SGU Episode 970

| This episode was transcribed by the Google Web Speech API Demonstration (or another automatic method) and therefore will require careful proof-reading. |

| This is a transcript of a recent episode and it is not finished. Please help us finish it! Add a Transcribing template to the top of this transcript before you start so that we don't duplicate your efforts. |

| This episode needs: transcription, formatting, links, 'Today I Learned' list, categories, segment redirects. Please help out by contributing! |

How to Contribute |

You can use this outline to help structure the transcription. Click "Edit" above to begin.

| SGU Episode 970 |

|---|

| February 10th 2024 |

"Obelisks comprise a class of diverse RNAs that have colonized and gone unnoticed in human and global microbiomes." [1] |

| Skeptical Rogues |

| S: Steven Novella |

B: Bob Novella |

C: Cara Santa Maria |

J: Jay Novella |

E: Evan Bernstein |

| Quote of the Week |

I don't wish to be without my brains, tho' they doubtless interfere with a blind faith, which would be very comfortable. |

Ada Lovelace, English mathematician and writer |

| Links |

| Download Podcast |

| Show Notes |

| Forum Discussion |

Introduction, Eclipse 2024 planning[edit]

Voice-over: You're listening to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe, your escape to reality.

S: Hello and welcome to the Skeptics' Guide to the Universe. Today is Wednesday, February 7th, 2024, and this is your host, Steven Novella. Joining me this week are Bob Novella...

B: Hey, everybody!

S: Cara Santa Maria...

C: Howdy.

S: Jay Novella...

J: Hey guys.

S: ...and Evan Bernstein.

E: Good evening folks!

S: So, guys, we're getting closer to the eclipse.

C: Yes, we are.

J: Very close. I know. I can feel the power.

S: I ordered the eclipse glasses for everyone, and I also got the solar binoculars.

C: Nice. I have a pair of solar binoculars and a solar telescope, so I'll make sure to pack those and bring them as well.

S: I checked it out already. Then I let Bob and Jay take a look through it as well. It's funny because if you're doing anything other than looking directly at the sun, it's just black.

E: Right. Yeah, it's like a muddy mess.

B: So you'll use them twice in your life.

J: It's very cool.

C: Well, you can look at the sun anytime, though.

S: Yeah, you can look at the sun anytime, Bob. So we actually looked at the sun, and you can see sunspots. It's cool.

C: Yeah, you actually don't want to use those during totality.

S: Right.

C: You can just look up. You want to use them right before and right after totality.

J: So, Steve, I might just get myself a pair of, like, the plastic solar eclipse glasses.

S: That's what I got. I got 12 pairs of plastic solar eclipse glasses. Oh, the good ones.

J: You got the good ones. All right. Will those fit the kids or no? Yeah, a little gaffer's tape.

E: Yeah, we're good.

C: Yeah, we'll make them work.

E: Oh, and by the way, a little tip. If you think you're going to use – if you have those kinds of plastic glasses and you had them at the last eclipse like in 2017, don't use them because the material does degrade over time and doesn't offer the same protection that they do when they were manufactured.

J: That's good to know. A while ago.

E: Yep.

C: Really? All of them or just the cheapy ones?

E: It's the cheap ones, right?

J: Oh, okay.

S: Don't use expired cheap solar glasses.

B: Right.

C: Yeah. Good to know.

J: So is the main thing here that they need to be polarized? Is that it?

S: I don't think it's just polarized. It's like heavily filtered.

C: No, it's like they're the super... I mean, think about... They're basically the same as the binoculars you looked through. Yeah. It's exactly the same. It's the exact same thing.

S: Except the binoculars are magnified. Otherwise, it looks exactly the same.

C: It's just black.

J: So you know what I found out? So we've been looking for a location, right? And I called up a whole bunch of parks that were on the – what do you call it? The totality line, guys?

E: Yep. Centerline, totality.

J: Yeah, that centerline means like that'll be where the eclipse lasts the longest.

S: Yes.

J: And guess what? My God. So this one park I talked to that normally has like 100 parking spaces said that they are expecting 200,000 people. That's crazy.

C: Yeah.

J: It's crazy. She said that the highway is going to be completely stopped. She said most people that attempt to go to the park won't reach it. That's how bad it's going to be. So two things here.

B: How do they know?

J: Because they have people that estimate these things.

C: They're city planners.

J: Yeah, city planners. Yeah. One thing is if you're going to be viewing it anywhere, wherever you are, I guess it's all happening along the United States.

S: Don't plan on driving anywhere.

J: Yeah. You got to be very careful of the location that you pick.

E: Get to your location at a time.

C: Or go the night before if you can. Yeah. Go camping or something.

S: Or super early in the morning. Yeah.

C: Yeah.

J: Yeah, and if you are coming to one of our shows or you live in that area and you have a place, a cool place to go to view and you wouldn't mind us joining you, let us know because we are looking for a location that's really like right on the center line. If not, we have a backup, but if anyone just happens to have a place.

S: Yeah, we're okay, but if somebody has a great property and wants to hang with us.

C: Yeah, to be clear, we don't mean like you know what bar you're going to hang out at. We mean like if you own land or if you've got wide open space in kind of the Dallas area, preferably southeast of Dallas.

E: And if you can tolerate us.

C: Right, yeah. If you want to hang out with us.

E: We're a bit insufferable.

S: We're kind of obnoxious, yeah.

C: And it's not just us either. It's us and our loved ones.

S: And our family. But it's still what? It's going to be like, whatever, 12 people.

J: Yeah. It's a crew.

C: Yeah, it's a crew.

J: George won't be with us because he's going to be playing music with Brian Brushwood, I believe.

C: Oh, really? Oh. He's going to be playing music during the eclipse?

J: I think so, yeah.

C: Huh. That's cool.

J: That's a very George thing.

E: I wonder what songs he'll be playing.

J: Yeah, that is a very George thing. Yeah, so while we're talking about it, so we have an extravaganza happening in Dallas on April 6th. And if you're interested, you can go to the SGU homepage. There's a button on there. Tickets are selling really fast on that. We're super excited. We have already had a sold out private show. So the only tickets that are available left are for the extravaganza. That's an hour and a half plus show. It's a stage show. There's a lot of improv comedy bits that we do. And it also has a very, very strong backbone of science where we teach you exactly why you cannot trust your senses.

S: Your brain.

J: Your brain. Your brain is a liar. Is a liar. It lies to you every day.

E: Oh, I still love it, though.

J: But it's a ton of fun.

S: And here's the other thing. So the private show plus is sold out, completely sold out. But we're getting a lot of people who missed it and are asking if there's other options. So we're exploring. No promises, but we are exploring options. But why don't we do this? If you will 100% buy a ticket to a private show, if we somehow make more seats available... Email us and let us know. Basically, you're agreeing to pre-buy the ticket. Because only if enough people do that? will we do what we need to do to make more seats available.

C: You know what I mean? And when would it be? Because a lot of people can't agree to something.

J: That's on the 7th.

S: Either way, whatever happens would be on that Sunday.

J: We have not picked a time yet because some parameters are in flux right now. But email us at info at theskepticsguide.org. The subject should be private show. That will make it easy for me to find it. Yeah, and email us. I mean if enough people do it, then I will ramp up my efforts to try to find a bigger venue.

E: Yeah. Yeah.

S: All right, Cara, you're going to start us off with what's the word?

