to an Ed quickly and for what kind of first aid to do in the meantime. But like a chiropractor isn't trained in how to do that. They don't have those pipelines in place. They.

S: Don't they say they are, but they're it's a lie. They are absolutely not. They do not have the same training that physicians have and they like to pretend that they do. And if those listen, if all chiropractors were doing was like lower back, you know, lower back manipulation for acute uncomplicated lower back strains, like the one thing for which you could say that maybe there's some evidence that it's as good as other things that you can do for lower back strain. But like massage? Yeah, exactly. Or even giving a pamphlet on good back hygiene is just. As effective. You know, in the literature, but whatever, if they were just doing that or if they basically was another Ave. to become like a sports medicine person or whatever, then who cares, right? But it's because they do this sort of thing because they're not science based and they don't really have the same kind of ethical structure that mainstream medicine has. They and right, they don't really self police. Well, there's just so much pseudoscience and crankery and malpractice happening under the umbrella of chiropractic. They just need to just purge themselves of that get rid of subluxation theory. You know, just practice evidence based, you know, whatever chiropractic and then nobody would care. It would be fine, but that's not That's the but they don't, but they.

C: Lest we forget that they do this on animals and children.

E: Children and babies.

C: Babies, Babies.

S: Completely and and it's and it's.

E: Higher risk the.

S: Thing is, it's their fault. It is 100% their fault. So little bit more of a history, less if you go back 120 years. You know, when chiropractic was in early days, there was another similar profession that also believed in manipulation to free up the flow of life energy. But they thought it was flowing through the blood vessels, not the nerves. You know who those were?

C: The blood letters.

S: The blood letters Osteopaths.

C: Oh, osteopaths.

S: Oh wow, Dio's I forgot.

E: That's. The Dio's. That's how they started.

S: And kind. Of they cleaned up their act. Yeah, they got rid of it. After. After medicine, you know, the basically you know, there was a huge shake up where American medicine decided to adopt the standards of European medicine and become very scientifically half of American Medical schools closed down, they merged, the standards were put in place, etcetera, etcetera. Basically, they went to chiropractors and osteopaths and said, well, do you want to join us and become science based and ethical? And the osteopath said yes. And the chiropractor said no. They said, screwed nerds to you. We're going our own way. We don't need your stinking science. And they, so they, they were given the olive branch and they rejected it. And they've had a hostile relationship with, with medicine ever since. But it's all on them. It really is. Whereas D OS are basically MD. They're MD.

US#05: Yes.

S: And we don't care. I practice side by side with D OS. They're basically MD's. It's just, it's not about like competition or whatever. It's just about, you know, what they do? It's about being legitimate. And this is one of the reasons if they, you know, there's no way physicians would get away with this. A procedure that's doesn't have a proven efficacy that occasionally strokes people's out and kills them? Forget about it, right?

C: It's insanity.

S: It's insanity. All right, let's move on before I have an aneurysm.

Breathable Algae Drug Delivery (1:11:22)

S: Oh my gosh, Bob, tell us about this breathable drug delivery system.

B: All right, all right guys, so researchers have developed a non invasivement fucked up already. All right guys, researchers have developed a non invasive treatment for respiratory diseases that use, get this, an inhalable form of green algae. How does this work? Why do we even need such a thing? So you can read about it in nature communications. The title of the paper is Inhalable by a Hybrid Micro Robots, A non invasive approach for lung treatment. OK, now we know respiratory diseases are on the rise. Scientists are increasingly looking for ways to treat ailments like pneumonia, asthma, tuberculosis, COPD. So part of the problem is that the lungs, even though they're inside us, they're potentially at risk with every breath we take from pollutants, viruses, bacteria, irritants, on and on. You know, they are inside us, but they have such a Direct Line with everything you breathe in. It's like it makes them almost uniquely vulnerable compared to other or, you know, internal organs that we have. The evolutionary development of lungs has actually done an impressive job protecting that that pathway to our lungs. So tell me, how do you, how do you, what do you guys think? What are some of the, the ways that the lungs protect itself from anything getting in? What's what's going on in the?

S: Body, we have a lot of ciliary things that you know, that cilia that constantly moving stuff out of the lungs. You can cough to to phlegm, expel things from your lungs.