What's the Word? (6:14)[edit]

C: Yeah, so I got a request or a recommendation from William in Louisiana that he recommends the word cardinality. And then the next sentence, this word has nothing to do with birds. Sorry, but I did try to think of something in my field of database design and architecture. Cardinality has applicable definitions in database technology, mathematics, music, and all use the word to describe the number of unique values in a set. Also, some data engines have a process or feature called a cardinality estimator that quickly assesses the number of distinct values in data in order to properly join or query the data. The definitions of the words in Mathematica Music seem similar, but their vagaries are beyond me.". So, I will first and foremost say thank you for the recommendation. And also, William, you say that this has nothing to do with birds, but it actually sort of does, by way of the clergy, at least. So we want to start by looking at the root word, which is cardinal. And oftentimes when you look at the definition of the root word, the first definition is the ecclesiastical definition. So that's an official of the Roman Catholic Church, ranks below the Pope, and is appointed by him to assist him as a member of the College of Cardinals. Then you'll usually see... the cardinal number. And then from the color, you'll see the cardinal bird, which is a bird that we have in the US and Canada and also in Mexico down to Belize, which is like a red bird. Oh, I didn't realize it's only red in the male completely. They have black faces and red bills in both sexes, but it's nearly completely red in the male sex. A lot of other birds of the in South America and the West Indies that may be called cardinals as well. So you'll see sort of very often when you look at the order of definitions that there is a temporality to those orders. And almost across the board, every dictionary I looked at started with the Roman Catholic definition first and then moved on to the birds definition. So I was like, okay, before we get to the science, I want to get to the bottom of the etymology. And I realized that the word cardinal or actually starting with the word cardinality, which comes from cardinal because that was the recommendation. If we go back to the word cardinal, in early 12th century, 12th century is when we first saw it coined from medieval Latin. The North American songbird was named all the way in the 1670s and it was named for its red color resembling the cardinals in their red robes. So cardinality is related and it comes from that red color, but it was actually the religious term. So cardinal is a noun. You'll also see cardinal as an adjective, and that came in between the two. So the adjective, which comes from the Latin noun, is actually referring to something as chief or pivotal or principal or essential. And it does seem to come from an original term, cardo, which actually means pertaining to a hinge. So it's something on which something turns or depends. It hinges on it. And that's where we start to see all of these other definitions take place. So remember cardinal as a noun, cardinal as an adjective, and then cardinality as a noun comes much later. 1935 is the mathematical sense of, Prior to that in the 1520s is when we saw the condition of being a cardinal. So cardinality would only refer to the religious sense back then. But in 1935 is when we started seeing it in mathematics and after that in a religious sense. So what does it mean in mathematics? Well, as our friend William did mention, it refers to the number of values in a set. So from what we understand is that first we're seeing cardinal being used as an adjective. So first it's the noun referring to religion, and then we're seeing it used as an adjective, again, hinging things that things rotate around or rely upon. So cardinal numbers, cardinal directions, that was a term that we saw pretty early on. And that's because those were the fundamental numbers or the fundamental directions that. And then after that, we saw a mathematical term that refers to the number of different things in a set. So it's the measure of those different elements. And then you also see the same thing in music, right? The cardinality of a musical set is the number of pitch classes that are within that set. And then as you see it used in sort of computer science, data modeling, database design, it's all based on that fundamental definition of uniqueness or of something fundamental that other things hinge upon. And so the word did evolve as the different fields required the usage of it. But really, they do come back to not the bird, but to the robes for which the bird was named.

S: Yeah, it's a neat pathway for that word. You wouldn't have guessed that that was the first thing.

C: Right. You would have thought the bird came first.

S: I don't know that I would have assumed that because then you have to think, well, where did that bird name come from? Unless it was a guy. Usually birds, they're named after the person who discovered them or named them or they're named after some feature of the bird themselves.

C: So they are named for the redness. But yeah, where did that red come from?

S: Where did that come from?

C: Yeah. Interesting.

News Items[edit]

S:

B:

C:

J:

E:

(laughs) (laughter) (applause) [inaudible]

New Class of Microbes Found (12:01)[edit]

B:...could be meatballs...

S: All right. Thank you, Cara. Yep. All right, Bob. I understand that scientists have discovered an entirely new type of life, sort of.

B: Not really.

S: Not really.

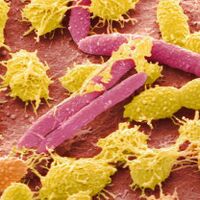

B: But it's still fascinating. This is a new type of – let's put it this way. A new type of biological replicating agent has been found.

C: So like a virus?

B: A cousin to viruses, if you will. They're being called obelisks. And they've been found in people's mouths and guts.

E: Not mine.

B: How worried should you be? Not at all. And what are obelisks? So this paper is from a team at Stanford University. It's a preprint on the bioarchive server called Viroid-Like Colonists of Human Microbiomes.

J: Viroid? Viroid. Yes. Oh, yeah.

B: You're going to hear about vibroids. So this isn't the first time that they've been written about. Obelisks have been already widely written about, including in the two juggernaut journals, Nature and Science. So to understand obelisks better, we need to compare them to the other similar biological doodads out there. The first comparison doodad recently held the world hostage. For a few years, SARS-CoV-2. These are, of course, the mighty viruses. They're really awesome little buggers, really, from a dispassionate Vulcan-like perspective. Viruses are infectious acellular microbes, essentially. By acellular, I mean there's no cytoplasm or cellular organelles. There's no native metabolism there. They're just DNA or RNA surrounded by a protein coat called a capsid. No way! Yeah. Oh, nice use, Bob. One followed by 31 zeros. That's a little bit easier to get your head around, a million trillion trillion.

E: Here, Avogadro, hold my beer.

J: There's a lot.

B: Jay, I do this with numbers. You know it. You've been doing it for almost – Don't you love those? I love big numbers.

E: Oh, they're awesome.

B: All right. So those are viruses. Next are viroids, V-I-R-O-I-D-S, viroids. These are subviral. They're even tinier than viruses. A couple hundred base pairs, I think. Just little snippets of circular RNA. There's no protein shell. So because they don't have that shell, they don't have like the code, if you will, to break and enter a cell. It's a healthy cell. So they typically enter cells, plant cells generally but not exclusively, that are already damaged and typically already damaged by insects. That's how they get in and wreak some havoc. Also, huge point, viroids cannot make proteins. They cannot make proteins. That's a huge distinction right there. So then now we have the obelisks, these new obelisks that have been discovered. So these are like viroids. They have circular RNA but no protein shell. But like a virus – Obelisks can code for proteins. They only have a couple of genes, but they can code for proteins. So they're kind of like mysterious hybrids, right? Part virus, part viroid.

C: Can I ask you a quick question, Bob? Yeah. How is a viroid different than just free-floating RNA?

B: They can cleave and reattach their segments.

C: Oh, okay. So they have some control over the genetic material.

B: Yeah, like they're kind of – they have some capability.

C: Like some molecular scissor in there somewhere.

B: They can cleave themselves apart and put them back together, which I think is something that's fairly novel for just bare RNA. So what has this team discovered about these new obelisks? Well, they've used apparently very innovative computational biology techniques. They searched through 5.4 million datasets of these publicly published genetic sequences, and they identified 30,000 different types of obelisks. Now, 7% of the human gut data sets had these obelisks and a whopping 50% of the human mouth data sets had them. So essentially, flip a coin, you probably have some obelisks in your mouth right now. They show that a lot of these obelisks or really all of them, you could have them if you do have them for up to a year. They've identified people having them for up to a year at a time.

C: The same ones?

B: Yeah. Oh, wow. In addition, different areas of your body show different types of obelisks. So they're kind of all over. Here's a quote from the preprint. They said, obelisks comprise a class of diverse RNAs that have colonized and gone unnoticed in human and global microbiomes. They were really just hiding kind of in plain sight, and it took these slick computational biology techniques to kind of pull them out of these data sets, and they weren't really noticed. So one type of obelisk that they identified using as a host a specific type of bacteria, it's a streptococcus sanguinus, and that's a host that's found in the mouth. But for the rest of these obelisk types, we have essentially no idea what the host is. It's probably bacterial, but it could also be archaeal. It could be fungal. It could be meatballs. We're not sure. We're not sure. But bacteria for sure because we already identified one probably, but they think that fungal hosts are also likely as well. Now, I said that obelisks code for a protein, and that protein is being called oblin, O-B-L-I-N. Now, this is a protein that is not homologous to any known protein, meaning it has no evolutionary similarity to them. It's like here's a brand new protein, never seen before, and not really related to any other protein that they've ever encountered. They don't know what it does. It's probably related to some kind of reproduction. But they really aren't sure. So yeah, so there's tons of unanswered questions about obelisks and future research. We'll certainly try to answer them. Apparently, this is really a hot topic. They're going to find out things or they're going to investigate things like what does this protein oblin do? And one of the big questions is, What effects do obelisks have on our health, if any, right? We have no idea. If it's detrimental, if it's helpful, I could imagine if it's actually – it helps us in a way or if it does absolutely nothing, just kind of like this stealth little RNA that's been around and is everywhere but just doesn't really do anything bad at all for us or anything at all.

E: Are there other examples of things like that that exist in our biome?

B: Not like obelisks. This is something that's discrete and like I said, it's kind of a hybrid between those two others that are near that scale, the viruses and the viroids. But it's different. It's got characteristics of both, which makes it really unusual. So most fascinating that I found is studying the obelisks could actually help elucidate the origins of life on Earth. This is really fascinating because if they could tease out this relationship, if any, between obelisks and viruses to these viroids, it could help confirm or refute what's called the RNA world hypothesis, which we haven't – I don't think we've discussed it too often at all on the show. The RNA world hypothesis describes the earliest – And the most mysterious part of evolution, right, the start of life, or as I like to refer to it, the transition from chemistry to biology. And if this hypothesis, this RNA world hypothesis, if it's correct, it started as self-replicating RNA, which is what a viral is, right? It's essentially… self-replicating RNA, and before DNA or proteins ever existed. So if that hypothesis is correct, potentially obelisks and their relationship to viruses and viroids especially could actually help us finally figure out one of the more likely ways that life could have started. Did it start with self-replicating RNA? Obelisks could actually help us determine if that was the case, if that would be Obviously, probably multiple Nobel Prizes right there if that happens. But I'll definitely be tracking this. Interesting stuff.

S: Yeah, it's neat. So it's neat to think about. like RNA, DNA, like genetic material is a thing unto itself. Like it doesn't – it isn't quite life but it is lifelike in that it can replicate – Little organic machines. Yeah.

B: It's understandable why it's difficult to determine if these things are alive because it has some qualities of life and some qualities that aren't alive. Clearly, we associate with life. So that's why it's not an easy thing. I think most – generally, they're most often considered to be not alive. But it's definitely in this gray zone and it depends on definitions, right? It depends how you want to define it. Steve, initially when you listed my topic, you described it as a new microbe. And even that's problematic because it depends how you define microbe. Microbe will mean things – will include things like having cells, which this doesn't have. Microbes are also infectious as well, which is why viruses – which aren't cell-based at all, are considered to be microbes. But obelisks aren't necessarily infectious at all either. But that's kind of undetermined. So even calling them microbes might not even be accurate.

S: Categories are fuzzy. And if we evolved – if, again, life evolved from non-life, chemistry into life, you would expect there to be things at the cusp that are – Fuzzy.

C: Yeah.

S: That don't quite fit. That makes sense. All right. Thanks, Bob. All right, Jay, tell us about this new Slim Lunar Lander.

SLIM Lunar Tech (22:08)[edit]

J: This is a Japanese lander. This is a significant achievement. The system is called the Smart Lander for Investigating the Moon. So that's, you know, S-L-I-M. I like it. I, for some reason, thought it was actually like this slim-looking, kind of svelte-looking lander. That's not it. They successfully landed on the moon's surface on January 20th, 2024. So why is this significant? Well, first of all, they landed successfully on the moon. This is not an easy thing to do. They are the fifth country to achieve a lunar landing. That's a big deal. And this is also a technical milestone in space exploration. So despite encountering a power issue along the way with their solar cells, it did limit their operational time. SLIM's landing is considered a crucial step forward because it used an advanced precision landing technology. And boy, do we need that? because it's very tricky to land on the moon. What they'll end up doing is if the technology ends up being really useful, which it seems like it is, it's going to offer the potential for future spacecraft to basically land in challenging terrains on the moon and specifically targeting resource-rich areas in the lunar south pole, which could be very irregular and not level. Slim landed within a 100-meter zone that was selected ahead of time. So that's a big deal. It might sound like a huge space, and it is a big space, but it's much, much more narrow than all the other times anybody has ever landed on the moon. as far as them picking a landing site. Like you can't just pick a spot and get there very easily. It's very complicated.

B: It's often as big as – like it's measured in like kilometers, right, Jay? Yeah.

J: Yeah, yeah. I mean, when you look at the first moon landing, they were not even close. I mean, they were basically like freewheeling it at the very last seven seconds, but they had no idea where they were going to land.

E: That thing landed at all is half a miracle.

J: It is. I completely agree. So this is a significant improvement in landing accuracy over all the previous missions that have taken place. All previous landings required a much larger clearing. They pick a huge, relatively flat area, and they're like, anywhere in there would be great. Good luck. Let's try to land there. So this was achieved through a vision-based navigation system that they created. And what it did was it compared real-time images of the lunar surface with pre-existing lunar maps. And that was the way that it was able to know where it was, basically using legitimate satellite navigation, right, in essence, without the pinging. It was comparing the maps so it knew where it was at any given moment, comparing it to the existing maps, and they were able to bring it down later. Pretty accurately. It's very impressive. SLIM also deployed two small rovers, and both of these rovers were equipped with a lot of cool new technology for lunar exploration. So the first one, the Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1, this one has a camera. It has several scientific instruments on there built in. It also has a unique way to move on the moon. Guess what it does, guys? It hops.

S: Really?

J: It actually hops.

S: It's a hopper?

J: And it's pretty cool if you think about it because that was the way that the astronauts figured out is the most efficient way to move around on the moon. Not walking, but basically taking little hops. So this technology is particularly useful for navigating uneven and rocky terrain on the moon's regolith. I think it's genius. So this allows the vehicle to overcome obstacles that are in its way, perform in-depth investigations of specific lunar features, which is awesome. So Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 also can do something called direct communication, right? So it can do direct communication with ground stations, including inter-robot test radio wave data transmission. I love that. So it can communicate with the other lander. The other lander is called the Lunar Excursion Vehicle 2. This lander is a collaborative effort among government, industry, and academia, and it showcases new mobility concepts by rolling on the surface. So if you're paying attention, they are experimenting with different new technologies, novel technologies, and experimenting with different ways of mobility on the moon. Why? Well, because we're all planning on going there, right? Right. And luckily, the United States has a wonderful relationship with Japan. And we will be working with them. The United States will be working closely with Japan. And they already are working with NASA. But it's just a great thing because we have different countries and companies, private companies. They're all building new technology and pushing, pushing, pushing to get it to where we could actually start really getting to the moon and putting infrastructure there. Yeah. Now, all these technologies, again, they're not tested. They will and are being tested on the moon, and that's where they're going to show if they have their metal to make it to more legitimate missions. So the success of SLIM is showing that Japan has similar level of technology as the other leading countries that are out there. It's also from a geopolitical perspective. It's important because we have a lot of countries now that are all trying to get to the moon. We've got the United States. We've got China. We've got India. We've got Japan. All sending missions to the moon, sending big missions into orbit. Now, my hope is that we join forces and just start to co-op with each other extensively. Later on down the road, you know, countries are working together now, but not to the degree that I think they should be in order to really get a full-time presence on the moon. There's been a series of lunar missions by various nations, countries, entities, whatever you want to call them, companies. including India's recent landing. It was a failed attempt by a U.S. company recently that I covered, and also unsuccessful efforts by Russia and iSpace in 2023. So there's a lot of missions going up. We're seeing failures. It's very complicated. Like Evan said, it's damn near miraculous when we could do this. The level of science and engineering and all sorts of – like textiles, everything. There's so much that goes into this stuff. The planning, all the safety measures that they put in, getting data back from the crafts that we send there. It's incredibly complicated. It's super expensive. So in partnership with the U.S., Japan's aerospace exploration agency called JAXA, or just J-A-X-A, it's contributing to the Artemis mission right now by developing a pressurized lunar rover. So pressurized meaning that astronauts would go into it and possibly take off their spacesuits while they're driving around on the surface of the moon. Very cool. So JAXA was established on October 1st, 2003, which surprised me. I thought that they would have had a space agency that predated that. But that's essentially when it started. It was pretty cool. It's a cool backstory. You should read about it. They combined three different companies. Basically, they turned that into their space effort, right? It's pretty cool. I'm really happy to hear that so many countries are doing this because once commerce really starts to happen, once humans basically make outer space be a common thing and industry will happen out there, there'll be a slow expansion of humans not living on Earth, right? And I think as odd as that is, Steve and I just talked today on TikTok about – or recently we talked on TikTok about like what's going to happen to humanity today. In the future, and how are we going to optimize people for space travel? We were saying like there could be bioengineering and stuff like that. I think it's inevitable that humans are going to have a permanent presence in outer space. Just seems to be in our nature. You know, we just aren't stopping. We never stop at borders. We just keep going. I love all this stuff. I think it's wonderful. I think human exploration is important. And I think, you know, it's money well spent.

S: And Jay, just to clarify, this lander is just for equipment and probes, right? It's not designed to have crew.

J: No, this is – yes, it's small. And absolutely, it's there to test technology, to get readings. Again, that landing technology is amazing. And they might be able to sharpen that and even make it more and more accurate. It's the beginning of this new landing technology. So very cool stuff on the way. So I got one other quick thing, guys. Have you heard of NASA's Plankton Aerosol Cloud Ocean Ecosystem? No.

E: Is that an acronym? What's the acronym?

J: It's PACE.

E: Okay.

J: Plankton Aerosol Cloud Ocean Ecosystem. So this is a spacecraft that's scheduled for launch aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida on February 8th. PACE was created to enhance our understanding of the ocean's health. And they're doing this by mapping the color and light of the Earth's oceans. So it's positioned 420 miles above Earth, and PACE will use its three scientific instruments to study clouds, aerosols, and phytoplankton. These are key components that affect ocean color and the health of marine life. So the data we get from PACE will inform us on the ocean's overall biological activity. This is really important, and it's going to Probably give us a ton of information about global warming. Oh, boy. So the mission is expected to last at least three years. And NASA has been studying the world's oceans for over two decades. So this is the latest installment. And, you know, we're focusing on the ocean's biology, you know, air quality, climate indicators. Lots of important information is going to come from this project. And it costs almost a billion dollars. So, like I said, this stuff is not cheap.

C: Any idea how these new cuts are affecting all of these things? I mean, like today, JPL laid off 8% of its workforce.

J: Yeah. I haven't heard anything about what the actual outcome is going to be, like what it's going to do as far as like boots on the ground. But I'm sure it's going to have an impact somewhere.

C: Yeah, like the budget is, it looks like, slashed. Oh, boy.

Misinformation and Wellness Influencers (32:29)[edit]

S: So, guys, are you familiar with wellness influencers?

J: Oh, yeah. I think I know what you're talking about. Those two words together, I hope.

S: I don't like those words individually, and they're worse when you put them.

C: It's sad, too, because I do like the word wellness, but it's been co-opted.

S: The word's gone, Cara. It has been totally co-opted. It's bullshit.

J: It's behind the words.

S: It superficially, yeah, it means anything dealing with being well, with health and not just treating disease but also enhancing health, et cetera. But it's been 100 percent co-opted by pseudoscience for the last – since like the 50s. I mean this is going way back. Yeah, it's a done deal. So I noticed a couple of recent articles where the mainstream media is catching on to the fact that wellness influencers are peddling pseudoscience and misinformation. And they're like shocked, shocked that there's so much misinformation coming from these popular wellness influencers. Whereas we know it's like this is completely 100% expected. Right. But what has been happening that got noticed was that wellness influencers are getting into climate change denial. Huh. Yeah, huh. Why would that happen? And again, superficially, it doesn't make sense because first of all, it has nothing to do with health care. And because usually wellness influencers, part of their narrative, their ideology is to be like a crunchy. nature is always good thing, right? To be pro nature. Yeah. In like a tree hugger sort of way. And this would seem to go against that. But as we understand, wellness influencers are really all about the pseudoscience, which involves being anti-authoritarian or anti-expertise, and utilizing conspiracy theories. And so this just demonstrates, again, what we've been saying for a long time. On science-based medicine, we call this crank magnetism, where if you promote one crank pseudoscientific conspiracy-mongering idea, the chances are pretty good that you are going to promote others. Because there's obviously something systematically wrong with how you evaluate evidence and also you're lacking in certain critical thinking skills, right? And that is going to make you vulnerable to believing and promoting all sorts of nonsense. But in this case, I don't think I'm sort of agnostic towards the gullibility versus cynicism of these people because who knows? They're somewhere along that spectrum. It doesn't really matter. What is happening either way is that the wellness space, right, is promoting a certain narrative. And that narrative isn't about health. It isn't about science. And it isn't really about being respectful of nature, right? What it is about is it is about being anti-authoritarian and conspiratorial in the guise of self-empowerment, right? So they tell people, you can do your own research. You can take control of your own health. Don't listen to what they tell you, right? So that's really the core ideology, the core narrative here. The appeal to nature thing is really incidental. It's not core to what makes them the gurus that they are. It's just one of the marketing ploys that they use. But they can flip it on a dime, right? They're not tied to that because it's not the essence of what they're doing. The essence of what they're doing is don't believe authorities. Don't believe experts. They are lying to you. Just believe us, right? Believe the gurus. We're the only ones that you could believe. And here we're going to empower you with these simplistic explanations for complex problems and buy our products, right?

E: Sadly effective.

S: Well, it's evolved to be effective, right? If the algorithm that's happening here is, well, what maximizes clicks? What maximizes revenue? What maximizes engagement? That's it. And if that's your only algorithm, that's the only feedback loop that you are operating under and you're not operating under. what does the science say? and is this ethical or is this –? have high standards of scholarship or academia or whatever. Does this make sense? If your only thing is do people engage with me and do they give me money, then this is the direction that you'll go in. This is where the evolutionary forces lead you. They lead you to a narrative which maximizes engagement. And what maximizes engagement? In a lot of contexts, it's outrage, right, making people mad and outraged.

E: Scaring people.

S: Making people scared, making them afraid of something. So you create a fear and a solution to that fear, right, at the same time.

C: Making them feel like they have some special power or information that other people are privy to.

S: Making them feel special. Making them feel like they've peeked behind the curtain and they have some special knowledge, some privileged knowledge that most people don't have. Making them feel self-empowered. These are the things that are driving the narrative. And that's really, that's 100% what the wellness phenomenon is about. Everything else is the skin, right? It's the packaging. It's the marketing glitz. But it's not the core of the phenomenon itself. So the fact that wellness influencers are now promoting climate change denial makes 100% sense. This is not off-brand at all.

E: It fits neatly into the template.

S: Of course they are. Of course they are. It's exactly what they do.

C: It's also so sad because it shows how historically, and when I say historically, I mean including up to this moment in time, the wellness industry has preyed on vulnerable people, ethnic minorities, women, people who have struggled to have political or socioeconomic power. It's like you see the, I don't know if anybody's seen that amazing documentary about the sort of pyramid scheme that is Herbalife, but they go into very low income communities and prey on individuals. You see Goop and all of these different, I mean, they prey on women specifically. And yeah, it's because these are people who oftentimes lack empowerment because of societal structures. It's so sad. Yeah.

S: Yeah, you know, absolutely. And we also see it in professions that may historically did not get as much respect as they deserved. And then it becomes a way to like promote themselves, promote their profession. And, you know, like we see this a lot in nursing, for example, like with therapeutic touch. Therapeutic touch is like this is something that nurses do, that only nurses do. And you could do it without the physician. And there's a lot of feminism empowerment in it as well. Which, of course, you know, while everyone on the show, we're all pro-feminism, we're all pro-equality and all that stuff. But the point is they're being exploited. Like these past injustices are then being exploited to like sort of re-exploit the population. A hundred percent.

C: Yeah.

S: It's why it makes it so tragic and so frustrating. There's one, just one example I have to throw out there. So there's a wellness influencer called Truth Crunchy Mama. which is like, oh, like you couldn't make it up.

E: That's like an AI coming up with.

C: Well, yeah, that's what they call themselves now. They call themselves crunchy moms. It's a whole thing.

S: You got the speaking truth to power and they're like, don't believe what they say. You got the appeal to nature crunchiness thing and you got the mama, which is a backhanded swipe at authority and expertise, right? It's like being a mother is all the expertise I need.

E: Yeah, the mommy instinct, the Jenny McCarthy. Jenny McCarthy.

B: I remember that.

S: She definitely pushed that ball forward. So this is just like – just call it what it is. Truth Crunchy Mama. So she says – she was saying about the fires in Hawaii. Right? Oh, yeah, those. Remember that? Stop blaming things on nature that were actually caused by the government. Right? So the government started those fires for their own nefarious purposes. Mercola, who's infamous, you know, Oh, yeah.

E: Joseph McCullough.

S: Just asking questions. Could this be a land grab by the government? They're basically destroying this property so that they could build a smart city. Just going to throw that question out there. What? I'm not making any claims or anything. Yeah, it's the Jewish space laser kind of level of conspiracy mongering. It's like anything that happens, the government did it. It's deliberate. Don't believe anything that they tell you. It's all nefarious, evil cabal trying to take your power and take everything from you. But come to me. I'll buy my supplements and everything will be okay. I think, ironically, one of the people who are, I think, operating in this same space is Alex Jones. Oh, yeah. You may not think that at first. How is Alex Jones a wellness influencer? But he's doing the same thing, just emphasizing different aspects of it. So he's promoting conspiracy theories, outrage, distrust of authority and expertise. And he's selling supplements, right? He's just slightly differently branded. But the formula is identical. It's identical. It is the same thing. He's selling dubious products. He also sells prepper stuff.

C: Yeah, and gold. Yeah, but I mean it's kind of true. And I know that this is going to sound a bit reductive. But like Alex Jones is just like the white man's health influencer.

S: Yeah, right. Hugely. Appealing to a different segment of the population. But it's the same formula, just a slightly different spin on it.

C: Yeah, it's all the same. It's all like you've been – somebody's taken something from you. You're having to work harder to get the same results because of a shift in the economy. And this is how you can get your power back.

E: Yeah. And the reason they all do it is because, sadly, it works. It yields results.

S: Yeah, it works. And it's frustrating and good to see the mainstream media notice. I just wish they would not forget in two days when something else shiny distracts them. You know what I mean? Exactly. Because it's just – this is the story for today. But it's not – they don't consistently realize – because then they'll be promoting their nonsense tomorrow. You know what I mean? Without remembering that, oh, yeah, that's right. They're conspiracy theorists.

C: Well, and I think it also shows a mistake that is often made. And I think we've made that mistake in the past as skeptics and the skeptical community has sort of made it in the past is not seeing the forest for the trees. It's like, let's focus on miracle mineral solution or, you know, whatever. Like, it's just a new iteration of the same problem. Like, yes, it's important to debunk all of these individual things, but it's also important to do exactly what you're doing right now, which is saying you need to see the pattern.

E: We have to have the examples to point to.

C: We do. Of course we do. But like, I think part of the reason that the media moves on so quickly is because they're focusing on the trees and not the forest.

S: Totally. I agree. Yeah, and that's a pitfall we all can fall into.

C: Yeah.

S: But, yeah, I mean, I do think we've made a specific effort to look at the big picture.

C: Yeah, we've got to constantly contextualize these things.

S: Yeah, absolutely.

E: Yeah, our 30 years of work has been this.

C: Yeah.

S: Yeah. And it takes a long time. And we've spoken before. Again, I don't like to bring this up, you know, because I don't want to, like, make it sound like I'm ragging on people. But there have been pop-up skeptics in the past who— who have taken a very superficial approach to this. Like we're just going to debunk claim after claim without, without earning their bones, as they say, right. Without like putting the time into like really understand the phenomenon at, at a more sophisticated level. And again, not to squash any young skeptics or people trying to get involved, but again, like always you have to be a little bit humble and, Skepticism is not easy. It is a very highly developed academic discipline. There's a lot of literature involved. And it took us a long time to get to the point where we start to see these bigger pictures and these commonalities and how it all plays together and how to approach it. And it's all very nuanced. It's always more complicated than you think. So just again, just keep that in mind as you are trying to be activist and participate in this. It's not easy. Don't think because the pseudoscience is silly that you could just jump in there and do it. That's a recipe for getting burned. And we've seen that happen a whole lot.

E: Absolutely. And just because people are educated does not mean that they have those particular skills or subsets. And we see that all the time. I think one of the more recent examples – Is the congressional committee for the UAP phenomenon, the UFO phenomenon? I mean they brought in some really talented scientists in their own fields and stuff. But where are the skeptics? Where are the neurologists who speak about how the human brain is so fallible and tricks us all the time? There's no – those are the elements that are missing from those kinds of efforts.

S: Totally missing and that's why it was also frustrating because there's also, just like in other academic disciplines, there's institutional memory. It's like you need skeptics to say – and we did this talking to each other like in the skeptical literature but it didn't break through to the congressional level. It's like. these are the same claims they've been trotting out for decades, for decades. We've already debunked these 20 times. This is what they're doing. This is why they're wrong. This is why you should not pay attention to this. But we don't want to get into the backstory of those specific meetings because there was a political level to them that has nothing to do with anything we're talking about. So that's I think partly – that was designed to fail in the exact way that it failed in my opinion. But it did fail. And even when they're trying to get to the bottom of a complex issue like this, they get burned because they don't get – they don't recognize that this is a specialty, that understanding pseudoscience and conspiracy thinking is a specialty. As I like to say, we have a particular set of skills. And it is very narrow, you know, but it takes a long time to develop it to the point where you could hear like the test. Like this is why people email. So how do you what do you guys make of this? Like it sounds superficially right. Like, OK, this is how you break this down. It takes you a long time to get to that point.

C: Do you know what's interesting to me, Steve? And I'm curious about your take on this is that oftentimes there's this undercurrent of like anti-authority, right? Sort of like we have special knowledge or we are in like a chosen club. But over and over, they fall back on pseudo scientific sounding things. So like over and over when you start to really dig, dig, dig, who is the final source that everybody's listening to? It's like a Merkula who, yes, he's batshit, but he's a doctor. And I think that's the thing that's so funny to me is that there's always somebody who has authority. And yes, they've taken that authority and really done a disservice.

S: Yeah, they're not internally consistent. Right. Because, again, because the the core phenomenon is like what I've been describing and everything else is flash and sizzle. And right. So you would think, oh, this is all about doing things naturally. No, it isn't. It's about the conspiracy theory. The natural thing is just the brand. It's that's all it is. And they will swap that out for it's the latest science or it's ancient wisdom or this guy's a doctor. It doesn't matter. They just will swap these things out as needed around this core of. don't believe the experts, believe me, buy my supplements.

C: That's why it's so frustrating when you're having a discourse with somebody and then they start trying to cite science and you're like, you're not allowed to do that. You just told me that you're not operating from that framework.

S: Right, right, right.

J: Choose a lane.

Super Earth in Habitable Zone (50:10)[edit]

- NASA announces new 'super-Earth': Exoplanet orbits in 'habitable zone,' is only 137 light-years away[4]

S: All right. Evan, tell us about this new super earth.

C: Super Earth!

E: That has nothing to do with Superman. But yeah, this is neat. TOI-715B. Yep, that's its designation. A super Earth exoplanet that orbits an M-type star, which is a red dwarf star. It has a mass of about three Earths. It only takes roughly 19 days to complete one orbit of its star, so it's pretty close.

S: Which means it's almost certainly tidally locked.

E: And tidally locked, yeah.

S: No, this is not Earth-like. Well, well. Habitable zone or habitable zone.

B: Habitable, habitable.

S: So, Evan, you said it's got three times Earth's mass. Yes. What do you think the surface gravity is? Because I calculated it. Because it's also about...

B: Depends on the diameter.

S: Yeah. So, the diameter... 1.5 of Earth.

E: It's about 1.5 Earth.

S: So, you have three times Earth's mass, 1.5 Earth's diameter. What does that calculate out for surface gravity? What do you think?

E: Is that a six times? Is that a... Is it three times 1.5? 4.5? five or is it?

S: i think you're all over the place? yeah well for the three times the gravity. so it can't be more than three right? um well it could if it was smaller. uh but so it depends on the radius and the mass. so the thing is it's heavier but it's also bigger. so they offset each other a little bit.

E: They aren't launching rockets into space anytime soon. They could.

S: They could. They're under the limit that you would need to be under in order to launch chemical rockets off the surface. Oh, they are under the limit. So I calculated the surface gravity at 12.29 meters per second squared, Earth being 9.8. So that's 1.25 G is the surface gravity. Whereas 1.5 is the limit for chemical rockets being able to get into orbit.

E: Okay. So it's not that big.

S: You think it's three times the mass, but it's only 1.255 G at the surface gravity.

B: Anyway.

E: Nice workout, dude. It's been time now. Yeah, it's in what's called, and this is a new, I must have read this before, but didn't recognize the significance of it. It is considered to be in the conservative habitable zone.

B: Habitable.

E: Habitable. We've talked about the Goldilocks zone or habitable zones of exoplanets and other planets going around their star where you could have, among other things, liquid water. on your surface, potentially an atmosphere among some other things, smaller-sized rocky planets. Okay. But there's also this – so there's this optimistic habitable zone, which is wider, but a conservative habitable zone is more narrow, potentially more – it gives you some more breadth as to the possibilities of there being liquid water among other things going on. But a lot of other things would have to line up for surface water to be present and, of course, having a suitable atmosphere among other things that you're going to look at. But really, it's the red dwarf stars and their planets. They've emerged as the prime targets in the search for habitable worlds. And the TESS, that's the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, made this discovery in 2023. And according to the authors of the paper in which they published this discovery, it's the first test discovery in the conservative habitable zone. So that's the significance of this particular discovery. And, of course, it was discovered – it's, oh, 137 light years away.

S: Yeah, it's pretty close.

E: Fairly close. Fairly close. And, of course, we discovered it, or TESS uses the transit method to detect. So they saw the dip in the light, and there it was, and they locked it in. Confirmed. Now, the other part of this is that there might be – it's unconfirmed – there might also be a second, smaller planet also detected. in the habitable zone and possibly in the conservative habitable zone. This is TOI-715C, as in Charlie, which is what? The radius size of that planet is 1, 1.066, so that's much closer to Earth's size. And takes about 25 and a half days to go around its red dwarf star. So I imagine that would also tidally lock you.

S: Probably.

E: At that distance. Yeah. So this was actually – the paper was published back in May of 2023. It didn't really make a big splash in the news, but NASA is promoting it this week. Among others, they're propelling it into a major space news story this week. I think what's going to happen is that they're going to turn eventually the James Webb Telescope around. to the planet to get some more details on this. Because it can look at, you know, it looks at the infrared light emitted by exoplanets and it will tell us, you know, is there water? Is there oxygen? Methylene? or perhaps molecules indicating the presence of life. And of course, you know, there's no guarantee that this planet is habitable. You know, it's all going to be, a lot of it's going to come down to the atmosphere, but the fact also that it's tidally locked, that narrows, you know, that makes it less likely.

S: But worse than that, because tidally locked, there could still be a habitable zone around the Terminus. A band. It could be actually pretty big given circulating atmosphere and water and everything. So that's not a deal killer, but the red dwarf is still a semi-deal killer. The thing is, red dwarfs are really active when they're younger, and that would have stripped any atmosphere off of a planet at that distance. So the question is then could it have reconstituted that atmosphere or could it have wandered in from outside the – from farther away after the star had settled down? And again, settled down is a relative term. It's still way more active than our sun is. But if you have like a strong magnetic field and a thick atmosphere – You can't rule out habitability at this point in time for red dwarfs, but it's not looking good, and it's quite possible that red dwarfs are not a good location for Earth-like planets or habitable planets.

B: Unless you consider subsurface habitability.

S: Yeah, but that's not Earth-like.

E: Right. Yeah, it falls into kind of a different category.

B: Right. Yeah, that's just our bias, but it still could be – you could have major ecosystems underground.

S: Yeah, it's one of the ways to rescue that there might be life on that planet. But this is something I've been following it every now and then. I just look. I check the database. I check with NASA and the lists. Are there any planets roughly the size of Earth in the habitable zone of a yellow star?

E: Mid-aged yellow star.

S: Yeah, and the answer is no. Right, not yet. We have not discovered an Earth twin yet. Not yet. With the thousands of exoplanets that we've discovered. But that's partly because the methods that we use are biased towards bigger planets, and they're biased towards planets closer to their parent star. And also, there's a lot of red dwarfs out there.

E: There are.

B: More than any.

S: Yes.

E: And we're also limited to the plane in which we can observe.

S: Yeah, but that should be random, right? That shouldn't bias it in one way or the other.

E: It shouldn't. No. But, you know, there have been over 5,000 confirmed exoplanets. We're north of 5,000 now, which is remarkable. I don't know. When was the first exoplanet confirmed? I don't know.

S: The late 90s, right?

E: Was it late 90s or first suspected detection occurred in 88, but the confirmation came in 1992. Nice. But 5,000 since then. Basically one generation worth of. This sort of space exploration, and we've already gotten to 5,000. We're just at the tip of the iceberg. We'll find it someday, but yeah. The search continues, and of course James Webb is amazing, and it will definitely help in that search.

S: All right. Thanks, Evan. Yep. So, Cara, I understand some scientists want the hurricane scale to go up to 11 or at least 6. Yeah.

Climate Change and Storms (58:32)[edit]

E: 11 might be right.

S: At least 6. Yeah.

C: Yeah, so before I dive into that, this sort of inspiration for my story this week was the horrific storms that we have been dealing with on the west coast of the US. It finally is dry. I'm glad that I have power and internet to be able to record today because a lot of my neighbors do not. There was actually a double atmospheric river situation here in Southern California, actually kind of along the coast, but we got hit super hard in Southern California. I know, Evan, you had said that you have read up quite a bit on atmospheric rivers.

E: A little bit. Well, I don't know about quite a bit, but I've certainly followed the news stories and the phenomenon over the past couple of years because it has become – a very amazing and at the same time deadly phenomenon.

S: Evan, did you know then that an atmospheric river could move twice the water flow as flows through the Amazon River?

E: I did not know that specifically.

B: Over how much time?

E: But I knew it was a lot.

S: If you measure like how much water is moving over a certain distance over time, it's twice as much water is moving through an atmospheric river like what we're seeing in California.

C: Oh, okay. Because I've read that it can be up to 15 times as much water as the Mississippi. But that's like a really bad one. Yeah. A different river. Yeah.

E: Six trillion gallons of water, I heard.

S: It's a lot of water.

C: Yeah. I mean, the numbers are all over the place. There are different ways to measure them. They say on average, there are four or five active atmospheric rivers at any given time going on on Earth. Basically, an atmospheric river is exactly what it sounds like. It's kind of like a river in the sky. It's a section of the Earth's atmosphere that looks river-like. It's narrow and quite long, and it carries moisture from the tropics, so somewhere near the equator up towards the poles. For this storm, it seemed to have been carrying that atmospheric moisture from kind of the Hawaii region towards the west coast. And it dumped over seven inches of rain on Southern California. I think we were looking at, I have a number here, that's the third worst or wettest two-day span in the history of the city, or as long as we've been recording. So the first one was in the 30s, then the 50s. And then we saw this stretch from February 4th to the 5th. And in LA, at least downtown LA, we averaged 7.3, 7.03 inches of rain.

E: According to the San Diego County Weather Authority, the average coastal amount of rain they get in a year is 10 inches for the year.

C: Yeah, this is brutal. Yeah, this is really, really different. And I think in LA, the average is 14 inches of rain. So yeah, in downtown LA, it's 14. So there it's half and in some regions more than half of the average rain for the entire year. And part of the reason that it's so destructive is not because it was a really bad storm per se. Like I was out there, you know, I walk my dog in the rain, no problem. It's that it's sustained. It just sits and dumps and dumps and dumps and it's actually going to rain again today. And even though that's not a storm, it's not really an atmospheric river, the ground is saturated now and all of our watersheds are pretty full. And so there could be some more pretty bad flooding, mudslides, all the things that we see that are happening that cause damage. Billions of dollars in damage and actually several people died in these atmospheric rivers. So that sort of prompted me to want to see, you know, to bring back that conversation about climate change and that conversation about what's different now. You know, atmospheric rivers were only first coined in 94. That could be why... It's been interesting to follow, like Evan, you kind of said, you know, that the news has gotten kind of crazy about them. Well, we didn't, we knew that they existed, but we didn't really have a name for the phenomenon until then. And so, you know, it's a little bit hard to forensically say how much worse are things now than they were, especially when we're still trying to understand the climate. It's so complex. It's stochastic as hell. But we do know a lot. And one of the things that is really interesting to me is a study that was just published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science called The Growing Inadequacy of an Open-Ended Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale in a Warming World. So this was published two days ago as of this recording. And just in case you didn't know, the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is the category scale that we use here in the United States how bad a hurricane is, but really it's not telling us how bad it is because it's not telling us about storm surges. It's not telling us about tornadoes. It's not telling us about flooding or potential loss of life. All it's telling us is what are the sustained winds, which is only one of several different variables that go into the severity of a hurricane. So we are used to this like category one storm, category three, four, five, five, Three, four, and five are considered major storms. As of right now, five is the worst category hurricane that one can be labeled. And that means 157 miles per hour, or that's 252 kilometers per hour or higher of sustained winds. And so at this level, according to NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, that means a high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed. I'm just reading this straight from the website. With total roof failure and wall collapse, fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. And most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks to months. So that's terrible. And this new study does, Basically, the researchers say, we've looked at models, we've looked at observations, and we've collected a lot of data to try and understand if the scale that we're using for sustained wins is actually adequate. And in looking across all of this previous data and modeling for the future, specifically due to the changes that have occurred to hurricane structure and function due to climate change, the researchers here argue that they don't argue for a change to add a sixth category, but they consider, as they word it, we investigate considering the extension to a sixth category of the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale. basically as a means of public science and danger messaging. So here's what they argue is the problem. Category one is from 74 to 95 miles per hour sustained winds. So anything less than that is not a hurricane. Category two, 96 to 110, three, 110 to 129, four, 130 to 156, five, 157 or higher. So anything above that is still a Category 5. But what the researchers argue is that there have been enough examples of what would fall into this kind of arbitrary Category 6 grouping that maybe we should, as a public, as a, you know... the National Hurricane, is that what they're called? The National Hurricane Association Center. The National Hurricane Center, as a group of experts, maybe should start thinking about messaging and considering these things. So their cutoff that they, quote, suggest, I'm trying to be careful with my language here, is 192 miles per hour sustained winds. And they show examples of five or six days different storms, which would have exceeded that hypothetical Category 6 within the last nine to 10 years. Hurricane Patricia in Jalisco, Mexico, which was actually called a Category 4, but they say could be a new Category 6. And then other storms all within the Western Pacific and the Philippines, as well as Taiwan and eastern China. Here's the issue. The higher the wins, the increase exponentially in damage. And so if you have a top, an upper value, and you just say this plus or anything beyond this is category five, it really doesn't communicate to the public how bad it can be. And so that's why they say, is a Category 6 necessary here? Is this something to think about? Because 192 miles per hour is really different from 157 miles per hour. Yeah, big time. We're talking lots more damage, lots more loss of life. That's why they bring this up. They directly link this to climate change. They show pretty convincingly within their paper that this is a new phenomenon. If you look back at the records, historical hurricanes would not qualify as Category 6s. Only new storms seem to be falling within this category.

S: It sounds like we need to update the scale.

C: Yeah. It would be the easiest thing, I think, for messaging. We're all used to the one through five system. And people who live in hurricane zones, they operate with this kind of psychology. Oh, that's just a category three. I should be okay with my hurricane windows. I'll take my patio furniture inside, but I'm not going to board up my windows. Oh, that's going to be a category five. We're probably going to start seeing evacuation notices soon. But I think people... You know, they have, like you were saying before, like institutional, they have kind of human memory for these experiences. And when there's something new that doesn't quite fit the mold, just calling it five could be, I think, detrimental because people may really underestimate how bad it's going to be. Right.

S: It could be an order of magnitude worse than what they're expecting.

C: Yep.

S: Yeah. All right. Thanks, Cara. Yep. All right, Jay. It's Who's That Noisy time.

Who's That Noisy? (1:09:22)[edit]

J: All right, guys. Last week, I played This Noisy. I got a lot of guesses on this one. And, you know, when I heard this noisy for the first time, I actually knew another sound that sounds very, very similar to this, which I will explain to you guys. So a listener named Darcy Stevens wrote in and said, I think this noise is the sound of a high voltage arc from a breaker operation, perhaps a failed operation in a substation where the breaker does not open fully, leading to a prolonged period of arcing, creating the noise. I've actually used that noisy, if I'm thinking correctly. I remember we did one where there was like this massive release of energy.

S: Yeah, it sounds familiar.

J: Yeah, and it does have a little bit of an electrical arc noise to it, but that is not correct. Listener named Shane Hillier wrote in, Jay, this week I think the noise was an A-10 Warthog firing a machine gun. Love the show. Have a great week. So you guys know what an A-10 Warthog is?

S: I'm familiar with it.

C: Is it a plane?

S: It's a pretty

B: wicked military

E: –

J: It's a military craft. It has a unique profile.

S: I think it's like an anti-tank plane, right? It's meant to attack ground forces.

J: I think you're correct, and I think that it's shooting incredibly large rounds. That is not correct.

C: Sorry, Jay. I have to interrupt for a second because I can't. I can't not say this, but I've been watching Masters of the Air, and it's so freaking good. You guys have to watch it.

S: I'm watching it. It's okay. It's no Band of Brothers.

C: It is so good.

S: It's no Band of Brothers.

C: Watch the behind the scenes. Okay. I think it's just because we have such a place in our heart for Band of Brothers, and I've seen Band of Brothers like five times. I think this will compete. We're only three episodes in. Watch the behind the scenes. It's a way bigger production. It was way harder for them to make.

S: Wow.

J: I will look at it. I will do it.

C: It's really interesting. Anyway, go ahead.

J: Next listener, Joey Parker. He said, Love the podcast. I believe the noisy presented in episode 969 is the U.S. Navy Phalanx CIWS close-in weapon system turrets. All right, so I'm looking at a picture of this, the Phalanx CIWS. Oh, it's called CIWS, right? Phalanx CIWS. And my God, this is like a movable firing platform that looks like it has a giant container of rounds. Very, very impressive looking.

C: Is that also on a plane? A turret that goes on a plane?

J: It looks like it's on a boat.

C: Oh, a boat.

J: Pretty sure. Very, very big. Anyway, I haven't heard that. I couldn't find the sound of that. But boy, I get the intensity, right? Just a massive amount of bullets being fired in a short amount of time. Or would you even call them bullets at that point? It's probably a more accurate word for that. But that is not correct. We have a winner and this has never happened before. This is pretty cool. We haven't had winners before. This particular situation happened before. Somebody sent me the correct answer but didn't know that it was this week's Noisy.

S: What do you mean?

E: How did that happen?

J: Meaning that he sent me the noisy of this week.

C: No way. It was like, hey, you should use this.

J: Yeah, and you should use this one. But I'm thinking about it, and I'm like, all right, I didn't have a winner for this week, but this person sent in the correct one. So this person intuitively won the game.

E: All right.

J: That's the way I'm looking at it. Name is Matthew Bornfrund. B-O-R-N-F-R-E-U-N-D. I think I nailed it. So proud.

E: Born true.

J: Hi, Jay. Came across this great video on Instagram. It would be great if they actually took off for a test run, but the sound is fantastic. It is a fantastic sound. Thank you for not knowing that you played and winning. But the answer is this. This noisy was sent in by a listener named Marlo, and Marlo sent in this message. He said, Hi, Jay. This is my new favorite sound. According to the account, this is a pulse jet engine. It's what was on V1 rockets and now on these guys who created the ice buggy, right? These people created an ice buggy that has a pulse jet engine on it. So the jet engine fires a series of super fast pulses of energy instead of it being like one steady stream. I don't know why people would use engines like this. You know, I didn't read enough about it to really understand. Like from a physics perspective, why would you choose to have the engine go blah, blah, blah, blah, blah like that? But anyway, take a listen again now that you know what it is. So it's basically like a jet engine looking type mechanism that is on top of some type of ice buggy sled. Ready? Yeah. I mean, that thing is ramping up. That's one hell of a sound. You can imagine the percussion coming off of that sound, right? If you were within 100 yards of that, you'd feel that for sure. Anyway, cool sound. I have a new noisy for you this week. This noisy, right now, it's my favorite noisy of the year. This is a very, very cool noisy. This is sent in by a listener named Stefan Walker. Try and figure this one out.

S: I love it. I know what you're thinking, Steve. You do? I do. I know what... There's a video game in your mind right now, isn't there? Yeah. Oh, yeah. That's great.

J: It is Portal.

S: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. The turrets.

J: The little turrets that would talk. They'd say funny things after you shoot them over. They'd be like, why did you shoot me? Remember they'd say weird things? Anyway, what a cool noisy. I wasn't going to use it because it's a hard one. It's hard. There's something very particular going on here. But I would love it if you guys could send me in your guesses. You can send a guess or a cool noisy that you heard to WTN at theskepticsguide.org.

New Noisy (1:15:09)[edit]

[Melodic beeping with robotic voice]

J:...There's something very particular going on here...

Announcements (1:16:21)[edit]

...A thousand episodes...

J: Steve, I know I already said it, but we've got extravaganza tickets happening in Dallas. This is April 6th. You could go to the Skeptics Guide website and you can check out the details there. We really hope that you can join us. Tickets are selling fast, but there are seats left and it would be fantastic. Really cool if you could come and hang out with us for a little while. There's also a VIP if you want to get a little extra time with us, and we do give out some swag and whatnot for those people. It's a lot of fun. A couple more things. If you enjoy this show and you want to help a little bit, you can definitely tell a friend. You can definitely leave a review for us on iTunes or whatever your podcast player, if they accept reviews. That's always good. That helps people find us. And if you really want to help us, you could become a patron. You can go to www.patreon.com forward slash skeptics guide. You could join the SGU community. We have an awesome group of people that are on Discord on the SGU dedicated Discord talking every day about all sorts of different things. And, you know, by doing this, you could help support the work that we do and help us continue to doing it. And, you know, look, this is our year where we hit a thousand episodes.

S: Oh, yeah. We have given away a free thousand episodes.

J: It's a lot of work. Yeah. So if you want to show some appreciation for this work that we do, because we really believe in the work that we do, and that's why we've been doing it for 19 years. 19 years ago, I was a completely different person. Right? Think about 19 years ago. I mean, I feel like if you compare that version of me to who I am today, I was like a baby 19 years ago. Aw. Pretty much.

S: Skeptically speaking. Skeptically speaking, yeah.

J: Yeah, that's funny because we really didn't know a goddamn thing about skepticism back then, right? We were doing okay.

E: Since the mid-90s, kind of.

J: We were okay. When we started the podcast, we had a very good understanding. We read a lot of books and everything. But after doing this show for 19 years, my God, we learned so much doing this show.

S: I hope we learned something over that period of time. Yeah.

J: Just so much, though. I mean, I can just see the world in a more refined way than I ever have in my life. And I give it to this podcast for teaching me so much. I learn a lot from you, Steve, and I learn a lot from everybody on the show. And I really appreciate it. I think it's awesome. It's just like the best thing I've done outside of start a family. This is the best thing I've ever done with my life, and I appreciate it.

S: It's the best way to learn is to have to teach something.

J: Definitely. Yeah.

B: It's the seventh best thing I've ever done.

J: And one last thing. My God, do I need my critical thinking skills today more than ever in my entire life? I mean the world is so freaking confusing and full of misinformation. Like Steve and I were just talking about this today on TikTok. Having a skeptical backbone and having those – the ability for those red flags to go up when I detect BS, you know, and it happens every day. Like I really use my critical thinking to my benefit every single day of my life.

B: Yeah, I'm so much more confident when I say these days, oh, yeah.

S: Oh, my God. You say it and give references.

E: That's right.

S: All right. Thank you, Jay.

J: Bye.

Name That Logical Fallacy (1:19:51)[edit]

- "Weaponized pedantry"

S: All right, guys. We're going to do a Name That Logical Fallacy. This is based upon an email sent to us by listener Mike. And Mike writes... Thank you very much. But I have seen people use this reverse gish gallop used all the time. I think a good example of this is when debating anything regarding common sense gun control, a Second Amendment nut will point to the tiniest little mistake in your reference to any firearm and then say something like, since you don't know the difference between a swing arm lever and a coil spring lock on a 1964 or 1911 Smith & Wesson, then you are a moron and can't possibly comment on anything gun related. Just thought if this has never been discussed before, it would be a relevant segment on the show. Thanks, Mike. Yeah, so – Reverse Gish Gallop? Yeah, I don't know that I like that term. I'm not sure exactly how you get that. So the Gish Gallop is a debating technique where you throw out so many claims and misconceptions and whatever that the other side can't possibly deal with them all, right? Because it takes a lot more time to deconstruct and explain why something is wrong.

E: Like a denial of service attack on a website or something.